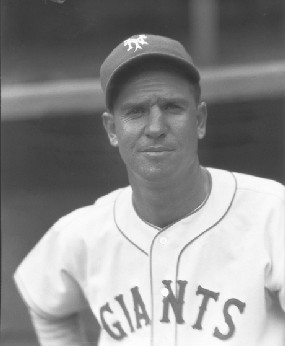

Travis Jackson

During the 1920s and 1930s the New York Giants captured seven National League championships. While they had great outfielders like Mel Ott and Ross Youngs as well as solid pitching, most prominently Carl Hubbell, it was their infield that anchored the team in its success. George Kelly, Fred Lindstrom, and Bill Terry each had a hand in many of the successful Giants campaigns during this era. They, along with several other prominent teammates including Frankie Frisch and Rogers Hornsby, were recognized for their play; each was selected to the Hall of Fame.

During the 1920s and 1930s the New York Giants captured seven National League championships. While they had great outfielders like Mel Ott and Ross Youngs as well as solid pitching, most prominently Carl Hubbell, it was their infield that anchored the team in its success. George Kelly, Fred Lindstrom, and Bill Terry each had a hand in many of the successful Giants campaigns during this era. They, along with several other prominent teammates including Frankie Frisch and Rogers Hornsby, were recognized for their play; each was selected to the Hall of Fame.

Over time, recognition of how the Giants arrived at their success gained a different perspective. It dawned on those invested with selection to the Hall of Fame that these Giants infielders had one factor in common from the early 1920s through the mid-1930s: their shortstop, Travis Jackson. That realization, almost belatedly made, crystallized in 1982 when the Veterans Committee elected Jackson to the Hall. While a solid hitter, Jackson was not in the mold of a Hornsby or Terry, but he was considered by his peers as the defensive anchor for his team and one of the best at his position, if not the best.

Travis Calvin Jackson was born in Waldo, Arkansas, in the southwestern corner of the state, on November 2, 1903. He was the only child of William Jackson, a wholesale grocer, and his wife, Etta. Early news clippings suggest that Travis’s parents named him in honor of William Barrett Travis, hero of the Alamo. [1]

It was from his father that young Travis first gained an interest in baseball. Much attention was focused on him by his parents. In an interview with The Sporting News in 1930, Jackson recalled his early experience with the sport.

“I am an only child, and I guess was spoiled by my parents. Dad played with me a great deal, as dads should do, and our chief sport was baseball. He bought me a hardball when I was three years old and he used to sit in a rocker on the front porch while I sat on the grass in the yard and we’d play catch by the hour.” [2]

Jackson continued his love of the game, playing for the high-school team. His family eventually moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he continued playing. One day he was taken by his uncle to meet Kid Elberfeld, a longtime major leaguer then managing the Southern Association’s Little Rock Travelers. As recounted by Jackson, his uncle introduced him to Elberfeld, extolling his ball playing talents.

“My neffy is quite a player.”

“You don’t say.”

“I do say.”

“Well, Bud, how would you like to go into the clubhouse, put on a uniform, and show me how you play?”

At the offer, the 14-year-old Jackson’s eyes bugged out. As he performed, it was Elberfeld’s turn to have his eyes bug out. He told Jackson he had the potential to be a great player and asked him to promise that in a few years he would contact Elberfeld. [3] Possible sports hyperbole about their initial meeting aside, Jackson did come back in a few years to see Elberfeld, who asked him to join the Travelers. He joined the team, at the same time enrolling at Ouachita Baptist College (now University) at Arkadelphia, Arkansas, from which he graduated in 1923 with a bachelor of science degree.

Playing a handful of games with Little Rock in 1921, Jackson did not compile an impressive record, hitting .200 with 21 errors at shortstop. Despite this poor performance, the 18-year-old showed tremendous potential. In a year he would be on the world champion New York Giants.

