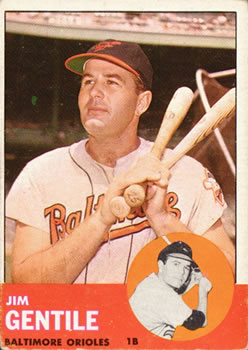

Jim Gentile

The Yankees grabbed all the headlines in 1961. Roger Maris set the new single-season home run record with 61. Mickey Mantle hit 54 home runs himself and was neck and neck with Maris for much of the year. Maris and Mantle finished first and second in the American League MVP voting, respectively, and the team won 109 games, cruising to a World Series championship.

The Yankees grabbed all the headlines in 1961. Roger Maris set the new single-season home run record with 61. Mickey Mantle hit 54 home runs himself and was neck and neck with Maris for much of the year. Maris and Mantle finished first and second in the American League MVP voting, respectively, and the team won 109 games, cruising to a World Series championship.

Yet meanwhile, over in Baltimore, Jim Gentile was making history of his own. The sophomore sensation was overshadowed by the M&M Boys, but he did things at the plate that neither Maris, Mantle, nor anybody else had done before. Gentile hit a grand slam in consecutive innings on May 9 against the Twins, the first time that ever happened. He went on to hit three more grand slams that year, setting an A.L. record and tying the major league record (since surpassed by Don Mattingly and Travis Hafner).

Gentile clubbed 46 home runs and drove in 141 runs. It was in his contract with the Orioles that, if he led the A.L. in RBIs, he would get a $5,000 bonus. Nearly half a century passed until it was discovered that Maris was erroneously given an extra RBI in a July 5 game against the Indians. This reduced Maris from 142 RBIs in 1961 to 141. Thus, in 2010, Gentile received his $5,000 bonus from the Orioles. He ended up being a special guest of the team at Oriole Park at Camden Yards in August of that year. What was about to transpire absolutely shocked him.

“I didn’t know about it,” he said. “They had invited me back to do what we call the suites. You go back there for two days and you go up into the suites and you go around and sign autographs for the people in the suites and so they invited me to do that and while I was there, they said ‘Hey, we’d like you to throw the first ball out,’ and I said ‘Okay.’ So I walk out and a girl walks me out to the mound and I said, ‘Do you have a ball?’ She said, ‘No.’ I see the ball there on the mound and I said, ‘How about this one?’ She said, ‘No, that’s the game ball.’ So, I turned to home plate and I figured the catcher has one. I turned to home plate and there was nobody at home plate. … So here comes Lee MacPhail’s son out with one of those big golf-type checks worth $5,000. That was the first I’d heard of it. I almost fainted, for Pete’s sake.”1

James Edward Gentile (pronounced Jen-TEEL) was born on June 3, 1934 in San Francisco, California. His father was Peter, a truck driver, but Gentile never met him. His mother, Zona, was a secretary at a Chevrolet dealership. She was married four times. Gentile had three siblings, all from different fathers. Thus, his maternal grandmother, Nana Fowlie, raised him and his two sisters, Barbara and Patricia, as well as his brother David.

“My grandmother raised us really well,” he said. “We had a good childhood…anything you wanted, my grandmother was able to give us.”2

No major league teams existed in California when Gentile was growing up. However, there were the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. Gentile not only followed the team but also served as ball boy and bat boy at Seals Stadium on several occasions. “In fact, I was ball boy when Gene Woodling had a great year out there [1948] just before he went to the Yankees,” Gentile said of his future Orioles teammate.3

Gentile originally attended Lincoln High School but as a sophomore, he transferred to Sacred Heart Cathedral Preparatory, where Hall of Famers Harry Heilmann and Joe Cronin also went. As a transfer, he could not play for Dick Murray’s varsity squad at Sacred Heart in 1950. However, as a junior and senior, Gentile, who was both a right fielder and pitcher in high school, helped his school win the 3A City Championships in 1951 and 1952. (They won their fourth straight the following year.)

“Gentile was the best player, but he wasn’t the only one who was really good,” said Ron Gaggero, his teammate at Sacred Heart and a friend of his. “We had a bunch of good players. We didn’t have four or five. We had 10 or 12.”4

Even though Gentile pitched, he saw himself as a thrower and not a pitcher, relying purely on the fastball. He was nervous playing right field during his junior year in high school and didn’t want the ball to be hit to him. He ended up pitching his senior year. Murray was also a scout for the Dodgers, and that factored into Gentile’s decision to sign with Brooklyn. However, he later thought it was the wrong choice.

