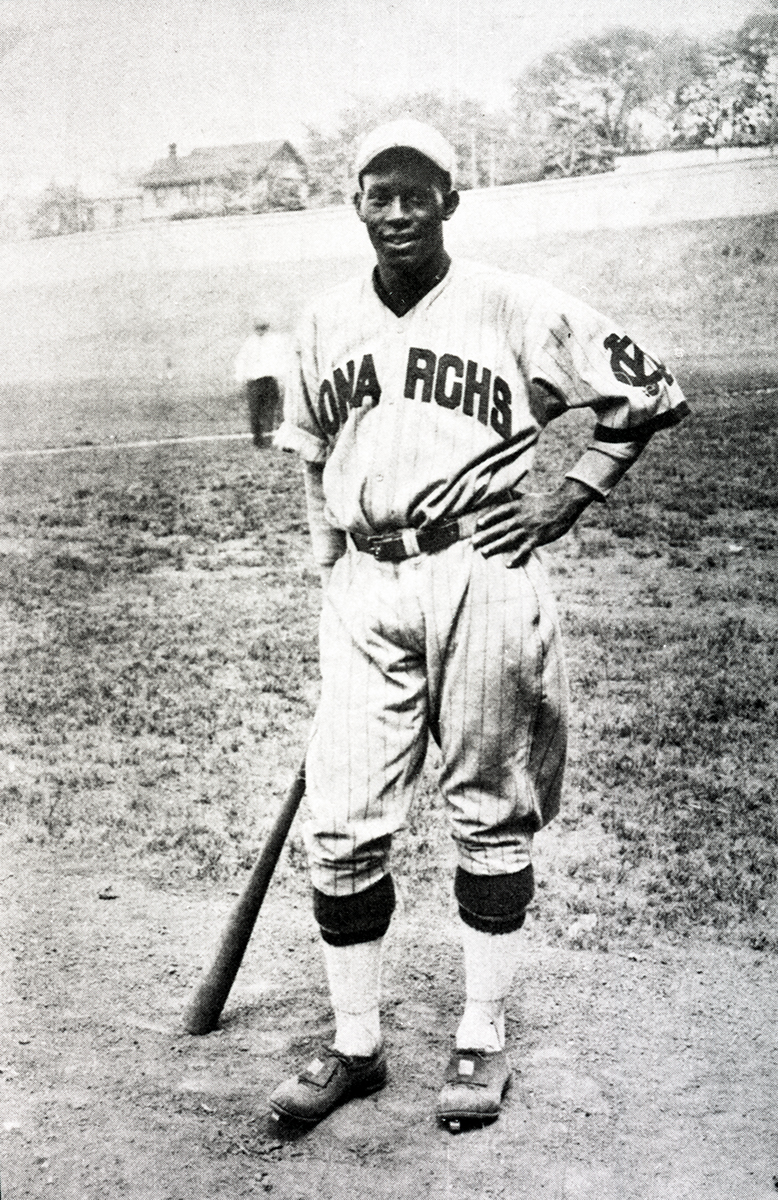

Newt Allen

Second baseman Newt Allen’s Kansas City Monarchs teammates gave him the nickname “Colt” in 1922 because he was the youngest member of the team.1 Over the course of a 23-plus-year career in the Negro Leagues that also included stints in other countries, Allen proved to be one of the best players ever to man the keystone sack. During his tenure with the Monarchs, Allen contributed sterling defense and a potent bat to 11 championship squads.2

At the conclusion of his second full season with Kansas City, he played in the first Negro League World Series, in which the Monarchs defeated the Hilldale Club of the Eastern Colored League. Eighteen years later, now a seasoned veteran, he helped the Monarchs triumph over the Negro National League’s Homestead Grays in the first Negro League World Series between those two circuits. During the intervening years, Colt Allen had galloped over all competition so soundly that in 2006 he was on the final ballot of the Special Committee on the Negro Leagues for induction into the Hall of Fame, though he ultimately fell short of enshrinement.

