August 16-18, 1942: Negro League East stars sweep Comiskey Classic and Cleveland benefit games

As the 10th annual East-West All-Star Game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park approached, the Black press was abuzz with the expectation that Negro League players might finally have the opportunity to break into the major leagues. This hope stemmed from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s July statement in which he had declared, “There is no rule in organized baseball prohibiting [Blacks’] participation and never has been to my knowledge.”1 Soon after, the Chicago Defender reported a rumor that second baseman Sammy Hughes, catcher Roy Campanella, and pitcher Dave “Impo” Barnhill were to have a tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates on August 4. The Defender also claimed, “[S]everal big league scouts will be on hand Sunday, August 16, to take a good look at our boys in action.”2

As the 10th annual East-West All-Star Game at Chicago’s Comiskey Park approached, the Black press was abuzz with the expectation that Negro League players might finally have the opportunity to break into the major leagues. This hope stemmed from Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis’s July statement in which he had declared, “There is no rule in organized baseball prohibiting [Blacks’] participation and never has been to my knowledge.”1 Soon after, the Chicago Defender reported a rumor that second baseman Sammy Hughes, catcher Roy Campanella, and pitcher Dave “Impo” Barnhill were to have a tryout with the Pittsburgh Pirates on August 4. The Defender also claimed, “[S]everal big league scouts will be on hand Sunday, August 16, to take a good look at our boys in action.”2

The Pittsburgh tryouts never came to pass, which revealed the disingenuousness of Landis’s statement as well as the true sentiments of Organized Baseball’s owners. White baseball’s color line had reared its ugly head again, and the Black press made no mention of any scouts attending Comiskey Park in postgame articles either.

Nonetheless, the Chicago game had become the highlight of every Negro League season, and upward of 50,000 fans were expected to attend in 1942.3 What those fans, who came from all over the country, did not know was that the eagerly anticipated game almost did not come to pass. The Pittsburgh Courier later reported that on the eve of the game, “The money question was the bugaboo that sent the western squad into a huddle from which emanated the ultimatum that unless their ante was raised[,] they refused to play the game.”4 The East team was also unhappy, but manager Vic Harris caught wind of his players’ clandestine grievance session and stepped into the proceedings. According to the Courier, “After Vic had belched his little woof[,] the easterners rescinded their plot of revolt, and the westerners agreed to a compromise.”5

There were additional snags on game day. Although a crowd of 48,179 (45,179 paid) filed into Comiskey, that number fell short of the previous year’s record of 50,256.6 Attendance might have been greater had it not been for the fact that “in some mix-up not enough [tickets] were printed. Consequently, over 5,000 fans milled in 35th Street on Shields Avenue and on 34th Street trying vainly to buy their way in.”7 The excess throng resulted in “traffic outside the park [being] so heavy that Satchel Paige was unable to get to the dressing room until the game was well on its way.”8 Paige had been scheduled to start for the West opposite Leon Day for the East, but the traffic delay resulted in both hurlers being saved until the seventh inning.

On top of the chaos outside the ballpark, there was one last issue to be settled inside as “[p]regame matters among the umpires for the game also went awry. Three of the four arbiters came equipped to work behind the plate, each evidently intent on being the head-man of the extravaganza.”9 This problem, too, was solved and it was time to play ball.

Hilton Smith stepped into the host West team’s starting slot in place of Paige while Jonas Gaines took the mound first for the East. Both hurlers put up zeros on the scoreboard in the first two innings before each surrendered a run in the third. The East got to Smith when Dan Wilson of the New York Black Yankees “dropped a Texas leaguer into left center that was good for two bases” and Sam Bankhead followed with an RBI double.10

The West scored its tally in the bottom of the third primarily because of two uncharacteristic errors by the East’s third baseman, Andrew “Pat” Patterson. Smith hit an easy one-out grounder to third, but Patterson’s wild throw to first allowed him to take second; Fred Bankhead (Sam’s brother) ran for Smith. James “Cool Papa” Bell hit a grounder that East shortstop Willie Wells fielded and threw to Patterson to cut down Bankhead at third; however, Patterson dropped the ball, Bankhead hustled back to second, and the West had two men on with one out. Parnell Woods hit a potential double-play grounder to Sam Bankhead at second, but he was unable to throw out Woods at first and Fred Bankhead scored for a 1-1 tie. Gaines escaped further trouble and the affair remained knotted through the fourth.

