Wickey McAvoy

In his first three professional seasons, James “Wickey” McAvoy played for a World Series champion, an American League champion, and a team that lost 109 games. This dramatic shift of fortune required no action on McAvoy’s part: The catcher joined Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics in 1913 and lingered there as Mack traded some of his stars, lost others to the upstart Federal League, and struggled to replace them.

McAvoy hit .199 in 235 games with the Athletics between 1913 and 1919, then played in the minor leagues through the 1920s. After his pro career ended, he went home to Rochester, New York, where he represented his generation of ballplayers at hot-stove events well into the 1970s.

James Eugene McAvoy was born in Rochester on October 20, 1894. His parents, James J. and Theresa, were Irish immigrants.1 As of 1900, James J., an iron molder, and Theresa had been married for 11 years and had had six children, of whom four were living. The family had grown to three daughters and four sons by April 1910, when James J. died at the family home at 42 years of age.2 The younger James had already left school by then; he later said that his formal education ended at eighth grade.3

McAvoy’s athletic career brought him into contact with numerous stars, and this pattern of mixing with legends might have started on the sandlots of Rochester. As an adult, McAvoy claimed to have played ball with Walter Hagen, another sporty young Rochesterian who gave up on formal education at middle-school age. Hagen, two years older than McAvoy, was reportedly skilled enough at baseball to receive a tryout offer from the Philadelphia Phillies. He opted instead for a flamboyant and legendary career in golf, where his credentials include two U.S. Open wins and the informal title “father of professional golf.”4 For his own part, McAvoy said his goal was always to become a pro baseball player.5

It’s not clear when Jimmy McAvoy acquired the nickname “Wickey,” which has come to replace his given name in baseball encyclopedias and online statistical databases. Searches of newspaper archives indicate that the nickname was only sparingly used during McAvoy’s major-league career, although it became more popular during his minor-league years in the 1920s.6

McAvoy moved from the sandlots to the pros at age 18 in 1913, and his ascent was rapid—though it began with failure. He obtained a preseason tryout with the Rochester Hustlers of the Double A International League, then one step beneath the majors. The Hustlers were a strong club—they went 92-62 in 1913—and McAvoy didn’t stick with the team.7

McAvoy caught on instead with the Berlin team of the Class C Canadian League, based in Kitchener, Ontario. He hit .303, second-best on the team, and was described as the loop’s best young prospect behind the plate.8 (His playing height and weight were listed at 5-foot-11 and 172 pounds; it’s a fair question whether McAvoy had attained his full growth when he began his pro career.)

The Syracuse team of the Class B New York State League put in an offer to buy McAvoy’s rights.9 But Mack and the Athletics came calling, and McAvoy played his first big-league game on September 29, 1913, less than a month before his 19th birthday. He was part of a lineup filled with recruits and debutants as Mack rested his regulars for the World Series.10 McAvoy went 0-for-3 with a strikeout as Washington’s Walter Johnson won his 36th game of the season, 1-0. McAvoy ended a Philadelphia rally in the fourth inning by grounding into a 6-4-3 double play with the bases loaded.11

All told, the youngster took part in four of the Athletics’ last six games—including three starts—and hit .111. He picked up his only hit of the season off Washington’s Jack Bentley on October 1.

How did the teenage rookie jump from Berlin to the big time? One of McAvoy’s hometown newspapers, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, credited a pair of local sports figures, Monsignor John Sullivan and Cornelius Buonomo, with tipping off Mack to McAvoy’s talent.12 Other sources reported a simpler and more likely-seeming connection. McAvoy’s Berlin manager, Jack White, was a Philadelphia resident who went home in early September and urged Mack to give the young catcher a tryout. Summoned to Philadelphia, McAvoy impressed Mack and won a contract.13

Mack, a fellow first-generation Irish-American14 and a former catcher, apparently took a liking to McAvoy. The two ran into each other in Philadelphia just before the World Series started, and Mack asked McAvoy, who was ineligible to play, why he hadn’t gone home to Rochester. McAvoy replied that some hometown friends had come to see the Series, and he’d decided to join them. The following day, Mack sent a check for $200 to McAvoy’s hotel to help him entertain his friends.15

The two men maintained a mutual admiration society over the course of decades. As late as 1949, a fan from Rochester told the story of meeting Mack at a spring training game. As soon as the fan mentioned his hometown, the 86-year-old manager cut in: “Jimmy McAvoy was a great catcher.”16

In 1914, McAvoy met another baseball legend of whom he later spoke highly. McAvoy spent much of the season with Baltimore of the IL, hitting .235 in 76 games. His teammates included a Baltimore-born rookie left-handed pitcher who was about three months younger than McAvoy. Babe Ruth, McAvoy later said, was “a great pitcher and a great boy. … He was just a natural. Had everything. He was always full of fun and you just couldn’t tame him down.”17 Baltimore sold Ruth to the Red Sox in July, and he began his big-league career with five games that season.