Newton Henry Allen was born on May 19, 1901, in Austin, Texas, to Newton H. and Rose (Baker) Allen. The elder Newton and Rose had married in 1897 and led a hardscrabble existence as they raised a family in Texas’s capital city. Newton Allen was a laborer who worked whatever odd jobs he could find while Rose worked as a laundress. Young Newt had an older sister, Dora, and was joined later by another sister, Eva Mae, and a brother, Lawrence; two other siblings, including a sister named Mary who was born in 1903, died in childhood prior to 1910.

Newt’s father succumbed to tuberculosis on July 21, 1910, forcing Rose and the four children to fend for themselves. This new circumstance contributed, in a roundabout way, to Newt’s arrival in Kansas City, Missouri. Rose briefly took the children to Cincinnati – presumably she had family there – and, shortly thereafter, Newt accompanied her to Missouri to visit an aunt whose young son had recently died. As Allen later recalled:

“I went to live with my auntie, Ophelia Henderson, in Kansas City. She had a boy and he and I were the same age. And he passed. And when she lost him, then she took me.

I lived at 17th Street, about 17th and Woodland. Just across the street from where I lived was a ballpark by one of them playgrounds. I was out there all the time. That was Parade Park.”3

Such were the unusual circumstances by which Newt grew up in Kansas City while his siblings were raised by their mother, first in Austin and later in Cincinnati.4

Allen attended Bruce Elementary School and Lincoln High School and became close friends with Frank Duncan, a future Monarchs teammate and manager. According to Allen, another future Monarchs star, pitcher Rube Currie, was also part of their circle of friends who played sandlot ball together.5 As Allen and his friends advanced from sandlot to semipro ball, he started to chase after balls from the minor-league Kansas City Blues’ games, saying, “[I would] come back with the ball and sell it or keep it. That’s the way our ballteam [sic], which was a semipro team, always had balls to play with when we would go out to play.”6 Allen also started to work at the Monarchs’ ballpark at 20th Street and Prospect where, he said, “I pulled the canvas and filled the water jug for them, things like that.”7 Allen and Duncan played for the semipro Kansas City Tigers, but Newt spent a lot of time on the bench and soon joined the Paseo Rats as well as playing for Swift’s in a packinghouse league.8

Duncan began his professional career with the Chicago Giants in 1920 – the same year that Currie debuted with the Monarchs – and joined Kansas City early in the 1921 season, but Allen had to take a longer road to join his longtime friends on their hometown team. First, he ventured to Nebraska, where he honed his skills playing for the Omaha Federals in 1921. Monarchs co-owner J.L. Wilkinson had resurrected his barnstorming All-Nations team – so called because it was integrated and employed players of different races and ethnicities – and based it in Omaha. He soon took notice of Allen and gave him a tryout in 1922, after which he assigned Allen to the All-Nations team, placing him under the tutelage of the diverse squad’s manager, already-legendary pitcher John Donaldson.

Allen toiled for the All-Nations team, which also served as a farm club for the Monarchs, for most of the season before being called up to the Monarchs in October for a six-game “City Championship” series against the Double-A Kansas City Blues.9 The Monarchs won five of the six games against their White counterparts to claim the title as champions of Kansas City. Allen fared poorly at the plate, going 1-for-14 for an .071 batting average in five games, but he nonetheless had learned well in 1922 and was able to break spring training with the Monarchs the next season.

Perhaps the reason for Allen’s poor performance in the City Championship series was that he was distracted by his early-October marriage to 17-year-old Mary Edwards and the impending arrival of their first child, Newton Henry Allen Jr., who was born on November 27, 1922. Newt Jr. eventually graduated from Western Baptist Bible College, the same institution his father had attended for two years before pursuing his baseball career, and he founded Kansas City’s Mount Joy Missionary Baptist Church.10 Newt Sr. and Mary had a second son and a daughter, but their marriage did not endure. Allen recalled, “After my wife and I separated, [teammate Newt Joseph] and I lived together here in Kansas City for about five years. The two Newts.”11

