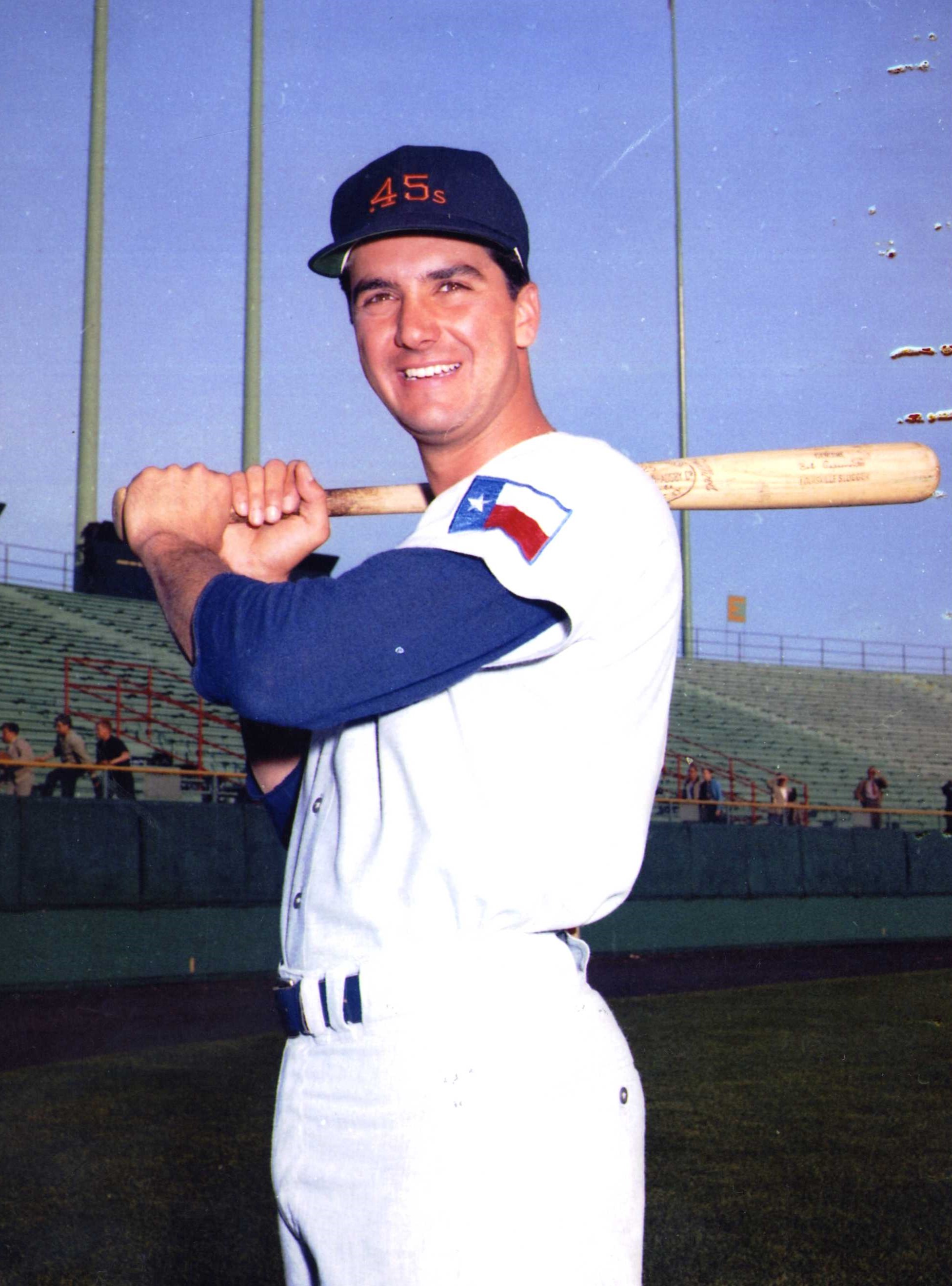

Bob Aspromonte

April 10, 1962, is an important date in the history of baseball in Houston, Texas. It marked the culmination of years of effort by George Kirksey, Craig Cullinan Jr., Roy Hofheinz, and R.E. “Bob” Smith to bring major-league baseball to Houston. The newly minted Houston Colt .45s played their first official National League game, defeating the Chicago Cubs 11-2.