Again summoned to Philadelphia near the end of the 1914 season, McAvoy made four of his eight appearances against Boston, though he did not face Ruth in the majors.18 He hit .125 in 16 at-bats, including a triple off Harley Dillinger of Cleveland on September 1.19

After the Athletics’ upset loss to the Boston Braves in the World Series, Mack sold some of his stars, while others jumped to the Federal League.20 The team’s record toppled from 99-53 in 1914 to 43-109 in 1915, and the Athletics did not become competitive again until 1925.21

Fans were disappointed—attendance at Athletics games dropped 57 percent year over year—but the gutting of the team gave McAvoy the opportunity to play. The 20-year-old backstop appeared in 68 games, including 42 starts. His bat was not up to the task, as he posted a slash line of .190/.236/.250 with no home runs and 6 RBIs.

The first game of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns on September 11 highlighted his ups and downs. McAvoy collected two doubles and two walks in four trips to the plate, but also threw away the ball on a stolen-base attempt that led to the Browns’ final run in an 8-4 St. Louis win. McAvoy committed 25 errors that season, second-most among AL catchers.22

Bounced back down to Baltimore, McAvoy spent the entire 1916 season and most of 1917 there. He hit just .231 in 1916 but caught fire the following season, hitting .313. This earned him a return to Philadelphia near the end of 1917, as the Athletics struggled to a 55-98 record.23

McAvoy hit .250 in 10 games with the Athletics in September and October 1917. He went 3-for-4 in a loss to Cleveland on September 22 and hit his only major-league homer on September 28. The ninth-inning solo shot into the left-field bleachers at Shibe Park denied Detroit’s Hooks Dauss a shutout in a 6-1 Tigers win.24 The Chicago Cubs reportedly showed interest in McAvoy in the offseason, but no deal was forthcoming.25 Before the 1918 season, he warmed up in chilly Rochester by playing in a series of indoor baseball games at a city armory in March to benefit a local military unit.26

With the U.S. committed to World War I, major leaguers faced an order to either enter military service or find work in military-related industry. McAvoy sought an exemption, listing himself as the sole means of support not only for his widowed mother, but for several of his younger siblings as well.27 He eventually agreed to take work in a munitions plant starting September 1, 1918, along with fellow Rochesterian George Mogridge, who also held a dependent-related exemption.28 It’s not clear if or when McAvoy reported, as he played for the Athletics as late as September 2; in any event, an armistice ended the war on November 11. (McAvoy also crossed paths with the military that season when he played first base for the A’s in an exhibition at Camp Meade, Maryland, on May 5.29)

In 1918, McAvoy set career highs in many categories, including games (83), at-bats (271), hits (66), and RBIs (32). It was the only season in which he played enough games to qualify as the Athletics’ starting catcher.30 He hit .244, including his only career four-hit game against Detroit on July 8.

McAvoy improved on the defensive side of the ledger, as well. He led AL catchers in errors (15) and stolen bases allowed (94), but also placed second in range factor and double plays turned as a catcher, as well as third in assists and runners caught stealing. Five times that season he cut down three would-be base thieves in a game. It may have made a particular difference on August 22, when his arm ended three innings on caught-stealing plays and the Athletics beat the Chicago White Sox, 3-2.31

McAvoy also made a burlesque pitching appearance in the second game of a doubleheader against Washington on September 2, the Athletics’ last game of that war-shortened season. With two outs in the bottom of the eighth and the home Senators leading, starting pitcher Mule Watson took over at first base and first baseman McAvoy came in to pitch. Washington coach Nick Altrock, just shy of 42 years old, had pitched an inning to entertain fans; he now came to the plate. McAvoy fed him a soft pitch and Altrock flared a ball into right field.32 He was allowed to circle the bases for a farcical “home run,” missing second and third bases along the way.33 McAvoy then retired Washington’s Burt Shotton on an unrecorded play. He was the last person to take the mound for the Athletics that season, in his only big-league pitching appearance.34

The Philadelphia Inquirer touted McAvoy’s potential before the 1919 season, saying he was “a strong and accurate thrower, a good receiver, and shows every indication of developing into a first-class catcher.”35 Instead, McAvoy’s bat gave way again in 1919, and he was displaced by Cy Perkins as Mack’s starting catcher. His average fell below .200 for good on May 25 and he closed the season hitting a scant .141 in 62 games.