The difficulty in Allen’s marriage was representative of the problems that have shaken many ballplayers’ marriages in all eras. According to one historian, “[M]arried players always spoke of the ‘understanding’ a man and his wife had to have.”12 Allen said, “It’s a hard life. There has to be an understanding between you and your wife – a good understanding.”13 Whether that understanding entailed the expectation of marital fidelity or the acceptance of infidelity may have varied from marriage to marriage. Allen was known to revel in his celebrity as a ballplayer and confessed, “The women, they were lovely everywhere we went. If they didn’t recognize me in my regular clothes, then I’d go up to them and tell them who I was. But sometimes they could be a worrisome deal.”14

One concern that Allen hoped would no longer be worrisome was his status with the Monarchs, a member team of the Rube Foster-founded Negro National League. He began the 1923 season at third base with Kansas City and batted .304 in 33 league games but was returned to the All-Nations team in June and spent the summer barnstorming throughout the Midwest again.15 The Monarchs finished with a 54-32 league record (61-37 overall) and wrested the NNL championship away from Foster’s Chicago American Giants, the team that had claimed the first three league pennants. Although Allen had not spent the entire season with Kansas City, he still had been a major contributor to the first of the 11 Monarchs championship squads on which he played.

Finally, in 1924, Allen took over at second base for Kansas City for the long term. He gained his older teammates’ acceptance through hard play and by taking their pranks in a good-natured way. Allen noted, “The players would ride you to see if you can take it,” and recalled that one time some of the Monarchs veterans “told the hotel where we ate not to give me no meat because I’d have fits. I ate breakfast without meat and lunch without meat. So I asked them what was going on and they told me the players told them if they gave me meat, I’d have fits.”16 His first full season with the Monarchs involved a learning curve on the baseball diamond as his batting average fell to .258 and he committed 33 errors in the field in 73 league games; his .918 fielding percentage was slightly below the league average of .925.

In time, Allen remedied all shortcomings. He was not a big man – standing 5-feet-9 and weighing 165 pounds – so he learned how to become an ideal number-two hitter in the Monarchs lineup. Later in life, when asked what he considered to be his outstanding achievement in baseball, Allen answered that he “learned how to play second base, bunt and hit behind the runner, and think while playing.”17 That Allen was a fast learner was evidenced by the improvements in his performance at the plate and in the field as the Monarchs faced the Hilldale Club in the first Negro League World Series that October.

That first World Series provided as much excitement as any fan could desire. The Monarchs prevailed 5-4-1 over Hilldale. The tie occurred in Game Three, which had to be called due to darkness with the scored knotted, 6-6, after 13 innings. Allen improved his batting average to .282 with 11 hits (seven doubles) and 8 runs scored and his fielding percentage rose to .968. However, one of the two errors he committed proved costly.

In Game Four, which was played on October 6 at Maryland Baseball Park in Baltimore, the teams were tied, 3-3, when Hilldale loaded the bases in the bottom of the ninth. Hilldale catcher Louis Santop hit “a routine grounder to Newt Allen at second and Allen [threw] wildly to catcher Duncan, allowing Judy Johnson to score the ugly, but winning run.”18 Hilldale’s winning pitcher was Allen’s childhood friend Rube Currie, and the Philadelphia-area club took a 2-to-1 Series lead.

Allen was able to redeem himself in Game 10, which took place on October 20 at Schorling Park in Chicago. Hilldale’s Script Lee and Jose “The Black Diamond” Mendez, the Monarchs’ Cuban hurler, engaged in an epic pitchers’ duel that remained scoreless until the bottom of the eighth inning. In that fateful frame, the Monarchs offense exploded for five runs. Allen drove in the second and third runs with a single to right field and put the exclamation point on Kansas City’s rally by scoring the fifth and final run on Dink Mothell’s double. Mendez finished the shutout, and the Monarchs were the champions of Black baseball.

