June 18, 1927: Lucky Lindy helps Cardinals raise pennant as Rogers Hornsby returns to Mound City

Charles Lindbergh’s nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic in May of 1927 brought him overnight worldwide acclaim. No more than a thousand well-wishers saw the former stunt pilot take off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, but as many as 150,000 were on hand when his Spirit of St. Louis touched down in a Paris airfield. Millions across Europe and the United States celebrated his achievement with an unbridled enthusiasm matched only by VE Day near the end of World War II.

Charles Lindbergh’s nonstop solo flight across the Atlantic in May of 1927 brought him overnight worldwide acclaim. No more than a thousand well-wishers saw the former stunt pilot take off from Roosevelt Field on Long Island, New York, but as many as 150,000 were on hand when his Spirit of St. Louis touched down in a Paris airfield. Millions across Europe and the United States celebrated his achievement with an unbridled enthusiasm matched only by VE Day near the end of World War II.

Once back in the States, Lindbergh received the first-ever Distinguished Flying Cross from President Calvin Coolidge in Washington.1 In New York, he collected $25,000 for winning the Orteig Prize challenge and was given a ticker-tape parade that drew 4 million spectators.2 From New York Lindbergh flew to his adopted home of St. Louis3 for another day in his honor and to help the Cardinals celebrate their 1926 World Series championship, the first in franchise history.4

Lindbergh Day in St. Louis, Saturday, June 18, kicked off with a seven-mile parade through the city. “Slim,” as the slender aviator was called by many,5 rode triumphant in a “flower-decked” white convertible with a military escort at his side and a trio of Army dirigibles above.6 Upward of a half-million admirers lined the parade route, which ran through “a confetti and paper flake blizzard” in the downtown business district.7

After a midday break, Lindbergh arrived at Sportsman’s Park, “announced by the nearing chorus of noise outside the park.” His entrance triggered “a deafening and well-nigh maddening din” from a capacity crowd of “enthusiasts … gathered to meet the idols of the sport world.”8

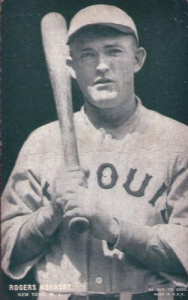

The 25-year-old pioneer wasn’t the only returning hero visiting Sportsman’s Park that weekend. Rogers Hornsby, a former Cardinals icon, was playing in St. Louis for the first time since being traded the previous offseason.

Hornsby had managed the Cardinals to victory over the New York Yankees in the 1926 World Series, following a season in which he’d battled negative publicity over an unpaid horse-racing gambling debt9 and a declining batting average. (After winning six consecutive National League batting titles, his average had dropped from .403 to .317 in what was his age-30 season.) In the end, it was Hornsby, the “Rajah of Swat,” who tagged out Babe Ruth, the “Sultan of Swat,” foolishly trying to steal second with two out in the top of the ninth in Game Seven, securing the championship for St. Louis.10

After the World Series, Cardinals principal owner Sam Breadon, fed up with his blunt and combative manager, initiated Hornsby’s trade to the New York Giants for their disgruntled second baseman, Frankie Frisch, who was unhappy with his own blunt and combative manager, John McGraw.11 Cardinals fans were outraged, but Frisch’s performance had his new manager, Bob O’Farrell, and some in the press convinced that the club was better off without Hornsby.12

Each of them fiercely competitive, Hornsby and Frisch were thriving with their new clubs.13 Hornsby entered the St. Louis series hitting .366, with a league-leading 49 runs scored and 10 home runs. Frisch was hitting .365, with 7 triples, 15 stolen bases, and an errorless chances streak to open the season that had reached 128.14

The Cardinals (29-20) sat in third place, three games out of first place, as they prepared to meet the Giants, who were four games behind them, in fourth place.

The day of the series opener, McGraw dropped a bombshell; Hornsby would take over as Giants manager in 1928.15 Sportswriter Bill Hanna of the New York Times affirmed McGraw’s decision. “Hornsby is one of the finest men we ever had on our club. You can always get it straight from Roger. He is frank, honest and has done much for the game.”16

Despite additional accolades from Cardinals fans, who “roared [their] appreciation” during a pregame ceremony, Hornsby fell flat in the opener, as the Giants lost on a two-hit shutout by Cardinals knuckleballer Jesse Haines.17 The Giants rebounded in game two behind a barrage led by first-year regular Bill Terry, 3-for-5 with a home run, triple, and four RBIs, and Hornsby, 4-for-4 with a home run and four RBIs as well.

