April 22, 1948: Bob Porterfield pitches Newark Bears to Opening Day victory

“No one grows up playing baseball pretending that they’re pitching or hitting in Triple-A.” – Chris Schwinden1

“No one grows up playing baseball pretending that they’re pitching or hitting in Triple-A.” – Chris Schwinden1

Minor-league baseball players dream of the chance to play in the major leagues. Some toil for years and never get the opportunity. Others are there for only a glimpse – a “cup of coffee.”2 Some are destined to be there, others often yearn to return. Their aspirations are the same, even if their stories are often very different. In the Triple-A minor leagues, players are tantalizingly close to the big leagues, often just a telephone call away after a regrettable injury to a major-league player.

To examine the box score of a baseball game, major league or minor league, is to learn in a snapshot exactly what took place on the field of play. The box score as “a condensed statistical summary of a baseball game, traditionally a feature of newspaper sports sections” 3 is as old as the game itself. Historian Melvin Adelman wrote that the first such statistical summary was published in the New York Herald on October 25, 1845, to record the results of “baseball play” between the New York and Brooklyn clubs.4 As the game has evolved, so has the box score and its complexity while remaining essential for the historical record of a game’s statistical results.

The 1948 Triple-A International League season began at Ruppert Stadium with the Newark Bears hosting the Montréal Royals in front of 13,996 fans. Baseball was as popular as ever on this postwar Opening Day in the New York City metropolitan area. Just down the road, 31,000 fans were jammed into Roosevelt Stadium, watching the Jersey City Giants entertain the Toronto Maple Leafs.5 Across the Hudson River at the Polo Grounds, 21,198 fans were watching bitter National League rivals, the New York Giants versus the Brooklyn Dodgers. Just two days earlier, 48,130 fans saw the Dodgers beat the Giants 7-6 to open their season.

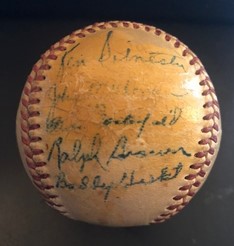

How fitting was the Newark-Montréal matchup to open the season? The New York Yankees had defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the seven-game 1947 World Series. Their Triple-A affiliates were the Bears and the Royals, respectively. The account that follows reveals the many stories behind the game’s box score and the names on a signed baseball from that very season.

Montréal manager Clay Hopper named Hank Behrman to start for the Royals. A Brooklyn native, Behrman had debuted for the Dodgers in 1946 (11-5, 2.93 ERA), splitting the 1947 season between Pittsburgh and Brooklyn.6 Back with the Royals, his career seemed to be one always filled with promise. SABR biographer Rob Edelman noted, “His reputation as an irresponsible young man who was not reaching his potential as a frontline hurler now was firmly in place among the Dodgers higher-ups.”7

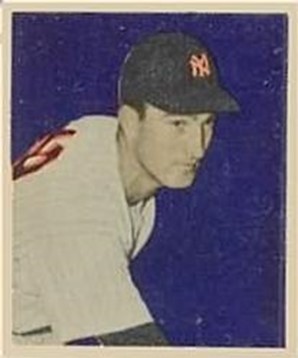

For his debut game as Bears manager, Bill Skiff picked Bob Porterfield to start. Porterfield’s star was on the rise and Triple-A baseball seemed merely to be one more stop on the road to the big leagues. Porterfield’s 1947 record at Class B Norfolk (17-9, 2.37 ERA, 208 strikeouts in 239 innings) had the Yankees dreaming of a starting pitcher to join Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds, and Eddie Lopat.

With the game scoreless in the bottom of the third inning, Behrman committed the cardinal sin of pitching by walking opposing pitcher Porterfield. Johnny Lucadello, formerly of the St. Louis Browns, lined a double to center with two outs. Second baseman Jimmy Bloodworth took the relay from the outfield, but his throw to the plate sailed over catcher Cliff Dapper’s head, allowing Porterfield to score for a 1-0 Bears lead. The Royals error was a portent of things to come.

Behrman got into trouble again in the fourth when he walked the first two batters, Joe Collins and Frank Colman. After Ken Silvestri grounded into a double play, Ted Sepkowski lined a single to right, scoring Collins for a 2-0 Bears lead.

