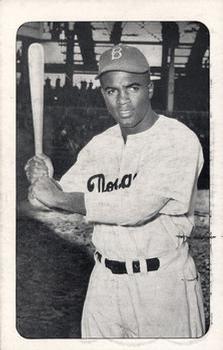

May 18, 1947: Jackie Robinson welcomed at Chicago’s Wrigley Field

Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers came to Chicago’s Wrigley Field in mid-May of 1947 amid a grand experiment that changed professional sports, opening the gates to a stream of talented Black athletes and advancing the cause of racial justice. The experiment proved an emotional stress test for Robinson, the Dodgers team, and the National League. The result changed the fabric of America.

The pressure that Robinson endured during his early seasons is well documented. But there were glimpses of hope in the unity and progress that Robinson represented, such as what happened on May 18 in Chicago, the heart of America. Chicago was distinct among National League cities in its cooperation with baseball’s integration. Several attendees of Robinson’s Wrigley Field debut later used their influential careers to commemorate Robinson. Their memories provide vignettes of the game.

Robinson’s major-league debut had occurred over a month earlier, on April 15 at the Dodgers’ home ballpark, Ebbets Field. The trials Robinson faced early on set the tone for what he endured for the remainder of the 1947 season. On April 22 Phillies manager Ben Chapman verbally unloaded on Robinson in a well-publicized racial bashing. The backlash to Chapman’s epithets later led him to seek a photo op with Robinson for damage control.1

In May, the team’s grand experiment in integration went on the road, as Robinson played outside New York City for the first time.2 The Dodgers faced Chapman and the Phillies again in Philadelphia, visited baseball’s southernmost city of Cincinnati, then played in Pittsburgh, Chicago, and finally St. Louis, where Robinson was not allowed to sleep at the same hotel as his teammates and the Cardinals threated to strike if he played.3

After playing in front of 27,164 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field and 34,184 at Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field, the Dodgers arrived in Chicago with Robinson riding a 14-game hitting streak. Chicago was in third place with a record of 14-11, with the Dodgers at 13-12 and in fifth place in the early-season standings.

Chicago was the home of hundreds of thousands of Black people who moved north during the Great Migration, seeking economic opportunity and an escape from the segregated confines of the South. Chicago was once a hotbed of Black baseball, the home of Rube Foster, who had founded the Negro National League in 1920. In 1900, 30,000 Black residents called Chicago home. By 1945, that number had grown to 350,000.4

Settling mostly on the South Side for its numerous factory jobs, and redlined from other neighborhoods, Chicago’s Black population was unified by the Chicago Defender, a highly influential African American newspaper that enjoyed national popularity due to talented writers and a robust distribution system.

But Blacks and Whites rarely mixed in Chicago in 1947, certainly not on the North Side near Wrigley Field. As the city prepared for Robinson’s arrival, Fay Young, writing for the Defender, urged Black community members to be on their best behavior, as they were being tested as much as Robinson. “The telephone booths are not men’s washrooms. The sun and liquor, even if you drink it before you head north, won’t mix.” He warned: “The negro fans can do more to get Jackie Robinson out of the major leagues than all the disgruntled players alive.”5

When the Cubs squared off with the Dodgers, Chicago’s Black baseball fans came in droves. They came by bus, train, and car. Wrigley Field set a paid-attendance record6 with 46,572,7 with upward of 20,000 unable to get into the ballpark. Buses dropped off Wrigley-bound passengers blocks away due to congestion around the ballpark. Dressed in their Sunday best, they showed adoration and support for Robinson and cheered him for striking out at his first at-bat.

In attendance were spectators who would later be influential in honoring Robinson’s legacy. Twelve-year-old Allan “Bud” Selig, future commissioner of baseball, took the train from Milwaukee along with a neighborhood pal, future US Senator Herb Kohl.

Fourteen-year-old attendee Mike Royko later blossomed into a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist. Writing for the Chicago Sun-Times on the day Robinson died in 1972, Royko reflected:

By noon, Wrigley Field was almost filled. The crowd outside spilled off the sidewalk and into the streets. Scalpers were asking top dollar for box seats and getting it.

I had never seen anything like it. Not just the size, although it was a new record, more than 47,000. But this was twenty-five years ago, and in 1947 few blacks were seen in the Loop, much less up on the white North Side at a Cub game. …

The whites tried to look as if nothing unusual was happening, while the blacks tried to look casual and dignified. So everybody looked slightly ill at ease.

For most, it was probably the first time they had been that close to each other in such great numbers. …

[Robinson] swung at the first pitch and they erupted as if he had knocked it over the wall. But it was only a high foul that dropped into the box seats. I remember thinking it was strange that a foul could make that many people happy. When he struck out, the low moan was genuine.8

Robinson’s presence was inescapable during the game, but his performance was less of a factor in his team’s victory. Four hitless at-bats ended his hitting streak at 14 games. He struck out twice – once with the bases loaded and no outs, during the Dodgers’ four-run seventh inning rally that clinched the win. He also committed one “harmless” error out of a dozen chances.

