Washington Senators II team ownership history

This article was written by Andrew Sharp

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

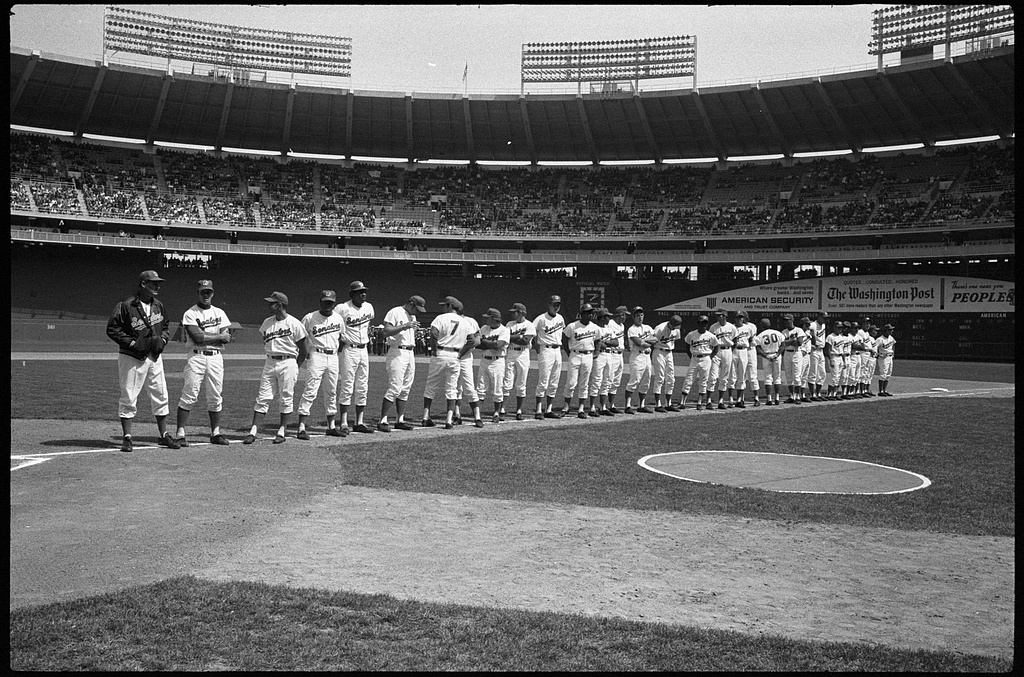

The Washington Senators line up on the field for Opening Day festivities, April 5, 1971, at Robert F. Kennedy Stadium in Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection.)

- Related link: Click here to read Part I of the Washington Senators team ownership history, on the original team from 1901-1960

The franchise that became known as the expansion Senators had an 11-year run in Washington, from 1961 through 1971, before moving to the Dallas-Fort Worth area and becoming the Texas Rangers. The expansion team, created as soon as the original Senators departed for Minnesota, essentially had three sets of owners. None of them could make the team a contender. The last, Robert E. Short, borrowed heavily to purchase the team and subsequently convinced his fellow owners he couldn’t survive financially in Washington.

After 60 seasons as one of the charter members of the American League, the original Washington Senators franchise received permission on October 26, 1960, to relocate. Senators President Calvin Griffith had been increasingly anxious to move after he and his sister became majority owners following the death of their uncle, Clark Griffith, in October 1955.

After 60 seasons as one of the charter members of the American League, the original Washington Senators franchise received permission on October 26, 1960, to relocate. Senators President Calvin Griffith had been increasingly anxious to move after he and his sister became majority owners following the death of their uncle, Clark Griffith, in October 1955.

Even after plans for a new multipurpose stadium were approved in September 1958, Griffith remained noncommittal about staying in Washington.1 When the site in the Southeast section of the city was chosen for what was to become District of Columbia Stadium, Griffith said he preferred a location in the far Northwest part of D.C., an upscale area with a substantial white population. After winning a May 1959 court challenge to his right to leave town, Griffith had stated that “moving the Washington franchise is not my intention.”2 Yet as the 1959 season ended, Griffith formally notified the president of the American Association that the Senators would move to Minneapolis, which had been home to a minor-league American Association team.3 Griffith soon learned that at least five AL owners would veto any move, however, so he did not seek a formal vote. The Senators would remain in Washington for the 1960 season.

