Welcome Gaston

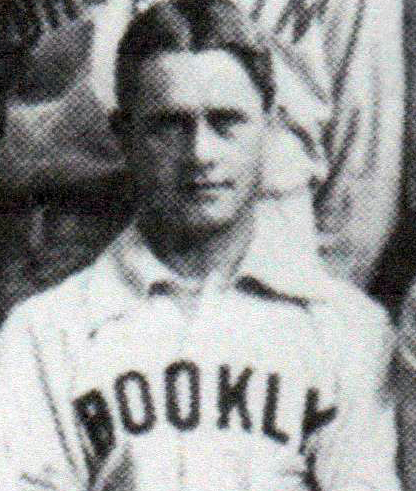

A turn-of-the-20th-century left-hander with a singular first name, Welcome Gaston’s brief major league career included events out of the ordinary, as well. During his October 1898 audition with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, for example, Gaston started four National League games – but only two made the record books; his other two outings were called off before the completion of the five innings required to qualify as an official game. Including a relief stint for Brooklyn the following April (which, perhaps predictably, was also abbreviated by unplayable conditions), Gaston walked 13 of the 89 enemy batsmen he faced but struck out none. By so doing, he set an oddball major league pitching record that stands to this day: most career walks without a strikeout.1

A turn-of-the-20th-century left-hander with a singular first name, Welcome Gaston’s brief major league career included events out of the ordinary, as well. During his October 1898 audition with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, for example, Gaston started four National League games – but only two made the record books; his other two outings were called off before the completion of the five innings required to qualify as an official game. Including a relief stint for Brooklyn the following April (which, perhaps predictably, was also abbreviated by unplayable conditions), Gaston walked 13 of the 89 enemy batsmen he faced but struck out none. By so doing, he set an oddball major league pitching record that stands to this day: most career walks without a strikeout.1

Upon being returned to the minors, Gaston played through the 1903 season before entering the business world of smalltown Ohio. But he remained active in the game at the local level, and in 1914 began a minor league umpiring career that lasted into his sixties. Gaston was still promoting baseball when he succumbed in a Columbus hospital to a post-surgical heart attack in December 1944. His story follows.

Welcome Thornburg Gaston was born on December 19, 1874, in Senecaville, Ohio, a rural hamlet located about 90 miles east of Columbus. He was the younger of two children born to stone mason Milton Baldrige Gaston (1850-1934) and his first wife, Margaret (née Patterson, 1851-c.1875). Following the death of his spouse, Milton’s second marriage to Edna Purdom eventually provided our subject and older sister Lola with nine half-siblings.2 Welcome3 was educated in local schools before matriculating to nearby Scio College. He appears not to have obtained a degree4 but nevertheless acquired an education sufficient to land a job teaching school in Cumberland, a village adjacent to his birthplace.5

Press mention of Gaston’s baseball playing career dates to the summer of 1895, when he pitched for an amateur nine from Caldwell, Ohio. “Gaston, the splendid pitcher from Senecaville, was placed in the box by Caldwell to fool our boys with his puzzling curves,” reported the Zanesville Daily Signal in recounting the hometown Buckshoes’ 4-3 victory in early August.6 Looking back, the passage is telling – suggesting that Gaston was not a fastball pitcher even in his youthful amateur days. Rather, he was “a junkballer who relied on strong [defensive] support” to keep the opposition in check.7 The following summer, Gaston donned the uniform of the Cambridge Colts, a fast local amateur club that featured future major leaguer Jimmy Delahanty.8

In time, word of Gaston’s standout pitching reached Connie Mack, then field skipper of the National League’s Pittsburgh Pirates. At season’s end, Gaston was among the prospects signed to a Pittsburgh contract for the next year.9 After a brief look in the Pirates’ 1897 spring camp, the young left-hander was released to the Toronto Maple Leafs, a high minor Eastern League club managed by former major league shortstop Arthur Irwin. During the preseason, Gaston seemed to have solidified his place on the Toronto roster with “a most creditable exhibition” in a complete-game loss to the National League’s Washington Nationals.10 Yet early in the regular season, he was dispatched to the Taunton (Massachusetts) Herrings, a lower-level New England League club in need of pitching help that was managed by former major leaguer John Irwin, Arthur’s younger brother.11 Whatever the private arrangement between the Irwin brothers, the transfer was short-lived and by late May Gaston was back in Toronto. He set down the Buffalo Bisons in his maiden Maple Leafs start, 11-6,12 and soon assumed a place in the Toronto rotation.