April 10, 1962, is an important date in the history of baseball in Houston, Texas. It marked the culmination of years of effort by George Kirksey, Craig Cullinan Jr., Roy Hofheinz, and R.E. “Bob” Smith to bring major-league baseball to Houston. The newly minted Houston Colt .45s played their first official National League game, defeating the Chicago Cubs 11-2.

Nine professional baseball aspirants staked their claim to be consistent starters for the Colt .45s. Of these nine, only Al Spangler and Bob Aspromonte carried over to the 1963 Opening Day lineup card. And only Aspromonte carried over to the 1964 Opening Day lineup card. Aspromonte’s name appeared in every Opening Day starting lineup for Houston through 1968, the year he was traded to the Atlanta Braves. Aspromonte, fondly nicknamed “Aspro” in Houston, never started on Opening Day during his two seasons in Atlanta. After his trade to the New York Mets in 1971, Mets manager Gil Hodges penciled in Aspromonte as his Opening Day third baseman. Aspro batted .296 in eight Opening Day starts, going 8-for-27 with six runs and four RBIs.

Along with the distinction as the only original Colt .45 to appear in Houston’s first seven Opening Day lineups, Aspromonte achieved a number of franchise firsts. He was the first expansion-draft selection to take the field for the team. He was their first batter, hitting leadoff in the first inning on Opening Day. Aspromonte connected for the first hit, singling to left field on the first pitch from Cubs starter Don Cardwell. Moments later, Aspromonte scored the first run when Al Spangler tripled down the right-field line. He drew the first base on balls and subsequently scored the second run; while he was on base, Roman Mejias hit the first home run. Aspro stole the first base, taking second base in the eighth inning ahead of Mejias’ second home run of the day. He was the first player to reach base four times in a game, going 3-for-4 with a walk. On April 24, 1965, Aspromonte became the first Houston player to homer in the newly opened Astrodome against Vern Law as part of a 5-0 Astros victory over Pittsburgh.

Apart from these significant firsts, Bob Aspromonte also has two historic “lasts.” In addition to being the final original Colt .45 to start on Opening Day for Houston in 1968, he was the last active player in baseball (he retired in 1971) to wear the uniform of the Brooklyn Dodgers. He had one at-bat for Brooklyn in September of 1956 as an 18-year-old fresh out of Lafayette High School.

Robert Thomas Aspromonte was born on June 19, 1938, to Angelo and Laura Aspromonte. He was the youngest of their three sons, all of whom played professional baseball. The Aspromonte boys were raised in the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn, an area that was noted for its large constituency of Italian and Jewish residents. Aspromonte felt fortunate to be raised in a family and neighborhood where he was surrounded by athletic activities. Most of the Aspromonte household were fans of the Dodgers. Young Bob became the outlier when he developed a fondness for the New York Yankees, to the consternation of the rest of his clan.

As a child and teenager, Aspromonte participated in the Brooklyn Grasshopper, Little League, Kiwanis, Shore Parkway, and Coney Island baseball leagues, helping several of his teams to win titles. He was an all-star in the Coney Island and Kiwanis Leagues and won a Kiwanis Most Valuable Player Award. He captained his high-school baseball team during his senior year. In addition to baseball, Aspro played basketball at Lafayette. He came off the bench on his high-school varsity team, most of whose players were Jewish. Pertinent to that topic, Aspromonte noted that Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax was two years ahead of him at Lafayette, and won notoriety not in baseball but basketball. He said that Koufax, who pitched very little in high school, was the team’s first baseman.

Aspro’s brother Ken, older by seven years, played for six teams in a seven-year major-league career, followed by three seasons in Japan and another three managing the Cleveland Indians. Their father, Angelo, was a respected infielder in Brooklyn sandlot baseball in his youth. He augmented his youngest son’s interest in baseball by taking him to an Interstate League game in 1950. Bob was 12 at the time. Their main objective was to see a talented 19-year-old outfielder play for Trenton. The prospect would hit .353 in 306 at-bats. His name was Willie Mays, and the following year, he was called up to the New York Giants.1

