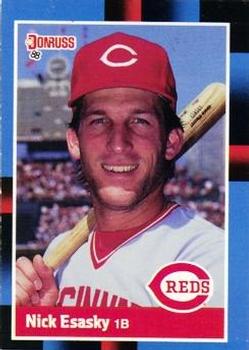

Nick Esasky

Three times, Nick Esasky hit 20 or more home runs in the major leagues – in 1985, 1987, and 1989. His peak season came at age 29 with the 1989 Boston Red Sox, when he played first base most of the season and hit 30 homers while driving in 107 runs, leading the ballclub in both categories. Not long after signing a lucrative free-agent contract with the Atlanta Braves, medical misfortune struck and derailed his playing career.

Three times, Nick Esasky hit 20 or more home runs in the major leagues – in 1985, 1987, and 1989. His peak season came at age 29 with the 1989 Boston Red Sox, when he played first base most of the season and hit 30 homers while driving in 107 runs, leading the ballclub in both categories. Not long after signing a lucrative free-agent contract with the Atlanta Braves, medical misfortune struck and derailed his playing career.

Esasky had been a first-round pick of the Cincinnati Reds in the June 1978 amateur draft, selected out of Miami Carol City Senior High School in Carol City, Florida.1 He was the 17th selection overall in that year’s draft.

Nicholas Andrew Esasky is right-handed and listed at 6-foot-3 and 185 pounds at the time of the draft. He was born in Hialeah, Florida on February 24, 1960. The family lived in Carol City, Florida at the time.2 Nick’s parents were Nicholas and Florian Esasky; Nick was the fourth of their six children, and the oldest boy. They came from Irwin, Pennsylvania, near Pittsburgh, and moved to Florida when Nick’s father Nicholas took a job as a mechanic for Eastern Airlines at the Miami airport.3 Nicholas worked other jobs, sometimes working second jobs to help support the family, but he worked for Eastern for 25 years. Florian Esasky was a stay-at-home mom with the six children to look after. The children were Cindy, Donna, Kathy, Nick, Sonya, and John.

In November 1979, Eastern Airlines accepted Nicholas Esasky’s request to be transferred to Atlanta, and the family found a home in Marietta. Nick had already completed his second season of pro ball. His entire family had always encouraged Nick’s ballplaying. “When my dad would take me out to practice – to hit – they would go out and shag balls for me. It was a family effort, and that carried through them watching me through high school, and into the minor leagues. When I got to the big leagues, they were a part of that as well.”4

He had played American Legion baseball. A shortstop in high school, in his senior year, Nick hit .392 with 10 homers and drove in 35 runs.5 He had been followed by the Major League Scouting Bureau and attracted considerable attention, being at times followed by as many as 17 scouts. He was recommended to Cincinnati by Philip Zelman, cross-checked by Gene Bennett, and signed by the Reds’ George Zuraw. Zelman was local and Zuraw an area scout, but Zuraw took the time and “really got to know the family quite well and made a connection with them. Being an honors graduate, I had full ride scholarship offers to the University of Miami, Auburn University, among many others. Through the relationship George had with my parents and the help from my high school coach Rob Hertler, we decided to sign with the Reds. They were all working hard behind the scenes and I was just out there having fun.”

Carol City High School also produced Randy Bush, who had been a couple of years ahead of Esasky but was drafted the following year out of Miami Dade College; and Danny Tartabull, who was drafted out of high school in 1980.

Bennett’s report to Zuraw emphasized Esasky’s defense, noting “rangy body, with good actions and agility. Has good accurate arm and hands are sure. Has good defensive instinct. Agility is good and is average ML runner.”6 Zuraw spoke to The Sporting News a few years later: “When I look at Esasky, I see the same power [Willie] Stargell showed. The kid has no idea how good he can be. He’s always been real serious. Now he’s learning to relax a little.” Comparing Esasky to Ray Knight, Zuraw said, “At the same age, Esasky has more than 10 times the ability Knight had. I’m talking a kid who could be a Mike Schmidt.”7

Graduating high school in June and drafted by the Reds, Esasky was placed in Rookie League ball with the Pioneer League’s Billings Mustangs. where he played well. In 64 games, he hit for a .305 batting average with four homers and 48 RBIs. He struck out about once a game but drew 43 walks and had a .421 on-base percentage.

