August 26, 1889: Extra baseball, a free fight, and a protest in Philadelphia

The courses of the Philadelphia Phillies and Boston Beaneaters had diverged by the time Boston arrived in Philadelphia for a three-game series on Monday, August 26, 1889. A week before, Boston had stretched its lead in the National League pennant chase with three victories over the second-place New York Giants, while the Phillies continued to fall off the pace, losing four of five to the Giants. With September fast approaching, the Beaneaters arrived in Philadelphia with just a 3½-game lead in the NL standings.

The courses of the Philadelphia Phillies and Boston Beaneaters had diverged by the time Boston arrived in Philadelphia for a three-game series on Monday, August 26, 1889. A week before, Boston had stretched its lead in the National League pennant chase with three victories over the second-place New York Giants, while the Phillies continued to fall off the pace, losing four of five to the Giants. With September fast approaching, the Beaneaters arrived in Philadelphia with just a 3½-game lead in the NL standings.

A crowd of 6,452 filed into Philadelphia Ball Park to watch the Phillies try to regain their form against Boston.1 Among those in attendance was A.G. Spalding, sporting goods magnate and owner of the Chicago club, who was in town to finalize the acquisition of the A.J. Reach Co.2 The game began at 4 P.M. on a cloudy day with slight winds and a temperature of 68 degrees.3 Boston owner Arthur Soden, breaking with tradition, requested that two umpires be assigned for the series.4 Ben Sanders and William “Pop” Schriver composed the Phillies battery while John Clarkson and Charlie Bennett formed the Boston combination.

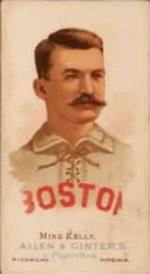

The Phillies, with venerable Harry Wright in his sixth season at the helm, batted first but went down without much of a threat. In the bottom of the first, Boston’s Hardy Richardson reached first on an errant throw by shortstop Bill Hallman and took second on Mike “King” Kelly’s groundout. After Billy Nash walked, Dan Brouthers doubled to center field, scoring Richardson and Nash. Boston led, 2-0.

The score remained the same through three innings, but Philadelphia rallied in the top of the fourth. Al Myers led off with a walk and advanced to second on Sam Thompson’s single to center field. One out later, Schriver hit an apparent double-play ball to Joe Quinn at second base, but shortstop Charles “Pop” Smith let the throw to second go through his legs, allowing Myers to score Philadelphia’s first run of the game.

The Phillies were in position to tie the game after Thompson took third on the play, but Bennett threw out Schriver attempting to steal second, and Jim Fogarty flied out to Dick Johnston in center, stranding Thompson.

Boston answered in its half of the inning, Quinn led off with a single and stole second. With two outs, he took third on a passed ball, and scored on a wild pitch. Boston led 3-1 after four innings.

Neither team scored in the fifth, sixth, or seventh, but Philadelphia stirred again in the eighth. Ed Delahanty, the Phillies’ 21-year-old budding star, smashed a single to left field. Hallman struck out, but Clarkson walked Myers. Thompson struck out on three pitches.

With two out and two on, Mulvey lined a single to center, scoring Delahanty and making the score 3-2. Mulvey attempted to get into scoring position himself, but Johnston threw to Nash, who relayed to Smith for the tag on Mulvey at second, ending the inning. Boston had a baserunner in the bottom of the inning but did not score.

Down to their final three outs, the Phillies took the lead in the top of the ninth. Shriver led off with a single. At this point, the Boston Globe reported that the Phillies began mocking two high-profile Boston supporters. “The Quakers stood up and howled back ‘hi! Hi! Hi!’ at Arthur ‘Hi! Hi!’ Dixwell and John Haggerty, who occupied a private box.”5 Haggerty, Boston’s groundskeeper, was being rewarded for his service to the club with a vacation trip with the team courtesy of Boston superfan Arthur Dixwell.

Brouthers turned Fogarty’s grounder to first into a force at second, but Fogarty stole second and scored the tying run on Farrar’s double to the outfield wall. Sanders then helped his own cause by hitting a ball to left that scored Farrar to put Philadelphia ahead for the first time in the game. The Boston Globe described the mood: “Harry Wright looked around to see how the crowd enjoyed his pets, and … A.G. Spalding …who occupied a box alongside the scribes, said it reminded him of the old ’75 days in this city, when he was a member of the team.”6

The Phillies were now themselves three outs from a win, but the Beaneaters’ Quinn hit a hot shot past shortstop Hallman and went to third on Smith’s single to right field. After Bennett struck out, Smith stole second. Quinn scored the tying run on Clarkson’s fly out to Fogarty in center. The suspense in the crowd began to build.7 Kelly stranded Smith at third when he grounded out sharply to Hallman. The game was tied 4-4 at the end of nine innings.