He played his final major-league game on September 16, catching the final two innings of a 12-8 loss to Cleveland as a defensive replacement. His team slumped to a record of 36-104. During McAvoy’s final four seasons with the Athletics, they posted a record (excluding ties) of 186-387, for a winning percentage of about 33 percent.

Sent back to Baltimore, McAvoy was sold to Seattle of the Pacific Coast League in March 1920.36 Rather than go, he jumped to the Lebanon, Pennsylvania, team of industrial giant Bethlehem Steel’s company league, and from there to a semipro team in Oil City, Pennsylvania.37 The catcher was suspended from professional baseball for failing to report until he earned reinstatement in December 1921 by paying a $200 fine.38 Just 27 years old in the fall of 1921, McAvoy played minor-league ball through the 1929 season but never returned to the majors; perhaps his status as a team-jumper and a breaker of baseball’s reserve clause tarred him.

McAvoy’s remaining career took him to a variety of Northeastern ports of call, including Baltimore, Rochester, Buffalo, Williamsport, Reading, and Elmira. His first season back from his suspension might have been his best: McAvoy hit .310 with 10 homers for a Baltimore team that won the 1922 IL regular-season championship and beat the St. Paul Saints of the American Association in the Junior World Series postseason playoff.39 McAvoy hit a three-run homer in the series’ first game, and his ninth-inning grand slam won the fourth game, 7-3.40

Orioles owner-manager Jack Dunn considered selling McAvoy to a major-league team after the season—several were said to have an interest—but changed his mind after up-and-coming Baltimore catcher Joe Barry died unexpectedly of appendicitis in November 1922.41 In the 1922-23 offseason, McAvoy went abroad to play with Almendares of the Cuban League. His teammates included five members of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame, one of them former major leaguer Armando Marsans. McAvoy’s contribution to the team was modest, as he appeared in 20 of its 47 games and hit just .149.42

McAvoy’s minor-league years brought a significant change to his personal life. During his exile from pro ball in 1921, he played on mattress-maker Simmons’ company team in Kenosha, Wisconsin, while holding down a job there. Romance blossomed with a fellow Simmons employee named Bessie Peterson, and the two were married in Baltimore in April 1923.43

The couple remained together until Bessie’s death in November 1940. Their union produced a daughter, Elaine, and a son, William.44 Unfortunately, it also produced another disruption to McAvoy’s career. He tried to jump the Baltimore team in 1923 and return to Simmons and Kenosha, reportedly because his wife wanted to go home. The tempest was resolved when Baltimore sold McAvoy to his hometown team in Rochester.45

McAvoy’s career finally wound down with short professional stints in 1928 and 1929, when he played 15 games with Reading of the IL and 20 with Class B Elmira, respectively. His final pro opportunity came courtesy of Jake Pitler, formerly a Pittsburgh Pirates infielder and later a Brooklyn Dodgers coach and scout, who was managing in Elmira and signed McAvoy to bolster an injury-depleted roster.46

After his pro career ended, McAvoy remained active on the sandlot and semipro scene, sometimes in combination with his brother, George. George managed the company team of a Rochester-area retailer, Hart’s Stores, and Wickey appeared with them, including a game against the barnstorming House of David team in 1932.47 That same year, McAvoy played for a team of former Baltimore Orioles who took on the IL champion Newark Bears in an exhibition.48 And in 1939—the year the National Baseball Hall of Fame opened in Cooperstown, New York—the 44-year-old McAvoy traveled to Cooperstown for a game pitting retired stars from New York state against counterparts from Connecticut.49

McAvoy appears to have been modestly employed in his post-baseball years, with several sources from the 1930s and 1940s reporting that he worked in a bowling alley.50 This occupation landed him in hot water in 1932, when he was arrested and charged with running an illegal betting ring from the bowling alley. McAvoy pleaded not guilty, and the district attorney said he believed the ex-ballplayer was simply a front for the real operator of the gambling ring. Available sources do not specify the outcome of the case.51