Aspromonte’s fond memory of this experience with his father was complemented by the influence of his brother Charles. Eleven years his senior, Charles mentored Bob’s early development. After playing baseball in Bensonhurst, Charles played at New York University on his way to the Kingston Colonials and Sunbury A’s, Class-B affiliates in the Philadelphia Athletics farm system. Charles played with and tutored young Bob, even acting as his guide and agent to steer him professionally. Since Bob was only 17 when he tried out with the Dodgers, Charles had to act as his legal guardian through the signing process. This was not just because Angelo was busy supporting his family — he worked for 50 years as a brick mason — but because Charles, from his years in college and professional baseball, had acquired the know-how and confidence to guide his younger brother. As Aspro remembered, Angelo’s support for his sons’ athletic pursuits was a given: “I work. I want you guys to play baseball, because you have the talent.”2

After graduating from high school, Aspromonte was invited to try out with five different teams, including the St. Louis Cardinals and the Brooklyn Dodgers. As an early admirer of Marty Marion, Aspromonte was tempted to sign with the Cardinals. Ultimately, however, he was influenced to sign with the Dodgers due to their strong local connection. It helped that his friend Michael A. Napoli Jr. also played in the Brooklyn system. Brooklyn scouts Al Campanis and Steve Lembo recommended Aspromonte to general manager Buzzie Bavasi, who invited him to his office to discuss terms. Aspro’s first contract with the Dodgers was for $7,000 for two years.3 Here is how Campanis assessed Aspromonte in his scouting report:

“What first attracted my attention was his batting form. He does things naturally up there. He’s smart and always seems to know what he’s doing. He’s got an old head on a pair of young shoulders. And he not only can hit the long ball occasionally, but he seldom strikes out — usually gets a piece of the ball … that’s an important asset.”4

Initially, Aspromonte aspired to attend Long Island University to obtain a bachelor’s degree in physical education. However, the urge to turn professional led him to the Dodgers, who signed him on July 20, 1956.5 The Dodgers sent Aspromonte to Macon in the Class-A Sally League. After playing 13 games, he was recalled to Brooklyn in September. His big-league debut took place on September 19. As part of a 17-2 rout of the Cardinals, Walter Alston sent Aspro to pinch-hit for Sandy Amoros in the eighth inning. He laced a couple of line drives foul off pitcher Don Liddle before swinging for a third strike.

Although Aspromonte played only the one game for Brooklyn, he was invited to accompany the Dodgers on a goodwill trip to Japan after the World Series. Aspromonte spoke fondly of his memories of Japan.

Aspromonte was in awe of the famed Dodgers surrounding him. He remembered that Jackie Robinson was one of the first to take an interest in him. Robinson noticed that Aspromonte played infield with a large outfielder’s glove. With unmistakable reverence, Aspromonte recalled that Robinson gave him one of his own smaller gloves and invited Aspro to work out with him. Sandy Koufax had preceded Aspromonte to the Dodgers by one year, and the Dodgers put the two Lafayette alumni together as roommates that September.

Military service remained compulsory for young American males in 1957. However, it marked the first year of a new program that allowed recruits to join the Army for six months before participating in the Reserve for the next seven years. Walter O’Malley’s son Peter was one year older than Aspromonte. As Aspromonte remembered, he “really took care of me.”6 The elder O’Malley arranged for Peter and Aspro to enter the freshly launched Army Reserves program together.

Upon his discharge from the Army, Aspromonte was returned to Macon, where he hit .311 in 48 plate appearances. From there he was sent to Class-D Thomasville of the Georgia-Florida League. Aspro hit .263 in 228 plate appearances with a .344 on-base percentage, including five doubles, three triples, and his first professional home run. Impressively, he struck out only 14 times, demonstrating an early flair to make contact. In 1958, the Dodgers’ first year in Los Angeles, they assigned Aspromonte to Class-A Des Moines of the Western League. Playing alongside Ron Fairly, he hit .263 in 531 plate appearances with only 48 strikeouts.

In 1959 the Dodgers promoted Aspromonte to their Triple-A International League affiliate in Montreal, where he was reunited with former Brooklyn teammate Sandy Amoros. As the Royals’ starting shortstop, he hit .259 in 451 plate appearances. Also on that Montreal team was a 31-year-old pitcher named Tom Lasorda, who went 12-8 with a 3.83 ERA.

After batting .412 with the Dodgers in spring training, Aspromonte finally made the Dodgers’ Opening Day roster in 1960. With Maury Wills at shortstop, Jim Gilliam at second base, and Charlie Neal and Daryl Spencer as fellow utility players, Aspro’s playing time was limited to 21 games. Aspromonte demonstrated a flash of his potential at Los Angeles Coliseum on May 5. He went 4-for-5, including his first big-league home run. In the bottom of the 10th, Aspromonte hit a bases-loaded, two-out, two-strike single to drive home Wally Moon with the winning run.

