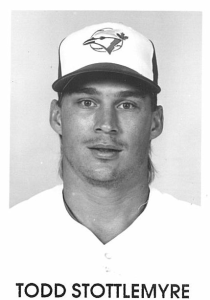

Todd Stottlemyre

Life has its defining moments. For many ballplayers, the remembered moments come from first appearances to championship wins and include everything in between. But the life of a ballplayer is often defined by moments off the playing field and away from the crowds. A defining moment in the life of young Todd Stottlemyre came when he was only 15 years old. It took place in a hospital room. The opposition that day was a lifelong enemy of the Stottlemyre family – leukemia. Todd gave his younger brother, Jason, a bone-marrow transplant. The procedure was painful for Todd. Jason was 11 years old and had been diagnosed in 1977, four years before the procedure. On March 3, 1981, within days of the procedure, Jason died.

“I suppose we expected it to happen, but I can’t say we were prepared for it. Now I take him every day to the field with me. And if something bad happens to me out there, well, it doesn’t mean so much.”1

And fully coming to grips with the loss of his younger brother would take some time.

Todd Vernon Stottlemyre was born on May 20, 1965, in Sunnyside, Washington, a small city near Yakima in the south central part of the state. He was the second of three sons born to Mel and Jean Stottlemyre. His father was in his second season with the New York Yankees. His older brother, Mel Jr., had been born two years earlier. Jason came along in 1969.

Growing up, Todd was primarily an infielder. He took to the mound, for the first time since Little League, while playing American Legion baseball. In the summer between his junior and senior years, he enjoyed much success and hurled a two-hitter in shutting out Moorhead, Minnesota, in the semifinals of the regional tournament in Miles City, Montana.2

Todd graduated from Davis High School in Yakima, where in his senior year he started the season with an 8-0 record, a 0.53 ERA, and 87 strikeouts in 54 innings.3 His record, and his being the son of an accomplished big-league pitcher and coach, attracted attention. Shortly after graduating from high school, he was drafted by the Yankees in the fifth round of the June amateur draft in 1983 but did not sign.

He went on to the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. In his freshman year at UNLV, he went 10-4 with a 4.20 ERA and 91 strikeouts in 105 innings.4 He hurled a one-hitter on March 19, 1984, to defeat Nebraska, 2-1. He was selected for Team USA’s 43-man roster on May 3, 1984 but was not selected for the Olympic team. Todd and his brother Mel Jr. withdrew from UNLV after Todd’s freshman year, as their father thought they were being overworked by the UNLV head coach. They were both eligible for the draft in January 1985.5 Todd was made the overall number-one pick in the draft’s secondary phase (for previously drafted players) and was selected by the Cardinals. Brother Mel Jr. was drafted third overall and was the first choice of the Astros.

Todd, while negotiating with the Cardinals, transferred to Yakima Community College, where he pitched in the spring of 1985. He was unable to come to terms with St. Louis, and Toronto in June 1985 staked its claim, making him their number-one pick in the draft. He signed with the Blue Jays on August 12, 1985.

Stottlemyre’s first pitch as a professional was thrown in the Florida Instructional League in the autumn of 1985. He was assigned to the Class-A Ventura County Gulls of the California League at the beginning of the 1986 season. With Ventura he was 9-4 with a 2.43 ERA before being promoted in June to the Knoxville Blue Jays of the Double-A Southern League. In his best game with Knoxville, on June 30 he had a no-hitter against Jacksonville through seven innings but had thrown 100 pitches. His manager, Larry Hardy, pulled him from the game.6 The win in that game brought Stottlemyre’s early record with Knoxville to 3-0 (0.42 ERA). He wound up posting an 8-7 record (4.18 ERA) with Knoxville.

He went to spring training with Toronto in 1987 and was assigned to Triple-A Syracuse. He went 11-13 (4.44 ERA) in 34 starts with the Chiefs. He started the 1988 season with Toronto. In his fourth start, on May 3, he flirted with a no-hitter. He took a perfect game into the seventh inning. With one out in the bottom of the seventh, and the Blue Jays leading the game, 3-0, Stottlemyre hit Rey Quinones with a pitch. He recorded one more out that inning before losing the no-hitter and shutout on a double by Alvin Davis that scored Quinones. At that point, manager Jimy Williams removed him from the game. The Blue Jays pulled away in the late innings for a 9-2 win, and Stottlemyre had his first major-league victory.