The opposition of other owners was a combination of tradition, sentiment, and fear: They recognized the value of having the president of the United States throw out the “first pitch” at the season’s opening game in Washington. Joe Cronin, the American League president, was a former Senators player and manager who had married Clark Griffith’s niece. The most important consideration, however, was the fear that abandoning Washington would prompt Congress to revoke Organized Baseball’s exemption from the antitrust laws.4

That fear was intensified by Branch Rickey‘s proposed Continental League, whose eight teams would include one in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Under pressure to expand or face such competition, major league owners met in August 1960 and agreed with Rickey to add two teams to each league. The National League, acting first, had given itself until the 1962 season to re-establish its presence in New York and add a team in Houston. American League owners chose to act more quickly and voted on October 26 to add Minneapolis-St. Paul and Los Angeles for the 1961 season. The catch was that Minnesota’s Twin Cities would not be saddled with an expansion team, but would inherit the relocated Senators, giving Griffith what he had sought the year before. An expansion team would be placed in Washington.5

The AL owners voted on November 17 to award the new Washington franchise to a group of 10 investors led by Elwood R. “Pete“ Quesada, a World War II general and early military aviator who later became the first head of the Federal Aviation Administration. Quesada had competition from groups headed by John J. Bergen, chairman of the company that controlled New York’s Madison Square Garden, and by Edward Bennett Williams, a prominent Washington lawyer and the future owner of the Baltimore Orioles.6

The ownership group was incorporated as “Senators, Inc.,” leaving no doubt the new team would retain the old team’s name.7 Each of the 10 investors had an equal share. Over the next two years, it was reported that the 10 investors had put up as much as $300,000 each for the franchise.

Quesada was married to the granddaughter of publisher Joseph Pulitzer. She had inherited part of the family fortune. After a 25-year career in the military, Quesada had been an executive at Lockheed Aircraft before President Dwight Eisenhower chose him as the first administrator of the newly established FAA.

Quesada was married to the granddaughter of publisher Joseph Pulitzer. She had inherited part of the family fortune. After a 25-year career in the military, Quesada had been an executive at Lockheed Aircraft before President Dwight Eisenhower chose him as the first administrator of the newly established FAA.

In his first two days as team president, Quesada hired Ed Doherty, president of the American Association, as his general manager and Mickey Vernon, the popular Griffith-era first baseman, as manager. Eleven days into the Quesada ownership, the team acquired its first two players in the draft of minor leaguers.

On December 14, 1960, at American League offices in Boston, representatives of the Senators and the Los Angeles Angels, the other expansion team, each picked 28 players from a pool of those left unprotected by the eight existing AL teams. Washington was represented by Doherty, Vernon, and farm director Hal Keller.8 The owners of the expansion teams each had to spend $2.25 million to participate in the draft.

The existing teams were required to expose seven players from their August 30, 1960, active rosters and eight others from their 40-man rosters. The price was $75,000 each for the 28 players Washington drafted from this list. None of the existing teams was allowed to lose more than seven players. Washington and Los Angeles each were required to select 10 pitchers, then two catchers, six infielders, and four outfielders. The teams also could pay $25,000 each for a nonroster player from the eight existing franchises. Washington ended up selecting three such players for a total of 31.

On April 10, 1961, President John F. Kennedy attended the season opener along with a crowd of 26,750 at rickety Griffith Stadium. After a surprising start in which the team split its first 60 games, the expansion Senators began performing as had been expected. The team ended in a tie with the Kansas City Athletics for ninth place at 61-100. The Senators drew just 597,287 fans, trailing the 10-team league in attendance. (The old Senators had drawn 743,404 with an improved team in 1960.) The final game at the old park attracted just 1,498. The Senators lost to the ballpark’s previous occupants, the Minnesota Twins, 5-1.

Quesada reported in January 1962 that Senators, Inc. had lost nearly $250,000 during its first year of operation. He told the first stockholders meeting in February that the team had hoped to draw 800,000 fans in the first season, which would have produced an operating loss of just $60,000. But the board had good reason to be optimistic.9

Despite the poor attendance the first season, the opening of a new ballpark raised hopes for better attendance in 1962. In the fall of 1961, the National Football League’s Washington Redskins moved into the new multipurpose D.C. Stadium, next to the National Guard Armory. The stadium, paid for by the federal government at a cost of nearly $24 million, had 45,000 seats for baseball. On September 29, 1961, Quesada signed a 10-year lease to use D.C. Stadium. The rental fee would be 7 percent of the gross gate receipts. The Senators would get a third of the concession money.10

The Senators played the season’s opener in their new ballpark on April 9 before President Kennedy and a capacity crowd. A Nats victory over the Tigers was soon followed by a 13-game losing streak.11 By the All-Star break, the team was 26-54, deep in last place.

In August 1962, Quesada told a reporter he was on the verge of making wholesale changes in management, making it clear that the jobs of Doherty and Vernon were jeopardy. The owner said the team lacked punch, especially at first base and third base. The incumbent first baseman, Harry Bright, who had homered in that day’s game, confronted Quesada in the clubhouse after reading his comments.12 Although Bright tied for the ’62 team lead in homers (with 17), he was traded in the offseason.

As the season ended, Quesada asked Doherty for his recommendations about how best to improve the team. The GM told him Vernon should be fired. Instead, Quesada fired Doherty and extended Vernon’s contract for another year. A replacement GM wasn’t hired until November 21, when the job went to George Selkirk, the former Yankee who had served as a minor-league manager, coach, and front-office executive for three organizations. Shortly after Quesada had said that a new GM would have authority over baseball operations — “with my approval, of course”13 — Quesada promised Selkirk a free hand over player personnel and contracts.

