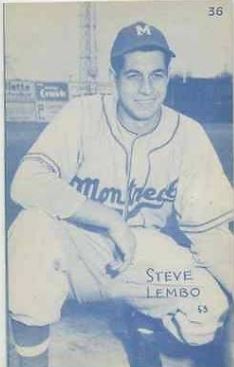

Steve Lembo

Catcher Steve Lembo was a lifelong New Yorker. He was born in Brooklyn, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and every one of his big-league appearances took place at Ebbets Field. In between those seven games, five in 1950 and two in 1952, he also played a small yet significant role at the Polo Grounds. On October 3, 1951, he was a bullpen catcher just before Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World.”

Catcher Steve Lembo was a lifelong New Yorker. He was born in Brooklyn, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and every one of his big-league appearances took place at Ebbets Field. In between those seven games, five in 1950 and two in 1952, he also played a small yet significant role at the Polo Grounds. On October 3, 1951, he was a bullpen catcher just before Bobby Thomson’s “Shot Heard ’Round the World.”

Lembo was stuck behind the great Roy Campanella, then in the prime of his Hall of Fame career, and backups Bruce Edwards and Rube Walker. He also faced intense competition in the minors. His time as a pro player, which began at age 17 in 1944, ended ahead of the 1953 season because of back problems. Nonetheless, he served the Dodgers organization for many years after that as an instructor and scout.

Stephen Neal Lembo was born on November 13, 1926. His father was Joseph Lembo, who worked in a ladies’ shoe factory. His mother, Lucia (née Lareno), stayed home with her three children. Steve’s younger brother Anthony played in the low minors for the Dodgers from 1956 through 1959. The boys had a sister named Anna.

The Lembos were of Italian origin. Joseph’s family came from the Naples area; his father was born in New York but lived in Italy for a couple of years as a boy before moving back. Lucia was born in Avellino, Italy (also near Naples). The family lived in Borough Park, a neighborhood in southwestern Brooklyn. Their home was a couple of miles away from the Parade Ground, the center of the borough’s thriving sandlot scene. Another mile or so farther north was Ebbets Field. While young Steve was growing up, he saw the Dodgers there as often as he could.1

Lembo took part in both baseball and basketball with the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO). He was a member of the entry sponsored by St. Catherine of Alexandria Parish.2 He also played in the Police Athletic League (PAL) for the 66th Precinct team.3 Both the parish and precinct served Borough Park.

In addition, Lembo and Tommy Brown both played for a team called the “Ty Cobbs” in Brooklyn’s Kiwanis League, whose director was Bill Dunn.4 Dunn later told the story of how Lembo rode up to him on a bicycle and convinced him that he could be manager of the Ty Cobbs. Lembo’s appetite for playing ball was so insatiable that after catching a morning game one day, he begged Dunn to be allowed to catch two more in the afternoon.5

Lembo attended New Utrecht High School, farther south in the Bensonhurst neighborhood.6 World War II was raging when he began his pro career. That spring, the Dodgers held workouts for select youngsters from the metropolitan area at their camp in Bear Mountain, New York. Nine of them went back to the city with pro offers. Of that group, the other one who made it to the majors was Tommy Brown — that August, in fact, at age 16.7

Lembo made such a favorable impression at Bear Mountain that he was first assigned to Newport News in the Piedmont League (Class B).8 He played just briefly there, however, and was sent to Zanesville in the Ohio State League (Class D). In 95 games, he hit no homers (power was not a big part of his skill set) but hit .314 and drove in 26 runs. Whereas he stood 6-feet-1 and weighed 185 pounds when fully grown, at that time he was still just 5-feet-11 and 160.9

Lembo then joined the Navy and was assigned to the aircraft carrier section.10 According to his family, he was not in combat. Basically, he played baseball while in the service. When he returned in the summer of 1946, he was assigned to Johnstown in the Middle Atlantic League (Class C). He got into 34 games and hit just .206. Still, he was promoted back to Newport News in 1947, and though his hitting remained mild (.228), he advanced again in 1948, to Pueblo in the Western League (Class A).