However, through 23 appearances, Stottlemyre was 3-8 with a 5.36 ERA. He was sent back to Syracuse and in one month with the Chiefs, he was 5-0 (2.05 ERA). He rejoined the Blue Jays in September, and the 23-year-old right-hander finished his first big-league season with a 4-8 record in 28 appearances. The Blue Jays finished third in the AL East.

In 1989 Stottlemyre got off to a rocky start and was 0-3 (5.81 ERA) when he was once again dispatched to Syracuse. He was there from May 15 through the end of June, appearing in 10 games and going 3-2 (3.23 ERA). In July he returned to the major leagues to stay. The big difference in 1989 was that Stottlemyre had, during the offseason, developed a slider. By the time he returned to the Blue Jays, he was making good use of the pitch. During the balance of the 1989 season, he was 7-4 with a 3.38 ERA as the Blue Jays finished first in the AL East. Stottlemyre got his first taste of postseason play. The Blue Jays lost the best-of-seven ALCS to Oakland in five games. Todd started Game Two and was charged with the loss as Toronto lost to the A’s, 6-3.

“It was the most frustrating time of my career. I wondered if I would ever come back as a Jay, or somewhere else.” – Todd Stottlemyre, in April 1990, reflecting on being sent down in 1989 and coming back to have success.7

While in the minors in 1989, Stottlemyre had been mentored by Syracuse pitching coach Galen Cisco, who joined him with Toronto in 1990. Cisco had told him, “You have to work on your concentration, your intensity, and controlling your emotions.” The hard work, which included Todd being the first to report for spring training in 1990, paid off.8

Manager Cito Gaston, who had sent Stottlemyre to the minors in 1989, handed him the ball on Opening Day in 1990. Although he lost the opener to Texas, 4-2, he put together a string of four straight wins in the early going, topped off by his first complete game of the season, a 5-1 win over Detroit.

“This ballpark was my playground and backyard. It was my fantasyland.” – Todd Stottlemyre discussing Yankee Stadium on June 15, 1990.9

On Father’s Day 1989, Stottlemyre made his first career appearance at Yankee Stadium, where his father had hurled for the Yankees. He defeated the Yankees, 8-1, in his second complete-game win of the season and just missed a shutout when Matt Nokes homered with two outs in the ninth inning.

Toronto was in contention in 1990 and finished in second place. Stottlemyre, after beginning the season 9-7, was 13-17 with a 4.34 ERA. He led the Blue Jays staff with four complete games. The next season, he won his first five decisions, and was undefeated at home (6-0) until August 10. He wound up with a season’s record of 15-8 and was the staff leader in innings pitched (219) as the Blue Jays won their second division title in three years. In the postseason, Toronto lost the League Championship Series to Minnesota in five games. Stottlemyre started Game Four and was on the short end of a 9-3 decision. The Twins had reached him for four fourth-inning runs, and he came out of the game with two outs in the inning, trailing 4-1.

In 1992, after knocking at the door for five seasons, Toronto earned the first World Series trophy in the 16-year history of the franchise. Stottlemyre was 12-11 with a less-than-stellar ERA of 4.50, but his season had more than its share of highlights. On April 29, pitching at home against the Angels, he had his first career shutout, scattering seven hits in a 1-0 win. His second shutout, on August 26 at Chicago, put Toronto up by two games as the season entered its last 30 contests. As often happened in 1992, the Toronto bats came through with Stottlemyre on the mound. The score on August 26 was 9-0.

In postseason play in 1992, Todd was moved to the bullpen and made five appearances. In Game Four of the ALCS against Oakland, he entered with one out in the bottom of the fourth inning. Starter Jack Morris had been ineffective, and the A’s had built up a 5-1 lead. Runners were at the corners. Stottlemyre left the game after pitching the seventh inning. Toronto scored three runs in the top of the eighth to cut Oakland’s lead to 6-4. Mike Timlin came on to pitch for Toronto in the bottom of the eighth. A homer by Roberto Alomar tied things up in the ninth inning, and Toronto won, 7-6, in 11 innings. The Blue Jays took a 3-1 series lead and won in six games.

