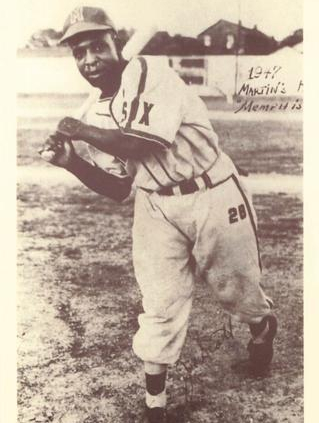

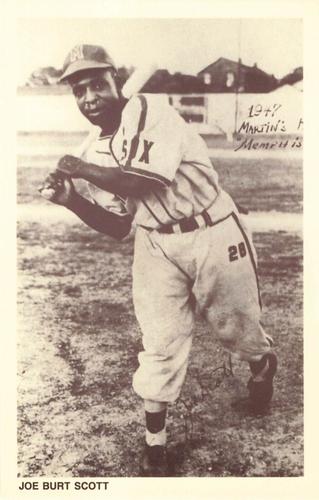

Joe Burt Scott

Joe Burt Scott’s professional baseball career intersected with the emerging opportunities in the sport following Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the waning years of the Negro Leagues. This left-handed first baseman and outfielder was 26 years old in 1947, when he hit .400 for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League. In spring 1948, he studied at the Rogers Hornsby baseball school in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Scott hoped that placed him at the front of Negro Leaguers sought by Organized Baseball.1

Joe Burt Scott’s professional baseball career intersected with the emerging opportunities in the sport following Jackie Robinson’s 1947 debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the waning years of the Negro Leagues. This left-handed first baseman and outfielder was 26 years old in 1947, when he hit .400 for the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League. In spring 1948, he studied at the Rogers Hornsby baseball school in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Scott hoped that placed him at the front of Negro Leaguers sought by Organized Baseball.1

Unfortunately, Scott was caught in the monetary dispute between the two entities, and his career remained on the periphery of professional baseball. His action included stints during World War II with base teams playing against barnstorming squads featuring Dizzy Dean and Satchel Paige. The heart of his career found Scott playing for the Memphis Red Sox. Scott never appeared in an East-West All-Star Game or on a major-league roster – at least until the Negro Leagues were retroactively recognized as such in 2020 – yet his role as an ambassador of those leagues in later life endeared him to many.

Joe Burt Scott was the second of Charley Scott and Lucy Payne Scott’s four children. He was born on October 2, 1920, in Memphis, Tennessee. When Scott turned 10, his father, a mechanic by trade, left the family to pursue success with a cousin.2 Lucy became a single parent, working as a maid to support Joe, his older brother Charles (born in 1918), and his younger sisters Irma (1922) and Naomi (1923).3 In 1935, she and the four children moved to Chicago, Illinois. There she married William Gallaway and gave birth to a fifth child, Edith (1936).4

Scott grew up in the Bronzeville section of Chicago on Forty-sixth Street. Like many other African-American families of the period, the Scotts had relocated to Chicago hoping for a better life and less racial oppression. Bronzeville’s residents toiled hard and cooperatively to establish a full-fledged community with business and cultural institutions. These grew to have national influence, rivaling New York’s Harlem in social fabric.5

Growing up in Chicago, Scott was a fan of Joe Lillard, a football player formerly with the Chicago Cardinals. Lillard was among the last two African-Americans allowed to play in the NFL before the “gentlemen’s agreement” amongst NFL owners to keep Blacks out of the NFL from 1934 to 1945.6 Scott knew of Lillard’s prowess; The Chicago Defender had described him as “easily the best halfback in football.”7 The story of Lillard’s blacklisting taught the young Scott that flashy play by black athletes led to perceptions of cockiness by white teammates and eventual exclusion.

Scott attended Tilden Tech High School, within walking distance of his Forty-sixth Street house. He began his athletic career at Tilden as part of the “sophomore” (i.e., junior varsity) football team. In the spring, he turned his attention to the diamond, where he earned a varsity baseball roster spot as a freshman. Although 20 percent of Tilden Tech’s students were black, he was the squad’s only black player. Under Coach Shortall, the Craftsmen won the City Championship at Wrigley Field by defeating Schurz High, 8-5.8 This game became one of Scott’s early career highlights, as he was the only black player on the field that day.