Paused for a day while Mound City readied itself, the series was set to resume with “Lucky Lindy”18 in Sportsman’s Park.

Moments after his tumultuous entrance, Lindbergh was once again leading a parade, this time to the center-field flagpole. He was joined by a delegation that included Secretary of War Dwight Davis, St. Louis Mayor Victor Miller, National League President John Heydler, Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, Breadon, and members of the 1926 Cardinals squad, including Hornsby. “[Tugging] on the rope like a sailor,” Lindbergh raised the American flag, followed by the World Series championship pennant “with its triumphant red bird” and the NL pennant.19

His flag-raising duties complete, Lindbergh held court at home plate. He shook hands and distributed “diamond-set” rings, emblematic of the Cardinals’ championship. Ironically, the first to receive a ring was Hornsby, followed by his replacement as St. Louis skipper, 1926 NL MVP O’Farrell, the catcher whose Game Seven throw had gunned down Ruth.20 President Heydler in turn presented Lindbergh with a gift: a lifetime pass to any NL ballpark.21

As Lindbergh retired to a box decorated with flags and bunting near the Cardinal dugout, St. Louis ace Grover Cleveland Alexander took the mound. The St. Louis Star hailed O’Farrell’s choice, saying it “[made] the day a perfect one from a baseball standpoint.” Alexander’s epic ninth-inning save in Game Seven of the 1926 World Series had seemingly rejuvenated the 40-year-old’s career, evident in his 7-3 record with a 2.36 ERA that was second in the league.

Opposite Alexander was knuckleballer Freddie Fitzsimmons, 5-4 with a 3.81 ERA. He’d closed out the Giants win two days earlier, coming in to retire Wattie Holm in the middle of an at-bat, with two out and two runners on.23 In his last start against the Cardinals, on May 13, Fitzsimmons surrendered hits to the first four batters (along with a Frisch stolen base) and was yanked without recording a single out; it was the worst start of his then three-year career.

The Giants broke through first, scoring a pair of runs in the second on singles from Terry, Travis Jackson, who’d missed the first month of the season after an appendectomy, and newcomer Zack Taylor, whose hit earned him his first two RBIs since coming to the Giants in a trade with the Boston Braves a week earlier.

The Cardinals responded in the bottom of the inning. Holm opened with a double that “whistled down the left foul line” and scored on a triple by future Hall of Fame manager Billy Southworth. A single to center by O’Farrell’s successor behind the plate, former Giant Frank Snyder, chased Southworth home, tying the score at 2-2.24

In the Cardinals third, leadoff batter Taylor Douthit hit a bloop double to right field and Frisch scorched a grounder too hot for third baseman Freddie Lindstrom. RBI-machine Sunny Jim Bottomley followed by “Lindberghing” a three-run home run into the right-field bleachers.25 The blast sent Fitzsimmons to the showers in favor of Dutch Henry, a left-hander recently bumped from the Giants rotation. Henry stemmed the tide, working around Southworth’s one-out ground-rule double that “rolled into a cordon of police” down the left-field line.26

Lindbergh left the ballpark after the third inning for the next commitment on his hectic schedule. The New York Times noted that Lindbergh paid more attention to balls hit out of play than anything else during his time at the game, suggesting he harbored the same dream as many a fan: catching a foul ball.27

The Giants clawed back a run in the fourth on a Taylor double that scored Edd Roush, and another in the fifth when Lindstrom’s triple chased St. Louis native Heinie Mueller home. Lindstrom tried to score on Hornsby’s hard grounder to short but was nailed at the plate on a “perfect throw” by slick-fielding shortstop Tommy Thevenow.28

Inspired by his teammates’ stellar defense, Alexander retired the Giants in order in the sixth and picked off Lindstrom on a delayed steal attempt to end the seventh. In the eighth, with Hornsby at third after doubling and advancing on a Terry groundout,29 Alexander struck out Jackson, “usually poison for the Cardinals,”30 looking at a sweeping curve to end the inning.

The Cardinals tacked on another run in the eighth on a single by Southworth and Les Bell’s ground-rule triple to right field.31

Alexander retired the Giants in order in the ninth, the final out coming on a popup from light-hitting 18-year-old pinch-hitter Mel Ott.32 With that, “Old Pete” had his 335th career victory, third all-time among NL pitchers.33

The Cardinals were denied the pennant by a Pittsburgh Pirates squad that was then steamrolled by the Yankees in the World Series. Frisch and Hornsby finished second and third in the NL MVP race, respectively.34 Alexander became a 20-game winner for the ninth and final time in his career.

