Q&A with SABR Deadball Stars book editor David Jones

This article was written by John McMurray

This article was published in SABR Deadball Era newsletter articles

Editor’s note: An abridged version of this interview was published in the SABR Deadball Era Committee’s October 2020 newsletter.

David Crawford Jones is a former chairman of the Deadball Era Committee and the editor of Deadball Stars of the American League, published by Potomac Books in 2006. With a master’s degree in U.S. History and a doctorate in African history, he has written extensively on the intersection of racism and popular culture.

David Crawford Jones is a former chairman of the Deadball Era Committee and the editor of Deadball Stars of the American League, published by Potomac Books in 2006. With a master’s degree in U.S. History and a doctorate in African history, he has written extensively on the intersection of racism and popular culture.

A version of his 2007 master’s thesis, “‘An Unusual Case’: Dan Shay, Clarence Euell, Gertrude Anderson, and the Limits of Hoosier Progressivism,” was published in the Magazine of Indiana History and received the 2009 Emma Lou and Gayle Thornbrough Award for the best article published on Indiana history in 2008. From 2014 to 2018, David taught African History in the Department of African American and African Studies at the Ohio State University. He currently teaches at a middle school in Columbus, Ohio.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

Q: We are now more than a hundred years beyond the end of the Deadball Era. Why is there such interest in continuing to study it, when we don’t find ourselves, say, studying football from a hundred years ago with the same vigor?

A: Baseball, I think, has been very good at sort of maintaining continuity with the past. I wrote about this idea in the Introduction to Deadball Stars of the American League. As I said there, I think there’s something special about the Deadball Era because it comes before Babe Ruth. The Deadball Era is really ended by Babe Ruth hitting home runs in New York. So the Deadball Era is a glimpse into a time period in baseball history when home runs were not king and when the ideas about the game were very different.

What I like about Deadball Era baseball is that it was before Ruth, but the rules are pretty much the rules as we know them now. You have the foul strike rule implemented by 1903, and the distance between the mound and home plate is the same as we have today. All of those rules are in place. There are still rule changes which would happen afterward, but the game that’s being played in the Deadball Era, according to the rules, is a lot like the game we play today. Yet it is so different. Exploring that difference and why the game was played that way and how it changed is interesting to me.

Also, the American League existed in the Deadball Era and the National League existed in the Deadball Era. The structure of baseball, as we know it today, was therefore coming into focus during the period. It’s like this enchanting mix of the familiar — the rules are similar, the leagues are similar — and the different. Strategies are very different, the parks are different. At the same time, a lot of the parks that have come to be beloved by baseball fans during the 20th century and up to today were built during the Deadball Era. The Deadball Era is really the time period where I see baseball becoming the national pastime, where it really is becoming a symbol of American culture. All of that, I think, helps us to understand why we love it so much and why we still do a hundred years later.

Q: You have studied the Deadball Era for more than twenty years. Does it still appeal to you with the same intensity?

A: Yeah. Yeah, it does. I wonder if the Deadball Era in some way attracts a lot of contrarians. We look at the way baseball today is played and grit our teeth. That is certainly the case for me. I really started studying the Deadball Era around the year 2000. That was two years after Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa had shattered Roger Maris’ single-season home run record and home runs were going through the roof. And I hated that. I hated the number of home runs that were being hit. I thought it was ugly baseball. And I kind of feel that way about the game being played now, to be honest. So, for me, the Deadball Era is baseball in a different form and that form is more appealing to me. As an historian, I gravitate towards the Deadball Era because I just think there’s something beautiful in it. It brings me pleasure and joy to continue to study it and to think about it.

A: Yeah. Yeah, it does. I wonder if the Deadball Era in some way attracts a lot of contrarians. We look at the way baseball today is played and grit our teeth. That is certainly the case for me. I really started studying the Deadball Era around the year 2000. That was two years after Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa had shattered Roger Maris’ single-season home run record and home runs were going through the roof. And I hated that. I hated the number of home runs that were being hit. I thought it was ugly baseball. And I kind of feel that way about the game being played now, to be honest. So, for me, the Deadball Era is baseball in a different form and that form is more appealing to me. As an historian, I gravitate towards the Deadball Era because I just think there’s something beautiful in it. It brings me pleasure and joy to continue to study it and to think about it.

