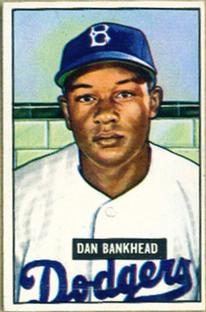

August 26, 1947: Pitcher Dan Bankhead becomes an integration pioneer, homers in Dodgers debut

Until the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Dan Bankhead was on record as the first African American to pitch in the majors. After the Brooklyn Dodgers acquired him from the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League, the 27-year-old made his debut in the National League on August 26, 1947.

Until the Negro Leagues were officially recognized as major leagues in December 2020, Dan Bankhead was on record as the first African American to pitch in the majors. After the Brooklyn Dodgers acquired him from the Memphis Red Sox of the Negro American League, the 27-year-old made his debut in the National League on August 26, 1947.

On April 15 that year, Bankhead’s teammate on the Dodgers, Jackie Robinson, had broken the color barrier that had been in place at the top level since 1884. Until then, Fleet Walker and his brother Weldy had been the last African Americans in the National or American League for nearly 63 years. (Along the way, however, various Latin Americans of partial African descent “blurred the line.”1)

Robinson was followed on July 5 by the AL’s first integration pioneer, Larry Doby. Shortly after Doby, Hank Thompson (July 17) and Willard Brown (July 19) made their AL debuts with the St. Louis Browns. Then came Bankhead, whom the Dodgers obtained from Memphis after securing a six-day option on his services on August 23.2 The option was exercised and the newly signed pitcher caught an overnight flight to Brooklyn.3 He was introduced to the press on August 25.4

Brooklyn’s president, part-owner, and general manager, Branch Rickey, would have preferred to test his new pitcher in the minors first. However, he needed a live arm more. Brooklyn beat writer Harold C. Burr said, “Rickey thinks the Dodger pitching situation is desperate.”5 Burr also detailed, “The injury to Harry Taylor’s pitching elbow has thrown the staff into confusion.”6 Furthermore, the mound corps had shouldered a heavy workload, with doubleheaders on August 17 and 18 followed by 12-inning games on the 20th and 22nd. Ironically, the club unloaded starter Kirby Higbe in an early May trade with Pittsburgh because he refused to play with Jackie Robinson.

Even so, as play began on Tuesday afternoon, August 26, Brooklyn had won five straight and held first place in the NL, with a sizable lead of six games over the St. Louis Cardinals. The visiting Pittsburgh Pirates were in seventh place, 24½ games out.

However, the Pirates’ starting pitcher, Fritz Ostermueller, took the mound with a much more impressive record of 11-7 and a 3.59 ERA. As Fred Lieb wrote of the 1947 Pittsburgh squad, “Whenever old Fritz Ostermueller … was on the hill, the other side knew they were in a ball game.”7 The 39-year-old lefty was opposed by Hal Gregg, whose marks of 3-4 and 6.38 were uninspiring.

What’s more, the New York press recognized that Pittsburgh’s offense was potent.8 Indeed, the Pirates lit up Gregg for four runs in the first inning. The big blow was Wally Westlake’s three-run homer.

In the top of the second, Gregg started by allowing a single to Ostermueller – a good-hitting pitcher, with a .234 lifetime batting average across 15 big-league seasons. He then walked shortstop Billy Cox, the noted glove man who became Brooklyn’s primary third baseman from 1948 through 1954.

Dodgers manager Burt Shotton had seen enough of Gregg. He summoned Bankhead, whose appearance had been anticipated. One news story estimated that Black fans made up roughly a third of the day’s crowd of 24,069 at Ebbets Field.9

Bankhead was very nervous. After the game, he told the respected Black sportswriter Sam Lacy, “I think I’ll be okay as soon as this newness wears off. Today it seemed like I was wearing a new glove, new shoes, new hat, everything seemed tight.”10 The first batter he faced, Jim Russell, doubled to score Ostermueller. After Elbie Fletcher’s fly ball brought in Cox, Ralph Kiner singled and Frankie Gustine doubled; already the Bucs were up 8-0. Bankhead escaped the inning without further damage.

Ostermueller got two outs to start the bottom of the second but then walked shortstop Stan Rojek. That brought up Bankhead, who had reportedly been hitting .385 for Memphis.11 He connected on a 1-and-2 pitch – after fouling off four – for a two-run homer.12 As the New York Daily News described it, “Dan stepped into one of Ostermueller’s serves and sailed it well into the lower deck. And that, 8-2, was as much as the Brooks were ever in the game.”13 The liner traveled about 375 feet and landed in the fifth row of the left-field seats.14 This made Bankhead the first pitcher in the NL or AL to homer in his first at-bat since Bill LeFebvre of the Boston Red Sox on June 10, 1938. The next to accomplish the feat would be Hoyt Wilhelm of the New York Giants on April 23, 1952.15

Bankhead worked a one-two-three third inning and retired the first two men he faced in the fourth. However, he then got into hot water as Kiner and Gustine singled, and he suffered a lapse in control. “His first pitch to Pirates outfielder Wally Westlake came inside too far. As Westlake remembered it 60 years later, the pitch bore in hard, as Bankhead’s high-octane fastballs tended to do, and struck Westlake around the left elbow.

“I couldn’t get away from it,” Westlake said. “He just about took my left arm off.’”16

The undercurrent was whether the drilling might provoke a race-based fight. Fortunately, Westlake simply took his base. The bases were loaded, but Bankhead got out of the jam by getting Jimmy Bloodworth to ground to short.

Brooklyn offered a mild threat in the bottom of the fourth with two one-out singles, but Ostermueller got away without a run by inducing a 6-4-3 double play.