In the 1992 World Series, Toronto faced Atlanta. Stottlemyre appeared in four games, pitching a total of 3⅔ innings of scoreless ball. His Game One entrance marked the second time that a father-son pitching combo had made World Series appearances. Jim Bagby (1920) and Jim Bagby Jr. (1946) had preceded Mel and Todd. In the Game Six win that clinched the championship for Toronto, Stottlemyre was called on at the beginning of the seventh inning. Toronto was leading 2-1. After striking out Mark Lemke and inducing Jeff Treadway to ground out, he allowed an infield hit to Otis Nixon. At that point, with left-hand-hitting Deion Sanders due up, manager Cito Gaston brought in David Wells to replace Stottlemyre. There was no scoring in the inning, but Atlanta tied the game in the ninth inning. Toronto went on to win the game, 4-3, in 11 innings.

In 1993, as the Blue Jays won their second consecutive World Series championship, Stottlemyre was 11-12 with a 4.84 ERA. The highlight of his season was a shutout of the Boston Red Sox on September 21. He struck out 10 and walked only one batter in the 5-0 win. The win extended Toronto’s division lead to five games. The Blue Jays wound up winning the division by seven games. Although his team was successful during the postseason, Stottlemyre did not do well in either the ALCS or the World Series. In Game Four of the ALCS against the White Sox, he allowed five runs, including a monster homer by Frank Thomas, in six innings of work and was charged with the loss as Toronto fell, 7-4. In Game Four of the World Series against the Phillies, he was pulled after allowing six runs in the first two innings of a slugfest that was ultimately won by Toronto, 15-14.

But at a time in his life when Stottlemyre should have felt fulfilled, the demons that had been with him since the death of his brother still haunted him. As a pitcher, despite an increasing repertoire of pitches, he still tried to overpower everyone. As a person, he could be temperamental. He saw himself as the “murderer” of his little brother, as he had been the transplant donor.10

Stottlemyre let his temper get the better of him after the World Series. During the Series, Mayor Ed Rendell of Philadelphia, remembering the long homer hit by Frank Thomas in the ACLS against Stottlemyre, said, “I’d like to hit against him.” After the Blue Jays won the World Series, there was a parade followed by a rally at the Toronto SkyDome. Stottlemyre stepped to the microphone and said, “Well, I’ve got one message for the mayor of Philly, he can kiss my ass.”11 Stottlemyre’s emotions had gotten the best of him, and he was noticeably out of control.

He sought guidance from Harvey Dorfman, a noted mental skills coach. Dorfman was able to enable Stottlemyre to cope with his guilt and to address his challenges. Dorfman advised Stottlemyre not to have a knee-jerk reaction when faced with a problem – to be less confrontational. He had not always been successful in handling confrontations, but he was now better equipped to deal with them.12

It was during spring training of 1994 that Stottlemyre was confronted with a challenge that tested the behavioral standards he had learned from Dorfman. He was with mentor and teammate Dave Stewart, a fellow pitcher. On February 19 they and a few guests had been out to dinner in Tampa to celebrate Stewart’s 37th birthday. After dinner, as the clocked passed midnight, the group went to the Masquerades Nightclub. Stottlemyre and several of the guests entered, but Stewart was detained by police officers. In short order, Stottlemyre was also detained. In the process, he was brutalized by the officers and thrown in the back of a police cruiser. He successfully resisted the urge to retaliate.

What provoked the incident? Stewart refused to pay a $3 cover fee and did not want to wear a wristband (indicating he was old enough to drink) when entering the bar. A security person named Steve Bell called the police, and the police, 14 in number, overreacted. Stewart and Stottlemyre were arrested and accused of attacking the police. The local media portrayed Stottlemyre and Stewart as criminals. A trial date was set for after the season, and throughout the season there was a cloud over Stottlemyre. Throughout the ordeal, the players maintained their innocence.13

After the 1994 season, in which he was 7-7 with a 4.22 ERA before it ended with a player strike in August, Stottlemyre had his day in court. The trial took place in November. The testimony from the police, according to Stottlemyre, was fabricated and, per accounts of trial observers, inconsistent with accounts given in depositions during pretrial hearings and investigations.14 On November 10 Stottlemyre testified and spoke of the abuse he suffered in February. At the end of the trial, the jury came to the realization that the police had been lying and found Stottlemyre and Stewart not guilty on all counts.15 One week after the trial began, it had taken the jury 45 minutes to deliberate as to the outcome.16

It was then back to baseball. Stottlemyre had become a free agent and signed with the Oakland Athletics.