With a roster that included oncoming Deadball Era stalwarts Bill Dinneen, Buck Freeman, Dan McGann, Harry Staley, and 14 other future major leaguers,13 the 1897 Maple Leafs were a formidable team. And after a slow start, Toronto rallied to a second-place (75-49, .605) finish in final Eastern League standings. Rookie Welcome Gaston did his part, chipping in a solid 13-8 (.619) record, with a team-leading 1.67 ERA in 23 appearances. A decent-hitting pitcher throughout his professional career,14 he also contributed with the bat, posting a .299 (20-for-67) batting average. Gaston then split a pair of decisions against the first-place Syracuse Stars during Steinert Cup play, the postseason competition that determined the Eastern League champion. But by the time that the abandoned-in-progress match was awarded to Toronto by EL officials,15 Gaston was in residence at a Toronto hospital, suffering from typhoid fever.16 Meanwhile, Toronto reserved him for the 1898 season.17

Recovered from his illness, Gaston returned to Toronto and turned in another solid season in 1898. Pitching for a club that fell to third place (64-55, .538) in the Eastern League pennant chase, he went 16-12 (.571) in 34 mound appearances. Gaston was also occasionally stationed in left field, even though his batting average tailed off to .216 (29-for-134). During the campaign, an unidentified Toronto sportswriter offered the following impressions. “Gaston is a young cub, who seems to me always particularly sleek and clean, like one newly risen from the bath, and with his hair parted,” the scribe mused, before adding “He is a puzzle to the batsmen … The chief fault to be urged against Gaston is that he ‘rattles,’ by which … I mean his equanimity deserts him in emergencies, and that his opponents play upon his nervousness.”18 Gaston was also reportedly a slow worker on the mound.19

Such purported shortcomings did not deter Brooklyn Bridegrooms honcho Charles H. Ebbets, busily stockpiling talent for his club as the National League season wore down.20 Gaston was among the 15 minor league prospects for whom Ebbets acquired rights in early October.21 The newcomer made his major league debut in a home game against the Washington Nationals on October 4 – or so it seemed until “a heavy downpour of rain turned the Washington Park diamond into a cluster of mud puddles and prevented further play.”22 In three innings of erased work, Gaston blanked the Nats on two infield hits, while walking three. The hometown press was favorably impressed, with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle opining that “Gaston had shown himself to be perfectly at home in league company,”23 while the Brooklyn Times declared “he did well.”24

The name Welcome Gaston was permanently inscribed in the major league record book two days later when he lost a complete-game effort to the Boston Beaneaters, 7-4. Despite the outcome, the Brooklyn press remained supportive, attributing the defeat to shoddy Grooms infield defense and deplorable umpiring.25 But Gaston was responsible for the 12 base hits accumulated by Boston, if not entirely for the seven free passes that he issued – “it was agreed on all sides that [umpire Tom] Brown gave Gaston a rough deal” on balls and strikes.26

The left-hander entered the win column the following week, setting down the Philadelphia Phillies on October 11 in a contest shortened to seven innings, 14-2. Gaston held the opposition to five scattered hits and walked only two. He also helped himself with the bat, smashing a triple and scoring twice. This performance led the Brooklyn Citizen to exclaim, “‘Welcome’ made good in great shape, and there is no doubt that he will be one of the shining lights of Ebbets’ salary list next season.”27 The Daily Eagle concurred, praising “the remarkably clever work of Welcome Gaston,”28 while the Standard-Union observed that “Gaston again pitched a first-class game.”29

On the final day of the 1898 season, Gaston was on the slab again, starting the second game of a doubleheader against Philadelphia. Like his aborted debut, this effort was invalidated when the game was called on account of darkness after Brooklyn completed its at-bats in the top of the fourth. And that was probably just as well for Gaston, as he had surrendered five runs in his first three innings work and trailed 5-3 when the action was stopped.30 Reduced to the contests of official record, Gaston posted a 1-1 record in two complete-game starts, with a respectable 2.81 ERA in 16 innings pitched. Over that span, he allowed 17 base hits and nine walks, with no strikeouts. That showing was good enough for “the Brooklyn Club … to hold … Gaston for further trial next spring.”31 In the meantime, Gaston hooked on with the Hamilton (Ontario) Blackbirds of the independent Canadian League, splitting two late October verdicts.