The Pirates started the fifth inning with a triple by Clyde Kluttz and another single by Ostermueller, hit sharply to right.17 A homer by Cox followed. Bankhead struck out Russell but then allowed a walk and two more singles. That was all for Bankhead, who was replaced by Rex Barney. Barney promptly gave up a double to Westlake, which scored two runs and closed the books for Bankhead on the afternoon. He had allowed eight runs (all earned) on 10 hits in his 3⅓ innings of work that day. In one of his well-honed turns of phrase, sportswriter Red Smith wrote, “(T)he Pirates launched Bankhead by breaking a Louisville Slugger over his prow.”18

After doubling, Westlake scored on an error by Robinson to make the score 15-2. Barney went the rest of the way for Brooklyn, allowing just one more run, a homer by Culley Rikard to lead off the ninth.

Ostermueller then set the Dodgers down in order, finishing his complete game. The only other run he had allowed was a fifth-inning homer by Eddie Miksis. His 12th win was his last of the season but he still wound up leading the Pittsburgh staff for the year.

In addition to nerves, Bankhead also said that he’d been overworked with Memphis during the two weeks before joining Brooklyn, starting three times a week and coming out of the bullpen, too. The 6-foot-1 righty noted that his weight was down to 170 pounds from his normal 185-190.19

Burt Shotton mixed praise (“speed, a good curve, and control”) and criticism (“the boys were calling all his pitches”) in his postgame remarks about Bankhead. He said he “wanted another look before I form an opinion one way or another.”20

The Dodgers won the 1947 NL pennant with a record of 94-60-1. Of those 60 defeats, only one was worse: a 19-2 trouncing on July 3 by Brooklyn’s archrival, the Giants. That game also took place at Ebbets; the starter and loser was Hal Gregg. That time, too, Gregg was knocked out of the box in the second inning.

Bankhead pitched in just three more games over the remainder of the 1947 regular season, though Shotton used him twice as a pinch-hitter. Bankhead appeared once in the 1947 World Series; as another sign of his all-around ability, he came in as a pinch-runner in Game Six.

Bankhead spent all of 1948 and 1949 in the minors. His only full season in the NL was 1950. (He never appeared in the AL.) His last major-league game came with the Dodgers on July 18, 1951. The shoulder soreness that had bothered him the previous year really ailed him in 1951.

Yet Bankhead knocked around the US minors and various international circuits – in Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Canada, and especially Mexico – well into his 40s. His last playing action came at age 46 in 1966. He remained a respectable hitter who often played in the field in addition to pitching. Though his 1947 home run was the only one he hit in either the Negro Leagues or the National League, Bankhead hit at least two dozen more in his extended career.

Dan Bankhead died of lung cancer on May 2, 1976 – a day short of his 56th birthday. The former US Marine had been in and out of the Veterans Administration hospital in Houston, Texas. Though press coverage of him was scanty while he was alive, Bankhead’s role as an integration pioneer in baseball has subsequently been recognized.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BRO/BRO194708260.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1947/B08260BRO1947.htm

Photo credit: Dan Bankhead, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 For further discussion, see Adrian Burgos Jr., Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). See also Stephen R. Kenney, “Blurring the Color Line: How Cuban Baseball Players Led to the Racial Integration of Major League Baseball,” The National Pastime: Baseball in the Sunshine State (Society for American Baseball Research, 2016, https://sabr.org/journal/article/blurring-the-color-line-how-cuban-baseball-players-led-to-the-racial-integration-of-major-league-baseball/).

2 “Bums Get Option on Negro Pitcher,” Pittsburgh Press, August 24, 1947: 24.

3 “Dodgers Sign Dan Bankhead, Memphis Negro,” Winona (Minnesota) Republican-Herald, August 25, 1947: 14.

4 “Dan Bankhead Ready to Toil for Brooklyn,” Quad-City (Iowa/Illinois) Times, August 26, 1947: 13.

5 Harold C. Burr, “Slam-Bang Dodger Bow for Robinson’s Roomie, New Pitcher Bankhead,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1947: 7.

6 Harold C. Burr, “Dodgers Don’t Know Own Strength Until They Call to Bench,” The Sporting News, September 3, 1947: 7.

7 Frederick G. Lieb, The Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 293.

8 Burr, “Slam-Bang Dodger Bow for Robinson’s Roomie, New Pitcher Bankhead.” Dick Young, “Flock Bows, 16-3; Bankhead HRs,” New York Daily News, August 27, 1947.

9 “Bucs Win; Bankhead Homers,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 27, 1947: 24.

10 Sam Lacy, “Bankhead Knocked Out in First Dodger Game,” Richmond Afro-American, August 30, 1947: 14.

11 “Dodgers Sign Dan Bankhead, Memphis Negro.”

12 Harold C. Burr, “Pirate Massacre Ends Flock Run but Fails to Cut 6-Game Margin,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 27, 1947: 17.

13 Young, “Flock Bows, 16-3; Bankhead HRs.”

14 “Bucs Win; Bankhead Homers.”

15 The list is surprisingly long. See “Pitchers First At-Bat Homers,” San Diego Union-Tribune, August 19, 2015 (https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-pitchers-first-at-bat-homers-2015aug19-story.html).

16 Justice B. Hill, “Bankhead a Baseball Pioneer,” www.mlb.com, August 24, 2007.

17 Young, “Flock Bows, 16-3; Bankhead HRs.”

18 Red Smith, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald-Tribune; date uncertain. Reprinted in Baltimore Afro-American, September 6, 1947: 13.

19 Burr, “Slam-Bang Dodger Bow for Robinson’s Roomie, New Pitcher Bankhead.”

20 Joe Reichler (Associated Press), “Negro Hurler to Get New Chance,” August 27, 1947.

Additional Stats

Pittsburgh Pirates 16

Brooklyn Dodgers 3

Ebbets Field

Brooklyn, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.