With the A’s in 1995, Stottlemyre was 14-7 and finished second in the American League with 205 strikeouts. The good news was that he led the staff in wins. The bad news was that when the top pitcher on the staff wins only 14 games, you are in trouble. The A’s were 67-77 for the strike-shortened season and finished in fourth (last) place. The pitching staff was in chaos: 23 men had pitched for the A’s during the 1995 season. Seven of the pitchers were 30 or older. In the offseason, the A’s went for youth and dealt the 30-year-old Stottlemyre to the St. Louis Cardinals for four unknown players.

With the Cardinals in 1996, Stottlemyre went 14-11 and brought his ERA down to 3.87 in a career-high 223⅓ innings. His turnaround was due in large part to the mentorship of Dave Duncan. Of course, he always had another mentor closer to home, his father.

On September 3 Stottlemyre was the winning pitcher as the Cardinals defeated Houston, 12-3. Over eight innings, he scattered four hits and struck out nine batters, bringing his record for the season to 12-10. The win put the Cardinals a half-game ahead of Houston. It also was Stottlemyre’s 95th career win. That was significant: Combined with his father’s 164 wins, it made Mel and Todd the winningest father-son pitching combo in major-league history. Their 259 wins eclipsed the record previously held by Dizzy and Steve Trout. (When Todd retired at the end of the 2002 season, their record mark stood at 302 wins.)

The win on September 3 was the fifth straight for the Cardinals. By the time that streak ended on September 8, they had won eight in a row. They extended their division lead down the stretch. After Stottlemyre earned his 14th win on September 23, St. Louis led the division by 5½ games. The magic number was one. They clinched the division the next night, and advanced to postseason play.

It was Stottlemyre’s fifth postseason. In the opening game of the Division Series against the Padres, he earned his first postseason win. He pitched into the seventh inning, allowing only one run, a homer by Rickey Henderson. He struck out seven batters and left the game with a 3-1 lead, which wound up being the final score.

In the LCS against Atlanta, Stottlemyre was the winner in Game Two. He pitched six innings as the Cardinals won 8-3 to take a 2-0 lead in the series. Duncan noted after the game that Stottlemyre’s new-found maturity was a key factor in the win. “The old Todd wouldn’t have known himself well enough to back off (after issuing a two-run third-inning home run to Marquis Grissom that cut the Cardinals’ lead to 3-2). His young mentality was to overpower everybody.”17 Of Duncan, Stottlemyre said, “You lose focus, and he reminds you (to take it one pitch at a time). It sounds so simple but it’s tough sometimes. He gives you a game plan. His preparation is unbelievable.”18

The Braves came back and won the series in seven games. Stottlemyre absorbed the loss in Game Five when the Braves feasted on the offerings of five Cardinals pitchers in a 14-0 blowout. Todd lasted three batters into the second inning and was charged with seven runs. His final appearance in 1996 came in Game Six against Atlanta. He entered the game in the bottom of the eighth inning with the Cardinals trailing 2-1. He allowed Atlanta an additional run as the Braves won, 3-1, to even the series at three games apiece.

In 1997 Stottlemyre went 12-9 (3.88 ERA) in his second year with the Cardinals, tying for the team lead in wins, but St. Louis was out of the running early that season, finishing in fourth place with a 73-89 record. In 1998, with free agency looming, the Cardinals elected to trade Stottlemyre to the Texas Rangers on July 31 after he had gone 9-9 (3.51 ERA) in 23 appearances. He went to the Rangers with shortstop Royce Clayton for third baseman Fernando Tatis and pitcher Darren Oliver. With the Rangers, he was 5-4 (4.33 ERA) as his temporary employers finished first in the AL West. In the postseason opener, Stottlemyre pitched a complete game, but was the losing pitcher as the Yankees, with his pitching-coach father in the dugout, defeated the Rangers, 2-0, to go one up in the Division Series. New York swept the best-of-five series.

