August 3, 1969: Fan favorite Chico Fernandez survives near-fatal beaning in minors

Ray Chapman, Tony Conigliaro, Dickie Thon, Adam Greenberg: We recognize the names of big leaguers whose careers and lives were changed forever when they were hit by wayward pitches. Of course, the same thing can happen at any level of baseball, and players in the minors have had the same terrifying experience outside the big-league spotlight. One such beaning on a mild summer Sunday in August 1969 in Rochester, New York, left thousands of fans in shocked silence and a former major leaguer fighting for his life.

Ray Chapman, Tony Conigliaro, Dickie Thon, Adam Greenberg: We recognize the names of big leaguers whose careers and lives were changed forever when they were hit by wayward pitches. Of course, the same thing can happen at any level of baseball, and players in the minors have had the same terrifying experience outside the big-league spotlight. One such beaning on a mild summer Sunday in August 1969 in Rochester, New York, left thousands of fans in shocked silence and a former major leaguer fighting for his life.

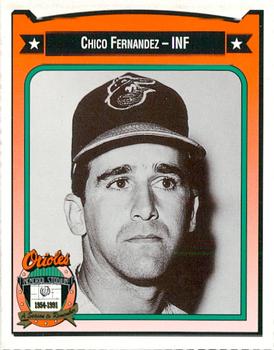

The 1969 season was the 12th in professional baseball for infielder Lorenzo “Chico” Fernandez,1 and his only big-league credentials were 24 games with the Baltimore Orioles the previous year. While he hadn’t found stardom, his smile and outgoing personality — plus his talent, especially in the field — had won him many friends along the way. Ten years after his stint in Montgomery, Alabama, the local sports editor wrote: “If any one player has ever captured the total affection of Montgomery baseball people, it has to be Chico Fernandez, who played shortstop for the 1959 Alabama-Florida League pennant winners.”2 And Hank Bauer, his manager with the Orioles, recalled: “He was good with the glove, not much of a hitter. But a great kind (of person).”3

Fernandez, a father of four, signed on with the Orioles’ Triple-A club in Rochester as a player-coach — emphasis on coach. For much of the ’69 season he worked in support of Red Wings manager Cal Ripken Sr. and didn’t play at all. But when infielder Arturo Miranda suffered a hand injury late in July, Fernandez was activated.4 On the afternoon of Sunday, August 3, Ripken wrote him into the starting lineup at second base against the Mets’ top farm team, the Tidewater Tides. It was Fernandez’s fourth appearance of the season. Both teams were involved in an exciting International League pennant race: Toledo and Louisville were tied for first; Tidewater was in third with a 56-50 record, 2½ games back; and Rochester was 4 games back in fourth place at 54-51.5

Ripken’s lineup mixed career minor-leaguers like right-handed starting pitcher Mike Herson (3-10, 3.87 in 18 starts that season) with better-known names like third baseman Mike Ferraro, left fielder Terry Crowley, center fielder Fred Valentine, and catcher John Sullivan. Tidewater manager Clyde McCullough’s lineup included catcher Duffy Dyer, first baseman Mike Jorgensen, left fielder Jim Gosger, center fielder Amos Otis, and original Met Choo Choo Coleman as designated hitter.6 McCullough’s starting pitcher was righty Larry Bearnarth, who had appeared in 171 games for the Mets between 1963 and 1966 and was still trying to work his way back.

Through the first three innings at Rochester’s old Silver Stadium, the home team held the upper hand. In the second, Wings catcher Sullivan hit a single to drive in shortstop Mickey McGuire, who had taken second base when an attempted double-play relay went into the dugout. In the third, Ferraro hit a solo homer. A walk to Crowley, a double by Valentine, and a groundout by McGuire followed to make it 3-0, Rochester.7

Things came apart for the Wings in the top of the fourth. Tidewater began by tying the game with a single by Jorgensen, a walk to Gosger, and singles by right fielder Roy Foster, Dyer, and Otis — all with none out. The Tides then added six more runs off Herson and relievers John Hofferd and Carroll Moulden to make it 9-3. The local newspaper’s game story does not specify how the remaining runs scored, but the fact that the Tides more than batted around suggests it was a single-here, walk-there type of rally, rather than one or two big blows.8 The Tides added still another run in the fifth to claim a 10-3 lead.

Rochester clawed back two runs in the bottom of the sixth. But that rally would pale in light of what happened when Fernandez — hitless in one at-bat — came to the plate that inning. Fernandez was a conspicuous early adopter of a batting helmet with a protective earflap. But he couldn’t find his helmet before his sixth-inning at-bat, so he borrowed one without an earflap.9 This detail became relevant when Bearnarth loosed a side-arm fastball on an 0-and-2 count that rose higher and tighter than expected.10

Two weeks after the incident, a still-rattled Bearnarth vowed to a reporter that he’d “never thrown at a man in my life.”11 Wings manager Ripken also absolved him of blame, describing the errant fastball as “one of those pitches that sometimes gets away” and noting that Bearnarth had no reason to intentionally pitch high and tight with a big lead.12

Pitched balls, however, do not require ill intent to cause serious damage; and this one hit Fernandez in the head, stunning the crowd of 2,825 fans who watched in silence as Fernandez writhed on the ground, bleeding from one ear. Fernandez was taken to Rochester General Hospital, where doctors found a 2½-inch crack in his skull and fragments of bone pressing against his brain. They later said the pressure on Fernandez’s brain would have killed him without the three hours of surgery they performed later that night.13