In the 1950s, McAvoy supplemented his income during the December holidays with temporary jobs at the city post office.52 He also ran into tax trouble, as the federal Internal Revenue Service sought to collect more than $17,000 in allegedly unpaid taxes from him in 1953. The IRS accused McAvoy of underreporting his income in some years and filing no returns at all in others. The case was settled with a payment of $4,500 that November.53

McAvoy often attended Rochester Red Wings games, and at least once near the end of his life, he went to see the Newark (New York) Co-Pilots of the short-season Class A New York-Penn League.54 He attended the Red Wings’ season kickoff dinner in 1967, sitting at the head table with, among others, Red Wings manager and future Hall of Famer Earl Weaver.55 While he continued to love the sport, McAvoy considered players of the 1960s and ’70s “pampered” and was reportedly bitter over their high salaries.56

The old catcher apparently enjoyed the old-timer and hot-stove circuit, as news clips from the 1930s to the 1970s report his presence at many gatherings of retired athletes.57 Former big-leaguers from upstate New York who joined him at these events included Mogridge, Al Mattern, Ray Gordinier, Ken O’Dea, Howie Krist, and Bob Keegan.58

As his generation aged, McAvoy often found himself honoring fallen friends. In 1954 he attended the funeral of former teammate and Hall of Famer Rabbit Maranville in Springfield, Massachusetts.59 Death came to Connie Mack two years later, and McAvoy eulogized his former manager: “He was one of the best managers in the history of baseball, and one of the nicest to play for. … Everyone who knew him will regret his death.”60 Mack and McAvoy had crossed paths at a World Series game in New York in October 1954, and the “Tall Tactician” stunned McAvoy by remembering his former player’s name and hometown and chatting for several minutes.61 On a more personal level, McAvoy’s mother, Theresa, died in the early 1950s and his brother, George, in 1968.62

McAvoy was hospitalized with a heart problem in the spring of 1972 but recovered well enough to return to the old-timers’ circuit.63 He especially enjoyed what was reported to be his first meeting in years with former Athletics batterymate Bob Shawkey at a February 1973 gathering in Syracuse.64 McAvoy’s health subsequently declined, though, and he died in Rochester that July at age 79.

The date of McAvoy’s passing has been a matter of some confusion. The hometown Rochester Democrat and Chronicle initially reported it as July 5.65 Perhaps based on this, the July 5 date is listed on his Sporting News contract card and has also appeared in hard-copy baseball encyclopedias.66 The newspaper corrected the date to July 6 in a subsequent death notice, and as of 2024, Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet listed July 6, 1973, as McAvoy’s date of death.67 McAvoy’s brief obituary in The Sporting News sidestepped the issue, reporting that the old catcher “died recently in Rochester, N.Y.”68

Following services at St. Thomas the Apostle Church, the son of the Rochester sandlots was laid to rest at the city’s Holy Sepulchre Cemetery. He was survived by his daughter and son, eight grandchildren, four great-grandchildren, two sisters, and a brother.69

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Abigail Miskowiec and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources and photo credit

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. The author thanks the Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for research assistance.