“I didn’t know about Gil Hodges,” he said with a hearty chuckle. “I didn’t know he was a young man. I didn’t know anything about the big leagues…after I was in their organization for a couple years, I realized that the Dodgers never changed their infield for seven years.” 5

Gentile’s first taste of professional ball was in 1952 as a pitcher with the Santa Barbara Dodgers in the California League. He took a no-hitter late into his debut against the San Jose Red Sox, only to lose the game, 3-2. That season, he went 2-6 with a 3.65 ERA in seven starts.

In 1953, Gentile was converted into a first baseman. He spent the entire season for the Pueblo Dodgers of the Western League. The move paid off. He hit 34 home runs to lead the league and also batted .270 that season.

“When they sent me to Pueblo, they said, ‘You’ll probably only be there for 27 games, and when everybody starts counting down, dropping guys off, you’ll probably go back to the California State League,’” Gentile said. “Well, I started to hit so well, [manager] George Pfister decided to keep me…It didn’t do me any good because I went right back there the next year.” 6

Most of his 1954 season was spent in Pueblo. However, he put in some time at Double-A Mobile. There, he hit eight home runs while batting .233. Gentile spent all of 1955 at Mobile, hitting for higher power and average. Any dreams of a promotion, however, were dashed when he repeated at Double-A in 1956, this time with the Fort Worth Cats of the Texas League.

“When [general manager] Buzzie [Bavasi] called me to tell me he was sending me back to Double-A, I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “I said, ‘What do you want me to do?’ and he said, ‘Well, the Texas League is a much harder league to hit in. All the organizations send their best pitchers there…and the wind always blows over the right field fence in your face.’” 7

Gentile insisted he was not cocky, but he told Bavasi he would hit between 25 and 35 home runs in any place he played. According to Gentile, Bavasi told him he would pay his prospect $100 for every home run he hit past his 25th of the season and $100 for every batting point higher than .300. Gentile batted .296 that season, but he hit 40 home runs, and Bavasi gave him a $1,500 check.

After the 1956 season, Gentile joined the Dodgers on their goodwill tour to Japan. It was during that time he was given a nickname: Diamond. Roy Campanella referred to Gentile as a diamond in the rough. Facing different Japanese teams and stars, he showcased his power with eight home runs, which led the Dodgers. The National League champions went 14-4-1 during their tour.

Gentile said Campanella gave him some advice: “Hey, just hang in there, just wait, you’ll get your shot, and when you do, you got to make the most of it. You’ve got the power, and everybody knows you could hit, it’s just a matter of when you get your shot.” 8

Gentile said he was called up to the majors for one day in 1956, but he did not get to make his debut. For the Montreal Royals in Triple-A in 1957, Gentile hit 24 home runs and drove in 90. He made his first major league plate appearance that season against the Cubs at Wrigley Field on September 10. Facing Dick Drott, Gentile drew a walk which loaded the bases, but all runners were stranded. The Dodgers lost, 9-2.

His first big league hit was a home run on September 22. Gentile connected against his future Baltimore teammate, Robin Roberts, then with the Phillies. The Dodgers won, 7-3.

Two days later, it was Gentile, not Hodges, who was the starting first baseman for the final game ever played at Ebbets Field. The Dodgers beat the Pirates, 2-0.

“To me, it was just great to be able to play the last game,” he said. “I know it meant more to guys like [Duke] Snider and [Pee Wee] Reese who had been there for 10 or 12 years, but to me, it was just another game…It wasn’t that big a thing to me compared to what it must’ve been to the regular pros.” 9

After the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles for the 1958 season, Gentile did get some time with them, but he spent most of the season playing for the Spokane Indians of the Pacific Coast League. Remaining at Triple-A did not sit well with him. “After Montreal, I thought I had a good year, now they’re going to send me to Spokane,” Gentile said. “I didn’t care to play at all. I just kind of lost all interest and I put my hand through a water cooler and took 12 stitches to keep my ring finger on. Just stupid things that year, really bad.” 10

Gentile was in Triple-A yet again in 1959, this time with the St. Paul Saints. He didn’t get any time with the Dodgers, who defeated the White Sox in the World Series. According to Gentile, he was supposed to have been sold to the White Sox in 1959. He said Bavasi called him, told him to pack and that he would be on the flight to Chicago with the team.