Then Aspromonte went 5-for-37, prompting the Dodgers to option him to Triple-A St. Paul, where he could see more playing time. There he blossomed. He hit .329 with a .390 on-base percentage and 27 extra-base hits in 411 plate appearances, striking out only 38 times. After Aspromonte hit .330 in the Venezuelan Occidental League, missing the batting title on the season’s last day, the Dodgers kept him in Los Angeles for the entire 1961 season. Still, he took the field for only 15 games and only five as a starter. He was not getting the playing time he needed in order to develop.

Then the National League expanded to include new teams in New York and Houston. On October 10, Houston general manager Paul Richards won the coin flip to determine who would pick first in the expansion draft. Aspro was selected as the third overall pick.7 Though initially disappointed not to have been chosen by New York, as it would have brought him home, he soon warmed to the idea of playing in Houston.

In his first season in Houston as the Colt .45s’ third baseman, he played in 149 games in 1962, including 142 at third base. His slash line was .266/.332 with 18 doubles, 4 triples, and 11 homers. Although they trailed the pennant-winning San Francisco Giants by 36½ games, these numbers do not tell the whole story of “the little expansion team that could.”

The Giants’ record at Candlestick Park was 61-21, and the Colt .45s were the only team to win a season series there in 1962 with a record of 5-4. Only a pair of solo home runs by Willie Mays and Ed Bailey in the season finale gave the Giants a 2-1 victory and prevented the Los Angeles Dodgers from advancing straight to a World Series vs. the Yankees. Aspromonte went 2-for-4 in a losing effort for Dick Farrell. Despite a 64-96 eighth-place finish, Houston’s expansion team was in position to affect the outcome of the pennant race on the last day of the season.

While finishing 1963 with a record of, 66-96, the season proved to be more difficult for both the Colt .45s and Bob Aspromonte. He played in only 136 games, with a .214/.276 slash line. Star reliever Jim Umbricht was diagnosed with cancer and began treatments at Houston’s M.D. Anderson Hospital; he died on April 8, 1964.8 Despite these lows, the season had its highlights for Aspromonte. On May 12, the Colt .45s behind Don Nottebart trailed the Cubs 1-0 entering the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, 19-year-old rookie Rusty Staub tripled to drive home Johnny Temple and send the game into extra innings. Meanwhile, Umbricht, pitching while fighting cancer, preserved the tie with two scoreless innings. Then in the bottom of the 10th, Aspromonte hit a walk-off homer off Bob Buhl.

Also in 1963, an unusual and extraordinary human-interest story involving Aspromonte and a 9-year-old boy named Billy Bradley reached its zenith. The story actually began on April 30, 1962. While drinking water at a fountain in El Dorado, Arkansas, Billy was struck by lightning. Although he survived, the bolt robbed him of his vision. Billy’s family took him to Houston for ophthalmology treatments with Dr. Louis Girard. While undergoing a series of surgeries to restore his eyesight, Billy listened to the Colt .45s on the radio. He soon adopted Bob Aspromonte as his favorite player.

Eventually the Colt .45s were notified of Billy’s request for Aspromonte to visit him at Houston’s Methodist Hospital. Accompanied by teammate Joe Amalfitano, Aspro visited Billy on May 7, 1962, bringing a glove, a ball, a transistor radio, and Colt .45s pajamas as gifts. Before the players left, Billy asked Aspromonte to hit a home run that night against the Dodgers. Aspro countered that while he was not a home-run hitter, he would try to honor the boy’s request.9

Houston built a 5-0 lead by the second inning, only to trail the Dodgers 6-5 in the seventh. With two runners on base in the bottom half of the inning, Aspromonte came to bat. He was 2-for-3 to that point with two singles. On a 3-and-1 pitch from lefty Pete Richert, Aspromonte lined a three-run homer to provide the margin of victory in Houston’s 9-6 win. At the same time, he consummated the improbable scenario of delivering on an offer to hit a home run for a child.