After hitting .286 in 94 games, Lembo jumped to Montreal in the Triple-A International League for 1949. There he posted a line of .291-2-21 in 90 games and was named to the IL’s all-star team.11 He also got into two games with Hollywood of the Pacific Coast League. The Dodgers added Lembo to their 40-man roster that October and let another catcher, Sam Calderone, go in the minor-league draft. Arch Murray of the New York Post likened the Dodgers system to a chain gang. Calderone rejoiced about his escape but was still sore about being passed over for Lembo and left “to die of old age or dry rot for all they cared.”12

Lembo had a powerful arm and was well regarded as a receiver. One who thought highly of him was pitcher Rex Barney, who’d had a disappointing year in 1949 and planned to go to spring training in Vero Beach a month early in 1950. He wanted Lembo to go with him as his practice catcher but wasn’t sure if his workmate could get away. At the time, both men had offseason jobs with a department store.13 That was Abraham & Straus, whose flagship store was in downtown Brooklyn. Lembo took this employment over an offer to play for Almendares in the Cuban winter league.14

The Dodgers had Lembo in spring training with them in 1950, as insurance in case Bruce Edwards, whose throwing was suspect, was still deemed to have a problem in that area.15 In fact, Brooklyn even considered making Lembo the number-two backstop if a good trade offer emerged for Edwards. However, the team couldn’t afford to deal Edwards because Lembo had to leave camp with a bad attack of flu.16 He started the season with Montreal, but the effects of his illness lingered well into June. The Dodgers even sent him to Pueblo in hopes that the Colorado air might help cure him.17 He injured his leg in his first game there; a few weeks later he was optioned to St. Paul in the American Association.18 He took part in just 21 games altogether, batting .226-0-7.

Lembo’s sons don’t remember that he ever talked about the competition he faced. Yet a look at the Royals and Saints in 1950 underscores the remark by his teammate in Montreal, Al Gionfriddo: “Baseball is a dog-eat-dog business.”19 Montreal’s primary catcher in 1950 was Toby Atwell, who (like Calderone) did not get his shot in the majors until he was out of the Dodgers organization. Backing up Atwell was Dick Teed, whose big-league career consisted of one pinch-hitting appearance for Brooklyn in July 1953. Over at St. Paul was veteran Ferrell Anderson, who’d played a lot for the Dodgers in 1946 but would not return to the majors until 1953, also with a different team.

Even so, Lembo made it up to Ebbets Field late in the 1950 season (rejoining his old Ty Cobbs teammate Tommy Brown). A foul tip dislocated Roy Campanella’s thumb on September 6, and Bruce Edwards (left foot) was also briefly unavailable. Thus, Lembo was summoned on September 15.20 He made his debut the following day against the St. Louis Cardinals, starting and handling Carl Erskine. Slow-footed Del Rice made one of his very rare steal attempts, but Lembo threw him out. With the bat, he went 0-for-2, grounding into a double play and flying out. With the game tied at 2-2 in the seventh, manager Burt Shotton lifted the rookie for pinch-hitter Eddie Miksis. St. Louis eventually won, 4-3.

Lembo also started the Dodgers’ next two games, against the Chicago Cubs. Brooklyn’s pitchers were Ralph Branca and Preacher Roe. Lembo got his first base hit in the majors against Bob Rush in the first of those games before Jackie Robinson came in to pinch-hit for him, again in the seventh. The following day, it was Gene Hermanski who batted for Lembo in the sixth.

Campanella returned to the starting lineup on September 19, even though his thumb (originally feared broken) was still swollen and had an angry red scar from six staples.21 Lembo played for the fourth straight day, replacing Campy in the eighth inning of a blowout 14-3 win for the Dodgers. Six days later, he got his last action of the season, entering in the ninth inning of a 4-3 loss to the archrival New York Giants. Altogether, he was 1-for-6.

Campanella played every inning in eight of Brooklyn’s remaining nine games. Even with doubleheaders on three straight days, the only respite he got was the nightcap of the first twin bill (which Edwards caught). Down the stretch, as Brooklyn tried to overtake the Whiz Kids from Philadelphia and win the NL pennant, Shotton used his bench very little. Yet Lembo still felt good about what he’d accomplished. “Working in those five games late in the season when Campy and Edwards were laid up gave me added confidence,” he said a few months later. “I’m confident I can do a capable job should the opportunity present itself.”22

That December, Lembo and Billy DeMars gave out the awards at the dinner celebrating the Ty Cobbs’ victory in the junior division of the Kiwanis League. The event was held at Andrew’s Restaurant in Borough Park. Co-owner Andrew Tedesco’s daughter Josephine later became Lembo’s wife.23

The field was still crowded in 1951, and Lembo stepped back down a level to Mobile in the Southern Association. He hit .260 with two homers in 115 games. Toby Atwell was still starting in Montreal; to back him up, career minor-leaguer Ken Staples was promoted. But when Staples broke a finger and then went into the Army, the Dodgers brought veteran George Pfister (a one-game major-leaguer in 1941) up from Class D (where he’d been a player-manager). Yet another catcher, Tim Thompson, was in St. Paul, with Teed in reserve. The big club also got a very capable new backup receiver that June, as Rube Walker arrived in an eight-player trade with the Cubs that also involved Edwards.