Hornsby never got the chance to manage the Giants in 1928. His abrasive personality and gambling habits prompted his exile to the Boston Braves via trade before spring training began.35

Exactly one month after this game, Charles Lindbergh was promoted to the rank of colonel in the US Army Air Corps Reserve.36 On January 2, 1928, he was named Time magazine’s very first Man (now Person) of the Year.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted game summaries and descriptions of Lindbergh Day events in St. Louis published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis Star, and New York Times, as well as C. Paul Rogers III’s SABR biography of Rogers Hornsby, Fred Stein’s SABR biography of Frankie Frisch, Jan Finkel’s SABR biography of Pete Alexander, and Greg Erion’s SABR biography of Travis Jackson. Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Stathead.com websites also provided pertinent material.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/SLN/SLN192706180.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1927/B06180SLN1927.htm

Notes

1 Lindbergh received the Distinguished Flying Cross on Saturday, June 11, a day designated as “Lindbergh Day” by President Coolidge. Charles G. Ross, “Lindbergh Decorated by the President After Colorful Ceremonies and Roaring Welcome from Multitude of Spectators,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 12, 1927: 1; “To Be a ‘Lindbergh Day,’” Kansas City Times, June 4, 1927: 1.

2 The Orteig Prize was offered in May 1919 by New York hotelier Raymond Orteig to the first Allied pilot to fly nonstop from New York to Paris, or vice versa.

3 According to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, over the previous three years Lindbergh, who was born in Detroit and grew up in Little Falls, Minnesota, and Washington (his father was a congressman from Minnesota), “never looked on any place as home except St. Louis.” Harry B. Burke, “Lindbergh, Anything but Glum, Is Sharp Match for Reporters,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 18, 1927: 1.

4 Planning for a Lindbergh Day in St. Louis began within days of his Paris landing, led by a 250-person committee. Souvenirs of the day included an “automobile sticker” depicting Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis and two special women’s felt hat models, “symbolizing the ‘Spirit of St. Louis,’” one with a propeller and the other with the plane’s outline. The US Postal Service also first placed on sale in St. Louis for Lindbergh Day a new air-mail stamp honoring Lindbergh’s historic achievement. “Mayor Appoints 250 Persons for Lindbergh Day,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 28, 1927: 3; “Automobile Sticker for Lindbergh Welcome,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 29, 1927: 2; “Aviation Felts,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 10, 1927: 7; “Lindbergh Stamp Sale Opens With Heavy Demand,” June 19, 1927: 5.

5 “Slim” was a nickname claimed to have been given to Lindbergh by his close friend Bud Gurney. It was commonly used in St. Louis newspapers when referring to Lindbergh. Giacinta Bradley Koontz, “Slim and Bud,” January 2010, Air & Space Magazine website, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/air-space-magazine/slim-and-bud-9461697/, accessed December 8, 2022.

6 Along the way, the parade paused while Lindbergh was inducted into the Boy Scouts of America, who presented him with “a scout knife and flying insignia.” Associated Press, “Two Colonelcies Given Flier at St. Louis Fete,” Detroit Free Press, June 19, 1927: 1.

7 “Part of the Half-Million Who Saw Lindy Pass,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 19, 1927: 1; Alva Johnston, “St. Louis Roars Welcome to Lindbergh for 7 Miles; Bombards Him with Roses,” New York Times, June 19, 1927: 1.

8 Crowd figures for the game, as reported in St. Louis and New York newspapers, varied from 33,500 to 40,000. Baseball-Reference lists the game’s attendance as 45,000. According to author Scott Fekovich’s SABR biography for Sportsman’s Park, the crowd capacity after the ballpark’s mid-1920s renovation was 30,500. “35,000 Deliriously Cheer as Lindbergh Helps Raise Pennant,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 19, 1927: 1; J. Roy Stockton, “Alexander’s Pitching and Two Early-Inning Rallies Decide Game,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 19, 1927: S2, 1; Richards Vidmer, “Lindbergh Watches Cards Beat Giants,” New York Times, June 19, 1927: 1S; Scott Ferkovich, Sportsman’s Park (St. Louis) SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/sportsmans-park-st-louis/.