Q: What areas about the Deadball Era should researchers be exploring further?

A: This is something I wish I had done when I was chairman of the Deadball Era Committee. We had done Deadball Stars of the National League, we had done Deadball Stars of the American League. Together, it was a massive undertaking, there were dozens and dozens of people involved in it. Everyone was a little bit exhausted when those two books came out.

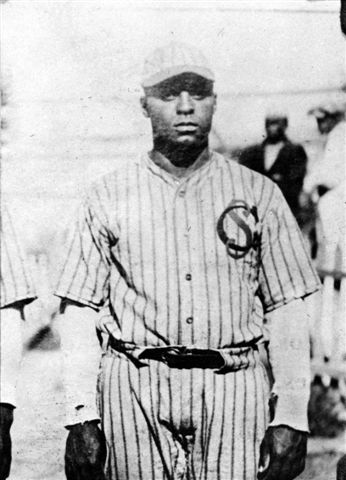

But there was something about it that sat wrong with me, that we did these two books and everyone in them was either white, or in some cases, Native American. We had done nothing to document Black baseball during that time period. Obviously, SABR has a Negro Leagues Committee that has done a lot of work in this area. But I kind of wished at the time, and I still think it would be a fruitful endeavor, to try and get the Deadball Era Committee and the Negro Leagues Committee to collaborate to examine baseball in this time period. It would a big undertaking.

It is 2020 now and the 100th anniversary of the Negro Leagues being founded by Rube Foster. Before 1920, you didn’t really have organized leagues like you do in the 1920s and the 1930s. Therefore, documentary evidence for players before that time is patchier. Nevertheless, we know that there were great Black players in the early 20th century. Some of them were from Cuba. I’m thinking of José Méndez, for instance. You also have John Henry Lloyd in the United States, Spottswood Poles, Smoky Joe Williams. There’s a lot, and there’s many more beyond the Hall of Famers and the most famous ones.

There are also other players who maybe haven’t gotten the same level of recognition but also we know were very good players. I think it would be incredibly beneficial to our understanding of baseball history and to our understanding of African-American sports to do a work on Black players during the Deadball Era. Even with the two books we did publish, we can’t honestly say we have told the story of baseball in the Deadball Era if we haven’t covered the many great Black players of that time. I think that’s definitely an area for research which remains to be explored.

Q: In reflecting on the Deadball Era, how do you think researchers and fans should view it today?

A: I think one thing we have to remember about the Deadball Era is that it was played in a time of segregation, obviously, but it was also a time where segregation, in many ways, was becoming much harsher. Given that, I think we need to be aware of the climate in which baseball was being played at that time.

A: I think one thing we have to remember about the Deadball Era is that it was played in a time of segregation, obviously, but it was also a time where segregation, in many ways, was becoming much harsher. Given that, I think we need to be aware of the climate in which baseball was being played at that time.

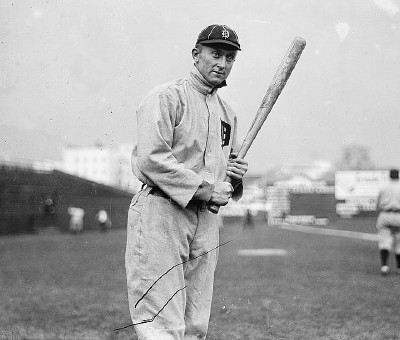

In the past, we have had this tendency to talk about race in the Deadball Era in the context of Ty Cobb, for instance. There is this debate about how racist Ty Cobb or to what degree other players were. To me, those aren’t really the best questions to be asking. I think we instead need to be looking at baseball by trying to see the totality of it. Not just individual players and how they perceived race but, rather, how the institution of Major League Baseball operated in that context of intensifying segregation.