However, Lembo got the nod when Brooklyn needed catching depth amid more injury woes for Campanella. First Campy hurt his hip sliding on September 8, which prompted the Dodgers to call up Mickey Livingston.24 Then on September 17, he got beaned by Chicago’s Turk Lown. Since Mobile’s postseason had ended, Brooklyn manager Charlie Dressen wanted Lembo around, too; he arrived on the 19th.25

Lembo did not get into a game for Brooklyn in 1951, as Livingston made his last two appearances in the majors while Campanella recovered from his beaning. Though Campy returned to action in just five days, he pulled a hamstring in the 14-inning win over the Phillies that forced the playoff against the Giants. He could barely walk and needed a shot of anesthetic to take the field for the opener. He couldn’t play after that, so Rube Walker replaced him.26 Had anything happened to Walker, Livingston was apparently next in line.27

Meanwhile, Lembo served as bullpen catcher. His role in the third and deciding playoff game was uncovered in Joshua Prager’s book about the 1951 Giants, The Echoing Green. Prager, who interviewed Steve’s widow in 2002, said, “I recall the thrill of figuring out that it was Lembo in the bullpen catching Erskine. No one knew!”28

Erskine later clarified that he and Branca were each handled on an alternating basis by Lembo and coach Clyde Sukeforth, a catcher in his playing days.29 The pitchers were up in the eighth inning, even before starter Don Newcombe began to weaken in the ninth. The tying runs were in scoring position after Whitey Lockman’s double, and Dressen had to choose who would relieve Newcombe. In the pen, Erskine bounced a curve, and Sukeforth recommended Branca. Lembo also said that Branca had his stuff, as his sons recalled. Yet two pitches later, Bobby Thomson’s homer won the pennant for the Giants.

On October 20, 1951, Lembo married Josephine Tedesco, also known as “Jo” or “Josie.”30 (That same day, Branca married Ann Mulvey, the daughter of James and Dearie Mulvey, who were part-owners of the Dodgers.) She was a graduate of Notre Dame College, a small Catholic school for women on Staten Island, and a teacher at its affiliate for younger female students, Notre Dame Academy.31

Going into the 1952 season, Dressen said that the Dodgers would not carry a third catcher on the roster.32 George Pfister became the team’s bullpen coach, replacing the departed Sukeforth. When Roy Campanella chipped a metacarpal in July, Pfister might have been activated if necessary.33 Instead, Rube Walker played every inning of nine games in eight straight days.

Lembo remained at Class AA in 1952 but with Fort Worth in the Texas League. Splitting the catching duties with manager Bobby Bragan, he hit .221 in 81 games. Still, Brooklyn called him up in September. Yet again it was because Campanella was sidelined, this time with an infected left hand. However, Lembo took his time reporting, deciding to drive from Fort Worth to Brooklyn. By the time he joined the Dodgers in Boston on September 20 (oddly enough, he decided to fly the shorter distance), Campy was back in the lineup.34

Lembo made his last two big-league appearances that month. He was 1-for-5, getting his other big-league base hit off Curt Simmons of the Philadelphia Phillies. He got his only RBI in the majors on a groundout in his final at-bat.