Although 1962 was another dismal season on the field, the new stadium helped boost Senators attendance 22 percent to 729,775, an average of just 40 fans a game fewer than the Boston Red Sox drew at Fenway Park. Still, Senators, Inc. lost $125,000 in 1962.

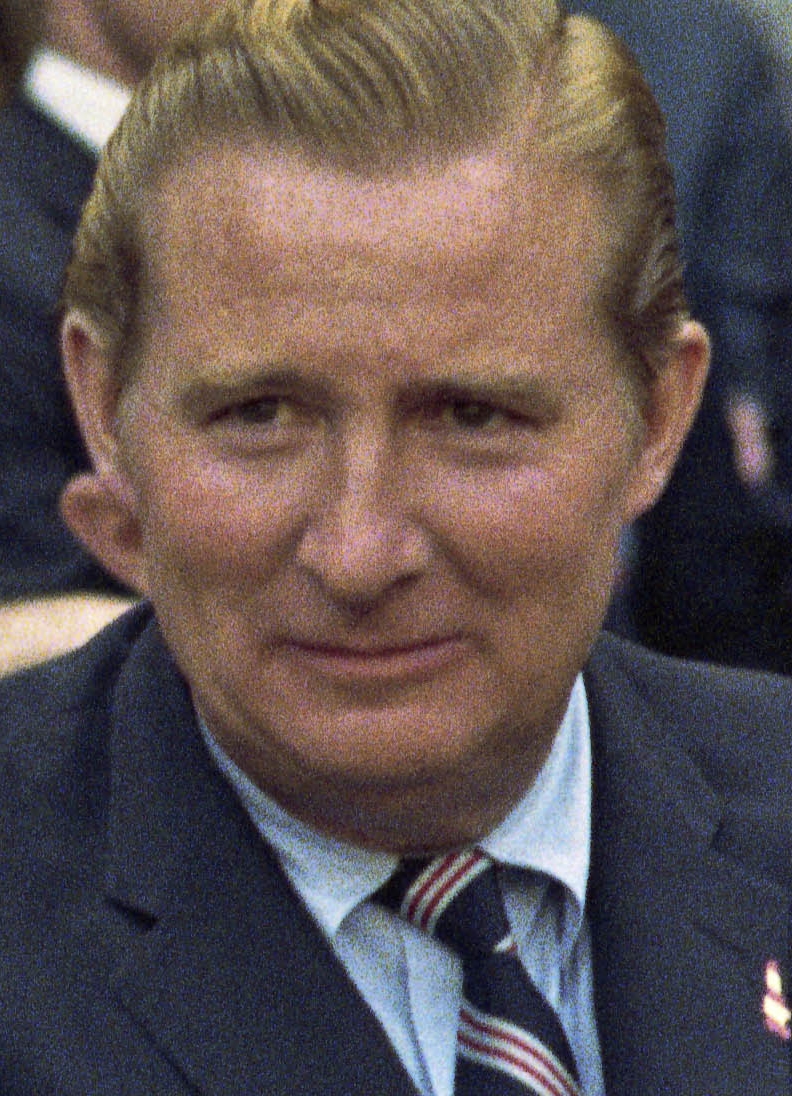

President John F. Kennedy laughs as Washington Senators catcher Ken Retzer grasps his hand during opening day of the 1963 baseball season at D.C. Stadium in Washington, D.C. (Robert Knudsen, White House Photographs, John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.)

In January 1963, Quesada issued a much-ballyhooed three-part report on the team’s first two seasons. Among other complaints, he was sharply critical of the coverage of the team in the city’s three daily newspapers. A week after the release of the third part of his report, Quesada sold his shares, as did four of the other 10 original investors, to the remaining five. One of the five, James M. Johnston, an investment banker, was named chairman of the board. The deal was arranged quickly to counter an offer of $5 million for the team made by former Cleveland Indians stockholder Nate Dolin and longtime baseball executive Bill Veeck, who had been rumored for months to be interested in buying the Senators. Johnston said he and his partners stepped in to ensure that the team remained in local hands.

Eight of the 10 original investors in the franchise had agreed to sell to Veeck and Dolin for a reported $5 million. Johnston and James Lemon were the holdouts. They enlisted original shareholder George Bunker, president of Martin Marietta, to join them in a counteroffer, which the others accepted. Five years later, Veeck said he had made an offer of $5.75 million for the team in 1967 “and they turned me down. Now I hear the price is up by a couple of million.”14

When the dust cleared, the five remaining stockholders in Senators, Inc. were Johnston and James H. Lemon with 60 percent, Bunker with 20 percent and auto dealer Floyd Akers and Agnes Meyer, widow of the Washington Post’s owner, with 10 percent each. She was represented on the board of directors by John W. Sweeterman, a Post executive.15

The new board chairman, Johnston, a North Carolina native, had been a pilot in France during World War I as a young Army lieutenant. He had graduated from the University of Illinois after two years at the University of North Carolina, where years later he created a foundation that to this day provides need-based scholarships. Lemon was Johnston’s business partner.