The Royals got back into the game in the fifth when John Simmons walked and Bloodworth homered into the left-field bleachers to tie the score. The Royals threatened to score more when Walter Sessi and Dapper hit successive singles and Chuck Connors was intentionally walked to load the bases. Porterfield ended the threat by snaring Louis Welaj’s liner for the third out.

Any chance the Royals had to score a game-leading run in the ninth inning was erased by “a piece of rock-headed base running.”8 Bobby Morgan opened the inning with a single to center. Behrman popped a bunt to the right of home plate, but when Porterfield, Silvestri, and Colman collided, the ball was dropped and Morgan was forced out at second. One problem. Behrman forgot to run and the Bears had an easy double play.

After Behrman was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the top of the 11th inning, Bud Podbielan came in to pitch the bottom half and the Royals defense proceeded to fall apart behind him. First baseman Connors booted Collins’s slow roller. Colman, the next batter, bunted toward first. Connors fielded it cleanly and attempted to start a double play, but a wild throw to second allowed Collins to advance to third. Connors had an immediate opportunity to make amends when Silvestri grounded to first. He fielded it cleanly, but Dapper dropped the perfect throw to the plate and Collins scored the winning run.

Porterfield’s Triple-A debut was a success and the New York Times box score tells us the story.9 Porterfield gave up eight hits and walked six Royals, but seven strikeouts and timely pitching stranded 10 runners. Perhaps Behrman also deserved a better fate. After all, the Bears collected only four hits all afternoon. Five errors, three by Connors, were just too much for Royals pitching to overcome.

Porterfield’s Opening Day performance propelled him to near-perfection in the first month of the season. Five days later, a bid for a no-hitter was spoiled by ex-Yankee Russ Derry’s eighth-inning single as Porterfield shut out Rochester 3-0. On May 2 Porterfield won his third straight game and second shutout in a row, yielding only three hits to Buffalo in a 4-0 win. Speculation started. When would Porterfield make his major-league debut with the Yankees?10

By no means was Porterfield done. On May 9 he shut out Rochester again on three hits after holding them hitless over the first six innings. On May 16 Toronto finally broke his streak of 36 consecutive shutout innings, but Porterfield won nonetheless, 10-3.

The back of Porterfield’s baseball card got it right. He had set the International League on fire with his pitching. By the time Porterfield was called up by the Yankees in early August, he had compiled an impressive record in completing 20 of his 22 starts – 15-6, 2.17 ERA. Behrman also earned another shot with the Dodgers, compiling an 8-2, 2.55 ERA record before his June recall. It was his last shot with the Dodgers, who sold him to the Giants before the 1949 season.

The box score documents the historical record of a single game without revealing where a baseball career might be headed. Chuck Connors, batting sixth in the Royals lineup, went hitless in the game. His major-league debut for the Dodgers was one year away and not the most auspicious of occasions. On May 1, 1949, at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers trailed the Phillies 4-2 in the bottom of the ninth inning. The Brooklyn native pinch-hit for Carl Furillo and grounded into a game-ending double play, his only career at-bat in a Dodgers uniform.11

Then there was the diminutive center fielder Al Gionfriddo, leading off for the Royals. He debuted with the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1944, but was traded to the Dodgers in 1947, playing a utility role for the balance of the season. He will always be remembered for just one play, in the sixth game of the 1947 World Series at Yankee Stadium. Gionfriddo’s racing, twisting catch of a fly ball to deep left-center off the bat of Joe DiMaggio in the sixth inning helped save the game for the Dodgers to force a decisive Game Seven.12 DiMaggio’s rare emotion as he kicked the dirt near second base was seen by many in the first televised World Series. SABR biographer Rory Costello captured the essence of Gionfriddo and the occasion. “At root, though, is the appeal of a hard-working little guy’s moment in the sun.”13

What ever happened to Gionfriddo? He toiled for eight more minor-league seasons including four with the Montréal Royals. In fact, his famous catch in that World Series, forever part of baseball history, was the last fly ball he ever caught in the last game he ever played in the major leagues.

