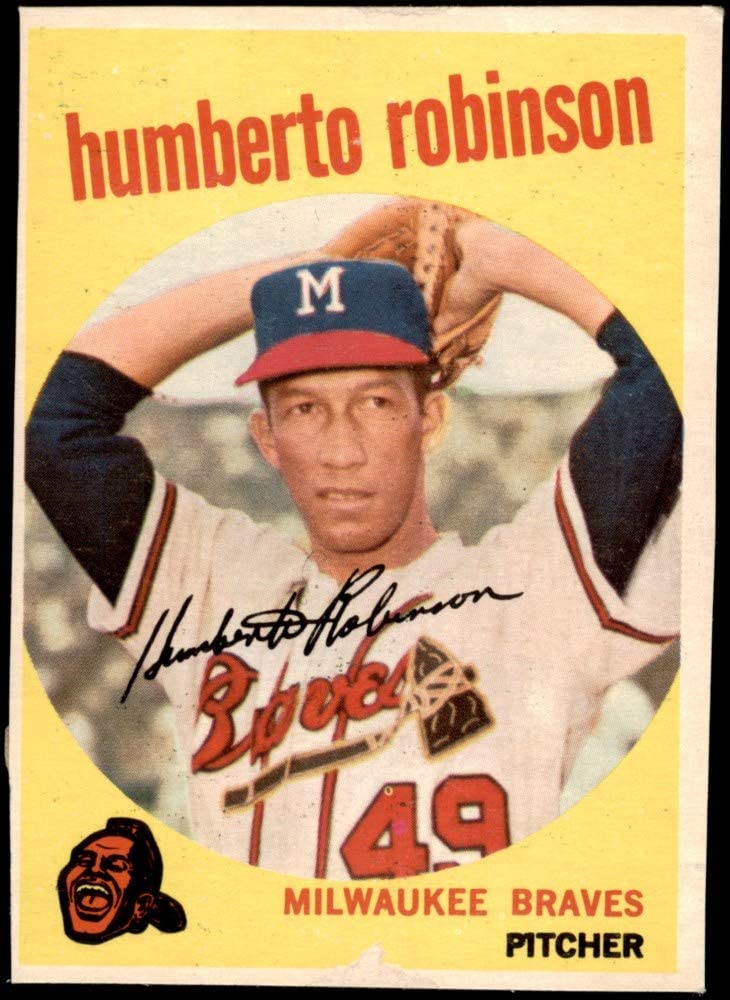

Humberto Robinson

When 25-year-old Humberto Robinson appeared on the mound for the Milwaukee Braves on April 20, 1955, he became the first Panamanian ever to play in the major leagues.1 A quick glance through the statistics he compiled in the majors would indicate the oft-told story of the journeyman just hanging on in the majors for parts of five seasons. Yet, digging in beyond those stats reveals a rich story of triumph over adversity, early career success, a heroic response to a gambling scandal, and finally, an ignominious end to a career that was truly better than it looks on paper.

When 25-year-old Humberto Robinson appeared on the mound for the Milwaukee Braves on April 20, 1955, he became the first Panamanian ever to play in the major leagues.1 A quick glance through the statistics he compiled in the majors would indicate the oft-told story of the journeyman just hanging on in the majors for parts of five seasons. Yet, digging in beyond those stats reveals a rich story of triumph over adversity, early career success, a heroic response to a gambling scandal, and finally, an ignominious end to a career that was truly better than it looks on paper.

Humberto Valentino Robinson was born on June 25, 1929 (some sources claim 1928 or 1930).2 His place of birth was Silver City, Colón Province, near the Panama Canal Zone. Because the Canal Zone was a U.S. territory until the 1970s, the Robinson family is visible in the 1940 U.S. Census. His parents, Tilman and Violet Robinson, were originally from Colombia. Humberto had five brothers and sisters: Hugo, Rafael, Edwardo, Carmen, and Angela. While no records of Humberto’s early youth league experience are presently available, it is likely that he played for the Colón entry in the Panama Major League, an amateur league that was organized in 1945 with teams throughout the country. Panamanian winter baseball began professional play in 1949.