Scott played baseball all four years at Tilden and served as a co-captain during his senior year.9 Playing baseball in an integrated school proved important in how he viewed race and sport. Scott said, “All I was thinking about was baseball and playing. That’s all. It wasn’t. It didn’t make no difference.”10 This mantra would serve him well throughout his career.

After graduation from Tilden Tech, Scott got a job loading beef onto boxcars, allowing him to play baseball in the Chicago industrial league. While playing in that circuit, Scott garnered an opportunity to play with one of Satchel Paige’s barnstorming teams.11 In a 1994 interview, Scott recalled his first hit off Satchel while playing with one of Dizzy Dean’s barnstorming teams in Dayton, Ohio. “He struck me out the first time. Dizzy was hitting in front of me, so he walked Dizzy to pitch to me and said, ‘C’mon kid, get ready for this fire.’ I tripled against the left-center field fence. When I got to third, Satchel came over and said, ‘What did you hit, kid?’ I said, ‘That fire!’”12 While barnstorming, he lived with his mother and stepfather in Bronzeville.

Following the bombing of Pearl Harbor at the end of 1941, Scott reported to the draft office in Chicago in February 1942 and enlisted in the U.S. Army. During World War II, Scott spent his years playing on Army baseball teams at Wright Airfield in Dayton, Ohio (the Kitty Hawks), and the Great Lakes team in Michigan.13 Frequently, Scott took three-day passes from his commanding officer at Wright and picked up with barnstorming teams. While playing a game in Belleville, Illinois, a lieutenant from the Wright Airfield base team approached Scott and offered him the opportunity to leave his all-Black unit and join the post’s baseball team as part of the Special Services.14

While he was stationed at Wright Airfield, the New York Black Yankees signed Scott for $500 upon his release from the service.15 Then, during the 1945 Negro American League season, the Memphis Red Sox visited Chicago’s Comiskey Park to play the Chicago American Giants. Still serving in the Army in 1945, Scott got a call from Verdell Mathis to meet the team in Chicago. Red Sox general manager B.B. Martin wanted to see the young Scott hit. Inserted in the game in the early innings by manager Larry Brown, Scott doubled.16 Scott’s pinch hit in Chicago for the Red Sox foreshadowed the best years of his playing career in Memphis.

Following his release from the Army, Scott reported to New York to play for manager Marvin Barker’s 1946 Black Yankees. Making only $500 a month in New York, Scott jumped teams midway through the summer and joined Gus Greenlee’s Pittsburgh Crawfords, who paid him $750 a month.17 Scott helped the Crawfords secure the United States League championship in 1946. The USL, an attempt by Greenlee to create a circuit that rivaled the Negro American League and Negro National League, was short-lived, providing Scott with only a short stay in Steel City.18 Scott returned to Memphis to play for the Red Sox in 1947. He patrolled the outfield while hitting .400.19 The smooth-hitting lefty became one of the team’s most feared batters. Statistically, the 1947 season was the best of his career.

Scott returned for the 1948 NAL season as part of Larry Brown’s opening-day lineup.20 Scott dazzled fans at Martin Stadium by racing to the left field wall and making a one-handed grab. In the bottom half of the inning, he showcased his speed by stealing second, third, and home. The Red Sox defeated the Atlanta Black Crackers, 10-4.21

During that season, Scott’s career became part of the tug-of-war between Organized Baseball and the Negro Leagues. Rogers Hornsby recommended Scott to the Poughkeepsie Chiefs of the Class B Colonial League after Scott attended his diamond school in Hot Springs in the spring of 1948, the first African American to participate in the program.22 Scott hoped, like many of his Memphis teammates, that after the Brooklyn Dodgers’ signing of Red Sox pitcher Dan Bankhead in 1947, they too would get an opportunity to play in Organized Baseball. Poughkeepsie offered the Red Sox $5,000 for his contract. However, W.S. Martin and B.B. Martin, the Memphis owners, would not sell it for anything less than $15,000. Scott personally protested the Martins’ denial of Poughkeepsie’s $5,000 bid. He told the Martins, “I didn’t cost you, not even one red penny. I’d like to go up there.”23 Unfortunately, the Martins never budged, and Scott lost an opportunity.