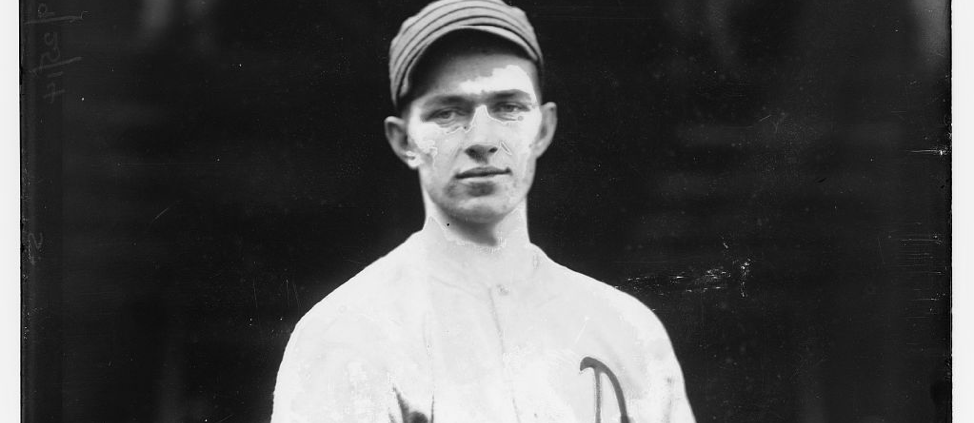

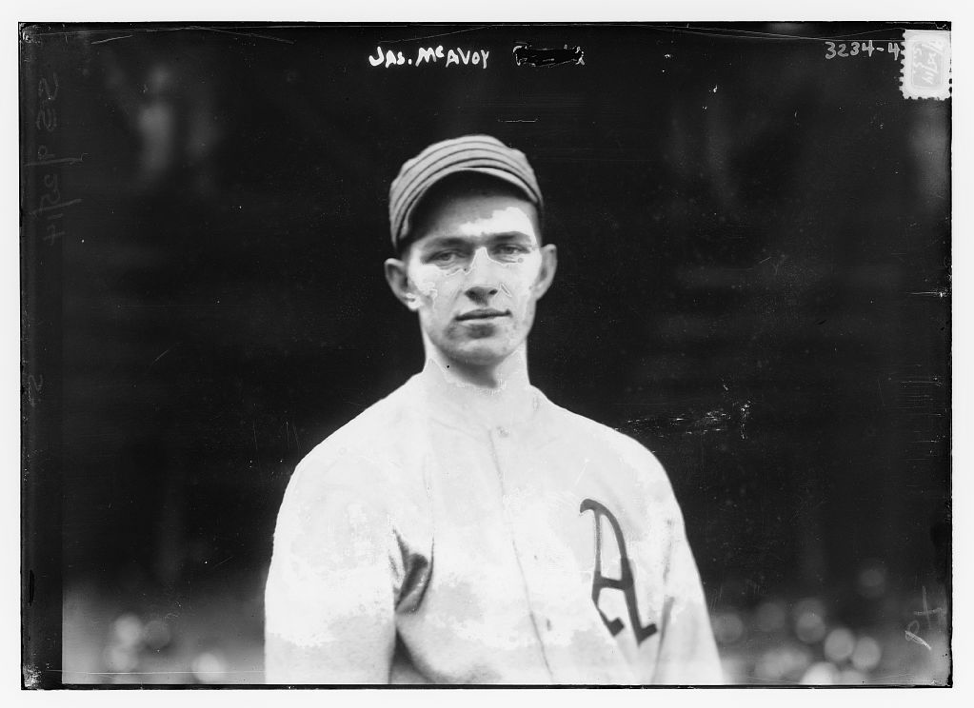

Photo of James “Wickey” McAvoy circa 1915 from the George Grantham Bain Collection of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Notes

1 As of June 2024, FamilySearch.org had New York State wedding records for four of Theresa’s children; in those records, her maiden name is spelled Hefferan, Heffron, Hefferman, and Heffernan. To make matters still more confusing, the FamilySearch page devoted to Theresa spells her name yet a fifth way: Heffernam. (Other available sources, such as US Census listings and Theresa’s newspaper obituary, do not mention her maiden name.) FamilySearch.org page for Theresa Bridget Heffernam, accessed June 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/sources/LVY7-TL9.

2 1900 US Census listing for the McAvoy family, accessed via FamilySearch.org in June 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MSJ4-XK2; “McAvoy” (death notice), Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, April 24, 1910: 21.

3 1940 US Census listing for James McAvoy and family, accessed via FamilySearch.org in June 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KQTT-LDR. In a newspaper obituary for McAvoy, a friend said that McAvoy “never finished grade school,” which is variously understood to mean either sixth or eighth grade. “Wickey McAvoy Dies at 79,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 7, 1973: 3D.

4 “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, June 27, 1922: page number not visible on online reproduction; Scott Pitoniak, “The First Giant of American Golf,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 17, 1995: Ryder Cup section: 17. The former story says Hagen and McAvoy played on the same high school team, which would have been impossible; this may have been a misunderstanding on the writer’s part. The Democrat and Chronicle ran amateur and semi-pro baseball information in the 1910s, and at least one article features players named Hagen and McAvoy on the same team, although no first names are mentioned: “Rochester’s Semi-Pro and Amateur Teams Await Bell,” April 7, 1912: 33.