Johnston and Lemon had been in investment banking together in Washington since 1926. Johnston told the Washington Post’s Bob Addie that he had been broke a few times. He bounced back to the point that he “once wrote a personal check for $30,000,000,” Addie reported.16 The two partners had tried to buy a controlling interest when the expansion franchise was created, Johnston said, but he and Lemon were each limited to a 10 percent share.

Lemon was born and raised in Washington and attended Princeton University, where he played basketball, leading the 1924-25 Tigers in scoring. That team was among the nation’s best with a 21-2 record. To earn extra money, he coached the George Washington University’s men’s basketball team in 1925-26 and 1926-27.17

Johnston told Selkirk and Vernon that they would “have wider authority than they had under the Quesada regime.” He told the Washington Post’s Shirley Povich that “he and his fellow owners would adopt a hands-off policy on the operations of the team, except fiscally.”18

In May, Selkirk was allowed to hire former Dodgers star Gil Hodges to replace Vernon as manager. The expansion team had its worst season on the field, losing 106 games, and at the box office, drawing a league-low 535,604 in 1963. Those results produced a loss of $1.2 million. Although the Nats escaped the cellar in 1964, attendance barely topped 600,000.

In January 1965, Johnston and Lemon consolidated their control of the team by paying an estimated $2 million for the 40 percent held by Bunker and Akers. Having previously acquired the shares of Agnes Meyer, Johnston and Lemon now had complete ownership of the Senators, each owning 50 percent.19

On the field, the Senators gradually improved a bit under Hodges, but attendance showed scant improvement: a league worst 576,260 in 1966. The disappointing figure prevented the Armory Board, which operated D.C. Stadium, from making principal payments on the bonds that had been issued for construction. The board was paying $800,000 annually in interest on the bonds. The stadium’s deficit in 1965 was $601,000.

Senators, Inc. losses since the team’s creation had totaled more than $2 million, but Johnston said in late August 1966 that the team was “not for sale as of now. That doesn’t mean I won’t change my mind six months from now or 10 years from now. In the investment business, ‘never’ is not in your vocabulary.” But he insisted, “Nobody likes to lose money.”

Johnston extended the contracts of Selkirk and Hodges in early January 1967. Selkirk appreciated the freedom the owner gave him in baseball matters. “He doesn’t go for the second guess,” Selkirk said. “I make trades on my own. He’s a wonderful man to work for.”20

By early fall, however, Johnston had fallen ill, so co-owner Lemon took over as the team’s chief executive. A sixth-place finish in 1967 helped attract 770,868 fans — an increase of almost 195,000 over 1966. But as soon as the season ended, Hodges resigned to become manager of the New York Mets. Then, on December 28, Johnston died of cancer. Lemon succeeded him as chairman of the board and signed off on Selkirk’s choice of former Griffith-era Senators slugger Jim Lemon — no relation to the owner — as the new manager.

In January 1968, Veeck made it known he was still interested in buying the team, and rumors persisted during the season, especially as the Nats reverted to form and fell into the cellar, that the team indeed was for sale. At season’s end, Lemon said he didn’t have enough money to acquire the ownership stake of his late partner and so he was seeking a buyer. “The chips are too high,” he told Morris Siegel of the Evening Star.21

Minnesota businessmen Robert E. Short and Jeno F. Paulucci, inventor of the pizza roll, put in a bid for the Senators. So did entertainer Bob Hope and a St. Louis group that included Stan Musial. Another group from Dallas-Fort Worth expressed interest. The asking price was reported to be $10.5 million.22

Minnesota businessmen Robert E. Short and Jeno F. Paulucci, inventor of the pizza roll, put in a bid for the Senators. So did entertainer Bob Hope and a St. Louis group that included Stan Musial. Another group from Dallas-Fort Worth expressed interest. The asking price was reported to be $10.5 million.22

Short, a trucking and hotel magnate, had previously owned basketball’s Minneapolis Lakers and moved the team to Los Angeles before selling it for $5.2 million. Short’s profit was at least $3 million. According to Shelby Whitfield, later the Nats broadcaster, Short had offered to buy the Senators in 1965, but Johnston refused. Lemon, Whitfield wrote, had gone as far as to give Bob Hope a verbal option to purchase the team.23

At the time, Short was the treasurer of the Democratic National Committee. He had run unsuccessfully for Congress in 1946 and for Minnesota lieutenant governor in 1966. He also had been a major fund-raiser for Hubert H. Humphrey’s presidential candidacy. Short was familiar with Washington, having attended Georgetown University Law School and served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the Justice Department.