Eventually, the game resumed in perfunctory fashion. Bearnarth left the game to visit the hospital, and fellow big-league vet Bill Connors finished up on the mound for Tidewater.14 Both teams added a final run in the ninth inning — Rochester’s on a home run by Valentine, who had three hits that day.15 The game wrapped up in 2 hours and 37 minutes at 11-6, with Bearnarth getting the win and Herson the loss.16

Cal Ripken Sr.’s 8-year-old son, Cal Jr., who often accompanied his father to the ballpark, was at Silver Stadium that day. In 1980, as an up-and-coming third baseman with the Double-A Charlotte O’s, Cal Jr. remembered the event vividly: “Chico Fernandez was a player-coach then, and that night he didn’t have a helmet with an ear flap. He got hit right in the side of the head and they had to carry him off. Now there’s a metal plate in his head, and they had to teach him Spanish all over again.”17

Cal Jr.’s summary, while accurate, didn’t do full justice to the situation. Fernandez suffered temporary but significant impairments to his speech, vision, memory, and ability to walk. After an initial hospital stay of 17 days, Fernandez continued with months of speech and physical therapy, and had a protective plate inserted in his head during follow-up brain surgery in January 1970. “My life was in bad shape. … I almost didn’t make it,” he remembered a few years later. “Then I couldn’t read, couldn’t write. I had to learn all over again like a baby. They’d put big letters of the alphabet on the board and I had to learn what they meant again.”18

The Rochester community and the Orioles organization rallied around Fernandez. The Red Wings held a silent prayer for him before the next day’s game, and hosted a day in his honor at the ballpark on September 1.19 The Wings presented Fernandez with “a sizable check” to help cover his housing and medical expenses.20 Perhaps most importantly, the Orioles kept him in the game he loved: They brought a mostly recovered Fernandez back as a coach with the Red Wings in 1970, then offered him other positions in the organization for several years. Fernandez then moved to the Dodgers organization, where he served for more than 20 years as a roving minor-league infield instructor.21

Bearnarth, who inquired regularly about Fernandez as he recovered, built a lengthy baseball career of his own. He briefly returned to the major leagues with the Brewers in 1971, then became a pitching coach, minor-league manager, and scout in the Expos, Rockies, and Tigers organizations.22 Bearnarth and Fernandez crossed paths several times before Bearnarth’s death in December 1999. The meetings were friendly, as Fernandez held no grudge: “No way was he trying to hit me with that pitch. It was my fault, not his. I crowded the plate. I was looking for a ball outside. I didn’t pick it up. It could have been much worse.”23

Thirty years after the beaning, Fernandez reported no lingering health effects except for slightly impaired vision in his left eye. But even after a lifetime in baseball, he said he still cringed when he saw batters get hit by pitches: “I hate to see it. I know what damage it can do.”24

Sources

In addition to the specific sources cited in the Notes, I used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for general player, team, and season data.

Notes

1 Lorenzo Fernandez is sometimes confused with fellow Cuban Humberto “Chico” Fernandez, a shortstop with four big-league teams between 1956 and 1963 and a teammate of Larry Bearnarth on the ’63 Mets. All mentions of Chico Fernandez in this story refer to Lorenzo.

2 Ray Holliman, “It Was ‘Our Chico,’” Alabama Journal (Montgomery, Alabama), August 6, 1969: 14.

3 Craig Stolze, “Chico Packs Memories,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, April 28, 1971: D1.

4 Craig Stolze, “Prayers for Chico,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 5, 1969: 1A.

5 International League standings as printed in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 3, 1969.

6 The 1969 season was the International League’s first using the DH. John Cronin, “The Historical Evolution of the Designated Hitter Rule,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2016.

7 Larry Bump, “Tides Swamp Wings,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 4, 1969: D1.

8 Bump.

9 Several stories, including Scott Pitoniak, “The Day Silver Went Silent,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 1, 1999: D1.

10 In “The Day Silver Went Silent,” a 30-year retrospective story, Bearnarth recalled the pitch as a side-arm curve, but stories from 1969 consistently describe it as a side-arm fastball.

11 Paul Pinckney, “I’ve Never Thrown at a Man,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 17, 1969: D1.

12 Stolze, “Prayers for Chico.”

13 Pitoniak.

14 In “The Day Silver Went Silent,” Bearnarth recalled staying in the game and getting knocked around by the Wings because his heart had gone out of pitching. But news accounts from 1969 consistently have him leaving the game for the hospital immediately after the beaning. In a 1973 interview with the Miami News, Fernandez said he’d been told Bearnarth reached the hospital before he did.

15 Bump.

16 As per box and line scores published in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle on August 4, 1969, and The Sporting News on August 16, 1969.

17 Stan Olson, “The Fastball: It Injects Fear, But Players Must Beat It to Survive,” Charlotte (North Carolina) News, July 14, 1980: 2B.

18 Charlie Nobles, “Beanball Nearly Killed M-Oriole Aide,” Miami News, January 22, 1973: C1.

19 Pitoniak. In 1999 Fernandez admitted he had scant memory of the day in his honor, which was held a little more than a week after his release from the hospital.

20 Paul Pinckney, “The Good Side,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 24, 1969: D1.

21 “Baseball Notes: Deal for Marlins Seems to Be Dead in the Water,” Los Angeles Times, November 5, 1998: D7.

22 David E. Skelton, “Larry Bearnarth,” SABR Biography Project.

23 Pitoniak.

24 Pitoniak.

Additional Stats

Tidewater Tides 11

Rochester Red Wings 6

Silver Stadium

Rochester, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.