I think about 1901, when John McGraw tried to pass off a Negro Leagues player as Native American. Those are the types of events we can look at more closely to get a better understanding of how baseball during the Deadball Era dealt with racial topics. I would hope that we do it in a way that’s not about trying to determine who was racist and who was not and more to looking at it in the context of how baseball was a major institution of American life in this time period, an era of intensifying segregation. We should think about what we can learn about baseball in this time period by thinking about segregation and, also, what we can learn about American segregation by looking at baseball.

Q: What do you think we can learn about American segregation, as you describe? Was baseball a leader or a follower?

A: That is a really good question. I don’t know the answer to that. I suspect that in some ways, it was probably both, just as I think when you have the era of integration, I think baseball was both a leader, certainly with Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, and also, in some ways a follower, in that those things didn’t come out of nowhere and there was a struggle for integration that was underway at that time. I suspect when you look at Major League Baseball during the Deadball Era, it’s a similar story.

Overall, baseball was probably more of a follower than a leader because I just don’t get the sense that baseball is the one setting the tone for race in America. At the same time, I think we have to acknowledge that baseball was either the most popular sport in America at this time or the second most popular, if you think boxing was the most prominent sport in American life, and so therefore it did have an impact on racial attitudes and practices.

I believe we have to compare it to other fields of American life. In the case of baseball, I think you can say it’s completely segregated and much of American life at that time was segregated but not all of it. You have Jack Johnson, the Black heavyweight boxer fighting for the heavyweight championship of the world against a series of white boxers. So it wasn’t an impossibility that Blacks and whites could compete against each other. It was just very rare. When I look at baseball, I would say that it is more that baseball had the opportunity to be a leader in the sense of opening a pathway for integration in American society or pushing back against the forces of segregation that were growing in that time period and that it failed to do so.

Q: Whose fault was it? Was it overt or covert?

A: I have always been sort of unsatisfied with the details that we actually have. For instance, you have the story about John McGraw trying to pass Charlie Grant, the Negro League player, as Chief Tokohama, trying to pass him off as Native American. We know the other teams and owners complain, and then McGraw essentially gives up. McGraw gives up on the idea that I’m going to have this man play for the Baltimore Orioles.

So I start to wonder, ‘okay, what if he hadn’t given up’? What if he’d said: ‘show me the rule that says I can’t have a Black player. I want to win.’ He could have done that, but he didn’t. It kind of makes me wonder: what are the conversations that are happening behind closed doors in baseball at that time and who is making the decisions?

Considering that there was strict racial segregation in that time period, I don’t think it’s right to mainly focus on the players. I think we predominantly have to focus on the owners and on the league officials, the ones who are not pushing this issue who are holding off on the idea of integration. The other thing we have to think about is, while it’s true that Black Americans could not play in Major League Baseball, we know that Native Americans could. Why is that? Why was it acceptable for Chief Bender or Chief Meyers or all these players who were given racist nicknames to play in Major League Baseball, but African-Americans couldn’t?

Those are questions that I don’t think have been fully answered. There is more research we can do into trying to understand how segregation was enforced in Major League Baseball during the Deadball Era and who was responsible for enforcing it. I have always felt that as baseball historians, we have often approached the subject from the perspective of: ‘well, of course, it was segregated. It was America in the early 20th century.’ There is truth to that, obviously. America was a very racially segregated society. I still think we can look at what was happening in baseball, where Chief Bender was allowed to play but Charlie Grant was not allowed to play.

Maybe there is no documentary evidence. It is a very challenging question. I believe we need to look at baseball history in this time period from a perspective of race in an innovative way. We have paid attention to what extent Ty Cobb was racist, and I don’t think that’s a very useful debate to have. I don’t think it’s a very important question to answer. I think a much more important question to answer would be this question of why Native Americans can play and why a Cuban like Armando Marsans can play but Charlie Grant can’t play.