John McGraw had established a wide array of friends, during his long career in baseball. He obtained Mel Ott because of his friendship with a businessman in Louisiana named Harry Williams. Williams referred Ott to McGraw and Ott became a Giant. [4]

Another of McGraw’s friends was Elberfeld; they had played against each other in the early days of the American League. McGraw trusted Elberfeld’s judgment on players and in early 1922 after hearing from several people in the Memphis area about an exceptional talent, McGraw contacted Elberfeld, who confirmed that a ballplayer for a company team in the Memphis area ought to be looked at. Based on Elberfeld’s tip, McGraw signed Bill Terry to a Giants contract on May 10, 1922. [5]

Almost simultaneously, Elberfeld recommended his shortstop, and again, listening to the Travelers manager, McGraw bought Jackson’s contract from Little Rock on June 30, to take effect when the Southern Association season ended. [6]

During that season with the Travelers, Jackson’s fielding figuratively and literally almost killed his chances to make the majors. While he raised his batting average 80 points to .280, he committed a league-leading 73 errors. Of his fielding then, Jackson later recalled, “I guess I set a world record for errors. I had a pretty good arm, see, but I didn’t have much control. A lot of those were double errors – two on the same play, a boot and then a wild throw. The people in the first-base and right-field bleachers knew me. When the ball was hit to me they scattered. ‘Watch out! He’s got it again.’ ” [7]

Literally, Jackson almost failed to make the majors when, in chasing a fly ball against the Atlanta Crackers he collided with a teammate, center fielder Elmer Leifer. The collision left Leifer with a fractured skull and a severed optical nerve, which cost him sight in his left eye. Leifer, who had played a handful of games for the White Sox the previous season, spent most of the year in the hospital recovering.

Jackson was hurt badly as well. Several years later in an interview for The Sporting News he described having suffered a fractured skull, a broken nose, and numerous cuts. [8] Given that he missed just a handful of games that season – Jackson played in 147 – the likelihood is that he did not fracture his skull but suffered a severe concussion. A later account of the collision described Jackson waking up at a hospital after having numerous gashes stitched up, one of which was so wide it connected his eyebrows.[9] While the physical effects of his injury seemed to have healed, mental effects may have lingered – Bill Terry always thought it affected Jackson’s ability to hit. Despite these factors, Jackson joined the Giants in September.

Inserted into the Giants’ lineup in the seventh inning of a game against the Philadelphia Phillies on September 27, 1922, Jackson was called out on strikes in his first major-league at bat. He appeared in two more games, finishing the season with a 0-for-8 performance. The Giants had just clinched their second straight National League pennant and were about to take on the New York Yankees in the World Series.

One of the key players on the Giants was shortstop Dave Bancroft. Obtained from the Phillies after the 1920 season, Bancroft hit over .300 in 1921 and ’22 and played solid defense. Only 32 as the 1923 season began, he seemed prepared to hold down the position for several years. Once play began however, Bancroft started to experience leg pains; in late June he developed a fever and eventually collapsed with a case of influenza that took him out of the lineup for six weeks.[10] Jackson replaced Bancroft and showed McGraw he was ready to handle the position, fielding as well as Bancroft and hitting an acceptable .275 as the Giants won the pennant for the third consecutive season.

Feeling Bancroft’s future as a player was doubtful, seeking to help Christy Mathewson build up the Boston Braves (Mathewson was the team president), and wanting to see Bancroft get a chance to manage, McGraw traded Bancroft (along with Casey Stengel) to the Braves and gave the shortstop position to the 21-year-old Jackson. That Bancroft had hit just .083 in the 1923 World Series against the Yankees (Jackson flied out in his sole at-bat) undoubtedly helped McGraw make his decision to trade Bancroft. The team had won three consecutive pennants and McGraw was aiming for an unprecedented fourth with a new shortstop.