As Organized Baseball clubs added Black players to their rosters, the Negro Leagues continued to market themselves in unique ways to bring fans to the stadium. For example, the Red Sox marketed Scott’s speed between games of a July doubleheader with the Cleveland Buckeyes by having him race teammate Bob Boyd and Buckeyes players Sam Jethroe, Archie Ware, and Al Smith in the 100- and 220-yard dashes.24

As of early August, Scott continued to swing a hot bat for the Red Sox and joined four other teammates hitting over .300 heading into a weekend series against the Buckeyes.25 Unable to convince the Martins to sell his contract to Poughkeepsie, Scott completed the 1948 season with a .292 batting average for the Red Sox.26

Scott returned to the Red Sox for the 1949 season under manager Goose Curry. In an early-season game with the New York Cubans, he rapped out four hits to secure the Red Sox’s 7-3 victory.27 As Scott remained in Memphis, George Handy, his former Red Sox teammate, joined the Bridgeport Bees of the Class B Colonial League, where he hit .346 with 22 home runs and 25 stolen bases in 126 games.28 Negro Leagues historian Jules Tygiel argues that despite rumors of the imminent signing of Black players, as of July 17, 1947, only the Dodgers, Cleveland Indians, and St. Louis Browns had taken the fateful step at the top level.29 Many Black players who did sign were left scuffling through the minor leagues. Others, like Scott, patiently waited for the minors to offer them the same opportunity. When Handy returned to Martin Stadium for an October exhibition against an all-star team, Scott’s reality struck home.30

In an issue unique to the Negro Leagues during the 1949 season, W.S. Martin kept Scott on the roster without having him physically sign a new contract. Refusing to give Scott a raise, Martin played Scott in 1949 under his 1948 contract. Unable to get what he considered a fair deal, Scott – as did many other Black players of the day – went north to play in Canada’s Provincial League in 1950. W.S. Martin sought compensation for the loss of Scott and contacted George Trautman, the president of minor league baseball. When Trautman discovered that Scott had not signed a contract for the 1949 season, Trautman told Scott that Martin had no legal ground to stand on; he was free to play in Canada.31

Scott played well for the Farnham Pirates in 1950, as he posted a .312 batting average, but he joined another Provincial League club in 1951: the St. Hyacinthe Saints. When his batting average fell below .300 in the Class C minor league, he returned to Memphis.32 Scott was out of baseball for the next two years.

In 1954 the Hot Springs Bathers of the Class C Cotton States League picked up Scott for a brief two-game stint. A year earlier, the Bathers had signed Jim and Leander Tugerson, brothers who pitched for the Indianapolis Clowns, to become the first two African Americans to play in the Cotton States League. The league expelled the Bathers, and they were reinstated only upon appeal to Trautman. Trautman’s decision stated that “the right to employ any player, regardless of ‘race’, ‘color’, or ‘creed’, lay with the individual club.”33 When Charlie Williamson, the Bathers’ owner, brought Scott to Hot Springs in 1954, this was no longer a strike at segregation but a marketing ploy to boost sagging attendance. An Arkansas paper, the Hope Star, reminded its readers that only one year earlier, the owners of the Cotton States League “bitterly opposed the use of Negroes.”34

Scott eked out two singles in his 10 plate appearances for the Bathers and returned home to Memphis.35

Two years later, Scott’s last opportunity in professional baseball came with the Knoxville Smokies of the Class A South Atlantic League. Dick Bartell offered Scott a chance on a 10-day contract. In his first game, he “got a Texas-leaguer to left” to score a run in the bottom of the fifth.36 Scott saw action, but the racial animus that followed signaled it was time for him to retire. Whenever he came to bat, the fans chanted, “Strike that nigger out!” After two games of the same treatment, Scott went to Bartell and told him he was returning to Memphis to get a job.37