A free agent after the season, Stottlemyre signed a four-year contract with Arizona worth $32 million. In 1999, his first year with the pitching-rich Diamondbacks, he started 17 games and went 6-3. For the first time in his career, he spent a prolonged amount of time on the disabled list with a torn rotator cuff. He had come out of a May 17 contest at San Francisco after four innings. It was obvious to his manager, Buck Showalter, that something was wrong.

Generally, season-ending surgery is the prescription for a rotator cuff tear, but Stottlemyre opted to not throw for a month and to engage in an exercise program that would strengthen his arm and body. During his recuperation, he addressed problems with his delivery that had put undue stress on the shoulder. His hope was to return to action late in the season. With surgery, he would not have returned until the beginning of the 2001 season.

“Next thing I know, there was a team standing there with cameras and baseballs. I didn’t know what was going on.” – Todd Stottlemyre, August 5, 199919

Stottlemyre made his first rehab start on August 4 with the Diamondbacks entry in the Arizona Rookie League. Before the game he was into his well-known pregame ritual. He did not communicate with anyone, bringing his intensity to a peak level, focusing total anger on his opponent, albeit a group of very young minor-league players. The team was known as the Mexican Stars. The team was unaffiliated, and its players interrupted Stottlemyre to hug him and take pictures – not quite the norm.

After the disruption, Stottlemyre took to the mound and threw 58 pitches in four shutout innings, yielding three hits and striking out five batters. His fastball was clocked at 91 mph. He had two more rehab appearances and returned to the Diamondbacks on August 20.

Down the stretch, Stottlemyre was 2-2. The Diamondbacks easily won the AL West, outdistancing second-place San Francisco by 14 games. Arizona faced the Mets in the Division Series and Stottlemyre started Game Two. In six innings, he allowed one run, and the Diamondbacks had a 5-1 lead. He came out of the game with one out in the seventh inning and the bullpen maintained the lead. Arizona won the game, 7-1, and evened the series at one game apiece. The Mets won the next two games and proceeded to the LCS.

In 2000 Stottlemyre once again spent a major part of the season on the DL. Suffering from tendinitis in his pitching elbow, he was shut down in late June after coming out of a game on June 25 when he hurled only one inning against the Rockies. The inflammation in his elbow had pushed against his ulnar nerve, causing discomfort through his forearm.20He did not pitch again until September 3.

Not only was the 2000 season fraught with physical challenges, but there were emotional challenges as well. Stottlemyre and his wife, Sheri, had been married for 10 years but were in the process of getting a divorce. They had one child, a daughter, Rachel, born in 1996.21

For the 2000 season, Stottlemyre went 9-6 with a 4.91 ERA. The Diamondbacks finished third in the NL West. In September, Stottlemyre had nerve-repositioning surgery on his elbow and missed the 2001 season.

On November 17, 2000, Stottlemyre received the Branch Rickey Award. The award, presented by the Rotary Club of Denver, cited Stottlemyre for his community service, including his longtime efforts to raise funds for leukemia research. Along with his father and brother, he had also hosted a golf tournament in Las Vegas to raise funds for the Make-a-Wish Foundation.22

Stottlemyre never was quite 100 percent again, experiencing pain in his shoulder and elbow. He was on the sidelines as the Diamondbacks won the 2001 World Series, and pitched in only five games in 2002, going 0-2.

Stottlemyre retired as a player after that season, having posted a 138-121 record in 372 games, 339 as a starter. His career ERA was 4.28. His 25 complete games included six shutouts.

Since retiring as a player, Stottlemyre has pursued a successful career as a financial adviser. In 1999 he had come to a crossroads in his life when his father was hospitalized with cancer. Mel Sr. survived that battle but ultimately succumbed to the disease in 2019. In recent years Stottlemyre has directed his energies to advising people on how to better live their lives and achieve not only financial but emotional fulfillment. He has authored two books, the first of which was Relentless Success, published in 2017. A novel, The Observer, was published late in 2020.