In the top of the fifth, Wilson drew a leadoff walk from Porter Moss and stole second. After a fly out by Wells, slugger Josh Gibson laced a single through the hole at shortstop that drove in Wilson for the second East run of the day. The West came back in the bottom of the sixth. Woods started things off with a triple and scored three batters later via Joe Greene’s slow-rolling fielder’s-choice grounder to Sam Bankhead.

In the top of the seventh, the player everyone wanted to see – Leroy “Satchel” Paige – finally strode to the mound for the West. Newark’s Len Pearson lofted a fly that fell for a double when right fielder Ted Strong lost the ball in the sun. Wilson, making a case as the game’s unofficial MVP, beat out a bunt for a hit and advanced Pearson to third. Sam Bankhead’s fly ball plated Pearson for a 3-2 East lead. Wells singled and pulled off a double steal with Wilson, after which Paige intentionally walked his old batterymate Gibson. The gamble paid off when Bill Wright grounded into an inning-ending double play.

Southpaw Barney Brown took the mound for the East in the bottom of the seventh but was pulled when he allowed two-out singles to Paige and Bell. Day entered the game and quelled the nascent West uprising by retiring pinch-hitter Marlin Carter, who was batting for Woods. After a scoreless eighth inning, the East’s man of the hour again found himself in the middle of the action.

Wilson led off the ninth a slow roller in Buck O’Neil’s direction, and the Monarchs first sacker overthrew Paige, who was covering the base, which allowed Wilson to advance to second. Sam Bankhead bunted and was safe at first when second baseman Tommy Sampson, the next player to cover first, dropped O’Neil’s throw. For the second time, Paige issued a free pass to Gibson to load the bases. This time the strategy backfired as Wright singled to drive in Wilson and Bankhead with the final two runs of the game. In the bottom of the frame, Day struck out the side to seal the East’s 5-2 victory.

After the Comiskey Park game, the same two All-Star squads traveled to Cleveland to stage a second game for the Eastern crowd at Municipal Stadium. It was only the second time in the 10-year history of the East-West Game that an Eastern tilt took place, the first having occurred in 1939. This time around, the second game was not played to fill owners’ and promoters’ pockets but to benefit the Army and Navy Emergency Relief Fund.

The August 18 East-West Game marked the first of its kind in Cleveland – the 1939 Eastern game had been played at Yankee Stadium – and the Chicago Defender averred, “The city is all agog over this great game and no efforts are being spared to make this attraction one of the greatest in the history of Cleveland.”11 The Defender’s assertion was not entirely true and a debate ensued over the lighting to be used for the night game that delayed play by 25 minutes. Under the terms of the contract for the event, the game was to be played under the lights used for football; however, the crowd began to clamor for the floodlights used during Indians games at the ballpark. The players left the field until the issue was resolved when “Dick Kroesen, chairman of the Army and Navy Relief Fund of Cuyahoga County, arranged to have the brighter lights turned on and guaranteed to pay the added expense for their usage.”12

Once the added lighting was on, the players and the 10,794 spectators, who constituted the “largest [crowd] ever to see a Negro game in the stadium,” were satisfied.13 After Cleveland’s mayor, Frank J. Lausche, threw the ceremonial first pitch to the Negro American League president, Dr. J.B. Martin, the game began at last.

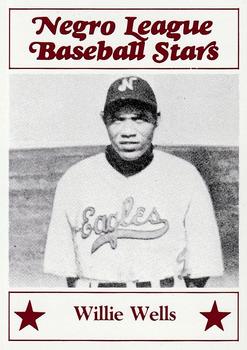

Although the event was held for a good cause, the press treated the game itself as an afterthought to the annual Comiskey Park classic and barely covered the on-field action.14 Cincinnati Buckeyes pitcher Eugene Bremer started for the West – Paige was out with a sore arm – and was tagged for five runs in the top of the third inning. The West recouped two runs in the bottom of the frame, but those marked their only scores in a 9-2 defeat that gave the East squad a sweep of the two games. Newark’s Willie Wells led the East’s hitters as he went 3-for-4 at the plate with three RBIs and one run scored. While the media neglected to cover the game in any detail, it did note that the crowd “contributed $9,499.04, the largest amount raised by an individual Negro organization” for the Relief Fund.15