After the season, New York sportswriter Jack Lang expressed a view that after Campanella and Walker, the Dodgers did not have a catcher ready for heavy duty. He described Lembo and Teed as fine receivers but questioned their hitting.35 Spring training 1953 found Lembo competing for a job with Brooklyn once again, but he was optioned to Montreal, and a recurring back ailment kept him out of action.36 In February 1954, aged 27, he decided to retire from baseball to concentrate on his job as a manager in the sports department of Abraham & Straus.37

Soon thereafter, the Brooklyn Eagle reported that Lembo was opening a series of baseball clinics for the CYO, in appreciation of the start he’d gotten as a boy. That winter he’d also conducted and supervised a well-received intramural basketball clinic for St. Catherine of Alexandria Parish. He was also a referee in CYO basketball.38

Lembo remained closely connected to the Dodgers organization. A July 1954 story showed him as a coach with the “Dodger Rookies,” a touring amateur team then co-managed by Art Dede.39 As several ads in The Sporting News noted, Lembo also served as an instructor at the Dodgertown Camp for Boys in Vero Beach. In addition, he was a productive scout. Two early finds out of Brooklyn were Bob Aspromonte and Tommy Davis, both co-signed with Al Campanis.40 Another, a few years later, was Al Ferrara.

While scouting, Lembo was a visible presence at the Parade Ground. Andy Mele, who was born in 1938, played there in the 1950s and ’60s. In his preface to A Brooklyn Dodgers Reader, Mele wrote, “I can still see Al Campanis and Steve Lembo behind first base, keeping alive the dreams of kids like myself.”41 Lembo was also mentioned in Mele’s book about Parade Ground ball, The Boys of Brooklyn.

Even after the Dodgers left for Los Angeles following the 1957 season, things were still happening at Ebbets Field, and Lembo was there. On August 22, 1959, a benefit game was held for the family of Charley Russo, a Dodgers scout who had died not long before. The Dodger Rookies faced the Brooklyn All-Stars, another squad of top high school and college youths playing in the local sandlot leagues. Lembo managed the All-Stars, and he had a future big-leaguer on his squad, pitcher Larry Yellen.42

Lembo continued to help out ballplayers with offseason jobs at Abraham & Straus. One was another Brooklyn native, Mike Fiore, who became a supervisor at the downtown Brooklyn store. As Fiore recalled, “Jake Wood worked there. Joe Pignatano worked there. [Joe] Pepitone. George Bamberger. [Lembo] said any players…if you’d go into any of the stores, or the main store, he’d give you a job for the winter. For a month, six weeks, or two hours. That’s what we did. The money was not what they’re making now.”43

Lembo’s scouting duties took him beyond New York City. For example, in June 1968 he was the featured speaker at a baseball dinner in Larchmont, Westchester County. He talked about what he and his colleagues sought most in young talent and explained the workings of the major-league draft, which was then in just its fourth year.44 Several days before, the Dodgers had drafted Bobby Valentine, a native of Stamford, Connecticut. Valentine was on their radar thanks to the team of Lembo and Rudy Rufer, the assistant manager of the Dodger Rookies in the Charley Russo benefit.45

On Long Island, Lembo and Rufer also helped find another big-leaguer: Kevin Pasley from Mineola in Nassau County. The Dodgers drafted the catcher in the 29th round in June 1971.

In the 1970s and ’80s, Brooklyn sandlot ball was still producing quality players, even if the fields were hardscrabble. One of the best players to come out of the scene then was John Franco, whom the Dodgers selected in the fifth round of the June 1981 draft on the recommendation of Lembo and his colleague Gil Bassetti.46

The New York press continued to mention Lembo here and there. One notable occasion came in April 1978, when the Marine Parkway Bridge (which connects Brooklyn to the Rockaway Peninsula in Queens) was renamed for his old teammate Gil Hodges. Daily News sportswriter Dick Young quoted Lembo: “Gil could never say no to a good cause. We were having this affair at A&S [Abraham & Straus] for the Greater New York Fund, and we needed somebody. I called up Gil. His father-in-law was sick, but he showed up at 8:30 in the morning. He never turned anybody down.” Also present at the dedication ceremony were Ralph Branca and Roy Campanella, “wheeled in, wearing his perpetual Roy Campanella smile.”47

Lembo was also a guest at parties celebrating the Dodgers’ glory years in Brooklyn. One came in May 1983, when the Brooklyn Union Gas Company and Abraham & Straus honored Lembo (who’d recently retired from A&S), Rex Barney, Al Gionfriddo, Joe Hatten, Gene Hermanski, Clem Labine, Cookie Lavagetto, Luis Olmo, and George Shuba. Barney recalled how he’d gotten his first offseason job at A&S thanks to Lembo.48

Another event, sponsored by the Downtown Athletic Club, came in October 1985 and celebrated the 30th anniversary of Brooklyn’s only World Series title. In addition to Lembo, Carl Erskine was on hand at Ponte’s Restaurant in Manhattan, as were Hermanski, Tommy Holmes, Joe Pignatano, and Jimmy Romano.49