“I’m sitting in the lobby with my bags packed, ready to go, and [Saints Manager] Max Macon comes walking through and says ‘Where are you going?’” Gentile said. “‘I’m taking the plane to Chicago,’ and he said ‘No, I just got out of the office with Buzzie and he said that they’re having difficulty on who they’re going to trade you for. So, they want you to work out with me until they get this straightened out.’” 11

The move never happened. In 151 games, Gentile produced. He hit .288 with a .389 on-base percentage with a .512 slugging percentage. He also hit 27 home runs and had 87 RBIs. His numbers in 1959 were better across the board than in Spokane in 1958, but Gentile and Macon never got along.

“One night, when I was at a bar, and he was trying to put the whammy on some girl, she turned him down and came over and had a drink with me, and I think from then on he didn’t like me,” he said. “He even suspended me for the last part of the season…We had just won the game. I went 3-5, drove in two runs. My roommate [Ed] Palmquist pitched. He came in and Mr. Macon had two women sitting above the dugout in Omaha. You can’t help but notice them as you’re coming into the dugout. Well, he comes in and says, ‘Keep your eyes off the women above the dugout, Gentile.’ We got in an argument. So, he suspends me. I go back to St. Paul. I talked to Buzzie, and Buzzie says, ‘The reason that he suspended you is because you came in the clubhouse and picked a fight with Palmquist.’ I told Buzzie, ‘That’s not it at all, Buzzie, but if you want to believe him, he was arguing about the two girls he had sitting above the dugout, and I told him to go poop in his hat.’” 12

Gentile was finally dealt on October 19 of that year. This time, it was to the Orioles and it went through. The Dodgers sent him to Baltimore in exchange for $50,000 and players to be named later (Willy Miranda and career minor-leaguer Bill Lajoie). Yet despite being traded, he was not out of the woods yet.

Gentile had spent the 1959-60 off season in the Panamanian Winter League. Playing for the Marlboro Smokers, he took part in a league championship. He had a multi-homer game on December 22, and hit a grand slam four days later in a 6-5 win. While he was successful down in Panama, that was hardly the case in his first spring training with the Orioles.

Gentile was put on a probationary period. The Orioles had the option to return him to the Dodgers and receive $25,000 back. Manager Paul Richards gave him 120 at-bats once the season started. Richards told Gentile that he couldn’t be as bad as he looked. Richards said he needed power, and if Gentile hit, he would be the first baseman. If not, he would be sent back.

So, hit he did. Gentile started strongly and also drew a lot of walks, and he hit for more power as the year progressed. In total, he smashed 21 homers and drove in 98 in 1960, while hitting .292 and posting a .403 on-base percentage. Gentile was selected to both All-Star teams that season, a feat he would repeat in 1961 and 1962. He went 1-for-2 in the first All-Star game of 1960 at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City. For his efforts, he tied for second, along with teammate Chuck Estrada, for the American League Rookie of the Year vote behind teammate Ron Hansen. The team finished 89-65, second only behind the Yankees in the American League.

“I just think we just had a team that was gelling,” Gentile said. “Estrada was an outstanding pitcher…Ron had a wonderful year…I didn’t even think anything of it until I read in the paper I came in second, but I did have our sports writers come up to me, I had 98 RBIs and they came up and said, ‘Well, we have three games left with Washington’ and he says, ‘If you drive in 100, I’ll vote for you for Rookie of the Year.’ I didn’t play two games. [Jim] Kaat pitched and [Jack] Kralick pitched. I played against [Pedro] Ramos but I didn’t drive in any runs…I would’ve liked to win it, but I didn’t. If anybody had to win it, Ron should’ve won it.” 13

1961 was Gentile’s banner year — but his historic performance on May 9 at Minnesota might not ever have happened. Days prior, Gentile bruised his knee in a game against the Athletics. Still, he took batting practice and felt better.

“I didn’t want to get out [of the lineup],” Gentile said. “I’m there. I finally got a chance of playing in the big leagues, and my mindset was, ‘Geez, if I get out and somebody does good, I could be out of here.’ That’s the way it was. You just didn’t want to get out of the lineup…My knee wasn’t that bad. It was cut up a little bit from running into the wall…but, I knew I could play.” 14

By coincidence, the Twins’ starter that day was Pedro Ramos. In the top of the first with the bases loaded, Gentile cracked his first grand slam of the game. By his account, he was just hoping to drive somebody in because he didn’t want to leave men on base. He was behind in the count, 0-2.