On the heels of Kansas City’s championship, Allen and Monarchs teammate Wilbur “Bullet” Rogan traveled to Cuba to play for the Almendares Alacranes (Scorpions) during the 1924-25 Winter League season. Almendares fielded four future Hall of Famers in Rogan, Raleigh “Biz” Mackey, John Henry “Pop” Lloyd, and Oscar Charleston and was the dominant squad on the island. In fact, “Almendares reclaimed the title by such ample margin that the league, as was customary in those days, stopped the activities to prevent financial harm to the different clubs.”19 Allen contributed a .313 batting average in 48 at-bats while splitting the third-base duties with Cuban Jose Gutierrez.20 With the regular season cut short, it was decided that a special eight-game series would be held between “All Cubans” and “All Yankees” teams. The All Yankees, composed exclusively of Negro League players, finished with a 5-2-1 record in the series, and Allen went 8-for-30 for a .267 average while playing third base in all eight games.21 He returned to Cuba only once, in 1938-39, and split the season between Almendares and Habana. He hit .269 combined between the two squads but fell short of a championship as the Santa Clara team won the title that season.22

In April 1925 the Chicago Defender noted that the Monarchs would field an all-veteran starting lineup to begin the season.23 Kansas City’s talent and experience led them to the NNL’s first-half title, but the St. Louis Stars captured the second-half flag, and it took a hard-fought seven-game series for the Monarchs to retain the NNL championship. Allen once again handled the second-base chores, batted .289 in 80 regular-season games, and raised his level of play and batting average to .370 in the NNL championship series against the Stars. The Monarchs’ reward was a rematch against Hilldale in the 1925 World Series. Between their exhausting series against St. Louis and an injury to pitching ace Bullet Rogan, who “was hurt in a freak accident at home and spent the entire series on the bench,” the Monarchs were no competition for Hilldale this second time around.24 Hilldale’s pitchers quieted Kansas City’s bats and captured the championship in six games. The Monarchs likely wished that Rube Currie had still been on their side, as their former righty, who had gone 1-1 with a 0.55 ERA in the 1924 World Series, posted two victories in the rematch. Currie threw a 12-inning complete-game victory in Game One and hurled another complete game in Hilldale’s 2-1 triumph in Game Five. Meanwhile, Allen slumped to .259 and only one Monarchs hitter – Dobie Moore – managed to bat over .300 for the Series.

Rogan recovered in time to play in the California Winter League’s 1925-26 season and Allen accompanied him west. The two played for the Philadelphia Royal Giants in what was at that time the only integrated professional baseball league in the United States. Allen scuffled to a .254 batting average in 29 games, but Rogan posted a 14-2 record to help the Royal Giants run away with the league title. Allen returned to California for the next five Winter League seasons, playing for the Philadelphia Royal Giants in 1926-27, 1929-30, and 1930-31 and for the Cleveland Giants in 1927-28 and 1928-29. During his six winters in the Golden State, Allen compiled a career .324 batting average, and his teams captured the league title every year except in 1927-28.

Allen’s career settled into a winning pattern in both California winters and Kansas City summers. However, as successful as the Monarchs were, they were unable to return to the World Series in 1926, losing a nine-game playoff series to the archrival Chicago American Giants. There had long been bad blood between the Monarchs and the Giants, and it brought out one of Allen’s less desirable traits: his temper. Chicago’s Dave Malarcher had once spiked Allen as he slid into second, opening a gash that required 18 stitches. Allen held a long grudge, recollecting, “It took me three years to repay him, but they say vengeance is sweet. One day we were leading by two runs, he was on first, and I took the throw at second for a double play. Well, instead of throwing to first, I threw straight at Malarcher charging into second. I hit him right in the forehead. … Hurt him pretty bad. He was out of the ball game for three days.”25

Malarcher was one of many players with whom Allen had run-ins during his long career in the rough-and-tumble Negro Leagues. In looking back, Allen admitted:

“A lot of times I had a nasty feeling within myself, not against a ballplayer. I was pretty bad playing ball, yes, I was pretty bad – run over a man, throw at him. I did a lot of wrong things. But I got results out of it, because they were leery of what I was going to do, and I’d get by with it. …

We used every trick in the book to win a ball game. All kinds of good tricks and nasty ones. In fact, there were more nasty ones than there were good. Caused many a ballplayer to get hurt.”26