Over the winter, the chances of Gaston or any unproven pitcher making the Brooklyn roster were dramatically reduced by an off-field event: the ownership merger of the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and Baltimore Orioles franchises. Accompanying club co-owner and former Orioles manager Ned Hanlon to Brooklyn – the Bridegrooms were soon renamed the Superbas in Hanlon’s honor32 – was the crème of Baltimore’s everyday lineup: outfielders Willie Keeler and Joe Kelley, shortstop Hughie Jennings, and first baseman Dan McGann.33 Orioles 20-game winners Doc McJames, Jay Hughes, and Al Maul also changed into Brooklyn livery for the 1899 season.

Despite the influx of talent, Gaston’s performance in spring camp – especially a four-inning exhibition game stint in which he held the Brooklyn regulars at bay – impressed both the club’s press corps and its new manager.34 “Hanlon thinks he has a rare find in Southpaw Gaston,” declared the Brooklyn Times. “The ex-Toronto lad has turned out to be a much more valuable acquisition … than the manager anticipated.”35 Against the odds, Gaston made the Opening Day roster but was among expendable Brooklyn players actively being shopped by the club as the season started.36

The campaign was nearly two weeks old when manager Hanlon summoned Gaston in the top of the sixth inning of an April 28 game against the Baltimore Orioles with the Superbas trailing, 11-8. He retired the first two Orioles batters but then surrendered two singles and a walk to load the bases. Baltimore third baseman-manager John McGraw thereupon beat out a bunt to up the Orioles’ lead by another run. Gaston blanked the Orioles over the next two frames and was then the catalyst of a Brooklyn comeback, blasting “a great drive to the right field fence” that drove in two runs and deposited the pitcher on second.37 But a Willie Keeler pop-up ended the threat and left Brooklyn trailing 12-11 going into the ninth.

Two walks and a Steve Brodie double served up by Gaston promptly restored Baltimore’s margin to three runs. But when umpire John Gaffney decided that it had grown too dark to give Brooklyn its at-bats in the bottom of the ninth, the Orioles’ two-run rally was wiped out and the final score reverted to Baltimore 12, Brooklyn 11. This, in turn, recast Gaston’s pitching line to a respectable one run allowed in three innings pitched. The outing also rang down the curtain on the major league career of Welcome Gaston, as shortly thereafter he was sold to the Detroit Tigers of the high minor Western League.38

In three National League appearances spread across two seasons, Gaston officially went 1-1 (.500), with a fine 2.84 ERA in 19 innings pitched. Over that span, he allowed 20 base hits, yielding a .267 opponents’ batting average, and issued 13 walks. But these numbers would have been considerably higher had not unplayable field conditions and/or darkness necessitated the erasure of some of Gaston’s work from the record book. His strikeouts total, however, would have remained constant at zero. On the plus side, Gaston had been productive with the willow, smacking a double and a triple and driving in three runs in his nine at-bats for Brooklyn.

After a brief holdout over salary,39 Gaston joined the Tigers and quickly settled into the rotation. The season, however, was marred by a midsummer tragedy. On the evening of July 30, Gaston, a friend named Frank Sullivan, and their dates rented a small rowboat for a moonlight excursion on the Detroit River. About 30 minutes into the cruise, the little craft took on water and then capsized, launching its four occupants into the water. Gaston, described in news accounts as “an expert swimmer,” managed to rescue one panic-stricken young woman but the other disappeared into the darkness.40 A week later, the lifeless body of Jeannie Struthers, a Detroit telephone exchange operator, was recovered from the river.41