“When you get down to 0-2, now you just want to make contact with the ball,” he said. “The way I swung, it didn’t matter if I had 0-2 or whatever, I swung the same way. He threw me a high fastball and I got up on it.” 15

In the top of the second, against reliever Paul Giel, Gentile launched another grand slam, making him the first player ever to do so in consecutive at-bats. The Orioles wound up winning, 13-5; Gentile (who added a sacrifice fly in the eighth) drove in nine of those runs.

One team Gentile hit exceptionally well in 1961 was the Tigers. On July 1, he clobbered two home runs in an 11-8 loss to Detroit. The very next day, facing Phil Regan in the bottom of the third, Gentile hit his third grand slam of the season, leading Baltimore to a 6-3 win.

Around this time, Gentile was dealing with a jammed thumb. Therefore, he made one plate appearance on July 4 against Cleveland and was out for the two-game series on July 5 and 6 against the Senators. Then came July 7, facing the Athletics. Ed Rakow was on the mound. It was tied at two with the bases loaded in the sixth inning when Richards lifted Marv Breeding for Gentile at Memorial Stadium. Gentile received a thunderous ovation from the hometown fans. He was wearing a golf glove on his left hand and, as a result of his injury, his thumbnail came completely off.

“I used a lot of pine tar, and I got up and the first pitch Ed Rakow threw me was a high fastball and I tried to hold up and the bat went out of my hand … and I got ticked off …so, I just ripped the golf glove off and threw it to the side and got back in there and I guess the adrenaline was flowing because I was mad and the next pitch was a high fastball I hit over the right centerfield fence,” Gentile said of his fourth grand slam. “After I hit it, it hurt like hell, but at the time it didn’t hurt. I guess because I had the adrenaline, I was just so damn mad at the way I almost swung at a ball way over my shoulders and the bat fell out of my hand and I just ripped the glove off and I just jumped back in the box and he just happened to throw the pitch where I could hit it. Then when I rounded the bases, it was stinging like hell.” 16

Gentile’s fourth grand slam put him in elite company. He had become only the seventh player in American League history to hit four grand slams in a year, a list that included Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. Four National Leaguers had reached the mark to that point.17

Gentile’s fifth grand slam of the season came off of Don Larsen of the White Sox on September 22. The only other man who’d hit five in a season at that time was Ernie Banks. It was the sixth and final grand slam of Gentile’s career (he had previously hit one in 1960). Coincidentally, every grand slam he ever hit came in games started by Estrada.

Though he spent just four seasons in Baltimore, the Orioles inducted Gentile into their Hall of Fame in 1989. He played in six All-Star Games, making both teams every year between 1960 and 1962. Gentile specified the first 1961 All-Star Game as the one that stood out to him. It was held on July 11 in his hometown of San Francisco.

“I was the alternate, and Lon Simmons was introducing the players, and he gets to me and he goes, ‘And from the Baltimore Orioles, #4, Don Gentile,’” he said. After he was finished introducing the players, Simmons went to the dugout to apologize. Don Gentile was a flying ace in World War II who popped into Simmons’ mind. “I said, ‘But you watch, you put the hex on me. I’ll have a bad day. Well, Stu Miller struck me out twice and I made an error.’” 18

Paul Richards left the Orioles after 1961 to become the general manager of an expansion team, the Houston Colt .45s. Billy Hitchcock took over for Richards in Baltimore, and Gentile didn’t like it. He said that Hitchcock wanted Gentile to pull the ball more and open his stance. While he didn’t have a problem with Hitchcock as a manager or a person, having to change his stance was not a good fit for him.

“I just couldn’t do it,” he said. “I led the league in home runs in foul territory, but not in fair territory. Even though I hit 33, I was uncomfortable, and so I kept trying it and trying it, and then after the second year, I said, ‘To hell with it, I’m going to go back.’ Now you have to try to find your old stance. Now you have to try to get your muscles to get back to the old way and I just couldn’t get it started again. I changed my stance probably 20 times.” 19

In April 1963, a Sports Illustrated article made the accusation that Gentile and Jackie Brandt could not be bothered to run out ground balls, in addition to the numerous other Orioles who had a problem with Hitchcock and the team’s 77-85 season in 1962. This was a charge Gentile vehemently denied. He said he did a lot of stupid things in his career, but failing to run out ground balls wasn’t one of them.