Although Allen put fear into some opponents via the use of his “tricks,” he also gained the respect of his peers as one of the best second sackers to play the game. Pitcher Chet Brewer, who joined the Monarchs in 1925 and was a longtime teammate, raved, “Newt was a real slick second baseman, he could catch the ball and throw it without looking. Newt used to catch the ball, throw it up under his left arm; it was just a strike to first base. He was something! Got that ball out of his glove quicker than anybody you ever saw.”27 Buck O’Neil, who came to Kansas City in 1938 and who had an eye for talent as good as (or better than) Wilkinson’s observed, “When I got there, Newt was in his mid-thirties, but even after sixteen years he was an excellent second baseman, and he had six more good years left in him. He could make all the plays around the bag, and I’ve never seen a second baseman with as good an arm.”28 Even White baseball took notice, as New York Giants manager John McGraw asserted, “Allen is one of the finest infielders, white or colored, in organized baseball.”29

While their second baseman made a name for himself, the Monarchs franchise was about to embark on a new phase of its existence. Allen batted .332 for the 1929 squad as Kansas City won its final NNL championship by virtue of capturing the league title in both halves of the season, finishing with a 63-17 record in league play (66-17 overall). The Great Depression was taking its toll on NNL teams, and the league folded after the 1931 season. Wilkinson had seen the handwriting on the wall and withdrew the Monarchs from the league after the 1930 season, turning the franchise into a barnstorming team. Wilkinson figured that he could turn a profit via his innovative portable lighting system that had introduced night baseball to America in 1930. Thus, the Monarchs became an independent barnstorming team from 1931 to 1936. Although Allen spent the entirety of his career with the Monarchs, circumstances now forced him to seek employment with other teams for brief periods of time. Prior to the Monarchs beginning their barnstorming season, he played for the St. Louis Stars in 1931 and the Homestead Grays in 1932.

Additionally, while Allen had already been to Cuba, he soon got to see other parts of the world as well. On December 12, 1931, the Chicago Defender reported, “The Kansas City Monarchs left Tuesday morning for Mexico City to play a series of games. This trip is being made under the supervision of the Mexican government. The club will travel in a special Pullman and will be quartered in one of the best hotels in the southern republic.”30 The Mexico City Aztecas provided the primary opponent over the course of the 30-day tour, and newspaper accounts showed the Monarchs to have a 19-2 record.31

Two years later, during the winter of 1933-34, Allen and five Monarchs teammates – including his winter traveling companion Bullet Rogan – were members of a 12-player all-star team that toured China, Japan, and the Philippines. The three-month exhibition tour was organized by Lonnie Goodwin, the manager of the California Winter League’s Philadelphia Royal Giants, and the all-stars competed against Army teams and clubs from sugar plantations.32 On the return trip, the team played additional games in Hawaii. According to Allen:

“A man named Yamashiro, a superintendent down at Dole Pineapple Company, offered Rogan and me a salary and the only thing we’d have to do was check crates of pineapples and play ball two days a week, Saturdays and Sundays. At the end of the ball season, the team split all the money. The factory just furnished us the suits and the name. But we decided to come on back home and play.”33

Having returned stateside, Allen and Rogan, as members of the Monarchs, integrated the prestigious Denver Post Tournament in 1934 as they vied for the $5,000 purse that was to be awarded to the winners. The House of David team responded to the powerful Monarchs entry by hiring Satchel Paige (who later became more closely associated with the Monarchs than any other team he had played for) and catcher Cy Perkins of the Pittsburgh Crawfords as mercenaries to play for their otherwise all-White squad. Paige outdueled Chet Brewer, 2-1, in a semifinal game. The Monarchs made it to the championship game but again succumbed to the House of David, 2-0, as Brewer lost another duel, this time against Spike Hunter. Allen ended up being the tournament’s leading basestealer, but that was of no consolation to him or the rest of the Monarchs.