9 In July of 1926, the Chicago-based Collyer’s Eye reported that Hornsby had taken a “run out powder” on a $5,000 horse-racing wager he’d lost with a New Jersey bookmaker. Cardinals principal owner Sam Breadon openly disapproved of Hornsby playing the horses, and the company he kept to run bets for him. “Operator Claims Hornsby Takes ‘Run Out Powder,’” Collyer’s Eye, July 31, 1926: 8; Andrew Martin, “The Troubled Life of Rogers Hornsby: Part I,” November 27, 2011, https://seamheads.com/blog/2011/11/27/the-troubled-life-of-rogers-hornsby-part-i/, accessed December 25, 2022.

10 The “Rajah of Swat” moniker was first applied to Hornsby in 1925 as an alliterative play on Ruth’s renowned nickname, the Sultan of Swat, first noted in the press by Robert L. Ripley in early June of 1920. Later that month, the Pittsburgh Post was one of several newspapers that briefly referred to Ruth as the “Rajah of Swat” before adopting Ripley’s label (one that famed sportswriter Grantland Rice had briefly bestowed on Honus Wagner three years earlier). Lloyd Gregory, “Looking ’Em Over,” Austin (Texas) American, April 12, 1925: 8; Robert L. Ripley, “The Sultan of Swat,” Binghamton (New York) Press, June 8, 1920: 16; “Ruth Knocks Out Eighteenth Homerun and Yanks Beat Whitesox,” Pittsburgh Post, June 17, 1920: 10; “They Saw,” Buffalo Enquirer, June 17, 1920: 12; Grantland Rice, The Sportlight, “Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, February 24, 1917: 14.

11 Pitcher Jimmy Ring was sent to the Cardinals along with Frisch, but it was the exchange of Hornsby for Frisch that made the trade a shocking blockbuster. Frisch was the apple of McGraw’s eye when he joined the Giants straight off the Fordham University campus in 1919, but their relationship deteriorated when McGraw, frustrated by the team’s declining fortunes in the mid-1920s, began heaping verbal abuse on Frisch, the team captain. Red Barber, “Baseball’s Frisch-for-Hornsby as Big as Any Player Trade Ever,” August 26, 1988, Christian Science Monitor website, https://www.csmonitor.com/1988/0826/ptrade.html, accessed December 7, 2022.

12 In May, O’Farrell told an Associated Press reporter that “[t]he Cards lost nothing when they got Frisch for Hornsby.” In replying to a letter from a reader, the St. Louis Star sports editor replied, “Frisch will cover more ground, make greater plays, steal twice as many bases and hit oftener in a pinch than Hornsby could or would at his best.” Associated Press, “A Tribute to Frisch,” Kansas City Times, May 10, 1927: 13; “Cards Got Best of Deal,” St. Louis Star, June 18, 1927: 4.

13 Their competitiveness wasn’t limited to scheduled games. Tired of hearing how Frisch was the faster runner, in late May, Hornsby challenged him to a race around the bases. “Tell Frisch that I’ll race him around the bases for any side bet he wishes to name. I’ll show him and a lot of critics who is the faster man.” United Press, “Hornsby Challenges Frisch to a Race,” Dayton (Ohio) Herald, May 25, 1927: 27.

14 John J. Sheridan, “Rhem Hurls His Second Two-Hit Game and Cards Trim Robins, 5-1,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 9, 1927: 11.

15 McGraw told reporters that he was “tired of traveling,” and planned to “retire from active control of the team.” J. Roy Stockton, “Hornsby Will Pilot Giants, M’Graw Says,” St. Louis Dispatch, June 15, 1927: S2, 17.

16 “Hornsby Will Pilot Giants, M’Graw Says.”

17 During the ceremony, Mayor Victor J. Miller (mistakenly identified as Victor J. Walker in the St. Louis Star) presented Hornsby with a watch. The Rajah went hitless and allowed an error in his return. Frisch scored once, hit a double and “fielded his position flawlessly.” Richards Vidmer, “Haines Shuts Out Giants on 2 Hits,” New York Times, June 16, 1927: 31; James M. Gould, “‘Ace’ Haines Is Cards Hurler in Opening Battle,” St. Louis Star, June 15, 1927: 19.

18 This recently coined nickname for Lindbergh was based on a wildly popular song of the same name, composed soon after Lindbergh’s landing in Paris. “The Lindbergh Music Craze,” December 18, 2020, AeroSavvy website, https://aerosavvy.com/luckylindy/, accessed December 5, 2022.

19 The Cardinals’ World Series championship was the first earned by a Mound City nine since the American Association champion St. Louis Browns defeated the NL champion Chicago White Stockings the 1886 “world series.” “35,000 Deliriously Cheer as Lindbergh Helps Raise Pennant”; “After 41 Years,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 19, 1927: S2, 1.