Lemon was insisting that new ownership keep the team in D.C. and wanted to retain a 10 percent share of stock. Finally, he agreed to sell to Short alone for $9.4 million and an option to buy back up to 20 percent by the spring of 1969. Paulucci refused to sign for the needed loans, and pulled out. The final agreement on the sale was reached on December 3, 1968. Lemon exercised his option to keep a 10 percent share (for a reported $1.1 million) and remained on the board. Short became owner when the deal closed on January 28, 1969. Under baseball rules, Short had to sell his 399 shares of Twins stock.

Short fired GM Selkirk and manager Lemon as soon as the sale was finalized. (Selkirk was offered a lesser role but declined.) The new owner made it clear he would be making player transactions himself, although he eventually brought back the team’s original GM, Ed Doherty, as an adviser. During the spring of 1970, however, even Doherty was sent packing. He remained a Nats scout until he suffered a stroke later that year.24

It wasn’t long before Short began making ominous statements about Washington’s commitment to keeping a team. He demanded that fences be built around the outer parking lots of the recently renamed Robert F. Kennedy Stadium, implying that the area was unsafe. He blasted fans for their lack of support. “Look at last year’s attendance. I can round up a girls’ team and draw 500,000,” Short said in February. “If they don’t want the Senators here … then Dallas or Milwaukee or some other places do.”25 Coincidentally (or not), two exhibition games at the end of spring training, scheduled to be played in Louisville, were transferred at Short’s suggestion to Arlington, Texas.

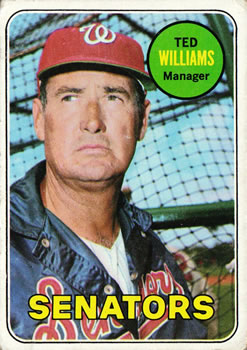

Short said he talked to at least two of a group that included Jackie Robinson, Elston Howard, Maury Wills, and Monte Irvin about becoming the majors’ first black manager. Then he hired somebody no one thought he could: Ted Williams. Short apparently made an offer Williams couldn’t refuse: $65,000 a year for five years, a $15,000-a-year hotel suite, an unlimited expense account, a title as vice president and an option to buy 10 percent of the team for $900,000. He was given the choice of joining the front office after a season if he tired of managing.26

Short had enlisted the help of AL President Cronin to persuade Williams to take the job. Cronin had brought Washington its last pennant as player-manager in 1933. He knew Williams well. Both were together for many years in Boston. Cronin told Williams baseball needed a strong franchise in Washington, but even more important, baseball needed Ted Williams. The Splendid Splinter seemed to have an itching to show how much he could improve Nats hitters, too.27

The arrival of Williams brought unmistakable excitement to the Senators’ 1969 season. He didn’t disappoint. Nearly all the hitters improved as Williams led the team to 86 victories and was voted AL Manager of the Year. Washington fans showed they would support a decent product on the field, boosting attendance to a franchise-high 918,106 despite Short’s big hike in ticket prices. (Mezzanine box seats went from $3.50 to $5, for instance.) The Senators’ attendance increase was the highest in the league.

The arrival of Williams brought unmistakable excitement to the Senators’ 1969 season. He didn’t disappoint. Nearly all the hitters improved as Williams led the team to 86 victories and was voted AL Manager of the Year. Washington fans showed they would support a decent product on the field, boosting attendance to a franchise-high 918,106 despite Short’s big hike in ticket prices. (Mezzanine box seats went from $3.50 to $5, for instance.) The Senators’ attendance increase was the highest in the league.

Still, Short claimed to have lost about $600,000 in 1969. In an interview with The Sporting News publisher C.C. Johnson Spink, he blamed the red ink on “a large outlay for promotion, some fat bonuses to youngsters and also making good on the rest of George Selkirk’s contract.”

Short also said he was paying a hefty amount of interest on what he borrowed to purchase the team. “I hate to use to use the word bankrupt,” he told Spink, “but if it weren’t for television and radio income, that’s the way it would be.”

Again, Short made clear how much support he expected from Washington fans. “If you can’t excite a million people in your club, then you had better start looking around.” In fact, half of the 24 major-league teams failed to reach a million in attendance in 1969.28

At end of the year, Short began exploring a run for governor of Minnesota. By May 1970, informal polls showed him as the top choice among the state’s Democrats. Short, however, was put off by, in his view, the Minnesota governor’s meager salary — $27,500 a year — and the fact that he would have to give up control of the Senators if he was elected. By June, he had decided against running.29

Neither Williams nor his team could repeat 1969’s success. The Senators were struggling along, eight games under .500 in mid-September when the bottom fell out. The Nats finished the season on a 14-game losing streak. “I thought we would do as well or better” than the year before, a disappointed Short said. He made it plain he planned a massive roster turnover.30

Yet despite another 20 percent increase in ticket prices, the 1970 Nats still drew 824,789 fans, the second highest total in their 11-year existence.