5 “Wickey McAvoy Dies at 79.” Former Rochester sports journalist Ed Kreckman is quoted in this obituary; he seems the likely source of this tidbit, although it is not specifically attributed to him.

6 A search of Newspapers.com in June 2024 for “Wickey McAvoy,” across all publications, turned up 307 matches – but only four before 1920, when McAvoy left the majors. (The Newspapers.com database at that time included McAvoy’s hometown Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, as well as the Philadelphia Inquirer.) A separate search of the FultonHistory.com database, which includes many papers from New York state, returned a similar pattern of use for the nickname. The earliest use of McAvoy’s nickname in either archive was in April 1917 in a newspaper in Portland, Maine.

7 It appears that McAvoy was kept for the first few weeks of the season, but then dropped at a point when teams had to pare down their rosters. As of June 2024, Baseball-Reference had no statistical listing for McAvoy with Rochester in 1913. “Hustlers Say Farewell to Spring Training To-morrow,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 13, 1913: 35; “Walt Johnson Records his 36th Victory,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, September 30, 1913: 19.

8 “Promising Canadian Leaguers to Try for Faster Company,” Berlin News Record (Kitchener, Ontario), September 25, 1913: 8.

9 “Offer for McAvoy,” Ottawa Citizen, September 6, 1913: 9.

10 William Peet, “Connie Mack’s Recruits Bow to Walter Johnson,” Washington (District of Columbia) Herald, September 30, 1913: 10. Athletics players making their big-league debuts in this game, in addition to McAvoy, were third baseman Harry Fritz, second baseman Press Cruthers, and shortstop Monte Pfeffer. For Pfeffer, it was his only major-league appearance.

11 Stanley T. Milliken, “One Run Enough,” Washington Post, September 30, 1913: 8.

12 “Cornelius Buonomo Stricken; Blow to Rochester Sportdom,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 27, 1932: 13; George Beahon, “The Best Customer,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 1, 1962: 32.

13 “Berlin Catcher Looks Good to Connie Mack of Athletics,” Berlin News Record, October 4, 1913: 1.

14 Mack’s birth name was Cornelius McGillicuddy, and his parents, Michael and Mary, were Irish immigrants. Doug Skipper, “Connie Mack,” SABR Biography Project, accessed June 2024, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/connie-mack/.

15 “Connie Mack and McAvoy,” Brantford (Ontario) Expositor, November 11, 1913: 9. According to an online inflation calculator hosted by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, $200 in October 1913 had the same purchasing power as $6,281 in May 2024. https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl?cost1=200&year1=191310&year2=202405. McAvoy’s hometown newspaper reported that he warmed up pitchers during the Series. “Jimmy M’Avoy Receives Nice Letter from Connie Mack,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 19, 1914: 19.

16 Elliot Cushing, “Sports Eye View,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, April 11, 1949: 26.

17 Howard Kemp, “Wickey McAvoy Recalls Diamond Days with Ruth,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 17, 1948: 20.

18 On September 5, McAvoy appeared in a game against Boston’s Ernie Shore, who had also played with Baltimore earlier in the season before being sold to the Red Sox with Ruth and Ben Egan in July. McAvoy was a late-inning defensive replacement.

19 “Jim Nasium,” “Terrible Tale of Naps’ Defeat,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 2, 1914: 10. Jim Nasium was the pen name of sportswriter Edgar Wolfe.

20 Doug Skipper, “Connie Mack,” SABR Biography Project, accessed June 2024. The stars who either jumped to the Federal League or were sold by Mack included Eddie Plank, Charles Bender, Eddie Collins, Home Run Baker, and Jack Barry.

21 The Athletics also tied six games in 1914 and two in 1915.

22 Sam Agnew of the Browns led with 39—though he played 102 games behind the plate, considerably more than McAvoy’s 42.

23 With one tie.

24 Jim Nasium, “Tigers Put Check on Rookies’ Rush,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 29, 1917: 14. The Detroit Free Press’s game story referred to the catcher as “Sam McAvoy.” “Tigers Take Macks into Camp Easily,” September 29, 1917: 9.

25 “Buffalo Will Be In the League,” Buffalo Courier Express, October 11, 1917: 15.

26 “Base Hospital Men Sell Tickets from Auto Truck as Band Plays,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 1, 1918: 23; “Army Discipline for Hospitalers in Next Battle,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 6, 1918: 19; “Base Hospital Men Not There with Ol’ Bean,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, March 10, 1918: 35.