The first solid evidence of Robinson’s professional baseball career dates from The Sporting News in January 1951. He was a member of the Cristobal Mottes, champions of the Canal Zone League, in the winter of 1950-51. He signed with the New York Yankees that year and toiled for the Farnham Pirates in the Class C Canadian Provincial League. In 1952, after another winter pitching in Panama, where he was named to the Panama League All-Star team, Robinson returned to the Provincial League, this time with the Trois Rivières Yankees. The Yanks sold Robinson’s contract to the Braves during the season, and Robinson transferred to the Quebec Braves in the same league, compiling a combined 12-8 record.

After another successful winter in Panama, where he pitched for league champion Chesterfield in the Caribbean Series, the Braves assigned Humberto to their Class B affiliate in Evansville, Indiana. There he enjoyed a stellar campaign, finishing 17-8 with a 2.68 ERA, working mostly as a starter. That earned him a promotion to Class A Jacksonville for the 1954 season, where he dominated the Sally League with a 23-8 record and 2.41 ERA. At the end of the season, he was added to the Braves roster and invited to spring training in 1955.

That spring, Robinson pitched lights-out in training camp, and speculation was strong that he would make the team. Among his admirers was Braves first baseman Joe Adcock, who told Waukesha Daily Freeman sports reporter Tom Guyant that Robinson was one to watch, “If he keeps pitching like that, he’ll stick here sure.” Shortstop Roy Smalley admired Humberto’s curveball, saying, “He was breaking them off to beat the band.”3

Despite his impressive performance, Robinson’s place on the big club was far from assured. With cut-down day looming (in those days rosters were reduced after the start of the season), on April 20 Braves manager Charlie Grimm called the lanky sidewinder in for his first major league appearance to face Chicago Cubs star slugger Hank Sauer, with two outs and the bases loaded in the bottom of the ninth inning. Even though Milwaukee held a four-run lead, the pressure was surely on the rookie right-hander. Robinson whiffed Sauer on six pitches, ending the game, earning his first save, and solidifying his place on the team.4

“Berto,” as his teammates called him, pitched reasonably well in relief for the Braves through April and May, with the exception of one bad outing in a blowout game on May 25 against Cincinnati. He faced the Reds again on May 30, shutting them down on three hits over the final seven innings to earn the win. The next day he was optioned to AAA Toledo, where he spent the rest of the campaign until a September call-up. That September stint was notable for giving Humberto his first major league start, against the Phillies. He responded well, pitching a complete game, 9-1 win. For the season he appeared in 13 games for the Braves, with a 3-1 record, 2 saves, and a respectable 3.08 ERA.

Robinson’s sidewinding style was effective against right-handed hitters, but his control had been spotty (he had walked more batters than he struck out in 1955) and he had not proven to the satisfaction of pitching coach Bucky Walters that he could get left-handers out.5 In 1955, Robinson held righties to a .195 batting average, but lefties swatted .311 against him. He would spend nearly all the 1956 and 1957 seasons trying to improve in those areas in the high minors. He pitched well enough at Wichita in ’56 (9-9, 3.47) and very well in Toronto in ’57, compiling an 18-7 record. However, the Braves had stellar starting pitching, led by Warren Spahn, Lew Burdette, and Bob Buhl, and relievers Don McMahon and Bob Trowbridge were pitching effectively. Robinson could not work his way back to the Milwaukee staff.

Finally, out of options and back in the majors in 1958, Robinson demonstrated improvement in control and in getting left-handed hitters out. In fact, lefties hit only .204 on the season against him. Robinson was used sparingly, however, appearing in only 19 games and logging 41 2/3 innings. In April of that year, he was so frustrated with his lack of use that he publicly asked to be traded. “I’m sick and tired of sitting around,” Robinson told reporters. “And if they can’t use me, why don’t they just send me somewhere else.”6 Bold words from a marginal relief pitcher who had never established himself in the majors. Trade rumors circulated, but since he was out of options, the Braves kept Robinson on the roster; he pitched a few times per month, if that. The Braves went to the World Series that year, losing to the Yankees in seven games. Robinson did not appear; in fact, the Braves used only six pitchers the entire series.