20 Vidmer, “Lindbergh Watches Cards Beat Giants.”

21 Inscribed on the lid of the box that contained the pass was a baseball with a replica of Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis. “Courtesy of All N.L. Parks Extended to Col. Lindbergh,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 19, 1927: S2, 1.

22 Alexander’s season was going well, but coming into the game he was 36-37 lifetime against New York. Throughout his career, the Giants gave Alexander more trouble than any other team. They had the highest batting average (.277) and OPS (.690) against him of any team, he lost more games to them (43) and compiled a higher ERA against them (3.14) than against any other team, and they were the only team he posted a losing record against (39-43).

23 Fitzsimmons was retroactively credited with a save for this game by Baseball-Reference.com, but he would not have earned a save under Major League Baseball rules as defined in 2022, as he didn’t enter the game with the tying run on-base, at bat or on deck.

24 Stockton, “Alexander’s Pitching and Two Early-Inning Rallies Decide Game.”

25 Bottomley, the defending National League RBI champion, was on the way to his fourth of six straight 100-RBI seasons. His 12 RBIs during a game on September 16, 1924, still stood as a major-league record in 2022. Martin J. Haley, “‘Slim’ Is Surrounded by Notables, Including Davis, Landis, Heydler and Mayor Miller, at Ceremony,” St. Louis Globe–Democrat, June 19, 1927: 11.

26 Roughly 300 uniformed policemen had been ringing the field since the game began, as a security precaution for the large and enthusiastic crowd. They left the field after Southworth’s hit, according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. Haley, “‘Slim’ Is Surrounded by Notables.”

27 Just a few years earlier, it was rare for a major-league club to allow spectators to keep foul balls. The tide turned in 1923 after the Philadelphia Phillies had charges against an 11-year-old dismissed in a local courtroom, setting a legal precedent that spectators could keep foul balls. “Lindbergh Watches Cards Beat Giants”; Larry DeFillipo, “July 18, 1923: Phillies outlast Cubs but lose ‘landmark’ decision to 11-year-old over a foul ball,” https://sabr.org/gamesproj/game/july-18-1923-phillies-outlast-cubs-but-lose-landmark-decision-to-11-year-old-over-a-foul-ball/.

28 After Game Seven of the 1926 World Series, Pete Alexander said of Thevenow, “There’s the greatest shortstop in the world. There’s the kid who won the series.” Three days after this game, Thevenow injured his ankle so badly he was out of action for more than 10 weeks. Cardinals manager O’Farrell believed his absence cost the team the 1927 pennant. “Alexander’s Pitching and Two Early-Inning Rallies Decide Game”; Warren Corbett, Tommy Thevenow SABR biography, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Tommy-Thevenow/.

29 While Hornsby did little damage against Alexander in this game, he hit more home runs off Alexander than any other hitter did between 1915 and 1930, Alexander’s final season (7).

30 Jackson was 40-for-111 (.360) against St. Louis in 1925 and 1926.

31 Bell’s hit was ruled a triple when the ball was grabbed, while it was still in play, by a fan reaching from the stands.

32 Ott was pinch-hitting for the pitcher, Henry. Ultimately a six-time NL home-run champion, Ott carried an anemic .211/.286/.263 season slash line into this at-bat and was still a month away from his first major-league home run. Three years later, Ott hit the final home run allowed by Alexander in his 20-year career.

33 Only Christy Mathewson (373) and Kid Nichols (362) had more NL wins. Alexander retired with 348 NL victories, which still rank third all-time through the 2022 season.

34 Frisch led the league in stolen bases (48) and fielding percentage among second basemen (.979), hit over .330 for the fourth time in his career, and had the NL’s second-highest WAR (9.4). Hornsby hit .361 and led the league in runs (133), walks (89), on-base percentage (.448), OPS (1.035), and WAR (10.2).

35 Anxious to unload their troublesome captain, the Giants traded Hornsby to the perennial second-division dwellers for a backup catcher (Shanty Hogan) and an undecorated outfielder (Jimmy Welsh) whose combined career WAR would end up more than 100 points lower (22.4 vs. 127.3) than that of the future Hall of Famer.

36 Frequently identified in St. Louis newspapers on his Day as “Colonel” Lindbergh, he was officially still a captain for another month.

Additional Stats

St. Louis Cardinals 6

New York Giants 4

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.