27 World War I draft card for James McAvoy, accessed via FamilySearch.org in June 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:KXBH-BZG.

28 “Big League Battery for Symington 75s,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 22, 1918: 17.

29 “Athletics Land on Former Pitcher,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 6, 1918: 12. McAvoy made one major-league regular-season appearance at first base, as well as one in right field.

30 The only other seasons in which McAvoy played more than 10 games were 1915 and 1919; the Athletics’ starting catchers in those seasons were Jack Lapp (1915) and Cy Perkins (1919).

31 This was the only one of the 1918 games in which McAvoy caught three runners trying to steal that the Athletics won. McAvoy himself ended the bottom of the sixth by getting caught trying to swipe second base. McAvoy’s personal best was four runners caught stealing in a game, which he achieved three times.

32 “Athletics Share with Senators,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 3, 1918: 10.

33 J.V. Fitz Gerald, “Griff’s Men Break Even to Finish Third in League Race as Baseball Suspends,” Washington Post, September 3, 1918: 8; Louis A. Dougher, “Griffmen Are Preparing to Scatter Homeward; Baseball Ends in Capital ‘til Hun is Licked,” Washington Times, September 3, 1918: 14.

34 It might have made sense for McAvoy and Watson to switch places again before Shotton came to the plate, and perhaps they did. But news stories make no specific mention of it, and the modern box score with individual pitching lines for each pitcher was not in vogue then, so the assumption is that McAvoy stayed in to face Shotton, who might not have given the at-bat his full effort.

35 “Will Try It with Athletics Again This Year” (photo and caption), Philadelphia Inquirer, February 13, 1919: 14.

36 “Baseball,” (Portland) Oregon Daily Journal, March 10, 1920: 14.

37 “Signing of Gallia Gives Hope to Franklin Clan,” Pittsburgh Post, August 8, 1920: 3:3; “Jack Dunn Regards Baker Reserve Contract Jumper,” Baltimore Sun, March 29, 1921: 14.

38 Don Riley, “Jack Dunn Predicts Birds’ Fourth Flag,” Baltimore Sun, December 9, 1921: 12; “Wickey McAvoy Accepts Dunn’s Terms,” Baltimore Sun, December 22, 1921: 10.

39 “Ed Rommel Hurls in Exhibition Contest,” Baltimore Evening Sun, October 21, 1922: 10.

40 Don Riley, “Catcher’s Hit Wins for Birds,” Baltimore Sun, October 10, 1922: 10.

41 “Jerry Belanger Does Not Belong to Rochester, So Owner of Hartford Says,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 8, 1922: 41; “Joe Barry, Oriole, Dies in the North,” Baltimore Sun, November 26, 1922: 23.

42 1922-23 Almendares team page on Seamheads.com, accessed September 2024, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1922.5&teamID=ALM&LGOrd=1.

43 “Jimmie McAvoy Joins Bedmakers,” Kenosha (Wisconsin) Evening News, July 20, 1921: 9; “Kenosha Girl Weds in East,” Kenosha Evening News, April 12, 1923: 4.

44 “McAvoy” (death notice), Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 24, 1940: 8C.

45 “Orioles Send McAvoy to Home Town Club,” Washington Times, June 7, 1923: Sports:1; “Dunn Puts It Over on Jumper M’Avoy,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1923: 5.

46 “Pitler Signs Good Catcher,” Elmira Star-Gazette, June 26, 1929: 18.

47 “Hart’s Stores and Marriott Teams to Battle at Newark,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 30, 1930: 20; “Hart’s Set for Battle with Beards,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 14, 1932: 17.

48 “Grove and Thomas to Hurl in Oriole-Bear Night Game,” Baltimore Evening Sun, September 24, 1932: 9.

49 Elliot Cushing, “Random Sports Gossip from All Fronts,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 15, 1939: 16.

50 These sources include the 1940 US Census, cited above, and McAvoy’s World War II draft card, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QKV7-HHV7, both accessed via FamilySearch.org in June 2024. The Census listing specifies that McAvoy was an attendant at the bowling alley, which suggests that he wasn’t the owner. Incidentally, McAvoy’s draft card lists his height and weight as 6-feet-6 and 207 pounds, measurements that are not corroborated by other sources.