The trade, and with it Robinson’s first extended opportunity to pitch at the top level, came in April 1959, when the Cleveland Indians sent an aging first baseman, former hitting star Mickey Vernon, to Milwaukee for Humberto. Indians general manager Frank Lane said he chose Robinson for his “deceptive sidearm motion and very good curveball.”7

Robinson barely had time to unpack his bags, however, before he was shuttled off to Philadelphia in a trade for Granny Hamner. Thus, he was traded from two first-place teams to a cellar-dweller in little more than a month. Hamner was struggling with a knee injury which made the aging former Whiz Kid available only as a pinch-hitter, and like most teams the Phillies were desperate for pitching. Phils general manager John Quinn said, “Robinson is particularly adept at getting right-handed hitters out and that is important in our ballpark.”8

The 1959 season turned out to be Robinson’s best, and only full, season in the major leagues. Thriving on the regular work he had sought but never received in Milwaukee, Berto ended the season with a combined 36 appearances, 81 2/3 innings pitched, a 3-4 record (including 1-0 with the Indians) and a respectable 3.42 ERA.

The season proved eventful for another reason as well — and that story got Robinson’s name into the newspapers across the country. On September 22, with the Cincinnati Reds in town, the Phillies were scheduled to play a twi-night doubleheader. Both teams were playing out the string on losing seasons. Robinson, who was being used as a starter at the end of the season amid injuries to the Phillies starting staff, was scheduled to pitch the second game.

The night before the game, Robinson was approached by Harold “Boomie” Friedman, in the bar of the Warwick Hotel. Friedman was part-owner of the Moon-glo Supper Club in Philly, a popular, if unsavory, hangout for major league baseball players. “Boomie” was well-known to Robinson. According to a complaint filed in Philadelphia Municipal Court, Friedman offered Robinson $1,500 dollars to “throw” the game. Robinson rejected the offer and later witnesses said that he was visibly upset and crying in the bar after the meeting.

The next morning, Robinson told the court that Friedman appeared in the pitcher’s room in the Rittenhouse Hotel and threw a “down-payment” of 200-300 dollars at Robinson. Robinson again rejected the money, told Friedman to fish it out of the water basin where it had fallen, and asked him to leave.

When he arrived at Connie Mack Stadium, Robinson told fellow Phils pitcher Rubén Gómez about the incident between the games of the doubleheader. Gomez informed their manager, Eddie Sawyer, during the fifth inning of the second game, while Robinson was on the mound. Following the game, Sawyer informed Quinn, who in turn told Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick. Frick passed the information to Philadelphia Police Commissioner, Thomas Gibbon.9

As it turned out, despite his high emotions after the bribe attempt, Robinson went out and pitched one of the best games of his career. He hurled seven innings of three-hit, two-run ball, and was the winning pitcher in the Phils’ 3-2 decision. Just before he took the mound for the game, at the moment he told Gٕómez about the bribe attempt, with his voice shaking, he said, “I am going to win the game.” Then he went out to the mound and did it.10

At the trial, Robinson testified that when Friedman tried to bribe him, he responded, “I can’t do that. I love to play baseball, too much. This is my profession.” Commissioner Frick praised Robinson for his actions, saying he “nipped everything in the bud.” Friedman was eventually sentenced to 2-5 years in prison for his actions. As to why he would attempt to bribe a pitcher on a cellar-dwelling club, who had won only one game the entire season, Friedman never said. His lawyer pointed out the absurdity, but the jury didn’t buy it.11

One more adventure awaited Robinson on the last day of the 1959 season in Milwaukee, when he executed a peculiar “phantom balk.” With Braves pinch runner John DeMerit at third and Eddie Mathews at second, Robinson went into his stretch and then suddenly wheeled and fired to a startled Ed Bouchee at first base. Veteran home plate umpire Jocko Conlan called the balk and waved DeMerit home and Mathews over to third as Robinson could only stand shamefaced on the mound. Afterwards, Conlan said that in his 19 years of umpiring in the big leagues, he had never called a balk like that.