Esasky spent 1979 in Single-A baseball with the Florida State League Tampa Tarpons. Throughout his minor-league years, he was consistently played at third base. He got into 124 games, batting .269 with 10 homers and 66 RBIs. In both of his first couple of years, he had what appears to be a rather high error rate – approaching 10% – but remained at third base.

Each year he advanced another level. In 1980, the year he turned 20, he was in his third season of pro ball and playing in Connecticut for the Double-A Eastern League’s Waterbury Reds. In 1981, he was at Triple A with the Indianapolis Indians in the American Association. His fielding percentage was .936 in 1980, but dipped to .896 with the Indians. He had begun to show more power with Waterbury, though, banging out 30 home runs with 79 RBIs, batting .271, in 135 games.8 He was named the league’s All-Star third baseman.9 His 30 homers were the most of anyone in the Reds system.10

After the 1980 season, Esasky was added to the Reds’ 40-man roster. Reds batting instructor Ted Kluszewski said, “You gotta like a kid with Esasky’s power. The kid has even bigger hands than Johnny Bench.”11

He spent two full seasons with Indianapolis, 1981 and 1982. His batting average was virtually identical (.265 and .264), and his RBI totals were identical – 62 runs batted in both years. But even though he played 16 fewer games in 1982, due to a few injuries, he hit 10 more homers – 17 in ’81 and 27 in ’82. Indianapolis won the American Association playoffs; Esasky helped with three home runs.

Esasky made the major leagues in June 1983. He had begun the season with Indianapolis once again, but after first baseman Dan Driessen went on the 15-day disabled list, Esasky was brought in to bolster the lineup. He already had 14 homers, and was batting .278, with 37 RBIs in 49 games, when promoted. He played his first game in the majors on June 19 against the Dodgers in Los Angeles. He batted sixth in manager Russ Nixon’s lineup. He grounded out to third base his first time up and struck out the second time. In his third at-bat, he hit a fly ball to center field. The entire Reds team managed only three hits that Sunday afternoon off Burt Hooton, who booked a complete game 5-1 win.

The next night the Reds were in San Francisco and Esasky got his first big-league hits – two of them. He singled his first time up, struck out, drew a walk, and then singled again in the top of the ninth. The Giants came from behind and tied it in the ninth, winning in the 10th.

His first run batted in came on June 21, another game in which every run counted. The Reds won the game, 6-5, in 16 innings. He had three hits in the game, with his single in the 14th giving Cincinnati a 5-4 lead, but the Giants came back to re-tie the game. With one out and right fielder Paul Householder on first, he singled again in the top of the 16th. Householder took second base, then scored on a single by second baseman Ron Oester. That run held.

His first home run was on July 1 in Atlanta, hit off future Hall of Famer Phil Niekro. It was an inside-the-park home run that hit off the top of the center-field fence,. The Braves ultimately won the game, 5-2. Two days later, still in Atlanta, his two-run homer off Craig McMurtry in the top of the sixth won the game, 2-1, for Cincinnati. On July 4, he drove in four on a sacrifice fly and a three-run homer off Donnie Moore, but the Braves won, 9-5. He hit four homers in a five-game stretch and got himself some headlines.12

Esasky stayed with the Reds the rest of the year.13 He suffered a slump in August but worked through it. In the end, he appeared in 85 games. Esasky contributed, batting .265 (the team average was .2539), driving in 46 runs in what was a bit more than half a season, and hitting 12 homers. Cincinnati finished in sixth (last) place in the National League West, 17 games behind the Dodgers. Esasky had more than held his own, however, and was back with the Reds for the next five seasons.