Jules Tygiel reminds us that fan hostility further complicated the Black athlete’s life. Hometown spectators rarely posed a problem, but Southern fans unleashed an unending string of racial invective against visiting players.38 For Scott, his last two opportunities in Organized Baseball were publicity stunts, a chance for minor-league franchises to offer their fans the oddity of seeing a Black player. Marketing schemes to boost attendance only exacerbated the challenge facing Negro Leaguers like Scott trying to continue their careers.

Scott’s legacy went beyond his playing days, as he became a mentor and an ambassador for baseball in Memphis. A local man named Angelo Luchesi remembered Scott sharing the tricks of the trade with him as a kid in the 1970s. First, Scott taught him how to read the ball off the bat while playing in center field. Then, Scott suggested that Luchesi, a fellow lefty, start taking the ball the other way to the left-center gap to increase his slugging percentage.39 Luchesi was one of many Bluff City youngsters with whom Scott shared his love of the game.

Later in life, Scott became an ambassador for Negro Leagues baseball. As a result, when Major League Baseball held a special honorary draft for former Negro Leaguers in 2008, the Milwaukee Brewers selected Scott.40 He and fellow survivors thus represented the many Black players who did not have the opportunity to play in the National or American Leagues.

Autozone Park in Memphis, home of the St. Louis Cardinals’ AAA affiliate, offered the opportunity to continue to share the story of the Memphis Red Sox and Negro Leagues baseball. In July 2008, the Redbirds hosted Scott and fellow Red Sox players Ollie Brantley, Lonnie Harris and James Woods, for “Conversations with History: Memories of the Negro Leagues.” Through events like these, Scott kept the memory of the Negro Leagues alive in his hometown. As a result, Redbirds GM David Chase welcomed Scott to Autozone by giving him a lifetime pass to games and saluting the Negro Leagues yearly when the Redbirds annually donned Memphis Red Sox uniforms.41

Joe Burt Scott died in Memphis on March 21, 2013. He was 92. He never married or had children. Following his death, the city’s leading newspaper, The Commercial Appeal, reminded its readers that Scott “was respected and admired by baseball aficionados for his accomplishments on the baseball diamond and his work promoting the sport among Greater Memphis youngsters. He was blessed to have his accomplishments recognized during his lifetime. And the city was blessed to have him use that recognition to be a great ambassador for baseball.”42 Scott is buried in the West Tennessee State Veterans Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee.43

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Mike Eisenbath and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Photo credit: Joe Burt Scott, Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the noted, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Seamheads.com, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, and the Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research website.

Notes

1 “Red Sox top Georgians.” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), March 22, 1948:19.

2 Jim Burgess, “Joe B. Scott Biography,” Baseball in Living Color. Accessed January 1, 2023. https://www.baseballinlivingcolor.com/html2014/player.php?card=147.

3 15th US Census (1930).

4 Joe Burt Scott, interview by Curt Hart, March 2008.

5 Bob Glaze, “Exploring the Historic Bronzeville Neighborhood in Chicago,” Classic Chicago Magazine, August 15, 2021. https://classicchicagomagazine.com/exploring-the-historic-bronzeville-neighborhood-in-chicago/#:~:text=Bronzeville%20is%20an%20historic%20neighborhood%20on%20Chicago%E2%80%99s%20South,as%20an%20early-20th-century%20African-American%20business%20and%20cultural%20hub.

6 John Eisenberg, The League: How Five Rivals Created the NFL and Launched a Sports Empire, New York: Basic Books (2018): 103.

7 Thomas G. Smith, “Outside the Pale: The Exclusion of Blacks from the NFL, 1934-1946,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 15, No. 3, (Winter 1988): 257.

8 Burgess, “Joe B. Scott Biography.”

9 “Tilden Technical HS 1937 Yearbook,” E-Yearbook.com. Accessed December 29, 2022. http://www.e-yearbook.com/sp/eybb. “Joe B. Scott,” Negro Leagues baseball emuseum. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://nlbemuseum.com/history/players/scottj.html.