To answer that question, I think historians of the Deadball Era are going to have to engage more thoroughly with histories of race in America in this time period and put baseball in conversation with the histories that have been written about segregation and other facets of American life. There is an opportunity for someone to write on this subject which might give us a better understanding in the future.

Q: Were there any players who were bucking the system and saying we should integrate at this particular time or who were challenging authority or who expressed publicly that they wanted an integrated league at the time?

A: Someone may be more up to date on this than I am. Nothing immediately comes to mind. I do know there were white players who were very complimentary of Black players and who knew that they could play. Whether they extended that to the point of saying ‘we should have an integrated league, it’s ridiculous that we are not playing in the same league as these players,’ that I do not know.

A: Someone may be more up to date on this than I am. Nothing immediately comes to mind. I do know there were white players who were very complimentary of Black players and who knew that they could play. Whether they extended that to the point of saying ‘we should have an integrated league, it’s ridiculous that we are not playing in the same league as these players,’ that I do not know.

I know, for instance, that Honus Wagner had very complimentary things to say about Black players. We know that John McGraw had very complimentary things to say about Black players. But I don’t get the sense that there was like, pardon the analogy, a Colin Kaepernick who was willing to put their career on the line or themselves on the line to fight for that. There may be somebody who did that, I’m not aware of it if it’s true, if they actually did. But I do know that there were a number of people who knew that there were Black players and Cuban players who could play and who should have been in the Major Leagues in the sense that they were good enough to be in the Major Leagues but weren’t.

So another area of research might be to look at the examples of white players against Black players and look more at the stories that were published about those games. That’s where you start to get the quotes about different people, saying ‘this guy over here can really play. I’m surprised at how good he is. He could easily be in the Major Leagues right now.’ Those kinds of quotes, you find them from the encounters where you did have white players and Black players facing each other in exhibitions. That is another area for research that I think we could do more on than we have at this point.

Q: If some contemporary manager, let’s say McGraw, had signed a Black player and brought him to the active roster, what do you think would have happened?

A: Wow. Counterfactual history is often difficult. You think about what happened in 1947, when Branch Rickey brought Jackie Robinson to the Major Leagues. A number of his teammates didn’t want to play with Robinson. You had opposing teams that didn’t want to play the Dodgers. You had opposing managers who abused Robinson and opposing pitchers who abused him as well. And that was in 1947. That was 30 or 40 years after the Deadball Era, in a time right after the Second World War where African-Americans had fought for the United States, died for the United States, where there had been a global struggle against fascism, against Nazi ideology. And, still, there was a huge uphill fight that occurred.

I suspect if integration had happened in the Deadball Era, it would have been that same way but even more intense. Think about what happened to Jack Johnson when he won the heavyweight championship of the world, all the abuse he took. I would say that at a minimum you would have had players from whatever team the Black player was playing for, let’s say it was Charlie Grant, they would simply have refused to play. You would have had a lot of opposing teams that would have refused to play. You would have had significant harassment of that player and that team everywhere they went.

Also, I don’t know if you would have had that the sort of societal context in which there would have been enough people willing to stand up to that harassment to actually make it work. Just the fact that McGraw bailed on the idea once he was called out with the whole Chief Tokohama thing shows that the fortitude was not there to make it a successful project.

I do think that if it had been attempted and failed, that itself still would have moved the struggle forward. Even if you had a Black player brought to the Major Leagues which led to massive conflict and controversy which forced the team to back off on keeping that player, I think the struggle would have been worth it at the time to advance the cause of racial equality in this country. It is a shame it didn’t happen even though it almost certainly would have failed.

Q: Oscar Charleston, born in 1896, would likely have made it to the Major Leagues near the end of the Deadball Era. If he had, how do you think he would have performed in the Major Leagues?

A: He would have been right there with Cobb as the best player in baseball, I think. During quarantine, I read Jeremy Beer’s biography of Charleston. I came away convinced that Charleston was one of the five or ten best players in baseball history. When I read about his speed, his power, his throwing arm, it was kind of like if Willie Mays had come to the Deadball Era. Charleston was 20 years old in 1916 so Cobb at that point would have been maybe a little bit past his peak. Within five years, Charleston probably would have been there with Ruth as one of the two best players in baseball.