The Bradley family returned to Houston in 1963 for additional eye treatments. Aspromonte took them to lunch on June 11, and again Billy asked Aspromonte to hit a home run for him. Battling chronic back pain, Aspromonte was struggling through perhaps his worst season in uniform. Although batting a feeble .198, he nevertheless told Billy that he would try to deliver another home run for him against the Cubs.10

The Cubs and the Colt .45s went into extra innings deadlocked at 2-2. Pitcher Hal Woodeshick led off the 10th inning with a single against Lindy McDaniel and was lifted for pinch-runner Bob Lillis. Ernie Fazio bunted and a throwing error by Ernie Banks advanced the runners to scoring position. Brock Davis was walked to load the bases for the struggling Aspromonte. One-for-four on the night with a single, Aspro faced his final chance to deliver on Billy’s request. Accordingly, he hit a 2-and-2 pitch on the screws, delivering a walk-off grand slam to left field. A humbled Aspromonte averred that he could not have done this on his own, that he had help coming from somewhere.11

On July 26 Billy Bradley was in Houston again to see Dr. Girard. Once again he met with Aspromonte and once again he requested a home run. Aspro was homerless since the grand slam, and his hitting had deteriorated even further to .176 over his last 20 games. This time Aspro told Billy he was pushing his luck and suggested instead that Billy settle for a couple of base hits.

By this time Billy’s eyesight had been partially restored and he was able to watch the game at Colt Stadium. Tracy Stallard of the Mets had loaded the bases with Al Spangler, Rusty Staub, and Jimmy Wynn when Aspromonte came to bat in the bottom of the first. Astonishing even himself, Aspro once again hit a grand slam.12

Houston broadcaster Gene Elston was aware of the human-interest story involving Billy Bradley and referred to it on the air. The game was interrupted to retrieve the ball and Aspromonte and Bradley hugged. A New York sportswriter asked Aspromonte, “Are you doing it for the boy, or is the boy doing it for you?” Aspro replied, “It’s almost spooky, isn’t it? But if Bill will stick around, I’ll be tempted to buy him a season ticket. It’s a great thrill to see how happy it makes the boy.”13

After the 1963 season, Aspromonte undertook a series of eight rigorous daily 90-minute isometric exercises in his Brooklyn home to strengthen the “worn out” lumbar disc in his lower back. At times the pain was severe enough to prevent him from bending down. After the offseason of rest and exercises, the acute pain from which he suffered in 1963 had largely been eliminated.14

Indeed, Aspromonte recovered to have one of his best seasons in 1964. His slash line over 608 plate appearances in 157 games was .280/.329/.392. He set career highs with 69 RBIs and 12 home runs, including two more grand slams. He led the Colt .45s with a .280 batting average, and he had a .973 fielding percentage, still (as of 2018) a record for Houston third basemen, and a National League record at that time.15 In 1964 the Colt .45s duplicated their 1963 record of 66-96 and their ninth-place finish, but the resurgent Bob Aspromonte with a 66-point gain in batting average trailed only the 70-point gain by teammate Bob Lillis as the National League’s most improved hitters.16

The Houston Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America voted Aspromonte as the team’s Most Valuable Player for 1964. Although both the Reds and Dodgers sought him in a trade, Vivian Smith, wife of co-owner Bob Smith, put the kibosh on any trade talk for Aspromonte.17

In 1965, the club abandoned Colt Stadium, moving into a space-age sports facility. Officially known as the Harris County Domed Stadium, the venue quickly became known as the Astrodome as the team was rechristened the Astros. Lum Harris was now the manager and by season’s end, Bob Smith would sell his share of the club to Roy Hofheinz.

On April 9, 1965, a crowd of 47,879 watched Mickey Mantle hit the first home run in the inaugural exhibition game in the Astrodome as the American League champion New York Yankees suffered a 2-1, 12-inning exhibition loss to the nascent Astros. Three days later, the Astros hosted the Philadelphia Phillies in the first official game at the Dome. Aspromonte caught the ceremonial first pitch from astronaut Alan Shepard.18 Aspro managed one infield single in four at-bats in a 2-0 loss to Philadelphia. After an eight-day road trip that ended with a win, the Astros set a team record by embarking on a 10-game winning streak including nine at home. Aspromonte expressed great satisfaction from contributing 11 game-winning hits to the Astros cause in 1965.19