In 2021 Todd’s brother Mel Jr. was diagnosed with prostate cancer two months after the second anniversary of the death of Mel Sr., and the family came together for another battle.

Stottlemyre has five children and in 2022 lived with his wife, Erica, and their family in Phoenix, Arizona.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com. and the following:

Blackwell, Mike. “Stottlemyres Put Pros on Hold, Form Heart of Rebel Pitching Staff,” Austin American-Statesman, May 25, 1984: F6.

Lang, Jack. “Baseball Free-Agent Draft Is a Father & Son Affair,” The Sporting News, January 21, 1985: 44.

MacCarl, Neil. “Stottlemyre Tries Again,” The Sporting News, March 27, 1989: 30.

Packet, John. “Another Up-and-Coming Stottlemyre Passes Through,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, April 12, 1987: D-5.

Pearlman, Jeff. “Against All Odds Diamondbacks Righthander Todd Stottlemyre Is Trying to do What No One Before Him Has Ever Done: Pitch Effectively with a Torn Rotator Cuff,” Sports Illustrated, February 28, 2000.

Pepe, Phil. “Class, Courage Fit Stottlemyre,” New York Daily News, March 16, 1981: 54.

Poliquin, Bud. “Stottlemyre Grows into His Fine Name,” Syracuse Herald American, April 12, 1987: D1

Notes

1 Peter Richmond, “Blue Jays’ Stottlemyre Now Has ‘The Look,’” Seattle Times, March 22, 1987: C3.

2 “Yakima Wins Miller Title,” Billings (Montana) Gazette, July 13, 1982: 5-B.

3 Kevin Taylor, “On the Diamond, Area Teams Are Seeking a Gem,” Spokane Chronicle, May 26, 1983: 33.

4 “Stottlemyre Brothers Picked 1st, 3rd in Free-Agent Draft,” Seattle Times, January 9, 1985: F2.

5 Chris Mortensen, “Expos Show Interest in Benedict,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, January 6, 1985: C-14.

6 “Stottlemyre Just Ran Out of Pitches,” Toronto Star, July 3, 1986: F3.

7 “Stottlemyre Starts Opener for Jays,” The Sporting News, April 16, 1990: 20-21.

8 “Stottlemyre Starts Opener for Jays.”

9 “Jays Don’t Feel at Home in the Dome,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1990: 12-13.

10 Rick Hummel, “For a Long Time, Stottlemyre Felt He ‘Was the Murderer of My Little Brother,’” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 23, 2020.

11 Joe Weinert, “Blue Jay Victory in World Series Brings Out Mob,” Atlantic City Press, October 25, 1993: D1.

12 Hummel.

13 Rosie DiManno, “Baseball Stars and Tampa Police in Volatile Mix,” Toronto Star, November 9, 1994: A5.

14 Rosie DiManno, “Bug-Ridden Jury Typical of Weird Trial of Two Jays,” Toronto Star, November 10, 1994: A4.

15 Todd Stottlemyre, Relentless Success: 9-Point System for Major League Achievement (Issaquah, Washington: Made for Success Publishing; 2017).

16 DiManno, “Ex-Jay Pitchers Winners in Court: Stottlemyre and Stewart Acquitted in Just 45 Minutes,” Toronto Star, November 16, 1994: A1.

17 Steve Marantz, “Arm in Arm: The Cardinals-Braves Series Featured Some Outstanding Pitching Because It Featured Some Outstanding Pitching Coaches,” The Sporting News, October 21, 1996: 15-17.

18 Marantz: 17.

19 Ken Brazzle and Chris Walsh, “Stottlemyre Making Quick Recovery,” Tucson Citizen, August 5, 1999: 7-D.

20 “With Stottlemyre Sidelined, Morgan, Daal Must Step Up,” The Sporting News, July 10, 2000: 41.

21 Jack McGruder, “A Special Fan Watches Stottlemyre,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), September 4, 2000: C5.

22 “Todd Stottlemyre Wins Branch Rickey Award,” BusinessWire, September 9, 2000.

Full Name

Todd Vernon Stottlemyre

Born

May 20, 1965 at Sunnyside, WA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.