The Cubs scored two in the fourth and Johnny Schmitz was rolling along with eight strikeouts through six innings. But the Dodgers scored four runs in the seventh after starting the inning with Pee Wee Reese’s walk, 19-year-old Tommy Brown’s pinch-hit single, and Eddie Stanky’s bunt single. Schmitz got Robinson to look at a called third strike for the first out. He got ahead of Pete Reiser with two strikes, but the Dodgers center fielder fouled off several pitches, then dropped a fly ball inside the left-field foul line for a double, scoring Reese and Brown to tie the game.9

The Dodgers followed Reiser’s double by turning two intentional walks, a run-scoring groundout, and a bases-loaded walk into two more runs for a 4-2 lead. Reliever Hugh Casey made the lead stand up with three scoreless innings to save Joe Hatten‘s fourth win of the season.

After dropping the second game of the series on May 19 before a crowd of 21,875, significantly smaller than the day before but still the Cubs’ second-biggest single-game Monday gate of 1947,10 the Dodgers left Chicago and headed south to St. Louis, anticipating the climate would be hostile. There, the Cardinals threatened to strike, but the games went off as scheduled, and Robinson “was cheered each time he went to bat and the Dodgers as a team received more vocal encouragement than they usually got at Sportsman’s Park.”11

During the 1980s, a passionate Cub fan, Jerry Pritikin, became a local legend around Wrigley Field. Pritikin became known as the “Bleacher Preacher” due to his mission to convert opposing fans into Cub fans.12 Jerry was 10 years old when he attended this Sunday afternoon game. He later reflected on the day, noting the large crowds outside and that fans brought binoculars.

Selig sat in the upper deck. “We were the only white fans up there,“ he recalled in 2004. “There was so much electricity and drama.”13

In Selig’s 2019 memoir, For the Good of the Game, he reflected further on the day. “On the ride home, I felt so many emotions. Not only was I a little wiser from my time in the upper deck, but I could see plain as day that even though Jackie went hitless, he was a great player whose presence was going to change baseball.” Selig became baseball’s ninth commissioner in 1992. In 1997 he led the movement to retire Robinson’s uniform number 42 across baseball. He instituted April 15 as Jackie Robinson Day in 2004, and since 2009 every player has worn number 42 on that date.

Selig’s childhood neighbor Kohl served as a US senator from 1989 to 2013. In 2003 he cosponsored a bill to award the Congressional Gold Medal to Robinson. Robinson was awarded the medal, Congress’s highest honor, posthumously in 2005, with his widow, Rachel, receiving it from President George W. Bush in a ceremony at the Capitol Rotunda.14

On the Sunday that Royko, Selig, Kohl, Pritikin, and so many more watched Robinson break baseball’s color barrier in Chicago, there were no death threats as in Cincinnati, no possibility of player strikes as in St. Louis, no phony publicity photos as in Philadelphia. Chicago acted with class.

History has focused on the stressors absorbed by Robinson and the grit required to integrate baseball. But the grace of Chicago’s Black community at Wrigley Field and the respect returned by Cub fans has gone mostly unrecognized. Today, the single-game paid-attendance record through more than a century of baseball at Wrigley Field is its enduring testament.

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes below, the author also consulted pertinent data from Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org, including the box scores below. The author also reviewed Sam Smith’s article, “A Whole New Ballgame,” from the May 17, 1987, Chicago Tribune, for background on Robinson’s Chicago debut.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN194705180.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1947/B05180CHN1947.htm

Notes

1 Marc Tracy, “69 Years Later, Philadelphia Apologizes to Jackie Robinson,” New York Times, April 15, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/15/sports/baseball/philadelphia-apologizes-to-jackie-robinson.html.

2 The Dodgers’ first 17 games in 1947 included 15 home dates and two games against the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds.

3 Jonathan Eig. Opening Day (New York, Simon & Schuster, Inc., 2007).

4 https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/long-lasting-legacy-great-migration-180960118/.

5 Opening Day, 142.

6 A crowd of 51,556 attended in 1930, on a ladies day (women got in free) and fans were allowed on the field, thus increasing its capacity.

7 “Brooklyn Bats Rout Schmitz in 4 Run 7th,” Chicago Tribune, May 19, 1947.

8 Mike Royko, “Jackie’s Debut,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 25, 1972.

9 Harold C. Burr, “Fireman Casey Pulls Dodgers’ Bacon out of Fire for Sixth Time,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 19, 1947: 11.

10 Chicago drew a crowd of 25,052 paid for its game on Monday, July 28, against Robinson and the Dodgers. (The Cubs’ biggest Monday home crowd in 1947 was 39,511 for a Labor Day doubleheader with the Reds on September 1.)

11 J. Roy Stockton, “Cardinals ‘Health Resort’ Makes Rivals Feel Better, Fans Worse,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 22, 1947: 10C.

12 Dan Epstein, “Jerry Pritikin: An Audience with Cubs’ Bleacher Preacher,” Jewish Baseball Museum, July 25, 2016, https://jewishbaseballmuseum.com/spotlight-story/jerry-pritikin-adience-cubs-bleacher-preacher/.

13 Adam McCalvy, “Selig Wanted Jackie’s Legacy to Live Forever,” Major League Baseball, accessed April 10, 2021, www.mlb.com/news/jackie-robinson-had-lasting-effect-on-bud-selig.

14 Heath Geva, “Kohl, Herb,” Members of US Congress, accessed January 3, 2021, https://memberscongress.lawi.us/herb-kohl/; “Robinson Awarded Congressional Gold Medal,” ESPN.com, March 1, 2005, https://www.espn.com/mlb/news/story?id=2002582.

Additional Stats

Brooklyn Dodgers 4

Chicago Cubs 2

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.