Despite opportunities, neither team scored in the 10th or 11th inning. The Phillies went down in short order in the top of the 12th.

In the bottom of the inning, with one out, King Kelly hit a bounding ball to Hallman, who threw wide of first, allowing Kelly to take second. Nash then fouled out to Schriver at the plate, and Sanders intentionally walked the dangerous Brouthers, who went on to earn his third career NL batting title in 1889 with a .373 average.

Johnston smashed a hard liner to center; Fogarty sprinted in and attempted to scoop the ball, but it bounded over his head and rolled to the wall. Kelly hustled around third and crossed home plate, apparently ending the game.

According to various newspaper reports, Johnston saw the ball bounce past Fogarty and saw Kelly rounding third, but he did not touch first base. Once Kelly scored, the crowd hopped onto the field to make their exit.

The details of what followed vary by newspaper, but amid the growing commotion, the ball was thrown into the infield, where Bennett received it and gave it to Kelly, in accordance with the custom that the winning side kept the game ball.

Farrar then chased after Kelly and demanded the ball, but Kelly refused to give it to him. The Times carried Kelly’s explanation: “Farrar … asked me for the ball, but I refused to give it to him, as I thought he wanted to substitute an old ball for it.”8 From here, the confrontation escalated.

Farrar proceeded to grab for the ball. Sanders and Delahanty joined him. The crowd, seeing the commotion, began to congregate around the players. Police officers took notice, too. “Now the crowd was upon the field, and in an instant 200 … [people] … were surging around Kelly, Farrar and the policeman. In another second the mob had swelled to 2,000 and Mike Kelly was bobbing about like a cork on the ocean’s waves.”9

Quinn, bat in hand, and other Boston players rushed to Kelly’s aid. The crowd began yelling at and threatening Kelly and the Boston players. “‘Johnston has not touched his base,’ went through the crowd like wildfire, and the crowd [was] worked up to a white heat over the result. … [E]very one seemed to want to get their hands on Kelly.”10

A fan punched Quinn while another hit Johnston on the jaw. “Then the fighting became general.”11 As Kelly and his teammates tried to push their way through the crowd toward the clubhouse, fans still in the grandstand threw their seat cushions at Kelly. The police pushed their way through the crowd using their clubs. Finally, Kelly and his teammates made their way into the clubhouse while Boston utilityman Charlie Ganzel stood outside the door with his bat.

At some point, Delahanty obtained the ball, ran to first base, and claimed to have made the third out of the inning. Neither umpire, however, was on the field to make a call.

“McQuaide [sic] and Curry had dived under the pavilion at the opening of hostilities and it took ten minutes to hunt them up.”12 McQuade was in charge of the base decisions and during the play focused on Kelly to ensure that he touched third base while Curry was watching the play unfold in the outfield. Neither saw whether Johnston touched first base.

Some fans remained outside of the ballpark waiting for the Boston contingent to leave the grounds. They shouted and threw bricks at the Boston players and journalists as the Bostonians left via the omnibus. Wright waited with Kelly in the clubhouse for a half-hour before he was able to leave.

Phillies owner John Rogers filed a protest with the National League, claiming that Johnston did not touch first base and that the game should be declared a tie.13 Despite the protest and evidence provided by Rogers, the League did not rule in the Phillies’ favor, and Boston’s victory stood.14

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the City Item, and the Boston Post.

Notes

1 “Kelly Stole the Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1889: 6.

2 “Around the Hotels,” Philadelphia Times, August 26, 1889: 2; “The Deal Completed,” Philadelphia Times, August 31, 1889: 2.

3 “The Weather,” Philadelphia Record, August 27, 1889: 1; T.H. Murnane, “Roasted by Umpires,” Boston Globe, August 26, 1889: 5.

4 “Roasted by Umpires.”

5 “Roasted by Umpires.”

6 “Roasted by Umpires.”

7 “Roasted by Umpires.” “Kelly Stole the Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1889: 6.

8 “Kelly’s Explanation,” Philadelphia Times, August 27, 1889” 1.

9 “A Free Fight on the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1889: 6.

10 “Got a Smash in the Neck,” Boston Globe, August 27, 1889: 5.

11 “A Free Fight on the Diamond.”

12 “Kelly Gives Up the Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 27, 1889: 6.

13 The full text of Rogers’ protest can be found in “The Phillies’ Protest,” Sporting Life, September 4, 1889: 1.

14 Sporting Life, September 25, 1889: 4.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters 5

Philadelphia Phillies 4

Philadelphia Ball Park

Philadelphia, PA

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.