The Reds tried him out at first base in 25 games during 1984 and he split his time almost evenly between third base (62 games) and left field (54 games) in 1985, with some time at first base in 12 games. In 1986, he played 70 games at first base, starting 49 of them at the position. He played 42 in left field, and only one at third base. In 1987, he played 93 games at first base and again just one at third.

Esasky played in 100 or more games every one of his five full seasons with Cincinnati. After a fifth-place finish in 1984, Pete Rose took over as manager at the end of 1984. The Reds placed second in 1985 and remained a contender, finishing second, for four years running.

Esasky had a disappointing year in 1984. Vern Rapp was the manager, until the final month. Esasky hit .193 for the season, with occasional slumps but no dramatic ups and downs through the course of the season. From time to time, he was also plagued with back stiffness. It was not, of course, the kind of offensive production anyone hopes for, and well below any other year in his career. He had purchased a house in Kentucky, then realized he wasn’t being used as much earlier in the season, and that he might not remain with the Reds. His April 10 game against the Montreal Expos was the standout game of his season, with a sixth-inning grand slam off reliever Bob James and an RBI triple in the seventh, a game the Reds won, 8-6. But he was being used as a pinch-hitter, sometimes at first base, more often at third base, but there were 41 games in which he wasn’t used at all. “There wasn’t the consistency. If you had a slump, you couldn’t work through it.” It was a bit of an unsettled time – but the Braves had their eyes on Nick Esasky, even if his high number of strikeouts gave them some pause.14

In 1985, despite often platooning with Wayne Krenchicki, he was used more frequently and hit 21 homers (second on the team only to Dave Parker’s 34) and drove in 66 runs (second to Parker’s 125), batting .262 (with a .332 on-base percentage). He credited batting coach Billy DeMars with helping him turn things around.15 At the very end of July, Pete Rose switched Esasky from third base to left field. It wasn’t a move Esasky wanted; he had never played outfield, even in Little League. He asked about a trade if Rose intended to shift him to the outfield. Regardless, Rose wasn’t pleased that Esasky let the newspapers know. He grumbled, “I thought the name of the game was ‘team’.”16 Esasky did make the transition and worked left field for the last two months of 1985. Over the course of his career, Esasky played 98 games in the outfield and never once committed an error.

In 1986, Esasky struggled at the plate, batting .230 for the year. He hit 12 homers and drove in 41. It was very much an off-year. Appearing in about 2/3 of the games, he felt that – not being used as regularly as in the past – he was unable to develop a consistent routine. “I’d like a fair chance for one full season,” he said.17 Known as something of a streaky hitter, a couple of years later, he said this: “Who knows when I’ll be hot? If I’m not playing every day, I might be hot while I’m sitting in the dugout. All I’ve asked is to be put in there for one full season and let’s see what I can do.”18

A fractured right wrist during spring training 1987 resulted in his first game being on May 19. He missed the first 37 games of the season, getting a little rehab work in 13 games at Triple-A Nashville (batting .442 with five home runs). His second day back, on May 20, he hit a home run all the way out of Wrigley Field, over the left-field bleachers and over Waveland Avenue as well.19 Back in the majors, Esasky wound up playing in 100 games, 93 of them at first base. Despite missing as much time as he did, he hit 22 homers and drove in 59 runs, for a .272 batting average. There had been a couple of home-run clusters – on June 1, 2, and 3 he hit homers against the visiting Cardinals three games in a row, and starting on July 8, he homered in four consecutive games. The last of the four was a ninth-inning three-run homer that beat the Mets, 5-2.

His 1988 season saw him work in 122 games, with 15 homers but an uptick in RBIs to 62. His average dropped from .272 to .243, though his on-base percentage remained exactly the same at .327. He always hit better in Atlanta than most places (he commuted from his home in Marietta), but one stretch in July was particularly remarkable: on July 26, July 27, and July 28, he hit a game-winning home run each day.