Pressure on Jackson was great as many forecasters expressed concern about his ability to replace Bancroft. These concerns were exacerbated when Jackson failed to perform well in spring training. In an awkwardly titled article, “Jackson May Not be Able to Fill Bancroft’s Shoes Acceptably” sportswriter Davis Walsh of the Pittsburgh Press advised readers that, “Jackson is neither hitting or fielding after the manner of his 1923 performance. In fact the situation has become such that there is some talk of a general shift in the Giants array.” [11]

But despite a slow start, Jackson stepped into the position and performed well. Coming into his own, he played almost every game and impressed with his wide range, quick release, and powerful arm. While Jackson still had rough edges to smooth out – he made a league-leading 58 errors in 1924 – his accuracy improved and his arm was soon considered the most powerful in the game. Jackson’s reputation for his throwing ability lasted for decades. In 1960 Al Lopez, then manager of the White Sox, was asked to compare the abilities of shortstops he had seen during his playing and managing career against those of his current shortstop, Luis Aparicio. Lopez advised that “Aparicio has the best arm of any shortstop today. He ranks with Travis Jackson and Glenn Wright in that department.” [12]

Jackson was known primarily for his defense, but was no weakling on offense, He hit .302 in 1924 and ranked high in several offensive departments, including home runs (tenth in the league with 11).His career batting average was.291. (His hitting must be viewed in the context of the era in which he played. His .302 was only 19 points above the National League average of .283 in 1924, which was a time when batting averages were well over the historical norm. While a .291 average is seen as the mark of a solid hitter in the 21st century, in Jackson’s time his hitting was overshadowed by his fielding.)

Jackson’s overall performances and his aggressiveness on the field fit McGraw’s brand of baseball. With position players like High Pockets Kelly, Heinie Groh, Irish Meusel, Hack Wilson, and Ross Youngs and pitchers like Virgil Barnes, Jack Bentley, and Art Nehf, the Giants were able to withstand runs at the pennant by the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates to win an unprecedented fourth straight pennant. Their opponent in the World Series was the Washington Senators, who were making their first appearance in the Series. Although the Senators were the sentimental favorites because of Walter Johnson’s first appearance in a World Series, the Giants were considered the better team. Before the Series began, the Giants and all of baseball were distracted by publicity surrounding a bizarre incident that occurred in the closing days of the season.

Philadelphia Phillies shortstop Heinie Sand told National League President John Heydler that Giants infielder Jimmy O’Connell had approached him before a game during the closing week of the season, before the pennant was clinched, and said, “I’ll give you $500 if you don’t bear down too hard.” Sand replied, “Nothing doing.”

Word of the incident made its way to Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Under questioning, O’Connell told Landis he had offered the bribe at the suggestion of Giants coach Cozy Dolan. Dolan in turn said that Frisch, Youngs, and Kelly knew about it, but the three adamantly denied any knowledge of the matter. O’Connell wound up being banned from baseball for life. He always felt that he had been double-crossed. “I’ve been a damned fool,” he said. “They were all in on it and they deserted me when they found I was caught.” [13] Subsequent conjecture suggests that O’Connell, a reserve infielder who had previously been the butt of several practical jokes, may have been put up to a prank that had gone horribly wrong.

More than 50 years later Jackson was asked to comment on the incident and had an interesting take on it: “I was a young player on the team, and if Frisch or Kelly or Youngs had asked me to contribute to some kind of pot or even do what O’Connell did, why, I probably would have.” [14]

The incident cast a pall over the Series and caused many to root for Washington to beat a team mired in unsavory controversy. The Senators upset the Giants in seven games, the final game won by Johnson, who made a dramatic appearance out of the bullpen in the ninth inning to shut down New York for three innings. Jackson made a crucial error in the bottom of the 12th, setting up Washington’s winning rally. A series that began badly ended badly. It would be nine years before the Giants won another pennant.