Robinson explained that on the previous play he had rushed to cover the plate when catcher Carl Sawatski muffed a 2-1 pitch. When he got back to the mound, Humberto did not realize that Mathews had moved up from first to second, because his concentration was on DeMerit at third. Nobody on the Phillies infield yelled to tell him and so, unawares, Robinson threw over to an open base. Humberto was still trying to shake off the ignominy of the gaffe the following spring when he told the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Allen Lewis, “I still hear about that one. It was just one of those days I guess.”12

The 1960 season proved to be Humberto’s last in the majors. With the lowly Phils, Robinson compiled a record that would be hard to beat for futility. He pitched in 33 games, of which the Phillies won only one. In that one win on May 31, against the Braves again, Robinson faced two batters, gave up singles to former teammates Hank Aaron and Joe Adcock, and was gone before he could record an out. Overall, Robinson really did not pitch badly, but the Phillies were a very poor team, and pitching almost entirely in relief, Robinson couldn’t catch a break. His last major league outing was on July 24 in Los Angeles, where he pitched two mop-up innings in a 9-0 loss to the Dodgers. On July 30 he was sent down to AAA Buffalo to make room for promising prospect Art Mahaffey. For the season Robinson was 0-4 with a not-bad 3.44 ERA, but the Phillies were moving in another direction.

Robinson pitched for Buffalo through the rest of the 1960 season and in 1961. In 1962, after being cut loose by the Phillies’ Dallas-Fort Worth affiliate, he signed with Veracruz in the Mexican League. As he had done in every season since 1951, he was back in Panama that winter, pitching for his hometown team of Colón. After that he appears to have hung up his spikes for good. There are no further records of him pitching at any level. Despite his mixed success on the major league level, Robinson could point to a gaudy 110-60 record across nine seasons in the minor leagues.

After retirement, Robinson moved to Brooklyn, where he worked in construction for many years. He married Ernestine Frinck in 1989. He died on September 29, 2009, at the age of 80 after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease.13

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the notes cited below, the author referenced baseballreference.com , SABR.org, and retrosheet.org

Notes

1 Baseball Happenings, https://www.baseballhappenings.net/2009/10/humberto-robinson-79-1930-2009-paved.html, retrieved on July 7, 2020.

2 Humberto Robinson Obituary, retrieved from http://www.tributes.com/obituary/show/Humberto-Robinson-86881640. The 1940 census indicates that Humberto was 12 years old, which would mean a birthdate of 1928. Baseball-Reference.com lists 1930.

3 Tom Guyant, “Robinson, Panamanian Hurler, May Furnish Braves with Mound Power,” Waukeesha (Wisconsin) Daily Freeman. March 19, 1955: 11.

4 “Humberto Robinson Wins Place with Braves on Strikeout,” LaCrosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, April 21, 1955: 29.

5 “Braves Uncover Mound Prospect,” Marshfield (Wisconsin) News-Herald, March 16, 1955: 16.

6 “Robinson Wants to Leave Milwaukee. The Capital Times, Madison, Wisconsin, April 22, 1958: 14.

7 “Brodowski Eases Relief Worries; Adds Robinson to Bullpen,” Sandusky (Ohio) Register, April 13, 1959: 12.

8 “Phils Trade Hamner to Indians, Get Reliever Humberto Robinson,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 17, 1959: 97.

9 “Phils Pitcher Charges Bribery Attempt by Café Owner to ‘Fix’ Game”, Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1959: 1.

10 “Phils Pitcher Charges Bribery Attempt by Café Owner to ‘Fix’ Game.” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 25, 1959: 16.

11 “Café Man Convicted in Phillies Bribe,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 30, 1960: 1.

12 Lewis, Allen. “Humberto Wants to Forget His Famous ‘Balk of the Year’,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 20, 1960, 2

13 Panama Cyberspace News, http://panamacybernews.com/team/humberto-robinson, retrieved on July 7, 2020.

Full Name

Humberto Valentino Robinson

Born

June 25, 1930 at Colon, Colon (Panama)

Died

September 29, 2009 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.