After winning 12 of their first 18, the Astros soon plummeted to familiar territory, ninth place, with a record of 65-97. Though Aspromonte’s slash line was a respectable .263/.310 in 152 games, he managed only five home runs and 52 RBIs in the pitcher-friendly confines of “the Eighth Wonder of the World.” Early in the year, he received an encouraging letter from Billy Bradley. Following his surgeries, Billy’s eyesight recovered. With the help of corrective lenses, Billy resumed playing baseball. The letter contained a newspaper article with a note that read, “This one’s for you, Bob. I didn’t hit you a home run, but I pitched you a no-hitter.”20

Roy Hofheinz fired both manager Lum Harris and general manager Paul Richards after the 1965 season. Under new manager Grady Hatton, the Astros improved to eighth place in 1966, with a record of 72-90. Aspromonte’s solid fielding continued, with a National League-leading .962 for third basemen. His batting tapered to .252/.297 with 52 RBIs and 8 home runs, but he added two more grand slams to his final career total of six, a Houston record that stood until July 25, 2011, when Carlos Lee hit his seventh grand slam in an Astros uniform.21

In 1967 Aspromonte enjoyed his finest year in a Houston uniform. He set career highs with 24 doubles and a .294/.354/.401 slash line in 137 games. Along with 6 home runs and 58 RBIs, he matched his 1963 high of five triples. The Astros announced that H.B. “Spec” Richardson was the new general manager on July 27 in midst of a ninth-place, 69-93 campaign.

Aspro’s playing time began to diminish in 1968 as young third baseman Doug Rader was being groomed for the position. Even so, Aspromonte participated in yet another historic event on April 15, 1968. Astros ace Don Wilson and Tom Seaver of the Mets locked horns in a tremendous duel that contributed to a record that has lasted half a century. Seaver was pitching a two-hit shutout when he was pulled from the game after 10 innings. Wilson, meanwhile, pitched a shutout of his own through nine. Then the bullpens took over, holding the stalemate for what amounted to almost another two full games. When the Astros came to bat in the bottom of the 24th inning, the score was still deadlocked at 0-0. Norm Miller singled off pitcher Les Rohr, Jim Wynn was walked intentionally, Rusty Staub grounded out, and John Bateman was intentionally walked, when Aspromonte came to the plate.

Aspro was 0-for-8 with one walk. Still adept at making contact, he laced a grounder to short that Al Weis failed to handle cleanly, allowing Miller to score the winning run. Bob Aspromonte had a walk-off E-6, and the Astros defeated the Mets 1-0 in what remains as of 2018 the longest reciprocal shutout by two major-league teams.22

By 1968, America had entered one of the most turbulent periods in its history. Civil unrest began to offset the promise of Camelot and the Great Society. On June 6, only two months after Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy was shot and killed in Los Angeles.

President Lyndon B. Johnson declared June 9, the day after Kennedy’s funeral, as a national day of mourning. Baseball Commissioner William Eckert ordered that no games on June 8 should start until after the burial, and that while games would continue on June 9, Eckert proclaimed that any player could “pay respects” if desired by sitting out to observe the day of mourning.23

Despite the option given the players by the commissioner, players who opted out were threatened with consequences. The Astros were scheduled to host the Pirates as Aspromonte, Staub, player representative Dave Giusti, and Pittsburgh’s Maury Wills all opted not to play. Giusti noted that the entire team voted to abstain, but rescinded amid a threat of “very definite economic pressures” from GM Richardson.24 A question of team retaliation for Aspro’s stance on the Robert Kennedy matter arose. His playing time continued to decrease, and with it came a decline in production. His 1968 slash line fell to .225/.285/.284.

Perhaps hard feelings lingered over these June events. Giusti was traded to St. Louis. Staub was soon traded to Montreal. By 1968, Bob Aspromonte was the only remaining member of the original 1962 Colt .45s still with the franchise. One of the team’s most popular players in its short history, Aspro was their second drafted player, their first-ever batter and position player, and the last player from the team’s first Opening Day lineup. On December 4 that player was gone, traded to the Atlanta Braves for Marty Martinez.

With Paul Richards as the Braves’ general manager and Lum Harris their manager, Aspromonte was not the first Houston alumnus to find his way to Atlanta. He was reunited with former teammates Sonny Jackson, Ken Johnson, and Claude Raymond in the Braves’ fourth season in Georgia. The 1969 season also marked the first in the divisional era. Both the American and National Leagues had realigned to each form two divisions, East and West, of six teams apiece. Atlanta and Houston found themselves in the National League West.

