July 5, 1930: Black baseball comes to Yankee Stadium on behalf of the Pullman Porters

Yankee Stadium had been open for seven seasons when the summer of 1930 rolled around. The home team, featuring Babe Ruth, whose slugging changed the way major-league baseball was played, had brought its New York fans four American League pennants and three World Series championships in those years. When the Stadium wasn’t being used by the Yankees, it was sometimes rented out for professional and college football games, prizefighting, and the annual Knights of Columbus track and field meet. But it had never hosted a game between Black major-league teams.

Yankee Stadium had been open for seven seasons when the summer of 1930 rolled around. The home team, featuring Babe Ruth, whose slugging changed the way major-league baseball was played, had brought its New York fans four American League pennants and three World Series championships in those years. When the Stadium wasn’t being used by the Yankees, it was sometimes rented out for professional and college football games, prizefighting, and the annual Knights of Columbus track and field meet. But it had never hosted a game between Black major-league teams.

That changed on July 5, 1930, when New York’s Lincoln Giants played a doubleheader at the Stadium against the Baltimore Black Sox. The Yankees, like other professional baseball clubs, charged rent for the use of the ballpark. But this one was on the house, although the benefactor and recipient couldn’t have been more unalike. The Yankees’ millionaire owner, Jacob Ruppert Jr., was giving away his ballpark for the day to an organization headed by a man whose goal in life was to make other millionaires miserable.

Ruppert headed a large family-owned brewery. At one time the National Guard aide de camp to the New York governor, Ruppert liked to be called “colonel.”1 He was opening the Stadium’s gates, a day after Independence Day, to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, who would use the Lincolns-Black Sox doubleheader as a major fundraiser. The Brotherhood, which became a leading African American union representing the porters on interstate passenger trains, was still struggling in 1930. But it had a fiery president in A. Philip Randolph. A determined union organizer and a Socialist political candidate, he had been an avowed pacifist in World War I, when someone in President Woodrow Wilson’s Cabinet gave him a nickname, too: “the most dangerous Negro in America.”2

There would seem to have been nothing that connected Ruppert with Randolph and the Porters union. But they shared a relationship to the dominant political machine in New York, the Democratic Party’s Tammany Hall. Although its power was waning, Tammany still ruled the city. Ruppert had served four terms in Congress backed by the machine, but it did not exist just to boost rich men into office. A major Tammany policy was to provide aid — jobs and household relief — to immigrants and the disadvantaged, in return for their votes. The city’s African Americans were among those brought into the bargain.

Among the influential Tammany Blacks was Roy Lancaster, the Brotherhood’s secretary-treasurer, also in charge of the union’s fundraising events. It would have seemed nearly impossible for a struggling Black union to get permission to use the Stadium. Brotherhood official C.L. Dellums later recounted that Lancaster thought so too, but that didn’t discourage him: “I remember Roy telling me [Ruppert’s] name and that he couldn’t be reached. No Negro seemed to have a chance to get anything put on in that park — for free, particularly. But Roy had enough connections to get that park.”3

The matchup for the doubleheader would have been appealing to New York’s Black baseball fans under any circumstances. Negro League ball in the East had collapsed when the American Negro League went out of business in 1929, but its teams played on, often against each other. The Black Sox had a 24-20-2 season record against Black major-league-level teams. The Lincoln Giants were even better at 41-14-1. The teams played a doubleheader at the Giants’ home field, the Protectory Oval in the Bronx, on July 4 (the Giants won both games), and prepared for the games in the big time, Yankee Stadium, the next day.

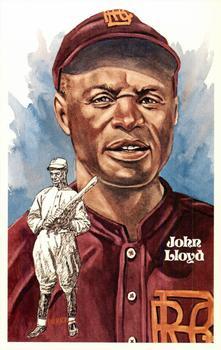

The teams were both star-studded. The first basemen, the Lincolns’ John Henry Lloyd (also the manager, and, at age 46, the team’s third-best hitter at .381) and the Black Sox’ Jud Wilson (their best hitter at .433) both eventually wound up in the Hall of Fame. The Giants had an all-star outfield of Fats Jenkins in left, Clint Thomas in center, and Chino Smith in right. The Black Sox infield, with Dick Lundy at shortstop, Frank Warfield at second, and Bill Riggins at third in addition to Wilson, was first-class too. But this was not all. Baltimore had slugger Rap Dixon, one of the hitting stars of the doubleheader, in left field and the Giants had the well-known Rev Cannady and Julio Rojo at second base and catcher, respectively.

Baltimore jumped out to a 2-0 lead in the top of the first inning of the opener when Dixon homered off Lincoln’s starter, Bill Holland. The Giants tied the game in the third, and the Black Sox scored two in the top of the fifth to go ahead again. But Baltimore starter Willis Flournoy was finished. His relief, Bun Hayes, continued to give up Giants hits, 14 in all, including two homers by Chino Smith, who also hit a triple. The Giants put four runs over in the bottom of the fifth, one in the sixth, and six in the seventh as they coasted to a 13-4 win. Holland settled down and pitched a complete game. He allowed only five hits, although he walked seven. Riggins’ double and two singles tied Smith for the team hit lead. Dixon had a double to go with his homer.