McGraw, increasingly losing touch with the game, failed to replace aging veterans with new talent as Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Chicago took pennants. During this time Jackson continued to provide solid defense and competent hitting to keep the Giants in contention. He had the opportunity to play with Frisch, Rogers Hornsby, Lindstrom, Ott, Terry, Youngs, and Carl Hubbell. Among these stars he held his own and, considered their leader, was named captain of the team.

Jackson’s play continued to improve, and eventually he gained the nickname Stonewall, or Stoney, for his ability to stop balls from going through the infield, in much the same manner as General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson held Union troops at bay during the Civil War. He became an excellent bunter. Casey Stengel called him “the greatest bunter I ever saw.” [15] Jackson became particularly adept at dragging bunts for hits. The boost to his batting average helped him hit over .300 five times after 1924, including .339 in 1930, a year in which the entire National League hit .303.

Jackson’s personal life was as successful as his career. On January 24, 1928, he married Mary Blackman, a childhood friend, also a native of Waldo. Their marriage produced two children, Dorothy, born the following October and William, born five years later. Travis and Mary made Waldo their home the rest of their lives until Travis’s death in 1987.

If marital bliss came to Jackson, good health did not. Over the years he experienced a series of ailments that seriously affected his playing time. The first major injury he suffered was in July 1925, when he tore the cartilage in his right knee in a game against St. Louis. Jackson was out of the lineup for almost a month. His loss hurt the Giants. The day Jackson went out they had a one-game lead over Pittsburgh. When he came back in mid-August, Pittsburgh had surged to a 5½-game lead and was never headed, eventually winning the pennant by 8½ games over a Giants team that barely played .500 ball the last two months of the season.

Illness also marred Jackson’s career. He had an appendectomy at the beginning of the 1927 season, a serious bout with the mumps in 1930, and influenza in 1932. All this time his knees continued to give him problems; in 1932 he was hampered by bone chips in a knee. After the season he had surgery on both knees; this allowed him to play another three seasons. To avoid the strain on his knees, Jackson shifted to third base the last two years of his career. [16] Numerous articles during this era speculated on the state of Jackson’s health, asserting that the Giants’ fortunes were tied to whether he could play.

During much of this time the Giants finished in the first division. In 1927 and 1928 they finished only two games out of first place, but more often they were also-rans. During the eight-year stretch 1925-1932 Jackson played in more than 140 games just three times; usually he missed 20 to 40 games a season. In both 1932 and 1933 he missed more than 100 games, but in the latter season he was part of a rejuvenated Giants team that captured the pennant and avenged themselves against the Senators by beating them in five games to win the World Series. Jackson played in only 53 games that season but his contributions were critical. He filled in late in the season for third baseman Johnny Vergez, who was sidelined with appendicitis. He hit only .246 but his steadiness in the field helped the Giants to maintain their hold on first.

During the Series Jackson hit poorly (4-for-18, .222) but flashed his ability in Game Four. With the score tied, 1-1, Jackson led off the 11th inning with a drag-bunt single and scored the winning run on a hit by Blondy Ryan to give the Giants a 3-games-to-1 advantage. Writing for the Universal Service during the Series, Jackson said of the game-winning rally: “I’ve punched out quite a few hits in my time, but none that have given me greater gladness than the one I punched out yesterday in the eleventh to start our rally.” [17]

Jackson started at third base in Game Five the following day as Giants pitcher Dolf Luque fanned the Senators’ Joe Kuhel with the tying run at second base in the bottom of the tenth inning to clinch the championship. Jackson concluded his write-up on the Series the next day rather laconically, saying he thought the Series was going to go six games and that the Giants could not have won without manager Bill Terry at the helm. [18]

Winning the championship was a career thrill, but the Jackson family gained some personal joy a little over a month later when on November 15 Mary Jackson gave birth to William Travis Jackson. Said the proud father, “He’ll be a ballplayer.” [19]

