April 24, 1917: Lefty George Mogridge hurls the Yankees’ first no-hitter

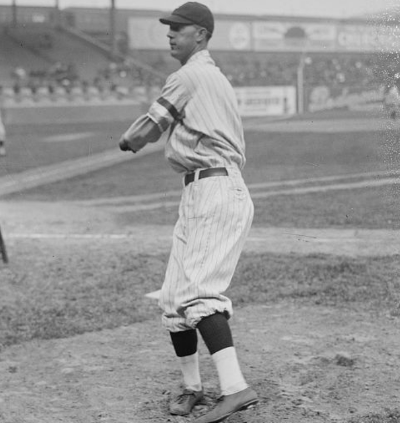

By 1917 the New York American League franchise, first called the Highlanders and then the Yankees, had been around for 15 years. In that time, despite featuring some of the great pitchers of the era like Jack Chesbro, Ray Caldwell, Hippo Vaughn, and Al Orth, no Yankee had twirled a no-hitter. The honor of throwing the first Yankee no-hitter fell to a little regarded tall, lanky left-hander from the sandlots of Rochester, New York, named George Mogridge. In a 15-year major-league career, Mogridge compiled a 132-133 won-lost record pitching mostly for the Yankees and the Washington Senators. His name usually gets mentioned these days only when a Yankee pitcher throws a no-hitter, and a sportswriter checks the Yankees media guide to see who pitched the first one.

By 1917 the New York American League franchise, first called the Highlanders and then the Yankees, had been around for 15 years. In that time, despite featuring some of the great pitchers of the era like Jack Chesbro, Ray Caldwell, Hippo Vaughn, and Al Orth, no Yankee had twirled a no-hitter. The honor of throwing the first Yankee no-hitter fell to a little regarded tall, lanky left-hander from the sandlots of Rochester, New York, named George Mogridge. In a 15-year major-league career, Mogridge compiled a 132-133 won-lost record pitching mostly for the Yankees and the Washington Senators. His name usually gets mentioned these days only when a Yankee pitcher throws a no-hitter, and a sportswriter checks the Yankees media guide to see who pitched the first one.

In 1917, Mogridge was in his second full year with the Yankees. In 1915 he had been plucked off the Des Moines Boosters’ roster by manager Wild Bill Donovan after going 24-11 with a 1.93 ERA and leading the Boosters to the Western League championship. With the Yankees in 1916, he was 6-12 with a 2.31 ERA.

Donovan liked to match Mogridge up against Boston. In 1916 he had gone 2-1 with an excellent 0.77 ERA against the Red Sox, who eventually won the AL pennant and World Series. On April 24, 1917, Mogridge made his second start of the new season, both against the two-time defending champion Red Sox. Ten days earlier, at the Polo Grounds in New York, he had pitched a complete game in defeating the Red Sox and future Hall of Famer (and Yankee) Herb Pennock, 7-2. The only blemishes that day were an RBI double by pinch-hitter Jimmy Walsh and a home run by Tillie Walker.

Mogridge’s mound opponent on this day was left-handed flamethrower Dutch Leonard. Leonard was coming off an 18-12 season and a complete-game victory over the Brooklyn Robins in the World Series. The spring day was a cold one at Fenway Park, which kept the attendance down to just 3,219. The hardy fans were rewarded for their fortitude with a classic.1

The Yankees threatened in the top of the first when third baseman Larry Gardner muffed Hugh High’s hot grounder and Wally Pipp drew a base on balls, but right fielder Harry Hooper made a fine running catch on Fritz Maisel’s drive to shut down any scoring opportunity. In the bottom of the inning, Mogridge retired the Red Sox on three fly balls.

Lee Magee opened the Yankees second with a single and moved up on Roger Peckinpaugh’s sacrifice, but he was stranded there as Les Nunamaker and Mogridge made outs. In the bottom half, Duffy Lewis was safe on shortstop Peckinpaugh’s error and moved up on Walker’s sacrifice. Gardner walked, but was erased when Everett Scott grounded into a force out. With runners on first and third and two out, the Red Sox attempted a double steal, but Scott was run down in the basepaths before Lewis had a chance to score.