The Monarchs, along with Paige and Perkins, as the first Black players to participate in the tournament, had to deal with a great deal of discrimination in the press. The Post ran numerous insulting articles; in one item, “[a]cting as if Paige’s nickname of ‘Satchel’ wasn’t good enough, the newspaper invented a new one – ‘The Chocolate Whizbang.’”34 Like most Black players, the members of the Monarchs had long ago become inured to the prejudice they encountered in the age of Jim Crow, but sometimes they could be pushed over the limit. Allen recalled one incident when, after a Michigan restaurant owner told them they could not eat inside his establishment, “We just all walked out – we left them with fifty some hamburgers on the grill. It was one of those times when you even the score.”35

Although some White players also lacked racial tolerance, it was much rarer for the Monarchs to experience discrimination from the White players on local teams or major-league all-star teams that they played against. Allen explained, “Ball players – white and black – have a lot of respect for each other. They know they can play ball, and they know they’re going to play with them or against them. You hear a lot of harsh words from the grandstand, but very seldom find prejudiced ball players.”36

The Monarchs were also the only Negro League team under White ownership, and Wilkinson and his players gave mutual respect. Wilkinson was so proud of his players’ success in exhibition games against major-league teams that he once boasted “his team could compete with the New York Giants or Yankees, the two teams in the 1937 white major leagues’ World Series.”37 However, pride in their abilities alone would have meant little to the Monarchs players. They respected Wilkinson because of the way he treated them. Allen stated, “He was a considerate man; he understood; he knew people. Your face could be as black as tar; he treated everyone alike. He traveled right along with us.”38

In 1937 Wilkinson decided that the Monarchs would rejoin a league. The franchise became one of the charter members of the Negro American League rather than enlisting with the second iteration of the Negro National League that had been established in 1933. The Monarchs dominated their new competitors, claiming the NAL championship in five of the league’s first six seasons. They defeated two former NNL rivals now in the NAL, the Chicago American Giants and St. Louis Stars, in 1937 and 1939 respectively to win the pennant in those two seasons. From 1940 to 1942, Kansas City was declared the NAL champion by virtue of finishing with the league’s best record. Even when the title eluded the Monarchs in 1938, the team still owned the NAL’s best overall record; however, it failed to win either the first- or second-half league title.39

Allen batted .314 in 51 league games and continued to man second base for Kansas City as the franchise embarked upon its first NAL title run in 1937. However, over the next three seasons his batting acumen and defensive range began an inevitable decline. In 1941 the now 40-year-old Allen was moved to third base; he also took the managerial reins and guided the Monarchs to a 25-11 league record (34-13 overall) in his lone season as the team’s skipper. Despite the falloff in Allen’s overall play, he was a well-established, popular star and was elected to play in four East-West All-Star Games (1936-38, 1941).40 The fact that Allen went 0-for-15 with the bat in the four all-star contests, however, was one indicator that his best playing days were behind him.

Nevertheless, in 1942 Allen managed one last hurrah as he manned third base in 24 of the Monarchs’ 39 league games and batted .304. Kansas City won the NAL with a 27-12 record in league play (35-17) overall and earned the right to face the NNL’s Homestead Grays in the first World Series between the two rival leagues. Thus, almost two full decades after participating in the first-ever Negro League World Series, Allen now took part in another landmark event. The Grays ruled the NNL in the same manner as the Monarchs reigned over the NAL, so it was expected that this Series might be every bit as dramatic as its predecessor had been in 1924. The Monarchs had other ideas, however, and swept the Grays in four games. As a 23-year-old youngster, Allen had batted .282 against Hilldale in 1924. Now, at the venerable age of 41, he played in three of the four games and hit .286 against Homestead as he won the final championship of his long career.

After two subpar seasons, in which he batted .239 and .236, Allen voluntarily retired after the 1944 season. However, in March 1945 he was around in spring training to evaluate a new player for Wilkinson, a former college athlete fresh out of the Army by the name of Jackie Robinson. Allen’s assessment was, “He’s a very smart ball player, but he can’t play shortstop – he can’t throw from the hole. Try him at second base.”41 Although Allen identified the position with which Robinson would become most associated after breaking the White major leagues’ color barrier with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, Robinson won the Monarchs’ shortstop job by default in 1945 when starter Jesse Williams suffered an arm injury. Later in life, Allen continued to extol Robinson’s baseball acumen, saying, “Jackie was smart, he was an awful smart ballplayer. He didn’t have the ability at first, but he had the brains. … Jackie had one-third ability and two-thirds brains, and that made him a great ballplayer.”42