10 Joe Burt Scott, video interview by Steven Ross, April 1994. Video #4. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee (hereafter Scott-Ross interview).

11 Burgess, “Joe B. Scott Biography.”

12 Scott-Ross interview.

13 Gary Bedingfield, “Negro Leaguers Who Served in the Armed Forces in WWII,” Baseball in Wartime. Accessed December 27, 2022. https://www.baseballinwartime.com/negro.htm.

14 Marlin Carter, Verdell Mathis, Frank Pearson, & Joe Burt Scott, video interview by Steven Ross, April 1994. Video #4. Special Collections, Ned McWherter Library, University of Memphis, Memphis, Tennessee.

15 Phil Dixon, The Negro Baseball Leagues: A Photographic History, (Mattituck, New York: Amereon House, 1992), 293.

16 Scott-Ross interview.

17 Dixon: 293.

18 Rob Ruck, Sandlot Season: Sport in Black Pittsburgh, Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press (1987): 175.

19 Seamheads Negro Leagues Database.

20 “Red Sox open season,” Commercial Appeal, March 21, 1948: sect. II, 10.

21 “Red Sox tops Georgians,” Commercial Appeal, March 22, 1948: 19.

22 “Poughkeepsie seeks Negro Red Sox star,” Commercial Appeal, April 15, 1948: 31.

23 Scott-Ross interview.

24 “Red Sox play Buckeyes,” Commercial Appeal, July 11, 1948: sect. II, 6.

25 “Red Sox meet Buckeyes,” Commercial Appeal, August 1, 1948: sect. II, 3.

26 “Joe Scott will start,” Commercial Appeal, April 2, 1949: 19.

27 See note 25.

28 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers (1994): 352.

29 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy, New York: Oxford University Press (1983): 224.

30 “Handy to be in lineup,” Commercial Appeal, October 6, 1949: 35.

31 Scott-Ross interview.

32 “Joseph B. Scott Minor League Statistics.” Stats Crew, Accessed December 31, 2022. https://www.statscrew.com/minorbaseball/stats/p-064b01d7. The website correctly identifies Joe Burt. Scott as the player, but it inaccurately lists his birthdate and place of birth. If you cross reference Joe B. Scott with Joe Scott (Joseph B. Scott), who played for the Birmingham Black Barons, the website lists Joseph B. Scott’s birthplace and birthdate in lieu of Joe Burt Scott’s. Joseph B. Scott played in Chicago with the CAG in 1950, and then returned to Los Angeles, California, where he worked on the railroad for the next 28 years (per the SABR Bio-Project).

33 Tygiel: 274.

34 Yale Talbot, “Spa Owner Solves Attendance Problem,” Hope Star. (Hope, Arkansas) September 1, 1954: 13.

35 “Joe B. Scott Minor League Statistics.” Stats Crew. Accessed December 31, 2022.

36 Frank Bailes, “Smokies purchase Negro outfielder,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, July 4, 1956: 20.

37 Scott-Ross interview.

38 Tygiel: 282.

39 Angelo Luchesi, interview by author. December 30, 2022.

40 “Negro Leagues Player Draft 2008,” The Baseball Sociologist, May 12, 2017, https://baseballsociologist.wordpress.com/2017/06/05/negro-leagues-player-draft-june-5-2008/.

41 “Redbirds to Honor Negro Leagues,” OurSports Central, July 9, 2008. https://www.oursportscentral.com/services/releases/redbirds-to-honor-negro-leagues/n-3677782.

42 “Baseball’s Joe B. Scott,” Commercial Appeal, March 23, 2013: 6A.

43 “Sgt Joseph Burt ‘Joe’ Scott ,” Find a Grave, accessed March 29, 2024, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/107746692/joseph_burt-scott.

Full Name

Joseph Burt Scott

Born

October 2, 1920 at Memphis, TN (USA)

Died

March 22, 2013 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.