Since Clete Boyer was the Braves’ regular third baseman, Bob Aspromonte became a part-time player, filling in in left field, third base, second base, and shortstop. His slash line was .253/.304/.348 in 215 plate appearances with 3 home runs and 24 RBIs. Every National League West team except San Diego factored into the pennant race and as late as September 10, Aspro’s former team was two games out of first with a record of 75-65. But the Astros declined after that to finish at exactly .500, while Aspro’s new team won the first-ever National League West Division title with a record of 93-69.

The 1969 National League Championship Series marked Aspromonte’s first and only postseason experience. The Braves’ opponents were the unlikely New York Mets. Having lost at least 89 games and finished no higher than ninth place in their first seven seasons, little was expected from the Mets in 1969. As late as May 27, the Mets won-lost record stood at 18-23. However, they soon caught fire and by August, they passed the Chicago Cubs to finish at 100-62.

Aspromonte’s postseason experience was limited to three pinch-hit appearances and no action in the field. In Game One, in Atlanta, he grounded out for Phil Niekro in the eighth inning as Tom Seaver picked up a 9-5 decision. Aspro was again sent in as a pinch-hitter in Game Two, in Atlanta. Batting for Cecil Upshaw, he popped up in the eighth inning. With Ron Taylor taking the 11-6 victory, the Braves faced elimination as the series headed to New York. Aspromonte once again pinch-hit for Upshaw, this time facing Nolan Ryan to lead off the ninth inning. The young flamethrower retired Aspro on a pop fly. Two outs later, the Mets had swept the Braves and went on to face the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

In 62 games as a reserve player in 1970, most of Aspromonte’s time in the field was spent at third base, with a few games at shortstop, left field, and first base. In 142 plate appearances, his slash line was .213/.282/.236 with no home runs and 7 RBIs. Atlanta fell to a 76-86 record and a fifth-place finish in the National League West.

Aspro had maintained a friendly connection with Gil Hodges during the decade since they were teammates with the Dodgers. After Joe Foy‘s disappointing campaign in 1970, the Mets were in the market to upgrade at third base. Hodges turned toward his former teammate, and Aspromonte was happy to play for his old friend and mentor. Having left Foy unprotected, the Mets lost him to the Washington Senators in the Rule 5 Draft. Meanwhile, the Mets traded pitcher Ron Herbel to Atlanta for Aspromonte. Aspro had worn number 14 for his entire career to honor Hodges, and this became the basis of some good-humored teasing when Aspromonte told Hodges he wanted to wear the number for the Mets. Hodges was not surrendering 14, and he assigned Aspro number 2.25

Aspromonte was given a renewed opportunity as a starter in 1971 as Hodges penciled him into the Opening Day lineup at third base, his eighth and final Opening Day start. After a slow beginning, Aspro peaked on May 18 with a 3-for-4 outing against former Atlanta teammate Mike McQueen that included two solo home runs, bringing his batting average to .283. He was still hitting a respectable .270 in June when a calf muscle injury interrupted his momentum. Aspro was limited to 38 games in the second half of the season and was unable to sustain his prior level of performance.

On September 25, Aspromonte pinch-hit for left fielder Dave Marshall in the bottom of the 15th inning to score Tim Foli from second base with the game-winning run. The walk-off proved to be Aspro’s final hit, in his next to last major-league game. His last appearance took place on September 28 when he started at third base. Hitless in three official at-bats, Aspro drove in his final run when Cleon Jones scored on his sacrifice fly in a 5-2 loss to the Cardinals and Steve Carlton. Aspromonte’s 1971 slash line was .225/.285/.301 in 104 games, with 5 home runs and 33 RBIs.

The Mets finished a disappointing 1971 season with a record of 83-79, tied for third place with the Cubs. Needing to upgrade at third base again for 1972, the Mets traded Nolan Ryan to the California Angels for Jim Fregosi, releasing Aspromonte. Sparky Anderson still thought Aspro could play and invited him to spring training with the Reds in 1972. Although Aspromonte was featured on a 1972 Topps card with Cincinnati, he failed to make the team and hung up his spikes.26

Aspro’s final career slash line was .252/.308/.336. He finished with 1,103 hits and 60 home runs. The disciplined hitter’s strikeout totals in his eight seasons as a regular ranged from 44 to 63, topping 60 only once. By contrast, 20 major-league players had 60 or more strikeouts in the first two months of the 2018 season.