Recovered from his knee surgery. Jackson spent most of the 1934 season back at shortstop. Despite being considered a has-been at the age of 30, Jackson played three more years. He later spoke about being written off prematurely: “It’s a great sensation to read your own obituary – and you baseball writers certainly wrote enough of them about me – and then figuratively to kick off the top of your casket, and go out to the wars once more.” [20]

About this time Jackson received hitting advice from Terry, who felt Jackson had become too much of a pull hitter. Terry felt that Jackson shied away from the plate as a reflex action because of his collision with Elmer Leifer in 1922. It seems an odd observation; a tendency to pull away from the plate would have been exploited by pitchers early in Jackson’s career.[21] Nevertheless, Terry’s advice helped; Jackson’s batting average rose a bit, to .268, in 1934, and he drove in 101 runs, the only time in his career he exceeded 100 RBIs. His hitting rebounded even more in 1935, to .301.

In 1934 Jackson was chosen as the National League’s starting shortstop in the second annual All-Star Game. He was hitless in two at-bats before giving way to future Hall of Famer Arky Vaughan. While surely gratified at recognition of his skills, Jackson was disappointed by the Giants’ loss of the pennant during the last few days of the season to St. Louis when Brooklyn spoiled the Giants’ chances as payback for Bill Terry’s “Is Brooklyn still in the league?” comment the preceding winter.

In 1935 Jackson played exclusively at third base as the Giants came in third. Although he hit over .300 for the final time in his career, his knees were starting to give him trouble again. The next season, 1936, would be his last, and he got to play in his fourth World Series.

Led by Carl Hubbell’s 26-6 record and Mel Ott’s league-leading 33 home runs, the Giants won the pennant by five games over Chicago. Ten games out in the middle of the season, they surged back, winning 24 out of 27 games in one stretch in August, and clinched the pennant on September 24. Jackson scored the decisive run in the tenth inning on a base hit by pitcher Hal Schumacher. It turned out to be Jackson’s final regular-season game.

The Giants’ opponents in the World Series were the heavily favored Yankees. While Hubbell won the opening game, the Series ended for the Giants after six games. Game Six, which the Yankees won 13-5, was the last major-league game played by Jackson, as well as by Bill Terry. Jackson had hit .230 for the season and noticeably slowed down in the field (New York Times sportswriter John Drebinger was describing him as “the venerable Travis Jackson”), strong indications that the time had come to step aside. He did so in January 1936, signing a three-year contract to manage the Giants’ Jersey City team in the International League.[22]

For his career, Jackson hit .291 with 1,768 hits, 929 runs batted in, and a reputation for fielding excellence second to none. He was a member of four pennant winners and one world championship squad.

Jackson originally agreed to serve as a playing manager at Jersey City. It quickly became apparent that his knees were in no shape for further play. After a handful of games in 1937 and 1938 he dropped the “player” part of his job. From the bench he managed a team composed mostly of veterans whose careers were winding down, their age inspiring local sportswriters to dub them “The Nine Old Men.”[23] They finished a dismal last.

Jackson managed through the middle of 1938, when he left the club. Accounts of why he left are murky; he either was fired and replaced by Giants scout Hank DeBerry or resigned and DeBerry took over. In either case the team was playing poorly and had shown little sign of improving over its 1937 performance. Jackson quickly joined Bill Terry as a coach with the Giants. It was later suggested that Jackson never really put his heart into the Jersey City job and wanted out.[24]

Shortly after the season ended Jackson’s father died. Travis’s first memories of baseball had been gained through playing ball with his father, who had seen his son become a successful big leaguer. Three weeks after his father died, his mother, Etta, succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage.

Jackson stayed with the Giants as a coach through 1940. He retired after contracting tuberculosis and entered a sanitarium in 1941 to regain his health, a process that took several years. After recovering, he rejoined the Giants as a coach, now under manager Mel Ott. After Ott was replaced by Leo Durocher in 1948, Jackson was let go at the end of the season, and his 27-year association with the Giants was severed.