Deemed blameless in the sad affair, Gaston soon resumed pitching for the Tigers while taking an occasional turn in the outfield as well. Detroit’s eventual third-place (64-60, .516) finish was considered a disappointment by the local press, but “the good work of [pitchers Jack] Cronin and Gaston, who have been doing double duty, cannot be overlooked,” maintained the Detroit Free Press.42 In 25 appearances in the box, Gaston went 12-10 (.545), with a meager 14 strikeouts compared to 76 walks in 189 innings pitched. At the plate, he posted a .215 (22-for-102) batting average in 30 games, overall.43 After the season, Gaston was placed on Detroit’s reserve list for 1900.44

Over the winter, the Western League adopted the name American League, a precursor to its claiming major league status in 1901. For the time being, however, the newly christened circuit remained a high minor league. The 1900 campaign, however, was not a happy one for Welcome Gaston. He was ineffective on the rubber, yielding 85 baserunners (60 hits and 25 walks) versus a mere six strikeouts in 46 innings and going 1-4 (.200) with an 8.22 ERA in eight early-season appearances. Released by Detroit, Gaston flunked a tryout with an AL rival, the Cleveland Lake Shores, being “pounded all over the lot” by his former teammates in a late June loss to the Tigers, 10-3.45

After sitting at home in Ohio for a month, Gaston was given a shot by another Buckeye minor league club, the Dayton Veterans of the Class B Inter-State League.46 Despite notching an uncharacteristic five strikeouts, he lost his Dayton debut to the Mansfield (Ohio) Haymakers, 6-3, and sometime thereafter was temporarily sidelined with a broken collarbone. Likely as a result of that injury, Gaston finished the season in the Veterans outfield. He played the position adequately, handling 18 chances without an error,47 but covered little ground, the Dayton Evening Herald calling him “the slowest man on the team.”48 And although good-sized for the era – approximately 5-feet-11 and 175 pounds49 – Gaston was a powerless batter, his .302 (16-for-53) Dayton batting average consisting almost entirely of singles.50

Over the winter, Gaston signed as a pitcher with the Colorado Springs Millionaires, a newly-formed entry in a reconstituted Class A Western League.51 His shoulder evidently fully recovered, Gaston assumed the role of staff workhorse for the Millionaires, a weak (45-73, .381) team that finished in the WL basement. No official statistics appear to exist for the 1901 Western League,52 but Gaston went 12-23 (.343) in Colorado Springs games for which the writer found a box or line score. Whatever his travails on the diamond that season, Gaston ended the year on an upbeat note, talking Gertrude Musser, “one of Colorado Springs’ pretty young ladies,” as his bride in late December.53 Their union endured the ensuing 43 years but was childless.

Colorado Springs re-signed Gaston, one “of the most popular men on the team last year,” for the 1902 season,54 and both he (14-16, .467) and the sixth-place Millionaires (63-75, .457) registered modest improvement in their records. With foul balls now counted as strikes, the soft-throwing southpaw even struck out 66 Western League batters in his 30 starts.55 He also made a handful of appearances in the Millionaires outfield and posted a mostly harmless .214 (22-for-103) batting average in 35 games, total.56

Although Gaston was once again placed on the Colorado Springs reserved list for the next season,57 the Millionaires had more promising arms under contract; he was sold to the Western League Denver Grizzlies before the 1903 season commenced.58 Gaston did little pitching for his new club, however, getting most of his playing time in the Grizzlies outfield or at first base. Released by Denver in early July, he joined a local semipro club. Before the month was out, his unassisted triple play as a first baseman for the D.S. Barnett club made sports page news across the nation.59

Gaston’s final engagement in Organized Baseball commenced unexpectedly in late July when he and his wife attended a Colorado Springs game. With the Millionaires crippled by injuries, Gaston “was induced to go to the clubhouse, don a suit and play first base.”60 The emergency recruit went 1-for-4, scored two runs, and played errorless defense in a 22-6 victory over the Kansas City Blues. Thereafter, he got into several more Colorado Springs contests before his mid-August release brought the professional playing career of Welcome Gaston to a close.