Allen had been a great ballplayer for a long time as well, and as is often the case with such individuals, he could not resist one final attempt at playing the game he loved. In April 1947 the Chicago Defender listed Allen on the roster of the NAL’s Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns, who now had future Hall of Fame shortstop Willie Wells Sr. as manager.43 Allen and Wells had formed the keystone combo for the St. Louis Stars in the first half of the 1931 season, prior to Allen’s rejoining the Monarchs for their barnstorming schedule. In his limited playing time with the Clowns, Allen turned back the clock at the plate, batting .314 in 13 league games, before hanging up his spikes for good. Wells did not have the same success as manager that he had enjoyed as a player and was replaced by Jesse “Hoss” Walker after the Clowns started the season 14-29. The Clowns finished fifth in the NAL with a 31-52-1 record, while Allen’s hometown franchise, the Monarchs, finished second at 52-32.

Once Allen’s baseball career was at an end, he settled in Kansas City, where he became involved in Democratic Party politics and worked as a foreman in the county courthouse. In the mid-1960s, Allen enjoyed attending yearly player reunions that were usually held in nearby Kansas City, Kansas. In 1971 he stated, “[T]he last five years we’ve had a reunion every year, all the ballplayers, white and colored [from the area’s former semipro and professional teams].”44 He also kidded, “You talk about hearing some baseball – everybody’s talking, and among the habitual drinkers, that’s when the truth comes out and there are some tall tales told. One guy says that’s the only time he ever hits .300, when he remembers the old days at those parties.”45

Eventually, Allen moved back to Cincinnati to be closer to family members who lived in the area. By the time the Kansas City Star interviewed him for a profile article in 1985, he was already residing in an assisted-care facility. In January 1986 Allen’s eldest son, Newt Jr., died. The Rev. Allen’s obituary listed as survivors his wife, Bertha; his father, Mr. Newton H. Allen Sr., of Cincinnati; as well as his mother, Mrs. Mary E. Allen, and a sister, Mrs. Myrtle Vanoy, both of Kansas City.46 No mention was made of Allen’s other son, who had made a career out of the Army and may also have preceded his father in death.47

Newt Allen Sr. died of a heart attack on June 9, 1988, at Cincinnati’s Golden Age Nursing Home. No obituaries were published in Cincinnati or Kansas City newspapers; only the Kansas City Times ran a short blurb about Allen’s death. In the Times’s brief write-up, Buck O’Neil was quoted as saying, “He was one of the best I’ve ever seen. I’d compare him with [longtime Kansas City Royal] Frank White, except Newt’s arm might have been a little stronger. He had soft hands and great range. The three best players I saw at the position were Newt, Frank and Bill Mazeroski.”48

Considering such accolades, it is even more distressing that Allen lies buried in an unmarked grave in Cincinnati’s Union Baptist Cemetery, a historical Black graveyard. In 2020 Negro League researcher/author Paul Debono and Cincinnati-area historian Chris Hanlin were able to identify Allen’s final resting place among other members of his family. Efforts began to enlist the aid of the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project and other entities to place a headstone at the site to commemorate the life of Newt Allen, one of the stars of the old Negro Leagues.

Sources

Ancestry.com was consulted for public records including census information; birth, marriage, and death records; military draft registration cards; and ships’ passenger logs.

California Winter League statistics and records were taken from: McNeil, William F., The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002).

Negro League player statistics and manager/team records were taken from Seamheads.com, unless otherwise indicated.

Sanford, Jay. The Denver Post Tournament (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2003).

Notes

1 “Teammates’ Tests Put Allen on Way to Long Career,” Kansas City Star, July 23, 1985.

2 This number includes first-half and second-half league titles, composite-standing league titles, and World Series championships. It is not to be understood as an assertion that the Monarchs won 11 World Series titles.

3 “Teammates’ Tests Put Allen on Way to Long Career.” Although Allen was raised in Kansas City from about the age of 9 years, the identity of his aunt is a mystery. Allen gave her name as Ophelia Henderson in the 1985 interview with the Star, but the only person by that name that this author could identify was younger than Allen; therefore, this Ophelia Henderson could not have been the woman who raised him. Allen may have mixed up names, especially as this interview was given late in his life. It also would not have been the first time he had told part of his life story inaccurately: In a 1971 interview with historian John Holway, Allen claimed to have been born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1902 (see John Holway, Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues, Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 91). Regarding Parade Park, it may be of interest to note that it is now the home of the Kansas City MLB Urban Youth Academy (see https://kcparks.org/places/the-parade-park/).