He joined the Braves organization and managed in their minor-league system until he retired in 1961, explaining, “I got tired of the bumpy bus trips and longed for the rocking chair on the front porch.” There, he watched as a succession of former teammates were elected to the Hall of Fame. Hornsby, Frisch, Hubbell, Ott, and Terry had been selected before he retired. Youngs was picked in 1972, Kelly in 1973, Lindstrom in 1976, and Hack Wilson in 1979. The Giants infield of the 1920s was represented at every position – except shortstop.

In 1973 Bill Terry was selected to serve on the Hall’s Veterans Committee. The committee was responsible for giving a “second look” at players from an earlier era who had been passed over. Jackson received a smattering of votes over the years, but never serious consideration as selections were often based on offensive production. Terry, with a different perspective, felt defensive contributions to the game were not duly recognized.

By 1982 Terry was no longer on the Veterans Committee, but his words lingered with fellow committee members. Early in March of that year Jackson received a call informing him that he had been elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee.

Jackson was surprised and overjoyed by the news. “For a long time I thought, well I’ll be next … and then I kinda forgot all about the Hall of Fame. The longer you’re out the more time they have to forget, and I’ve been out a long time. I was really surprised and happy. Anybody who ever played ball wants to go to the Hall of Fame. Don’t let any of them kid you.”[25]

His selection proved a breakthrough. Edward Stack, president of the Hall of Fame, said that the meeting at which Jackson had been selected “included considerable discussion about middle infielders.” Stack said he hoped with Jackson’s selection that more middle infielders such as Pee Wee Reese and Phil Rizzuto would be considered. Jackson’s election did pave the way in breaking precedent. Reese and Rizzuto were later admitted, as well as players like Ozzie Smith and Roberto Alomar who while capable with the bat, influenced the game more through their defensive skills.

Despite health issues, there was no question that Jackson would go to Cooperstown for his induction. His he was accompanied by his wife, Mary, children Dorothy and William, three grandsons, and two granddaughters. Bill Terry also came. Although coming late in life, Jackson appreciated the honor given to him.

On July 27, 1987, five years after being inducted, Jackson died at home from Alzheimer’s disease. He was 83 years old.

Asked once about his greatest thrill in the game Jackson spoke not of World Series, Hall of Fame teammates, meeting presidents or individual accomplishments. He thought of the time more than 60 years before when he stood on a professional baseball field for the first time. “…[T]he first time I stepped on the field I was in awe. It held 4,500 people or so and I never saw a park that big. And there I was holding my pants up with a cotton rope.”

April 24, 2011

[1] This was obtained from an extensive series of newspaper clippings, mostly undated, contained in a file on Jackson provided by Bill Francis at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

[2] “Travis Jackson Began Tossing a Ball at Age of Three, Playing with Dad – and Kept on Until he Became Star,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1930.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Alfred M. Martin, Mel Ott: The Gentle Giant, (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003). 14-21

[5] Peter Williams. When the Giants Were Giants; Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball. (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books, 1994), 10-15, 310.

[6] Noel Hynd. The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants. (New York: Doubleday, 1988). 232.

[7] “Travis Jackson, a Shortstop Who Made the Hall of Fame,” New York Times obituary, July 29, 1987.

[8] The Sporting News, June 11, 1930.

[9] Hynd, 143.

[10] Trey Strecker, Dave Bancroft, SABR Biography at http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=951&pid=560

[11] Pittsburgh Press, March 19, 1924, 27.

[12] Furlong, Bill. “Luis Aparicio: Artist at Work,” In Ray Robinson, ed. Baseball Stars of 1962. (New York: Pyramid Books, 1962). 155.

[13] Charles C. Alexander. John McGraw. (New York: Viking Penguin, Inc., 1988). 257.

Full Name

Travis Calvin Jackson

Born

November 2, 1903 at Waldo, AR (USA)

Died

July 27, 1987 at Waldo, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.