With the Dodgers, Lembo reported to his old teammate Dick Teed, who was the team’s East Coast scouting supervisor from 1977 through 1992. Teed told author Lee Lowenfish (Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman) about how Lembo used to open up his summer home in the Hudson Valley after the end of each minor-league season. All the scouts and their wives and families enjoyed a convivial weekend celebration. On Saturday, the men talked baseball and played golf, and then Josephine Lembo served a spaghetti dinner. After that, she sent them off with Sunday spaghetti lunches.50

Bob Miske, a longtime scout for the Dodgers and later the New York Yankees, recalled those weekends very fondly as the high points of each year. He described Lembo, whom he knew for more than 30 years, as “one of the nicest people you could ever meet. A great scout but even better human being. Well loved.”51

Miske also remembered how he, Teed, Lembo and their wives went to Italy after the Dodgers won the 1988 World Series. Team owner Peter O’Malley treated the entire organization as a reward for the championship.52

Lembo remained a scout for the Dodgers until the end of his life. Baseball America’s 1989 directory showed him based in South Ozone Park, a neighborhood in Queens just north of JFK Airport. That made it easy for him to pick up visiting colleagues. The Dodger scouts covering the Northeast sometimes met before the season at the Lembo house, and they discussed their prospects and “follows,” as well as some of the players they missed. During these weekends, too, Josephine fed them well with her pasta meals.53

In the summer of 1989, thanks to Lembo and Gil Bassetti, Los Angeles made New Jersey’s Eric Young a 43rd-round draft pick. Young was Steve Lembo’s last notable find. He died on December 4, 1989 in Flushing, Queens. He had been suffering from diabetes, and then an infection in the hospital affected his heart. He and Josie had six children: Joseph, Judy, Lucia, Stephen Jr., Neil, and Andrea. Lembo was buried in St. Charles Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York, to the east in Suffolk County.

In recognition of this man’s support for amateur baseball, the New York Professional Baseball Hot Stove League presents the Steve Lembo Memorial Award.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Steve Lembo Jr. and Neil Lembo for their input (e-mail, June 20 and June 21, 2018), as well as Bob Miske (e-mail, June 21, 2018). Continued thanks to SABR members Andy Mele, Rod Nelson, Lee Lowenfish (Lee provided introductions to the Lembo family and Bob Miske), and Bill Nowlin.

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 “Watching Brooklyn Dodgers Gave Lembo Many Thrills,” Zanesville (Ohio) Signal, June 19, 1944, 7.

2 Jimmy Murphy, “To Run Clinic,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 25, 1954, 20.

3 “66th, 68th Pcts. To Honor P.A.L. Aces at Loew’s,” Brooklyn Eagle, November 11, 1952, 13.

4 “Obituary,” The Sporting News, October 10, 1951, 29. “Knife & Fork League,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1952, 22.

5 “Honor Ty Cobbs at Victory Fete,” Brooklyn Eagle, December 12, 1950, 18.

6 “Josephine Tedesco, Stephen Lembo to Wed,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 15, 1951, 18.

7 “Dodger Farms Sign Nine,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1944, 18.

8 “Kiwanis Group Aids Baseball,” New York Sun, March 28, 1944, 22.

9 “Watching Brooklyn Dodgers Gave Lembo Many Thrills.”

10 Joe Lee, “Five New Faces Sign Flock Pacts,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 31, 1951.

11 Cy Kritzer, “Buffalo Won Flag with One All-Star,” The Sporting News, September 14, 1949, 29.

12 Arch Murray, “Sam’s ‘Now a Name Instead of a Number,’” The Sporting News, March 15, 1950, 20.

13 Harold C. Burr, “Borneo Barney to Start Early in Effort to Tame Wild Tosses,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1949, 13.

14 Pedro Galiana, “Old Rivals Join Forces; [Dolf] Luque Will Aid [Mike] Gonzalez,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1949, 20.

15 Harold C. Burr, “Some New Talent with Dodgers — but Barney Has Old Problems,” The Sporting News, March 8, 1950, 10.

16 “Training camp briefs,” The Saratogian (Saratoga Springs, New York), March 31, 1950, 8. “International League,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1950, 32.