Taken together, the two East-West games, in the opinion of one Atlanta Daily World columnist, also had helped to accomplish more than to highlight the best players in the Negro Leagues and to raise money for the Army and Navy Relief Fund. Columnist Lucius “Melancholy” Jones wrote:

“Whether or not Negro players get their rightful and deserved chance at performing in major league baseball next season … I note four significant gains, all of which may be attributed to the effort of those leading the Negro baseball integration fight. They are as follows:

- An improved attitude generally toward Negro professional baseball as an institution;

- Increased white attendance at Negro games;

- Increased pride on the part of Negroes generally in their own stars; and

- The fight has become a fine vehicle for integrating the efforts of Negroes in all other lines of endeavor.”16

The annual East-West All-Star Game continued to provide a venue that featured the best players in the Negro Leagues. It took another five years, but Organized Baseball finally relented and former Kansas City Monarch Jackie Robinson made his debut as the first twentieth-century Black player in the major leagues on April 15, 1947, when he started at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Sources

The descriptions of the scoring plays from the August 16 game at Comiskey Park were adapted from the following article:

Day, John C. “Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, August 22, 1942: 19.

Notes

1 David Pietrusza, Judge and Jury: The Life and Times of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, 1998), 417.

2 “Big League Scouts to Watch East-West Game: Campanella Leads Gibson for Backstop/Paige and Barnhill to Pitch in Classic on August 16,” Chicago Defender, August 1, 1942: 20.

3 “Expect 50,000 at East-West Game: East-West Classic Will Draw 50,000/Pick Paige and Day to Start Game Sunday at Comiskey Park,” Chicago Defender, August 15, 1942: 1.

4 Randy Dixon, “The Sports Bugle,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 5, 1942: 16.

5 Dixon.

6 Dan Burley, “East Wins First Game in Four Years; Brains, Wilson Did It,” New York Amsterdam News, August 22, 1942: 1. The Amsterdam News’ headline was in error as the East had won, 11-0, in 1940 and by an 8-3 score in 1941. There was also a minor discrepancy over the exact attendance as the Amsterdam News reported a total of 48,179 while the Chicago Defender gave a total attendance of 48,400; both papers listed the paid attendance as 45,179. See also: Frank A. Young, “48,000 See East All-Stars Beat Paige and West,” Chicago Defender, August 22, 1942: 19.

7 Burley.

8 “48,000 See Paige Lose: Negro All-Star Nine of East Is Victor over West by 5-2,” New York Times, August 17, 1942: 21.

9 Dixon.

10 John C. Day, “Play by Play,” Chicago Defender, August 22, 1942: 19.

11 G.L. Porter, “Same Teams Play Benefit Game in Cleveland, Aug. 18,” Chicago Defender, August 15, 1942: 19.

12 “East’s All-Stars Whip West, 9-2/Controversy over Lights Delays Negro Benefit Game,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 19, 1942: 18.

13 “East’s All-Stars Whip West, 9-2.”

14 In addition to the 1939 and 1942 seasons, two East-West games were played in 1946, 1947, and 1948. Attendance at the Eastern games normally paled in comparison to the turnout for the annual Western game at Comiskey Park. Only once, in 1947 at New York’s Polo Grounds, did Eastern attendance come anywhere close to the crowd at Comiskey; that year 38,402 spectators attended the Eastern game, which was still considerably fewer than the 48,112 who attended the Chicago game.

15 “East Bumps West Again: Army and Navy Relief Funds Get $9,499,” Chicago Defender, August 29, 1942: 19.

16 Lucius (Melancholy) Jones, “Sports Slants,” Atlanta Daily World, August 16, 1942: 8.

Additional Stats

East All-Stars 5

West All-Stars 2

Comiskey Park

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

East All-Stars 9

West All-Stars 2

Municipal Stadium

Cleveland, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.