Once back home in Ohio, Gaston immersed himself in the business, civic, and social life of rural Guernsey County. For the next 40 years, the activities of Welcome and society butterfly Gertrude Gaston were regularly recounted in the Daily Jeffersonian, the area’s largest newspaper. Our subject became active in area Republican Party politics – serving as a central committeeman, county convention delegate, poll watcher, and election clerk – but never sought public office. He earned a living by operating restaurants, first in Senecaville, and later in Cambridge, the county seat. In 1913, he abandoned the dining room trade to open a roller-skating rink, before moving on to ownership of a billiard parlor-bowling alley. All the while, Gaston remained busy on the local baseball scene, organizing, promoting, and/or playing for Cambridge amateur teams.

In 1914, Gaston embarked upon a minor league umpiring career, accepting a position with the Western League. With the exception of several post-World War I seasons, he spent the next two-plus decades working games in the WL (1914-1915 and 1917), Three-I League (1916 and 1930), International League (1921-1929), New York-Pennsylvania League (1931), Mississippi Valley League (1932), and Middle Atlantic League (1933-1937).61 Thereafter, he spearheaded efforts to revitalize amateur baseball in the Cambridge area. During his final years, Gaston was a frequent speaker at civic group luncheons and served as secretary of the local military draft board once America entered World War II.

In October 1944, Gaston authored a five-part series of articles about his time with the Toronto Maple Leafs and other long-distant baseball experiences for the Daily Jeffersonian.62 Two months later, he underwent prostate surgery at Grant Hospital in Columbus. While recuperating, he suffered a heart attack and died in his hospital bed on December 13, 1944. Welcome Thornburg Gaston was 69. Following funeral services concelebrated by Methodist and Presbyterian clergy, the deceased was laid to rest in Northwood Cemetery, Cambridge. Survivors included widow Gertrude and seven half-siblings.

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Darren Gibson and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted herein include the Welcome Gaston file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; the Gaston profile in David Nemec, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012); US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 According to the Baseball-Reference bullpen entry for Gaston.

2 Born between 1879 and about 1900 were half-siblings Carl, Charles, Dora, Frank, Donald, Ruth, Sarah (Sally), Hobart, and Walter.

3 Although in later years the (Cambridge, Ohio) Daily Jeffersonian very occasionally referred to him as Bub or Bill Gaston, our subject was almost always identified by his unusual first name, Welcome. And despite his lengthy tenure in Organized Baseball as a player and umpire, the sporting press never coined a nickname for him. Except for the Dayton (Ohio) Evening Herald, which inexplicably thought his first name was George, Gaston was identified as Welcome Gaston in sporting page newsprint.

4 According to the 1940 US Census, Gaston attended college for three years but did not graduate.

5 As noted in Gaston obituaries. See e.g., “Welcome T. Gaston Is Claimed by Death Wednesday Evening,” Daily Jeffersonian, December 14, 1944: 1. See also, “Concerning Denver Ball Players: No. 11 – Welcome T. Gaston,” Denver Post, May 5, 1903: 9: “Welcome T. Gaston … [was] formerly [a] country school teacher in the backwoods.”

6 “Honors Are Even,” Zanesville (Ohio) Daily Signal, August 8, 1895: 5.

7 Welcome Gaston profile in David Nemec, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), 37.

8 For a photo of the club that was published more than 40 years later, see “Casey’s Famous Colts of 1896,” Daily Jeffersonian, September 6, 1939: 1. Delahanty stands directly behind a seated Gaston.

9 As reported in “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, October 10, 1896: 5, and a short wire service dispatch published throughout Ohio. See e.g., “Players for Pittsburgh,” Delphos (Ohio) Daily Herald, October 5, 1896: 2; Galion (Ohio) Daily Inquirer, October 5, 1896: 1, and Marion (Ohio) Star, October 5, 1896: 1.

10 “Senators Cannot Lose,” Washington (DC) Morning Times, April 14, 1897: 6. Washington won the game, 7-2.

11 As reported by sportswriter Jacob C. Morse in “Hub Happenings,” Sporting Life, May 15, 1897: 4. See also, Bangor (Maine) Daily Whig and Courier, May 7, 1897: 4: “Manager Irwin intends to strengthen the Taunton team at once. He has secured Pitcher Gaston from his brother Arthur’s team.”