A: He would have been right there with Cobb as the best player in baseball, I think. During quarantine, I read Jeremy Beer’s biography of Charleston. I came away convinced that Charleston was one of the five or ten best players in baseball history. When I read about his speed, his power, his throwing arm, it was kind of like if Willie Mays had come to the Deadball Era. Charleston was 20 years old in 1916 so Cobb at that point would have been maybe a little bit past his peak. Within five years, Charleston probably would have been there with Ruth as one of the two best players in baseball.

Q: What other Black baseball stars would have made the most impact in the Deadball Era?

A: There’s a lot. I definitely think John Henry Lloyd, who Honus Wagner was very complimentary of when he saw him play. I definitely think José Méndez, the pitcher from Cuba, would have been one of the top pitchers in baseball. Rube Foster, before he became an executive, of course, was a very good pitcher himself. We know Foster did very well in some of the exhibitions he pitched against white Major Leaguers. He would have had a big impact. I’ve always sort of being fascinated by Spotswood Poles. He was this player in the second half of the Deadball Era who was compared frequently to Ty Cobb. I would have loved to have known what he could have done in the Major Leagues. There’s a lot, honestly. There’s a lot. Charleston’s probably the first, but you have Lloyd and you have Mendez and Foster and others as well.

Just look at what happened when Black players finally did get the opportunity to play in the Major Leagues. You have Willie Mays and Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks and Frank Robinson. Suddenly, all these great Black players are dominating the game. To some extent, that would have been the case in the Deadball Era as well. They may not have dominated to the same extent just because in the Deadball Era, we also have to remember that most African-Americans were still living in the South, and baseball was not as established in the South as it was in the North at that time. But I think that the players we know about, the great Negro League or Black players that we know about, would have done very well in the Major Leagues. The players who did end up in the Hall of Fame would have probably still have ended up in the Hall of Fame, and there probably be a few others who haven’t gotten into the Hall of Fame that would have gotten there if they’d had the chance.

Q: Do we view the records of the Deadball Era as being valid, having been accumulated in a segregated time?

A: To me, records are always valid. They’re simply statistical records of things that occurred. They are valid in the sense that they occurred. The real question is: how do we interpret them? For that, I believe we need to think about the quality of competition, including in the Negro Leagues, as well. You get some ridiculous numbers coming out of the Negro Leagues where guys are hitting .430 and are hitting a home run every six at-bats or something comparable. You have to ask: what’s the quality of the competition? That is true for all of baseball in this time period, unfortunately, because we didn’t have an integrated league.

When I look at somebody like Cobb or Walter Johnson and I say, ‘okay, he’s got a .366 career batting average and a dozen batting titles (note: 11 or 12 depending upon which source one relies). Is this something that would have occurred after 1947?’ The answer is, almost certainly not. I love ranking players, I love trying to figure out who is the greatest of all-time.

I think you look at this question: what’s the quality of competition, and how much did he dominate it? By that standard, Cobb is certainly one of the best players of all time. But Cobb was not facing the best players overall. In some cases, he is, but, in some cases, he’s facing guys that would be in the minor leagues if we had an integrated league and an integrated society. So I think the records are valid, but I think you also need to take them with a grain of salt. That is true for records which have been established in the integrated era as well. Think about the crazy strikeout numbers that pitchers get now because batters don’t care anymore if they strike out. There’s kind of a consensus among hitters that ‘if I strike out, so what? I’m trying to hit the ball over the fence. Or I’m trying to hit a double so I’m going to swing as hard as I can.’ Look at today, how many strikeouts per nine innings you get from guys like Josh Hader or Chris Sale or Gerrit Cole. Those levels would not have occurred in the Deadball Era. You would not have as many pitchers getting as many strikeouts in the Deadball Era because they would be facing hitters who would be trying to put the ball in play, no matter what. So it kind of works both ways. You always have to look at the context in which everything occurs. It doesn’t matter what era, it doesn’t matter who did it. Always, always, always look at the context and try to understand how that context impacts what they were trying to achieve.