The Boston Red Sox were after a left-handed reliever and acquired Rob Murphy from Cincinnati on December 13, 1988, with Nick Esasky as part of a package, for which the Reds dealt Todd Benzinger, Jeff Sellers, and a player to be named later (Luis Vasquez, in January). There was no love lost between Pete Rose and Esasky; both were glad to have seen the last of each other.20 Rose’s view was said to have been that Esasky’s “vast potential would always remain unlocked.”21 It was said that he may have mistaken Esasky’s quieter demeanor for a lack of competitive fire.22 One Boston writer thought it might be that Rose – a contact hitter – didn’t appreciate the tradeoff between the freer swinging Esasky, who struck out a lot but hit a fair number of home runs.23

Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy offered a profile of Esasky in a February Boston Globe article that summarized some of the reasons he perhaps hadn’t fit in as well in Cincinnati, for instance that he didn’t seem to show sufficient anger when he struck out. Rose was looking for someone showing more fire.24 Steve Buckley quotes Rob Murphy as saying Pete Rose was “Charlie Hustle,” but Nick Esasky was “Mr. Even-Keel.”25

Esasky did play first base for the Red Sox: 153 games at first base.

He impressed the fans at Fenway Park right away. In his first home game, he singled, doubled, and homered. The Red Sox had gone to the World Series in 1986 and made the postseason in 1988. Their 1989 season was a down year, but Esasky sparked a lot of attention: it was the best year of his career. By mid-September, local sportswriter Joe Giuliotti said that in acquiring him, the Red Sox had “pulled off one of the biggest heists in 50 years.”26 He was, however, on a one-year contract, a free agent after the season.

“This is the first time I’ve enjoyed playing ball in a long time,” Esasky said in August.27 Manager Joe Morgan was more than pleased. He used Esasky in 154 games, and Esasky being able to play nearly every game and all but one game at first base seemed to help.

Esasky’s 30 home runs led the team, 10 more than the 20 hit by Dwight Evans. His 108 RBIs also led the team: Evans had an even 100. Esasky hit a solid .277 and he had a .996 fielding percentage at first base. He was A.L. Player of the Month in August (sharing the honor with Toronto’s George Bell.) The Boston Baseball Writers voted him team MVP for 1989. The team finished third, six games behind the first-place Blue Jays.

Filing for free agency, many thought Esasky might end up with Atlanta, where he had always hit well, and which was near his home in Marietta. He was still just 29 years old. With three children in the family – Jennifer, Kimberly, and Nick Jr. – the opportunity to play half his games in the area where he and his wife made their home was a major factor in signing with the Braves in mid-November. The Braves’ offer was the biggest one, too: reportedly a three-year, $5.6 million contract.28

Esasky played in nine April games for the Braves. He had six hits, for a .171 batting average, but no extra-base hits and no runs batted in. He hurt his shoulder falling while fielding a grounder on April 21 and was charged with his fifth error in nine games, one in each of his last four games. After a number of tests to try to understand the dizziness and weakness from which he had suffered throughout much of the spring, his doctors determined that he had developed vertigo. A Boston Globe article offered details of his symptoms and the path he faced.29 His attempts to find an effective medication were not successful. He could still function on a daily basis, but not as a skilled athlete.

In June, after two months of tests, it was thought to have been caused by a virus of the inner ear.30 A month later, there remained uncertainty both as to accurate diagnosis and the cause. Was it Lyme disease? No one knew. He had at least 30 tests, by various physicians around the country, including a visit to the Mayo Clinic. More than six months into it, he said, “I always have some form of headache, unsteadiness…The one thing they have told me is that it is not life-threatening and that it will go away. But no one knows when.”31

As late as December, the prognosis remained uncertain, with some days better than others. The Braves felt they couldn’t wait, and so signed Sid Bream for 1991.32

After a lengthy rehabilitation program, Esasky demonstrated enough progress that he came to spring training and began to take batting practice in March 1991. He played in an exhibition game, but on the home front, he was hit with a demand for divorce. In mid-April, he said he wasn’t really making progress, and in May he had a setback – some fluid had seeped into his right retina, causing his vision to become blurred. In August, he was fitted for a custom mouthpiece to better align his jaw. He worked out with the Braves, but was nowhere near being able to play baseball. After the season, he was assigned to Greenville and removed from the 40-man roster. The chances another team might claim him in the Rule 5 draft were perhaps minimal, but he also had enough major-league service time that he could veto any claim he did not welcome.