“If you didn’t run ground balls out, they fined you, so how can that happen?” Gentile asked. “Paul Richards would fine you $25 if you didn’t run a ball out. I never had any trouble. The only time I had trouble with Hitchcock — we were in New York and [Al] Downing’s pitching, he throws me a fastball inside, I tried to get out of the way and it hits my bat. It’s rolling foul. I take about 10 steps and it looks like it’s going to stay foul, and I don’t know what it hits, but it bounces back fair and they tagged the base and I’m out, and Hitchcock [said] — ‘$25.00’. I got fined. He said, ‘You didn’t run it out.’ I’ll go to my grave saying I never didn’t run a ball out.” 20

Gentile’s 1963 season was his last in Baltimore. He continued to display his power, hitting 24 home runs with 72 RBIs in 145 games, but his average fell off to .248. The team went 84-78, an improvement over 1962. Following the season, he was shipped to the Athletics with $25,000 for Norm Siebern. The Sporting News described the swap as “hitting consistency, speed and hustle [Siebern] for defense, power and color [Gentile].” Gentile was also described as “entertaining” and “fiery.” 21 It’s noteworthy that his fielding was mentioned — he was also well respected in that area — but one may also infer that the bad rap he’d gotten about running balls out was still hanging over him.

In an effort to get more pop out of the lineup, Kansas City also acquired Rocky Colavito from Detroit. In his one and only season with the Athletics, Colavito was an All-Star with 34 home runs and 102 knocked in. Gentile also brought power, driving in 71 with 28 home runs. They had a great relationship and were roommates during the season.

“I used to get on him, I would say, ‘Will you leave somebody on base for me?’” Gentile said. “I would hit after Rocky and Rocky wouldn’t leave anybody on base.”22

Speaking of home runs, Kansas City’s pitchers gave up a lot of them. That was a big reason why, despite the power coming from Colavito and Gentile, the Athletics went 57-105 in 1964.

“Back then, [owner Charlie] Finley wanted to run everything,” Gentile said. “He’d listen to games on the phone, and if he didn’t like what was going on, he’d call the dugout. Eddie Lopat was a great, great manager. He was a players’ manager and [Mel] McGaha came and he didn’t do very well, so he got rid of him and brought in [Haywood] Sullivan. When Rocky left, he left it up to me for the long ball, as Finley would say. When he traded me [in June 1965], Mickey Mantle and I were leading the league in home runs with 10 and that’s when he traded me to Houston.” 23

Gentile hit just seven homers for Houston over the remainder of 1965 — none in the cavernous Astrodome, a notorious pitchers’ park. He spent his final season in the majors, 1966, splitting time between the Astros and Indians. He was traded because Grady Hatton, in his first season as manager of the Astros, didn’t really want Gentile. On July 19, the Astros got Tony Curry and cash from Cleveland. Gentile had been demoted to Oklahoma City after smashing his bat and flipping it at umpire Ed Vargo, who’d called him out on strikes.24

“Temper” was a word frequently associated with Gentile, who described himself as “just a hard-boiled paesano.”25 A mellowed Gentile later reflected, “I decided my temper was not good for me when I got busted [for the Vargo incident]. It about ended my career. That day, I sat alone in the clubhouse after everyone left and realized I was my own worst enemy.” He credited his wife, Paula, for teaching him to laugh at himself. “It doesn’t help if you have a bad attitude,” he said. “You’ve always got tomorrow.”26

Gentile’s last major-league appearance came on September 30, flying out to center field against Dean Chance and the Angels. He still spent the rest of the 1960s in professional baseball, though. He was with the San Diego Padres, then the Triple-A affiliate of the Phillies, in 1967 and ’68. Though he did go to spring training with them, he never appeared in a major- league game in Philadelphia.

Gentile finished his playing career in Japan for the Osaka Kintetsu Buffaloes in 1969. The Buffaloes offered Gentile $25,000, whereas the Phillies organization was paying him merely $10,000. Manager Gene Mauch had decided to keep an extra pitcher on the roster over Gentile, and he couldn’t stay on the roster even though regular first baseman Bill White was out of commission during spring training. Gentile asked for and was granted his release from the Phillies to go to Japan — but he had to pay $5,000 in order to receive it.

On Opening Day in Japan, Gentile ruptured his Achilles tendon and was out for two months. In 65 games with Kintetsu, he hit eight home runs and had 16 RBIs. He was not able to adjust to Japanese baseball and wasn’t brought back. That was the end of the line for his playing days.