On October 9, Short made what turned out to be a disastrous trade with the Tigers, sending Detroit shortstop Ed Brinkman, third baseman Aurelio Rodriguez, and pitchers Joe Coleman and Jim Hannan for a washed-up Denny McLain and three journeymen. McLain lost 22 games for the 1971 Senators. Coleman won 62 games in his first three seasons in Detroit as he, Brinkman, and Rodriguez became key parts of the 1972 AL East champion Tigers. The next May, Short traded closer Darold Knowles and first baseman Mike Epstein to Oakland, thus putting five former Nats stars in the 1972 American League Championship Series.

“I had to do something. I’m going broke,” Short said in defense of the McLain trade. “He will put people in my ball park.” The general consensus at the time was that the Tigers got by far the best of the deal and that Short had secured the support of Tigers ownership to move his team. Williams, who did not attend the press conference announcing the trade, agreed the price was just too high.31

Meanwhile, Short was in disputes with Pompano Beach, Florida, where the Nats trained, and with the D.C. Armory Board over rents and facilities. He visited training sites in Arizona, threatening to leave Florida if Pompano Beach didn’t make improvements. He told the Armory Board he wanted a rent deal for RFK Stadium similar to Milwaukee’s, under which he would pay just $1 a year until the team reached one million in attendance.

In testimony before a congressional committee the previous fall, Short said he had lost $1.8 million in his first two years as Nats owner. “I can’t maintain the team under the present condition. … I don’t want to move to Dallas or Toronto. I want the team to stay in Washington,” Short told the committee.

Although Short never made the team’s budget public, he offered the congressional committee a breakdown of what he said were his annual stadium expenses: $200,000 for rent, $100,000 for grounds crew, $100,000 for police, and $100,000 for lighting. He said he received about $200,000 from concessions and parking and ended the year earning about $700,000 less in stadium revenue than other team owners.32

Short said he’d be willing to sell, but added ominously, “Everybody keeps saying baseball must have a team in Washington. I don’t happen to agree.”33

Not everyone was buying the pleas of poverty from a man who continued to fly everywhere in his own Lear jet. “Short’s woes appear largely of his own making,” The Sporting News wrote in an editorial. “If he’s as sharp as he was once reported to be, his Washington difficulties shouldn’t pose too much of a challenge.”34

The NFL’s Redskins paid the Armory Board $400,000 in rent for three exhibition games and seven regular-season games, the Washington Post’s Addie reported in February, while the Senators were charged just $150,000 — not the $200,000 Short claimed — for 79 home dates in 1970. As for Short’s offer to sell, “Oddly, he has been stipulating that the club remain in Washington, something which he has been accused of being less than zealous about,” Addie wrote.35

Whitfield, the Senators radio and TV voice in 1969 and ’70, described Short as “an intimidating, domineering person” who bought the team as a tax writeoff with other people’s money. Before Short gave up on D.C., radio announcers were told to report that crowds were bigger than they were and that the weather was good “even if the floodwaters were lapping the sides of RFK Stadium.” Once the owner had made up his mind to move, however, Whitfield was told not to mention a really large crowd.36

When spring training began in 1971, the Senators had undergone a 50 percent roster turnover. Among the new faces was Curt Flood, lured back from Europe by Short with a $110,000 contract that contained a provision that allowed Flood to continue his suit challenging the reserve clause. Short sent three minor leaguers to Philadelphia, the team to which Flood had been traded, in a complicated transaction that raised eyebrows and had to be approved by Commissioner Bowie Kuhn.

The Nats owner promised Flood that he would not be traded and that he would make him a free agent after the 1971 season, if Flood wanted out. None of this was in writing, of course.37 A year off, however, took its toll on Flood’s skills. After a horrible start, he abruptly left the team in early May and returned to Europe.

By June 1971, Short insisted he needed help from the league to avoid bankruptcy. The Armory Board was threatening to turn the stadium’s lights off if $160,000 in back rent wasn’t paid. “There is no way Bob Short can operate the Senators in Washington any longer,” Short said, referring to himself in third person. “I never intended to move,” he told an owners meeting in Detroit, “but that doesn’t mean I won’t.”38

The man who moved the original Senators to Minnesota chimed in on Short’s behalf. Calvin Griffith, who years later famously said, “Black people don’t go to ballgames. … We came here because you’ve got good, hardworking white people,” argued that Washington didn’t deserve a team. Keeping one there is “stupid,” Griffith said, according to Merrell Whittlesey of the Evening Star.39

In a moment of candor, Short paid a grudging compliment to the Senators’ fan base. “You get 800,000 people to pay our prices to see our team in that stadium and you’ve gotta believe they’re dedicated,” he told a Sports Illustrated writer.40

At an August meeting, Short told fellow owners he needed more than $3 million by October 31 to make a payment of principal and interest on the loan he negotiated to purchase the Senators. Veeck, who met with Short in mid-September, and Bob Hope were willing to pay $7.5 million for Short’s share of the team, but he wanted $12.4 million to cover what he claimed he had paid for the team and for the money he had lost. After delivering a report on the situation, Cronin said, “Our primary objective is to get some new financing for Short. If that fails, we will try to seek new local ownership in Washington.”41

Kuhn, who worked as a scoreboard operator at Griffith Stadium as a youth, started looking for a corporation willing to buy the team. The Armory Board, meanwhile, came up with a compromise plan that it said would save Short $125,000 a year in rent. Short, whose lease was expiring, said it was too late.