He rejoined the Braves for spring training 1992 and expressed some hope of being able to come back mid-season. He played some rookie-level ball in West Palm Beach and, later, got into 30 games for the Triple-A Richmond (Virginia) Braves and put up some good stats at that level, batting .278 with five home runs.33 There was another hot stretch, when he hit three home runs over the course of five games, but it didn’t last.34

On July 17, the Braves released him, reportedly at his request.35

“After a little over two years of issues with the vertigo and me having to battle through that with all the tests and all the doctors and all the prodding and all the medication, it hadn’t helped me. I said I’m just going to try it without anything and see what I have. They didn’t feel that I was ready to come up. I realized, too…it’s not there. It was difficult to make that decision, but I couldn’t compete at that level. I was able to be released and I just walked away from the game. I didn’t go back to the stadium. I didn’t pick up my stuff from Atlanta. I just went home.

“It was a tough time for me all around. I was losing my career. I didn’t know about my health. For a couple of years – and even afterwards – they didn’t know what it was – why or what or how. I was potentially losing my family and my children. I was trying to reconcile with my wife who filed for divorce in’91, but it was not successful and the divorce was finalized in ’93.

“I remarried in ’94 and embarked on a very different journey. Life without baseball, having joint custody of my two children and coping with the effects of vertigo. That life was filled with a lot of good times but also included some heavy, dark, and negative times.

“Two decades of family court proceedings resulted in me making the most rational, intelligent, and right decision, which was to adopt my granddaughter; that was granted in 2012.

“My second marriage ended in 2019; on to my next journey.”

Compared to salaries 30 years later, what Esasky earned in baseball was relatively small, but it was large compared to most workers of the day and he was able to live off his savings, while investing from time to time in a number of projects, including some real estate investments. With the ups and downs of marketplaces over the years, there has been no steady return. Most of his investments did not pan out.

The vertigo still lingers, but he has learned to manage it. “What it’s caused me to do is be more cognizant of what’s going on around me. I have to concentrate more. There are times when I’m not real comfortable and have to stop. If there’s a lot of information coming in, loud noises, a lot of movement. If there’s a lot of commotion, it starts to wear on me.”

He has continued to work out and keep in good physical shape, both for his own sake and also to be able to continue raising his now 17-year-old granddaughter Skyla, and to spend time with son Nick and Nick’s wife Elise, their daughter Brinson, and another daughter on the way at the time of the interview.

Keeping his eyes and ears open, though, he discovered Corben Champoux, a young country music singer. With encouragement from his friend and mentor, Emmy Award winner Steph Carse, he formed Esasky Productions to promote her career. In late August 2021, her music video “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” video went to #1 on the Country Network in Nashville Week35 chart.

At the time of the 2021 interview, he had begun to give some hitting lessons. When in Windermere, Florida, before moving back to Marietta, he went to personal training school and then set up an LLC, Esasky Health and Fitness, but it has not developed into a formal program with a trainer and nutritionist. He had a new website in development: nickesasky.com.

His commitment to raising Skyla has required his company to remain on a back burner for now, but one can tell he has many ideas, in different areas, and hopes to be able to help encourage and support younger people in baseball with talent who are prepared to work at it the way he did.

Last revised: January 20, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Donna L. Halper and Bryan St. Amand and check for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, SABR.org, and the Nick Esasky player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Thanks to Rod Nelson for scouting information.

Notes

1 Carol City is a neighborhood in Miami Gardens, Florida.

2 Hialeah was the nearest hospital, and thus the city of his birth, but he was raised in Carol City and lived there through high school.

3 Nick was not Nick, Jr. For an appreciation of his father Nicholas Esasky, see: https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/atlanta/name/nicholas-esasky-obituary?pid=173057227

4 Telephone interview, Bill Nowlin with Nick Esasky, conducted on September 1, 2021, and September 10, 2021.)Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations attributed to Esasky come from these interviews.