To me, this is what makes baseball history so interesting and kind of joyful. You can look at Ty Cobb’s numbers, and you can turn around and look at Willie Mays’ numbers and you can have a debate, even though the numbers might say offensively that Ty Cobb was way better than Willie Mays. You can have a really interesting debate about which one of them was better. To me, that’s not a bad thing. I would hate it if we had a world where all the numbers were evened out and everything was easy to compare. The more that people point out ‘so this guy did this, but they had amphetamines back then,’ or ‘in this era, they had anabolic steroids, or ‘in this era, they did not have an integrated league,’ I think, ‘bring it on.’ Let’s have that debate because that is what makes baseball history, to me, so interesting.

Somehow, we have managed to have a sport where you can have such wildly different circumstances as the Deadball Era and the Steroid Era, for instance, and yet somehow we can have a conversation about Ty Cobb and Barry Bonds. There is really no other sport in the world where anyone can try to do that, to actually compare players from such wildly different eras. I think it’s wonderful to have this debate. Let’s definitely remember that all numbers are produced in a particular context and need to be taken with a grain of salt. Every single one of them.

Q: Do you believe that Deadball Era baseball should continue to maintain its currency in baseball history in spite of being played during a segregated time?

A: Absolutely. This is not to start a political argument, but I consider myself to be on the left wing of the political spectrum. Even so, I hate cancel culture. I hate the idea that somebody did something wrong and therefore ‘forget about them, they don’t matter.’ To me, embracing what somebody did, whether they’re an artist, a writer, or a baseball player does not mean embracing every belief they held or every action that they took in their lives. It just means recognizing that even if they had some terrible ideas about something, they still did this other thing really well. And the thing they did really well is worth remembering. I certainly feel that way about Ty Cobb. It is worth remembering — and celebrating, in some sense — the way that Cobb played the game of baseball.

Q: What would you say relative to the concept that race is the central issue in American life and that how someone acted on race in their time determines whether what else they did has value?

A: I think that viewpoint sucks all the joy out of life and all the humanity out of it. I’m 43 years old now. I like to think I have educated myself a lot on race over the last 25 years. I would like to think that, as a white man, I do understand many things and that I could acknowledge and confront and combat racism. I have made mistakes in my life. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t made mistakes.

What I would say to the people who argue, ‘a person did something offensive so therefore cancel them or whatever,’ is, in your own mind, whoever you are, whatever race, gender, sexual orientation or whatever, think about what is the worst thing you’ve ever done in your life. What is the very worst thing you ever did? Would you be okay being judged — your entire life, character, history, everything — being judged on that thing? If you would not be okay with it, then you need to allow some grace for the mistakes that others have made in their lives, especially those who lived in a time when racism was common and prevalent. It is ridiculous to expect a baseball player, who, in most cases, came from a particular social setting and spent his whole life thinking about baseball to be progressive on race.

I do not think that baseball players are a particularly enlightened group of people when it comes to politics, society, or culture. Baseball players play baseball. That’s what they’re really good at. And they spend a lot of time doing it. They play 162 games a year. They sit through three-hour games 162 times plus all their practices, workouts plus the offseason. They sleep, eat, and breathe baseball. That’s how they got good at it. I do not expect them to have enlightened views on politics. When they do, I’m impressed. You know, Curt Schilling has said some things about politics and religion that I really vehemently disagree with. Guess what, I don’t look to Curt Schilling for insight on the world. He was an outstanding pitcher, though.

Q: Do you view the Deadball Era as being a necessary step in integration’s course in baseball?