In the nightcap, Baltimore again scored two in the top of the first, when Dixon again homered. Powered by his bat (he hit another homer in the fourth), and the stick of Wilson, who had three singles, the Black Sox never trailed, and won, 5-3. Smith again was the hitting star for the Lincolns, with a double and triple. He tried to stretch the triple into an inside-the-park home run, which would have tied him with Dixon in the day’s homers, but he was thrown out at the plate.4

Black Sox right-hander Laymon Yokely, who had been knocked out of the first game on July 4 in the fourth inning, came back and threw a complete game for the win, which wasn’t nailed down until two were out in the bottom of the ninth. The Lincolns’ slugging outfielder-pitcher Red Farrell pinch-hit for losing pitcher Connie Rector and smacked a drive to the short outfield fence in right that Ruth had cleared so many times. Farrell’s hit would have eked into the stands but for the extra effort of Black Sox right fielder Script Lee. Lee was a thin six-footer with long arms,5 which stood him in good stead as he made a leaping grab of Farrell’s shot at the fence.

Lancaster and the Brotherhood had not just arranged an exciting doubleheader. In between games there were footraces featuring local runners. The best-known contestant wasn’t a track star, though. The nimble actor and tap dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson won one of the 100-yard dashes, running backward (but with a 25-yard head start). There was music, too, from the famous all-Black 369th Infantry Regiment band.6

The published attendance was as high as 20,000, a highly impressive turnout for a Black baseball game in New York. The Brotherhood announced a profit of $3,500, an amount equal to $57,200 in today’s purchasing power.7 Most of the press coverage of the doubleheader was about the games’ heroics (and those of Bojangles and the other racers). However, William G. Nunn, the Pittsburgh Courier sports editor, pointed out the afternoon’s enduring meaning: “But, in the days of our old age, we’ll look back upon Yankee Stadium, July 5, 1930, as one of the red-letter days of our lives.”8

The Stadium, in fact, had many more red-letter days for Black baseball in its future. The Lincoln Giants and the Homestead Grays played a series in September that, in the absence of a league in the East, was dubbed a “championship.” Six of the games, again brokered by Lancaster, were played at the Stadium. By the time the Negro Leagues were fading from the scene in the mid-1950s, a total of 225 games involving at least one Black team had been staged in the Yankees’ ballpark.9 Satchel Paige won 11 games at the Stadium, and Josh Gibson hit seven home runs there, among other heroics over the years.10 Yankee Stadium ranks with Chicago’s Comiskey Park, home of the annual Negro Leagues East-West All-Star game, as the most important White major league venue for Black ball.

Sources

Negro League player statistics were not always reliably and completely compiled at the time the games were actually played. But efforts have been made in recent years to use box scores and game stories to retroactively compile annual stats. The team won-lost records and individual batting averages cited here are from the Seamheads.com Negro Leagues Database, as of August 2021. The database is considered the most complete of the efforts to re-create Negro League statistics, but it is an ongoing project, and the numbers cited here may change in the future.

Notes

1 “Ruppert, Owner of Yankees and Leading Brewer, Dies,” New York Times, January 14, 1939; Dan Levitt, “Jacob Ruppert,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/b96b262d; Elizabeth L. Bradley, Knickerbocker, the Myth Behind New York, (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2009), 121-23.

2 Larry Tye, Rising from the Rails: Pullman Porters and the Making of the Black Middle Class (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2004), 114.

3 C.L. Dellums, interview by Joyce Henderson, oral history transcript for the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, at Online Archive of California (http:www.oac.cdlib.org); “Roy Lancaster ‘Puts Over’ Big Benefit Event,” New York Age, July 19, 1930.

4 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Stars Rise to Miracle Heights in Big Game at Yankee Bowl,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 12, 1930.

5 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Stars Rise to Miracle Heights in Big Game at Yankee Bowl”; Script Lee page, Seamheads.com Negro League Database, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=lee–01scr.

6 “‘Bojangles’ Wins, but Phil Edwards Is Beaten in Half-Mile Handicap at Yankee Stadium Porters’ Benefit,” New York Age, July 12, 1930; “Thousands at Yankee Stadium,” New York Amsterdam News, July 9, 1930;

William G. Nunn, “Diamond Stars Rise to Miracle Heights in Big Game at Yankee Bowl.”

7 Lucien H. White, “Roy Lancaster ‘Puts Over’ Big Benefit Event,” New York Age, July 19, 1930; “How Much is a Dollar from the Past Worth Today?” Measuringworth.com, https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday.

8 William G. Nunn, “Diamond Stars Rise to Miracle Heights in Big Game at Yankee Bowl.”

9 Jim Overmyer, “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium: The House that Ruth Built and Satchel Furnished (with Fans),” in Black Ball, a Negro Leagues Journal, Vol. 7 (McFarland, 2014): 6.

10 Jim Overmyer, “Black Baseball at Yankee Stadium”: 15.

Additional Stats

Lincoln Giants 13

Baltimore Black Sox 4

Baltimore Black Sox 5

Lincoln Giants 3

Yankee Stadium

New York, NY

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.