17 Ben Gould, “Down on the Farm,” Brooklyn Eagle, June 24, 1950, 6.

18 “Dodgers Option Lembo to St. Paul,” Albany Times Union, July 12, 1950, 14.

19 Richard Goldstein, “Al Gionfriddo, 81; Remembered for ’47 Catch.” New York Times, March 16, 2003.

20 “Dodgers Recall Catcher,” Buffalo Courier-Express, September 16, 1950, 18.

21 “Bums Flag Hopes Lifted as Doctors OK Campanella,” Altoona Tribune, September 8, 1950. “Camp to Catch,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 23, 1950, 10.

22 Lee, “Five New Faces Sign Flock Pacts.”

23 “Honor Ty Cobbs at Victory Fete.”

24 “Livingston Recalled as Sub for Campy,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 11, 1951.

25 Jack Lang, “Dressen Needs Catcher to Replace Campanella,” New York Star-Journal, September 18, 1951, 13. “Sad Birthday for Snider,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 20, 1951, 19. The Sporting News of September 26, 1951 shows that Mobile, with Lembo catching, played its final game on September 15.

26 Glenn Stout, The Dodgers, New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2004, 181-182.

27 John W. Fox, “Familiar TC Faces Seen at Ebbets Field,” Binghamton Press, October 2, 1951, 20.

28 Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green, New York: Pantheon Books, 2006: 206. E-mail from Joshua Prager to Rory Costello, May 23, 2018.

29 Carl Erskine, telephone interview with Andy Mele, March 2014.

30 “N.L. Notes,” The Sporting News, October 3, 1951, 15.

31 “Josephine Tedesco, Stephen Lembo to Wed.”

32 “Bunts and Boots,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1952, 25.

33 Roscoe McGowen, “X-Ray Shows Broken Digit; Campy’s Hand Put in Cast,” The Sporting News, July 30, 1952, 7.

34 “Dodgers Still Seek Catcher Lembo,” Schenectady Gazette, September 18, 1952. “National League,” The Sporting News, October 1, 1952, 30.

35 Jack Lang, “Bench and Baseline,” Nassau Review-Star, November 12, 1952, 25.

36 “International League,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1953, 28. Ben Gould, “Down on the Farm,” Brooklyn Eagle, July 9, 1953, 18.

37 “Lembo Retires for Store Job,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954, 24.

38 Murphy, “To Run Clinic.”

39 “8 Brooklynites Dodger Rookies,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1954, 40.

40 Jimmy Murphy, “Fleet-Footed Aspromonte Was Schooled by Pee Wee] Reese,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, February 24, 1959, B3. “Al Zucks Is Honored by Westchester Umps,” Yonkers Herald Statesman, June 12, 1968, 74.

41 Andrew Paul Mele, A Brooklyn Dodgers Reader, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005, xi. E-mail from Andy Mele to Rory Costello, May 25, 2018.

42 Murphy, “Duel of Strategy Between Scouts of L.A. Dodgers,” New York World-Telegram and Sun, August 22, 1959, B4.

43 Telephone interview, Mike Fiore with Bill Nowlin, June 5, 2018.

44 “Al Zucks Is Honored by Westchester Umps.”

45 John Altavilla, “Bobby Valentine No. 12 on State List of All-Time Athletes,” Hartford Courant, December 21, 1999. Tommy Lasorda, then managing in the minors for the Dodgers, also played a role while Valentine was visiting the University of Southern California. Ken Borsuk, “Bobby Valentine talks about the importance of luck,” Greenwich (Connecticut) Time, November 16, 2016.

46 Andrew Paul Mele, “The Elysian Fields of Brooklyn: The Parade Ground,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2012.

47 Dick Young, “Gil’s Fans; Gil’s Bridge,” New York Daily News, April 5, 1978.

48 George Vecsey, “Remembering the Dodgers,” New York Times, May 30, 1983.

49 Angela Canaday, “Angela,” Home Reporter and Sunset News (Brooklyn, New York), October 18, 1985, 29.

50 Lee Lowenfish, “Eyeball to Eyeball, Bellybutton to Bellybutton: Inside The Dodger Way of Scouting,” originally published in The National Pastime, Society for American Baseball Research, 2011. Bob Miske, e-mail to Rory Costello, June 21, 2018.

51 Miske e-mail.

52 Ibid.

53 Ibid.

Full Name

Stephen Neal Lembo

Born

November 13, 1926 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

Died

December 4, 1989 at Flushing, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.