After retiring as a player, Aspro decided to make Houston his year-round home, ultimately persuading both of his brothers to join him. They formed a partnership to obtain a Coors distributorship in 1975, which they named Aspromonte-Coors Distributing Company.27

Bob Aspromonte managed the distributorship, which by 1981 was valued in the range of eight figures. He implemented several innovative business strategies that improved both company profitability and personnel loyalty and morale. He ran Aspromonte-Coors until 2000, when he sold his majority interest. Aspromonte remained active in the Houston community, lending his name to the YMCA, the Lions Eye Bank Foundation, and Houston Eye Associates.

There is an epilogue to the Bill Bradley story. In 2003 Aspromonte was blinded in one eye after a car battery exploded in his face. When Bradley, now 51, learned of the injury, he contacted Aspro to offer support. The same ophthalmologist who restored Bradley’s sight, Dr. Louis Girard, operated on Aspromonte and eventually helped him to overcome substantial damage to his eye.28

Aspromonte remained a revered figure throughout the Houston community. He said he was particularly proud of receiving the Ellis Island Medal of Honor, a humanitarian award honoring American diversity and fostering tolerance, respect, and understanding among religious and ethnic groups.29

In 2005 Aspro was inducted into the Texas Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2011, Bob and Ken were both elected to the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in Chicago. For the silver anniversary of the franchise in 2012, the Astros created a Walk of Fame outside Minute Maid Park. Their first honoree was Bob Aspromonte: “Aspro the Astro.” And on April 10, 2012, the 50th anniversary of the franchise’s first game, Aspromonte threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Away from the game, he retained a powerful reverence for the bond of family, which includes his brothers along with three generations of nieces and nephews.30

“In all my years in baseball,” remarked fellow Houston baseball legend Larry Dierker, “I have never known a player with more class than Bob Aspromonte.”31

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Thanks for assistance to Bob Aspromonte, Mark Kanter, Maxwell Kates, and Liubov Wernick.

Notes

1 Author interview with Bob Aspromonte, February 24, 2018. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations or unattributed memories come from this interview.

2 Interview with Bob Aspromonte, February 24, 2018.

3 Joe Reichler and Budd Theobald, “Bob Aspromonte” in Here Come the Colts (New York: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1962), 10.

4 Ibid. Cockroach, “From Brooklyn to the Bayou City: Bob Aspromonte” on Astros County: Your Neighborhood Astros Blog and Grill, January 27, 2017, astroscounty.com; accessed June 3, 2018.

5 Cockroach.

6 Interview with Bob Aspromonte, February 24, 2018.

7 Robert Reed, A Six-Gun Salute: An Illustrated History of the Houston Colt .45s, 1962-1964 (Houston: Lone Star Books, 1999), 59.

8 Bill Brown and Mike Acosta, Deep in the Heart: Blazing a Trail from Expansion to World Series (Houston: Bright Sky Press, 2013), 29.

9 Brown, 31.

10 Ibid.

11 Reed, 124.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Mickey Herskowitz, “Aspromonte Leaves Drydock — Worn-Out Back Disc Repaired,” The Sporting News, February 1, 1964: 23.

15 Cockroach.

16 Chuck Pickard, “Colts’ Lillis Boosted Bat Mark 70 Points — Majors’ Best Gain,” The Sporting News, November 7, 1964: 25.

17 Clark Nealon, “Houston Picks MVP — Aspro the Astro,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1965: 7.

18 Cockroach.

19 Interview with Bob Aspromonte, February 24, 2018.

20 Reed, 124.

21 Brown, 30.

22 Norm Miller, To All My Friends … from Norm Who? (Houston: Double Play Productions, 2009), i.

23 Cockroach.

24 Associated Press, “Houston’s Staub, Aspro Don’t Play,” Dallas Morning News, June 10, 1968: 2.

25 “National League Rosters, Uniform Numbers, ” The Sporting News, April 17, 1971: 38.

26 1972 Topps #659, Brooklyn: Topps Chewing Gum Inc., 1972.

27 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, “Bob Aspromonte” in Aaron to Zuverink, (New York: Avon Books, 1984), 16.

28 Brown, 31.

29 neco.org/medal-of-honor.

30 Interview with Bob Aspromonte, February 24, 2018.

31 Mickey Herskowitz, “Players Don’t Come Classier Than Aspromonte,” Houston Chronicle, February 14, 2001.

Full Name

Robert Thomas Aspromonte

Born

June 19, 1938 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.