5 Earl Lawson, “Reds See Gold in Esasky,” The Sporting News. February 14, 1981: 40.

6 Cincinnati Reds free agent prospect report, May 2, 1978.

7 Lawson, “Reds See Gold in Esasky.”

8 For a 1980 story on how Esasky was faring with Waterbury, see Don Harrison, “Waterbury Homer Record is Jeopardized by Esasky,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1980: 55. The record was 34.

9 “Pitching Ace Mark Davis Named Eastern’s MVP,” The Sporting News, September 20, 1980: 41.

10 Associated Press, “Ex-Waterbury Slugger High in Cincinnati’s Plans,” Hartford Courant, March 11,1981: D3.

11 Earl Lawson, “Hume’s Pay Gives Reds Early Chill,” The Sporting News, November 15, 1980: 52.

12 For instance, see “Esasky’s bat and glove spark Reds,” Atlanta Constitution, July 9, 1983: 4C.

13 A good summary of his first weeks in the big leagues may be found in Hal McCoy, “Skull ‘n’ Crossbones Readied for Esasky,” The Sporting News, July 18, 1983: 35, 36.

14 Gerry Fraley, “Smalley, Esasky top the list as Braves seek help at third,” Atlanta Constitution, June 6, 1984: 1D.

15 Dan Hafner, “Esasky Making Most of His Second Chance,” Los Angeles Times, April 18, 1985: F9.

16 Hal McCoy, “Deposed Reds Voice Gripes,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1985: 16.

17 “Reds,” The Sporting News, February 2, 1987: 41.

18 “Reds,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1988: 21

19 Hal McCoy, “Esasky Quieting Rumors,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1987: 16.

20 Rose griped that Esasky had been given the opportunity to become first baseman long-term but hadn’t taken advantage. Esasky said, “It’ll be glad to get out from under Pete Rose. I don’t know what it is or why it is, but Pete just doesn’t like me. I laugh when I hear people say what a great communicator Rose is. He isn’t. With him, you never know where you stand.” See “Reds,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1989: 53.

21 “Reds,” The Sporting News, April 1, 1989: 39.

22 Bill Zack. “Esasky Conquers Rose-Colored Past,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1990: 18.

23 Leigh Montville, “He will bring aura to Fenway,” Boston Globe, December 14, 1988: 57.

24 Dan Shaughnessy, “First impressions of Esasky,” Boston Globe, February 24, 1989: 58.

25 Steve Buckley, “New team, new look, new chance for Nick,” Hartford Courant, February 27, 1989: D5.

26 Joe Giuliotti, “Sox Hope That Esasky Isn’t One That Gets Away,” The Sporting News, September 18, 1989: 20.

27 Bob Ryan, “Esasky’s the good news of this season,” Boston Globe, August 13, 1989: 49. Ryan wrote that things had gotten so bad in Cincinnati that Esasky “would have welcomed a trade to the Los Angeles Clippers.”

28 Many of the considerations in signing with Atlanta are detailed in Paul Harber, “Esasky home as Brave,” Boston Globe, November 18, 1989: 33.

29 Nick Cafardo, “Their painful realizations,” Boston Globe, January 10, 1991: 77, 79. Cafardo’s article also discussed different problems plaguing teammate Tim Naehring.

30 “Esasky’s Dizziness Attributed to Virus,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1990: 15.

31 Associated Press, “Esasky day-to-day, seeking an answer,” September 29, 1990: F3B.

32 Claire Smith provided a detailed summary of Esasky’s situation. See “Fighting Back when Dream Becomes Nightmare,” New York Times, February 19, 1991: D13.

33 A summary of where he stood in the first part of July was presented by Mike Freeman, “Questions Never End for Esasky,” Washington Post, July 11, 1992: D1.

34 “Scouting,” Herald (Jasper, Indiana), June 10, 1992: 31.

35 “Esasky granted release,” Hartford Courant, July 18, 1992: B4F.

Full Name

Nicholas Andrew Esasky

Born

February 24, 1960 at Hialeah, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.