51 “35 Arrested in Horse Room Raid Opening New Campaign,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 18, 1932: II:1; “Man Nabbed in Police Raid Pleads Not Guilty,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 19, 1932: 12; “Sees McAvoy Just ‘Front’ for Real Raceroom Owner, but Fowler Pushes Charge,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 24, 1932: II:1. The author of this biography searched newspaper databases on Newspapers.com, FultonHistory.com, and NYSHistoricNewspapers.com in June 2024, but found no reported outcome of the case.

52 Henry W. Clune, “Seen and Heard,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, December 27, 1952: 9.

53 “$15,915 Tax Action Names City Couple on Buffalo Docket,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 21, 1953: 21; “City Man Contests $91,918-Tax Claim,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 10, 1953: 13.

54 “Wickey McAvoy Dies at 79”; Charles Hayes, “Co-Pilots Discover Joys of Winning,” Geneva (New York) Times, July 9, 1971: 16. The Co-Pilots were a Milwaukee Brewers farm team in 1971.

55 “Red Wing Kickoff Dinner Held Here,” Vicinity Post and Tenth Ward Courier (Rochester, New York), May 10, 1967: 7, https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=twcvp19670510-01.1.7&srpos=6&e=–1913—1973–en-20–1–txt-txIN-%22james+mcavoy%22———.

56 “Wickey McAvoy Dies at 79.”

57 Conjecture: Decades later, in the 1990s, Hall of Famers Duke Snider and Willie McCovey pleaded guilty to federal tax charges for failing to report years of income from personal appearances. The author of this biography could not determine whether McAvoy was getting paid to appear at old-timer events – which might explain why he attended so many – or whether that income contributed to his tax troubles in the 1950s. On the other hand, a player of McAvoy’s modest historical stature would presumably have commanded far lower fees than the likes of Snider and McCovey, if he were paid at all. “Snider and McCovey Guilty on Tax Charges,” Tampa Bay Times, posted July 21, 1995, and updated October 4, 2005; https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1995/07/21/snider-and-mccovey-guilty-on-tax-charges/.

58 “Al Mattern Honored; Photo in Hall of Fame,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 21, 1955: 24; Hans Tanner, “Athletes of Old Days Reminisce,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 19, 1952: 25; “Rochester Americans Hockey” (advertisement for old-timers event), Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 28, 1972: 3D.

59 “Rite for Maranville Today,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, January 9, 1954: 16.

60 “McAvoy Recalls Mack as ‘One of the Nicest,’” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 9, 1956: 34.

61 Henry W. Clune, “Seen and Heard,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 7, 1954: 23.

62 “Mrs. Thereca [sic] M’Avoy, Church Pioneer, Dies,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, February 22, 1951: 23; “McAvoy, George B.,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 3, 1968: 6A.

63 Bill Beeney, “A Signal Experience,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, May 30, 1972: 1C.

64 Bill Reddy, “Keeping Posted,” Syracuse Post-Standard, July 9, 1973: 17.

65 “Wickey McAvoy Dies at 79.”

66 Sporting News contract card, accessed online in June 2024, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/152990/rec/7; David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, Jordan A. Deutsch, The Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1982): 102, https://archive.org/details/sportsencycloped0005neft/page/102/mode/2up?q=%22wickey+mcavoy%22&view=theater; Joseph L. Reichler, The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988): 1227, https://archive.org/details/baseballencyclop00jose_0/page/1226/mode/2up?q=%22wickey+mcavoy%22. Oddly, Macmillan’s 1974 edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia gives July 1 as the date: https://archive.org/details/baseballencyclop00base/page/630/mode/2up?q=%22wickey+mcavoy%22.

67 “McAvoy, James E. (Wickey),” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, July 8, 1973: 6C. As of June 2024, McAvoy’s clip file at the Giamatti Research Center at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum didn’t include a copy of his death certificate. Thedeadballera.com, a website that includes an archive of ballplayers’ death certificates, didn’t have a copy either. Also, McAvoy’s gravestone lists only his years of birth and death, not the dates.

68 “Obituaries,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1973: 18. The other two obits in that week’s issue, for former flying ace and auto racer Eddie Rickenbacker and former college basketball player Bill Simonovich, both include specific dates of death.

69 “McAvoy, James E. (Wickey).”

Full Name

James Eugene McAvoy

Born

October 20, 1894 at Rochester, NY (USA)

Died

July 6, 1973 at Rochester, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.