12 See “A Win and a Loss,” Toronto Evening Star, May 31, 1897: 4: “Gaston, Toronto’s new left-hand pitcher, made his first appearance and kept the Buffalo team guessing.” Only one of Buffalo’s six runs was earned.

13 Only five of the 23 players who wore a Toronto uniform that season did not reach the major leagues.

14 Modern reference works list Gaston as bats unknown, and no express mention of which side Gaston hit from was discovered by the writer. But the direction of his rare extra-base hits suggests that Gaston batted lefty.

15 With Toronto leading three wins to one, a dispute regarding the site of the remaining games brought the match to a halt. Thereafter, Eastern League officials awarded the championship to Toronto and discontinued future Steinert Cup competitions. See “Toronto’s Cup,” Sporting Life, October 16, 1897: 7. See also, “Syracuse Fans Kick,” Buffalo Courier-Record, December 5, 1897: 22.

16 As reported in “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, October 16, 1897: 5. Some 47 years later, our subject’s reminiscences about these events were memorialized in Welcome T. Gaston, “An Outstanding Ball Team,” Daily Jeffersonian, October 9, 1944: 4.

17 Per “The Official List,” Sporting Life, October 2, 1897: 4.

18 “Chromatics,” Toronto Evening Star, June 25, 1898: 5.

19 According to “Game Won by Brouthers,” Toronto Evening Star, June 28, 1898: 5; “The Old Jonah Is Dead,” Toronto Evening Star, June 10, 1898: 2.

20 On paper, Ebbets, who also served as club secretary, held only a minority interest in Brooklyn franchise stock. But majority club owner Gus Abell was content to let the baseball-astute and energetic Ebbets guide club fortunes.

21 See “Raid on Minor Leagues,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 4, 1898: 13. See also, “Sports: The Needs of Base Ball,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Record, October 7, 1898: 3.

22 “Gaston a Likely Pitcher,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 5, 1898: 5. See also, “Rain Stopped Proceedings,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 5, 1898: 4; “Baseball Notes,” (Brooklyn) Standard-Union, October 5, 1898: 7; and “Postponed by Rain,” Brooklyn Times, October 4, 1898: 6.

23 “Gaston a Likely Pitcher,” above.

24 “Postponed by Rain,” above.

25 See “A Day of Bad Umpiring,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 7, 1898: 13, and “The Umpire’s Bad Judgment,” Brooklyn Times, October 7, 1898: 6, censuring the work of arbiters Tommy Connolly and Tom Brown.

26 “A Day of Bad Umpiring,” above.

27 “‘Quakers’ Walloped,” Brooklyn Citizen, October 12, 1898: 4.

28 “Locals Hit the Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 12, 1898: 4.

29 “Brooklyn Wins,” Standard-Union, October 12, 1898: 7.

30 See “Closed the Season with a Victory,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 16, 1898: 30.

31 “Big Deal Revived,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1898: 5. Fellow October rookie hurler Harry Howell was also slated for a spring training look-over.

32 Hanlon’s Superbas were a popular turn-of-the-century acrobatic troupe.

33 Primarily for business reasons – they co-owned a thriving Baltimore café – Orioles third baseman John McGraw and catcher Wilbert Robinson remained in Baltimore for the 1899 season.

34 See “Gaston Proved a Puzzle,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 30, 1899: 6; “Gaston’s Work Gilt Edged,” Brooklyn Times, March 30, 1899: 8. For the game, Gaston was loaned to the team of a Michigan army unit bivouacked near the Brooklyn training grounds in Augusta, Georgia.

35 “Hanlon Thinks Well of Youngsters,” Brooklyn Times, March 31, 1899: 8.

36 As reported in “Baseball Notes,” Brooklyn Times, April 22, 1899: 6. Others on the market included catcher Pat Crisham, catcher-infielder Joe Yeager, and pitcher Dan McFarlan.

37 Per “Pitchers Were Slaughtered,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 29, 1899: 5.

38 As reported in “Base Ball Notes,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, May 18, 1899: 14; “Brooklyn Releases Pitcher Gaston,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 18, 1899: 4; and elsewhere.