A: That’s a good question. Yes, only in this sense. If we want to understand how we got to integrated baseball where you have Willie Mays and Hank Aaron and Jackie Robinson and all these great Black players who enriched our game, you have to understand where it came from. Without the Negro Leagues, I don’t think we get integrated baseball. Black people could have said: ‘You know what? They’re not going to let us play this sport, we’re not going to play.’ I think that’s part of the progress that took place as well. The times when whites played against Blacks in exhibitions, in winter leagues in the Caribbean, and all that contributed to the eventual achievement of integration in the sport.

Yes, I do see that as an incremental progress. The only thing that kind of makes me nervous about the term ‘incremental progress’ is sometimes that’s sort of viewed as a way to say to people who are trying to make radical demands, ‘hey, that’s not how change occurs, you have to be patient, it happens slowly over time.’ That idea itself can be a barrier. I would say incremental progress is a real thing, but it does not mean we should say to people who want dramatic change that they’re wrong. I think it’s the very demand for radical change which brings about incremental progress.

Q: How do you square enjoying this era of baseball in spite of the racial makeup of the contemporary game?

A: I have a couple of friends who love baseball. If I argue with them about who the greatest player ever was, and I say ‘you’ve really got to look at Ty Cobb or you’ve really got to look at Babe Ruth because of all these things he did,’ they will say that doesn’t count because Cobb or Ruth weren’t playing in an integrated league and they dismiss it.

What I would say is, first of all, I certainly don’t enjoy the fact that the game was segregated. Loving the Deadball Era should, and hopefully does, have nothing to with the fact that all the players were white. No, the worst thing about the Deadball Era was that there were not any Black players in the league. It was the very worst thing about the Deadball Era. The Deadball Era would be so much richer and our knowledge of it so much greater if that segregation had not existed.

But if you love baseball, if you really love baseball, as a sport, if you love the poetry of the game and you love the unique aspects of the game, then the Deadball Era is great because you have all these strategies and mindsets that we don’t have as much anymore. I don’t agree with 98 percent of the things Ty Cobb ever said in his life, but if there was one player I could go back and watch based on all the things I’ve read about how he played the game, it would be Ty Cobb. I love the players who have that take-no-prisoners attitude of ‘I’m going to take out every baserunner I can, I’m going to get every extra base I can.’ There’s going to be movement and motion constantly. Today, baseball in 2020 is an integrated game, it’s a global game, and we have people all over the world playing it, but sometimes the way we play the game is so dull to me, where it’s just strikeouts, walks, home runs, long at-bats, games lasting over three hours, or everyone trying to squeeze every last inch of analytics they can out of every encounter, that’s not always enjoyable to watch. Sometimes, it’s kind of painful to watch.

When I read about the Deadball Era, the way that everything was based on putting the ball in play, baserunners, fielders, that competition. It wasn’t just about the pitcher versus the hitter. It also was the hitter versus the defense and the baserunner versus the fielders. It was all of the unique elements of strategy and the illegal pitches and the fact that there were only one or two umpires and you could get away with all this little trickery and skipping bases and things like that. To me, it’s fascinating. I’m smiling right now just thinking about it. It’s a beautiful thing.

When I look at the players of the Deadball Era, there are maybe one or two I admire as human beings. Most of them, I don’t. Most are pretty much ordinary people who had extraordinary skills in this one area. I admire what they were able to do as baseball players. As a baseball fan and as a baseball historian, that’s something that I care about. The fact that they aligned themselves with a racist system of playing baseball where Blacks wouldn’t be allowed to play is horrible. But it doesn’t change the fact that these games occurred, that there was something beautiful in them, and that this thing of beauty deserves to be remembered. And it deserves to be remembered equally for the white players in their leagues — in the American and National Leagues — as it deserves to be remembered for the Black players as well.

Q: You mentioned wanting to go back and see Ty Cobb play. It was an era of personalities too. Which other players from the Deadball Era would you like to go back and see play in their time? The players then had different shapes, sizes, and quirks in ways that we don’t see as often today either.