Chicago White Sox owner John Allyn contacted Joseph B. Danzansky, president of the D.C. Board of Trade and the head of a local supermarket chain, to ask if he could come up with an offer for the team. On September 21 in Boston, Danzansky appeared alone before the owners and their attorneys with an offer of up to $9.3 million — $2.7 million in cash and a loan of $6.6 million — for Short’s share of the team. The offer was rejected as too risky.42 The mayors of Dallas and Fort Worth, meanwhile, were among a nine-person delegation from Texas that made a presentation for the team. Short presented detailed financial figures and projections, which obviously had taken months to prepare, in support of relocating his franchise to Texas.

In effort to round up support, Short persuaded Williams to call Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey to argue in favor of the move. Charles Finley, owner of the Oakland Athletics, initially an opponent, tried to enlist an airline executive to make an offer for the team. When that failed, Finley voted with the majority, as did the hospitalized Angels owner Gene Autry. That gave Short the support he needed.43

After meeting for more than 13 hours, the owners voted 10 to 2 to allow Short to move. Allyn of the White Sox and Jerold Hoffberger of the Orioles were the “no” votes. Hoffberger was fearful, probably unnecessarily, that a National League team might move into Washington, cutting into the Orioles’ market. Allyn believed the team could have been sold and kept in Washington, if Short’s asking price had not been unreasonably high. He said the Arlington Park Commission, a quasigovernment entity in Texas, would advance Short $7.5 million, either as a 10-year no-interest, loan or as an advance payment on broadcast rights. Allyn said that money was essentially taxpayer dollars bailing out Short.44

“I don’t think much could have been done that would have convinced (Short) to stay. … He was hearing siren songs, beautifully sung,” Kuhn told the Washington Post years later.45

Another scathing editorial in The Sporting News blasted Short and his fellow AL owners once they had approved his move to Texas. “For acquiring mountainous debt he couldn’t pay, for jacking ticket prices to the highest level in baseball, for bungling his self-appointed task as an amateur general manager, for pleading poverty and begging his landlord to bail him out, Short has been miraculously rewarded.”46

The year after Short moved the team to Texas, two Brookings Institution economists, relying on figures Short gave his own accountants, concluded that he had spent just $1,000 of his own money — what it cost to incorporate — to buy the Senators. He borrowed the rest.47 Several members of Congress called for hearings to investigate Short’s finances and introduced bills to revoke baseball’s exemption from antitrust laws, but nothing came of those efforts.

In addition to the disastrous McLain deal, trades that Short declined to make helped doom the Senators. He reportedly turned down the Braves’ offer of Joe Torre for Epstein and Paul Casanova, the Athletics’ offer of a young Catfish Hunter for Epstein, a Mets offer of either Nolan Ryan or Tug McGraw for Ken McMullen, and one from the Twins asking for Brant Alyea in exchange for prospect Graig Nettles.48

Whitfield’s former broadcast partner, Ron Menchine, called the play-by-play of the Senators’ last game in Washington, against the New York Yankees on September 30, 1971. After he made comments critical of the team leaving town, Short (who, lucky for him, wasn’t at the game) called the booth, yelling, “Get him off the air.” Menchine kept talking, knowing he wasn’t going with the team to Texas and had nothing to fear. With the Senators an out away from a final victory, fans stormed the field. The umpires declared a forfeit in favor of the Yankees. The Senators were no more.49

Bucky Harris, the player-manager who brought Washington its only World Series title in 1924, was in the press box for the final game. “It’s a sad day,” he said.50

ANDREW SHARP grew up in the D.C. area as a fan of Washington Senators I and II, and spent 30-plus years in the wilderness as a New York Mets fan before happily regaining a Washington team to support. A retired newspaper editor, he began writing BioProject essays in 2017 and has written SABR’s ownership histories of the Griffith era and the expansion Senators. He charts minor-league games on a freelance basis for Baseball Info Solutions.

Notes

1 Dave Brady, “Cal Griffith Non-Committal on New Park,” The Sporting News, July 20, 1960: 10.

2 Shirley Povich, “‘No Intention to Move Nats,’ Griffith Says,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1959: 11.

3 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Nats Will Shift to Minneapolis, Griff Notifies Doherty and A.A.,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1959: 1.

4 Tom Deveaux, The Washington Senators, 1901-1971 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2001), 207.

5 Associated Press, “A.L. Going Into Los Angeles and Twin Cities in 1961,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 27, 1960: 56.

6 Associated Press, “3 Groups Apply for Washington Franchise; AL Chiefs Ponder Los Angeles Move,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, November 18, 1960: 30.