Both Mogridge and Leonard had an easy time of it from the third through the fifth, with neither side threatening to score. In the sixth, the Yankees broke the scoreless stalemate with a run. With two out, Angel Aragon, playing third base in place of the ailing Home Run Baker, doubled over the head of Walker in center field. Magee singled to left and when the ball went through Lewis, Aragon scored and Magee moved up to second. Peckinpaugh then singled to center, but Walker charged and made a perfect throw to catcher Hick Cady to nail Magee at the plate. Mogridge set down the Red Sox in the bottom of the inning and the game moved to the late innings with the Yankees up 1-0.

Nunamaker singled for the Yankees to lead off the seventh and Mogridge sacrificed him along, but Frank Gilhooley flied out and Paddy Bauman, batting for High, was retired. The Red Sox tied the game in the seventh without benefit of a hit. Mogridge walked Jack Barry to start the inning and then Peckinpaugh dropped a throw from second baseman Maisel on a potential double-play ball. Lewis sacrificed the runners to second and third. Manager Donovan ordered that the dangerous Walker be intentionally walked, loading the bases. Jimmy Walsh batted for Gardner and he launched a sacrifice fly to right to score Barry with the tying run and advance the other runners. Mogridge escaped further damage by retiring Scott.

Maisel singled to open the eighth and was sacrificed to second by Pipp, but he did not advance beyond third. The Red Sox went down quietly in the bottom of the inning.

In the top of the ninth, Peckinpaugh singled past Mike McNally, who had replaced Gardner at third. Peckinpaugh stole second on the next pitch and advanced to third when catcher Cady’s throw went into center field. Nunamaker bounced to third; McNally held the runner, but threw low to first for an error, allowing Peckinpaugh to score the go-ahead run.

With a 2-1 lead, Mogridge went to the mound in the bottom of the ninth with his no-hitter and the game on the line. He retired the first two batters easily, and with two outs induced Duffy Lewis to hit a groundball to Maisel at second. Maisel fumbled the ball for an error, however, allowing the dangerous Tillie Walker to come up.

As Mogridge later told the New York Tribune’s Grantland Rice, “It was not until two men were out that I got my shock. I had only one man to get and he tapped an easy one for an easy out. An error resulted, and with such a fine chance gone it occurred to me the next man up [Walker] was about due. It generally happens that way, leave an opening, and they nail you. That was the first nervousness I felt. I knew the side should be out and I should be on the way to the clubhouse with my no-hit game sewed up.”2 Despite his nervousness, Mogridge got Walker to ground into a force out to complete the no-hitter.

After the game, Mogridge reflected on his feat: “Now there is a world of rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees, and my first thought was to win the ballgame. I never realized [I had a no-hitter] until [manager] Bill Donovan came out and said, ‘It would be a crime to lose this game for they haven’t gotten a blow off you yet.’ It was not until the last of the ninth that I suddenly realized I’d like to have at least one no-hit game in my kit—and especially a no-hit affair against the world champs.”3

Mogridge got that no-hitter in his “kit.” He pitched for another 10 years in the major leagues. Traded from the Yankees to the Senators in 1921, he became a consistent winner. In 1924 he played a major role for the Senators as they beat the New York Giants four games to three in the World Series. No less a judge of pitching talent than Babe Ruth once lamented the trade that sent Mogridge to Washington, saying, “Not attempting to question [manager] Miller Huggins, I thought we might have kept George Mogridge. I think he is the best left-handed pitcher in the league.”4

Sources

Because there was no play-by-play available for this game, the author deduced the events of the game from contemporary newspaper articles. Articles consulted included the following:

Shannon, Paul H. “No-Hit Game for George Mogridge” Boston Post, April 25, 1917: 13.

Martin, Edward F. “Mogridge Holds Red Sox Hitless,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1917: 11.

“Mogridge Turns in First No-Hit Game by Yankee,” New York Sun, April 25, 1917: 13.

In addition to the newspaper articles and the sources cited in the notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.com.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS191704240.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1917/B04240BOS1917.htm

Notes

1 Paul H. Shannon, “No-Hit Game for George Mogridge,” Boston Post, April 25, 1917: 13.

2 Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” New York Tribune, April 29, 1917: 18.

3 Rice.

4 Babe Ruth, “Ruth Sure Yankees Will Win; To Lead Indians by Five Games,” Washington Times, May 27, 1921: 18.

Additional Stats

New York Yankees 2

Boston Red Sox 1

Fenway Park

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.