39 See “Gaston Deal Hangs Fire,” Detroit Evening News, May 21, 1899: 3; “Gaston Holding Off,” Columbus Dispatch, May 20, 1899: 9.

40 Details of the Struthers drowning were subsequently published in “Struggles Against Death,” Pigeon (Michigan) Progress, August 4, 1899: 1; “Miss Struthers,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, August 3, 1899: 5; and elsewhere.

41 Per “Gave Up Its Dead,” Detroit Evening News, August 4, 1899: 1. The deceased was the teenage daughter of Gaston’s Detroit landlady.

42 “Western League Wind-Up,” Detroit Free Press, September 10, 1899: 28.

43 Per Official 1899 Western League stats published in Sporting Life, October 21, 1899: 6, and the 1900 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 60, 65. Strikeouts, walks, and innings pitched as calculated by the writer from Western League box scores. Baseball-Reference provides no data for Gaston’s 1899 season with Detroit.

44 “Western League Reserve List,” Sporting Life, September 30, 1899: 2.

45 “Cronin’s Good Work,” Dayton Evening Herald, June 29, 1900: 6.

46 The signing of George Gaston, “the southpaw twirler from Cambridge,” was reported in the Dayton Evening Herald, August 4, 1900: 6. A subsequent announcement of Gaston’s acquisition repeated the strange misnomer. See “Dayton Doings,” Sporting Life, August 25, 1900: 11.

47 According to Inter-State League fielding stats published in Sporting Life, November 3, 1900: 10. Baseball-Reference provides no statistical data for Gaston’s time with Dayton.

48 “Base Ball Gossip,” Dayton Evening Herald, September 26, 1900: 6.

49 Present-day baseball authorities provide no height and weight for Gaston and none was uncovered by the writer during research. The guesstimate above is based on the known size of players (Ralph Miller, Fritz Buelow, Earl Moore) whom the press said Gaston closely resembled physically. Registering for the WWI draft in 1918, Gaston described himself as tall with a medium build.

50 Per Inter-State League batting stats published in Sporting Life, September 29, 1900: 11. Gaston did not satisfy the minimum requirements to have his Dayton pitching stats listed.

51 The Gaston signing was reported in “Outlook for the Millionaires,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, December 29, 1901: 9.

52 This may well have been a byproduct of Western League President Thomas J. Hickey’s hasty departure at season end to assume a similar post with the outlaw American Association. At the time, minor league stats were customarily compiled and distributed by the league president.

53 “Gaston Married,” Florence (Colorado) Daily Tribune, January 3, 1902: 2. State of Colorado marriage records establish that the Gaston-Musser wedding took place in Denver on December 28, 1901.

54 “Baseball,” Colorado Springs Gazette, January 1, 1902: 51.

55 Foul balls were not counted as strikes until the early 1900s. See Richard Hershberger, Strike Four: The Evolution of Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019), 239-243.

56 Per Western League stats published in the 1903 Reach Official Base Ball Guide, 192, 198. See also, “The Season’s Work,” Sporting Life, December 27, 1902: 9.

57 “Minor Reserves,” Sporting Life, October 25, 1902: 8.

58 Per “Western League News,” Sporting Life, March 14, 1903: 7. See also, “Sporting Notes,” Colorado Springs Gazette, March 2, 1903: 3.

59 See e.g., “Made a Triple Play,” Huntington (Indiana) Evening Herald, July 20, 1903: 1; “Lone Hand Triple Play,” Minneapolis Journal, July 20, 1903: 16; “Made Triple Play with No Assistance,” Salt Lake Telegram, July 20, 1903: 8.

60 “Crippled Millionaires Cinch First Place,” Denver Post, July 26, 1903: 24.

61 As reflected in Gaston’s TSN contract card and contemporaneous sports page reportage. See also, Mahlon L. Henderson, “Potpourri,” Daily Jeffersonian, February 26, 1932: 4.

62 See Welcome T. Gaston, “An Outstanding Ball Team,” Daily Jeffersonian, October 9-13, 1944.

Full Name

Welcome Thornburg Gaston

Born

December 19, 1874 at Senecaville, OH (USA)

Died

December 13, 1944 at Columbus, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.