4 The 1920 US census shows that Rose Allen was still living in Austin; however, by the time of the 1930 census she had moved her family to Cincinnati permanently. Although Newton H. Allen had died in 1910, four children – two daughters and two sons – were added to the immediate family after his death; as there is no evidence that Rose ever remarried and all four had the surname Allen, it is possible that she adopted the children, perhaps from one or more relatives (as she had allowed her own son, Newt, to be taken in by a relative). Rose Allen died in Cincinnati in 1957 at the age of 81 or 82. (She was born in 1875, but her exact date of birth is unknown.)

5 Holway, 91. Rube Currie’s last name was also spelled “Curry” at times; see http://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=curry01reu.

6 “Teammates’ Tests Put Allen on Way to Long Career.”

7 “Teammates’ Tests Put Allen on Way to Long Career.”

8 Phil S. Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2010), 75.

9 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Munoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Newton ‘Newt’ Allen,” http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Newton-Newt-Allen.pdf, accessed December 29, 2020.

10 “The Rev. Newton H. Allen Jr.” (obituary), Kansas City Times, January 8, 1986, 39.

11 Holway, 93. Although Newt and Mary separated, this author uncovered no divorce records; thus, the couple may have remained married even though they ceased to live together.

12 Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Black Baseball (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1985), 43.

13 Bruce, 43.

14 Dixon, 76.

15 Revel and Munoz, 3.

16 “Teammates’ Tests Put Allen on Way to Long Career.”

17 “Newt Allen Questionnaire for Normal ‘Tweed’ Webb’s Record Book.” Thanks go out to SABR Negro League Research Committee Chair Larry Lester for providing a copy of Allen’s questionnaire.

18 Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006), 134.

19 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), 157.

20 Figueredo, 159.

21 Severo Nieto, Early U.S. Blackball Teams in Cuba: Box Scores, Rosters and Statistics from the Files of Cuba’s Foremost Baseball Researcher (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2008), 161.

22 Figueredo, 222.

23 “World Champion Monarchs Start Spring Training with All Veterans in the Lineup,” Chicago Defender, April 4, 1925: 10.

24 Kyle McNary, Black Baseball: A History of African Americans & the National Game (New York: PRC Publishing Ltd., 2003), 110.

25 Holway, 94.

26 Holway, 95.

27 Lester, 48.

28 Buck O’Neil with Steve Wulf and David Conrads, I Was Right on Time: My Journey from the Negro Leagues to the Majors (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 79-80.

29 Lester, 49.

30 “Monarchs to Play Series with Mexico,” Chicago Defender, December 12, 1931: 8.

31 Revel and Munoz, 10.

32 Bruce, 86-87.

33 Holway, 102.

34 Dixon, 144.

35 Bruce, 61.

36 Bruce, 80.

37 William A. Young, J.L. Wilkinson and the Kansas City Monarchs: Trailblazers in Black Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2016), 101.

38 Bruce, 19.

39 The Memphis Red Sox won the first-half championship, and the Atlanta Black Crackers clinched the second-half title in the 1938 NAL season.

40 The inaugural East-West game was played in 1933 while the Monarchs were an independent barnstorming team. Although Kansas City was still an independent team in 1936, the franchise’s players were eligible to be voted onto the West team for that season’s all-star game.

41 Bruce, 106.

42 Holway, 103.

43 “Red Sox to Play Three with Clowns” Chicago Defender, April 12, 1947: 23.

44 Holway, 104-5.

45 Holway, 105.

46 “The Rev. Newton H. Allen Jr.” (obituary).

47 Holway, 104. In this 1971 interview, Allen mentioned that his younger son was making a career out of the Army and was stationed in Europe at that time.

48 “Ex-Monarch Second Baseman Dies,” Kansas City Times, June 14, 1988: 30.

Full Name

Newton Henry Allen

Born

May 19, 1901 at Austin, TX (USA)

Died

June 9, 1988 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.