7 James R. Hartley, Washington’s Expansion Senators (1961-1971) (Germantown, Maryland: Corduroy Press, 1998), v.

8 Andy McCue and Eric Thompson, “Mismanagement 101,” The National Pastime 2011, Society for American Baseball Research, Phoenix: 43.

9 Povich, “Senators in Red by $250,000, but Increase Budget for 1962,” The Sporting News, January 10, 1962: 24.

10 Jay Roberts, “Return to RFK,” Jaybirds Jottings blog, January 17, 2005, jay.typepad.com/william_jay/2005/01/return_to_rfk.html, accessed Dec. 30, 2017.

11 The original franchise was officially the Nationals until after Clark Griffith’s death, even though the team was popularly known as the Senators, thus the shortened nickname, the Nats, which carried over to the expansion franchise.

12 Povich, “Nats’ Vernon, Doherty Face Quesada’s Ax,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1962: 24.

13 Povich, “Nats Rumor Mill Spills Hot Tidbits in Series Chatter,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1962: 25.

14 Associated Press, “Says Senators Are for Sale, but No Takers,” Racine (Wisconsin) Journal Times, September 28, 1968: 10.

15 Povich, “Quesada Cashes In — All Quiet Again Along the Potomac,” The Sporting News, February 9, 1963: 14. Among the original 10 investors who along with Quesada sold their shares were Katharine Graham, Agnes’s daughter and the wife of the Post publisher; Mrs. Robert Levi, wife of a department store owner; George A. Garrett, a former ambassador to Ireland; and banker George Y. Wheeler.

16 Bob Addie, “Financial Wizard Johnston Serene in Nat Red Ink Sea,” The Sporting News, January 23, 1965: 18.

17 goprincetontigers.com basketball all-time records; bit.ly/2zzOXTX, accessed December 26, 2017; gwsports.com/sports/m-baskbl/archive/yearbyyear.html.

18 Povich, Quesada Cashes In.”

19 Addie, “Financial Wizard Johnston.”

20 “Johnston Dons His Santa Suit; New Pacts in Nat Brass Socks,” The Sporting News, January 7, 1967: 26.

21 Merrell Whittlesey, “Lemon Says ‘Chips Too High,’ May Sell Senators Before ‘69,” The Sporting News, October 12, 1968: 17.

22 Whittlesey, “Sale of Nats Near — Ask $10.5 Million,” The Sporting News, November 11,1968: 36.

23 Shelby Whitfield, Kiss It Goodbye (New York: Abelard-Shuman, 1973), 9.

24 Whitfield, 224-225.

25 Short Takes Long Look at Lack of Radio Outlet,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1969: 41.

26 Ben Bradlee Jr., The Kid: The Immortal Life of Ted Williams (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2013), 529.

27 Bradlee, 530.

28 C.C. Johnson Spink, “We Believe” column, The Sporting News, January 17, 1970: 14.

29 Addie’s Atoms column, The Sporting News, June 13, 1970: 16.

30 Whittlesey, “Short Just Won’t Stand Still, Seeks More Nats’ ‘Faces,’ The Sporting News, November 14, 1970: 49.

31 Whittlesey, “Nats Nab McLain to Bolster Sagging Gate,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1970: 11.

32 “Senators Need Help, but Franchise Shift Is Unlikely — Kuhn,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1970: 20.

33 Whittlesey, “Nats Nab McLain.”

34 “Shed No tears for Short,” editorial, The Sporting News, September 14, 1971: 14.

35 “Addie’s Atoms” column, The Sporting News, February 6, 1971: 14.

36 Whitfield, 72-75.

37 Deveaux, 250.

38 Whittlesey, “Senators in Financial Shorts, Seek League Lift,” The Sporting News, July 12, 1971: 27.

39 Ibid.

40 Ron Fimrite, “Bad Case of the Short Shorts,” Sports Illustrated, August 9, 1971, accessed online December 29, 2017, at si.com/vault/1971/08/09/612074/bad-case-of-the-short-shorts#.

41 Edgar Munzel, “Table Gets Bulk of Play at Major Confab,” The Sporting News, August 21, 1971: 5.

42 Danzansky two years later was heavily involved in a nearly successful effort to get the San Diego Padres to relocate to Washington.

43 Whitfield, 236, 240.

44 Jerome Holtzman, “A $7.5 Million Bonanza for Short?” The Sporting News, October 9, 1971: 12.

45 Ken Denlinger, “Washington’s Storied Past Includes Unhappy Endings,” Washington Post, March 3, 1991: D1.

46 “How to Succeed in Baseball,” editorial, The Sporting News, October 9, 1971: 14.

47 Whitfield, 13.

48 Hartley, 106; Deveaux, 250.

49 Hartley, 141.

50 Whittlesey, “Senators Expire Amidst Love for Hondo, Hate — and Forfeit,” The Sporting News, October 16, 1971: 34.