As for Porterfield, he made his major-league debut for the Yankees on August 8, 1948, at Cleveland Stadium. Porterfield pitched 6⅔ innings, but lost to the Indians, 2-1. There would be many more box scores to follow. His injury-filled career (87-97, 3.79 ERA) included stops in Washington, Boston (Red Sox), Pittsburgh, and Chicago (Cubs). As SABR biographer Warren Corbett put it, “Bob Porterfield climbed the mountain and enjoyed the view from the top, if only for a short while.”14

Author’s note

Thanks to a generous next-door neighbor who was a laundryman for the 1948 Newark Bears, the baseball, signed by 12 players, is now a prized possession of the author.15 Six of those players, including the battery of Bob Porterfield and Ken Silvestri, were starters in the Opening Day lineup. Most notably, the ball was signed by Bob Keegan, who made his major-league debut in 1953 as a 32-year-old rookie pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. Keegan left his mark in baseball’s record book by pitching a no-hitter against the Washington Senators in 1957.16

Are there other stories behind the autographs on a baseball? Pitcher Hank LaManna, shelved by a bad thumb, had a fleeting glimpse of the major leagues in the early 1940s with the Boston Bees/Braves (6-5, 5.24 ERA), never to return. Catcher/outfielder Buddy Heslet, holding out on a contract until days before the opener, was not so fortunate.17 He toiled for 14 seasons in the minor leagues without ever realizing the dream of playing in the big leagues. Stories often repeated, but never the same.

Sources

The author accessed Baseball-Reference.com for data/information about individual players. Play-by-play detail was obtained from the Montreal Gazette.18 The Bob Porterfield baseball card is from the 1949 Bowman series (#3 of 240) obtained from the Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 John Feinstein, Where Nobody Knows Your Name (New York: Doubleday, 2014), 10. Schwinden pitched in seven games for the New York Mets in 2011/2012 for a career mark of 0-3, 6.98 ERA in 29⅔ innings pitched.

2 Paul Dickson, The Dickson Baseball Dictionary, 3rd Edition (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), 230. A cup of coffee is a brief trial in the major leagues by a minor league player.

3 Dickson, 131.

4 Melvin L. Adelman, “The First Baseball Game, the First Newspaper References to Baseball, and the New York Club: A Note on the Early History of Baseball,” Journal of Sport History 7, no.3 (Winter 1980): 132.

5 Cy Kritzer, “Int Opens 65th Season with 87,735 Paid Gate,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1948: 20.

6 On May 3, 1947, Behrman, Kirby Higbe, Dixie Howell, Gene Mauch, and Cal McLish were traded to the Pirates in exchange for Al Gionfriddo and $100,000. By June 14, Behrman had been returned to the Dodgers to rescind the earlier purchase.

7 Rob Edelman, “Hank Behrman,” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

8 Dink Carroll, “Royals Lose Opener to Bears 3-2, in 11 Innings,” Montreal Gazette, April 23, 1948: 16.

9 “Bears Win in 11th from Royals, 3-2,” New York Times, April 23, 1948: 31.

10 Willie Klein, “Plumber Porterfield Shuts Off Rival Runs for 22 Rounds in Row,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1948: 21.

11 Connors was a better actor than a defensive first baseman. He is best known for a five-year role (1958-1963) as Lucas McCain in the popular television series The Rifleman.

12 “1947 World Series Game Six: Al Gionfriddo Robs Joe DiMaggio of Homer,” YouTube.com, October 5, 1947, youtube.com/watch?v=D2aSI0u7F3A.

13 Rory Costello, “Al Gionfriddo,” SABR Baseball Biography Project.

14 Warren Corbett, “Bob Porterfield,” SABR Baseball Biography Project. In the seventh inning of Porterfield’s debut against the Indians, “pinch-hitter Hal Peck smashed a liner off the rookie pitcher’s bare hand, knocking him out of the game. The injury was not serious, but it set the tone for his Yankee career.”

15 Ralph Brown, Buddy Heslet, Bob Keegan, Hank LaManna, Edward Little, Johnny Lucadello, John Maldovan, Joseph Och, Bob Porterfield, Ted Sepkowski, Ken Silvestri, and Odie Strain signed the baseball.

16 Gregory H. Wolf, “Keegan Uses New Motion to Toss No-Hitter,” in Gregory H. Wolf, ed., The Base Ball Palace of the World, Comiskey Park (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2019), 161. Gregory H. Wolf, “August 20, 1957: Bob Keegan Uses New Motion to Toss No-Hitter at Comiskey Park,” SABR Baseball Games Project.

17 Kritzer.

18 Carroll.

Additional Stats

Newark Bears 3

Montreal Royals 2

11 innings

Ruppert Stadium

Newark, NJ

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.