“After I left baseball, that was my biggest thing, ‘What am I going to do?’” Gentile asked. “I went to work for a tire company, Globe. I worked for them, learned the tire business. I got a Midas muffler franchise, did that for a couple of years. I sold that, came to Oklahoma. I worked for a company here, a tire company and I got five years in managing independent baseball.” 27

Gentile managed the Fort Worth Cats (2001-02) and Mid-Missouri Mavericks (2004-05.) His most notable managerial season came in 2001 when he guided the Cats to a 37-35 record and the first round of the playoffs.

“I was in a learning process myself,” he asked. “I just told them, ‘We’re going to hustle, we’re going to give 100% every game. The first year there, we should’ve won the playoffs, but a couple of my pitchers, one guy thought he was Mr. Whitey Ford, didn’t cover first base, and we lost 3-2 to knock us out. I just tried to instill to play hard. I yanked pitchers pretty fast, I guess. If it looks like he was running out of gas, I got him out of there as quick as I could. But I enjoyed it.”28

Gentile later became the hitting coach for the now-defunct Schaumburg Flyers. After coaching, he ran his own baseball camp in Chandler, Oklahoma. Now retired, he lives in Edmond, Oklahoma. Gentile had previously lived in Tempe, Arizona from 1971-79 before moving to Edmond. He has four sons (Steve, Scott, Bo, and Tony) and one daughter (Tori). Some of his children came from his first marriage to Carol Housman. He has been married for 50 years to his current wife, Paula (née Nance), an Oklahoma native whom he met when she was working as a flight attendant for Braniff Airlines.29 He has two grandsons, Tre’ and Braden, as well as a granddaughter, Nikki, who currently serves as the softball head coach for Solano College.

“My grandpa is so sweet to me,” Nikki Gentile said of Jim. “He would get to see me play at times. He would drive down to Texas…he drove up to Iowa to watch me play. He was always a part of it. He’ll still talk ball with me, swings, techniques and all of that. I would always take his advice. I’m proud to be associated with him. He’s such a great role model and he’s always so proud of me.”30

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Telephone interviews (all with the author)

Grateful acknowledgement to the following for their memories:

Jim Gentile (May 13, 2017)

Ron Gaggero (May 12, 2017)

Nikki Gentile (May 2017)

Books

Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana: The History of Cuban Baseball, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lou Hernández, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947-1961: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011.

Robert K. Fitts, Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game, Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Articles

“Baltimore Orioles: The Bright Young Men Must Come of Age,” Sports Illustrated, April 8, 1963, 77.

Doug Brown, “Gentile’s Slams Loaded with Memories,” Baltimore Sun, May 25, 1995.

Doug Brown, “Hats Off! Jim Gentile,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1961, 15.

Mike Klingaman, “Catching Up with…ex-Oriole Jim Gentile,” Baltimore Sun, June 2, 2009.

Websites

Baseball-Almanac.com

ClassicMinnesotaTwins.blogspot.com

HardballTimes.com

JonFinkel.com

UrbanShocker.wordpress.com

WalterOMalley.com

Notes

1 Phone interview with Jim Gentile, May 13, 2017 (hereafter Gentile interview).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Phone interview with Ron Gaggero, May 12, 2017

5 Gentile interview.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 For the list of single-season leaders in grand slams, see http://www.baseball-almanac.com/hitting/higs2.shtml.

18 Gentile interview.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid.

21 Doug Brown, “Orioles Expect Siebern to Add Hustle, Spark,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1963, 65.

22 Gentile interview.

23 Ibid.

24 John Wilson, “Bat-Tosser Gentile Headed for Minors, Fights Back Tears,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1866, 6.

25 Allen Lewis, “Phillies Add Briggs and Kuenn to Field for Gateway Derby,” The Sporting News, January 21, 1967. Murray Olderman, “Hot-Tempered Oriole,” The Saturday Evening Post, 1961, August 26, 1961, 21.

26 Kathryn Spurgeon, “’Diamond Jim’ Gentile,” Edmond Outlook, August 2006.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Tom Kensler, “A Couple of Blasts from the Past,” The Oklahoman, September 8, 1987. Spurgeon, “’Diamond Jim’ Gentile.”

30 Phone interview with Nikki Gentile, May 2017.

Full Name

James Edward Gentile

Born

June 3, 1934 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.