A: If you look at the parts of the chapters of Deadball Stars of the American League and Deadball Stars of the National League which I wrote, I tended to want to write about the unsavory characters, like the guys who were throwing games. The two players that I was most fond of that I wrote about were Heinie Zimmerman and Benny Kauff, both of whom, at one time or another, were involved in some very shady dealings.

A: If you look at the parts of the chapters of Deadball Stars of the American League and Deadball Stars of the National League which I wrote, I tended to want to write about the unsavory characters, like the guys who were throwing games. The two players that I was most fond of that I wrote about were Heinie Zimmerman and Benny Kauff, both of whom, at one time or another, were involved in some very shady dealings.

One player I’d really like to see is Hal Chase, for two reasons. One is that the way people talk about his defense, you would think that he was the greatest player. In the 1920s, Lou Gehrig is hitting 45 home runs a year and driving in 170 runs, and articles from that period still suggest that Hal Chase was better. Then you look at Hal Chase’s numbers, and it’s like: ‘how is that even possible?’ Hal Chase is nowhere in the same galaxy as Lou Gehrig as far as offensive contributions are concerned, but then you hear these interviews where they talk about Chase’s defense, I want to see it. I want to see Chase’s defense because it seems like it must have been really incredible. I also want to see what it looked like when he was throwing games. I’ll be honest, I want to see what that looked like.

I think it’s fascinating that you had these athletes who basically were going around losing games on purpose. I would love to see what that looked like and how good they were at hiding it. Wouldn’t it be something to go back and watch the 1919 World Series and say: ‘can I tell that that Joe Jackson is not on the up-and-up or that Happy Felsch is not on the up-and-up’? I’d like to see a lot of those things.

I’d also like to see the power hitters of the Deadball Era. I’d really like to see Gavvy Cravath to see what his batting approach looked like. Would he swing for the fences? Were home runs just coming occasionally because of his power? Harry Davis also. There are a few of them. There was really no one who could survive in the Deadball Era as a home run hitter. But, nonetheless, we know that there were hitters before Babe Ruth who were swinging from their heels, and I would like to see what that looked like. There are also the characters we wrote about in the Deadball Stars book. There’s so many that jump to my mind.

I was always particularly fond of Dode Paskert. Tom Simon and I were just starting the Deadball Era Committee, and there were others as well who were involved. We were talking about how we didn’t all want it to be about Ty Cobb and Honus Wagner and Walter Johnson. We wanted it to be about the other guys, the people that you look at and go ‘huh, I wonder what that guy was like.’

I researched every fact I could possibly find about Dode Paskert. I found out that he was a great defensive center fielder. One thing I never found the exact answer to was why he was called ‘Dode.’ There were theories. I was looking up slang dictionaries from the early 20th century. Where did ‘Dode’ come from? What does it mean? There was one person who said it meant ‘stupid.’ That was one theory. Another theory is it had something to do with ‘dead.’ He had some particularly interesting things that happened in his life. He accidentally killed a kid with his car in Cleveland, where he was from, and he actually saved a whole family during his career with the Chicago Cubs, after he left the Phillies. He saved a whole family from a burning building. He had an interesting life.

Paskert seemed like he was one of those players who was really good but never great. In some ways, he was indicative of that whole ‘inside game’ approach of the Deadball Era, where you play great defense, you run the bases, bunt, hit and run. He had all that in his game. Nobody ever wrote a book about him. He wasn’t that good, but I always just thought: ‘I’d like to see that.’ I’d like to see what a really good but not great baseball player looks like in the Deadball Era. How does he play the game? He’s not going to be remembered. He’s not going to be the famous person from this era, but, nonetheless, Paskert had a long, successful career. I wanted to be able to picture in my mind what it was like to watch him play baseball. That, to me, always was the joy of the Deadball Era, being able to get into the weeds of players. Amos Strunk is another. Players who were good but haven’t been remembered because they weren’t good enough but nevertheless contributed something to baseball in that era.

Q: You mentioned that baseball of that period has some beauty to it. But are you also drawn to the rogues who brawled and were coarse?

A: I love brawls. I love ‘em. I love them today because it shows you the passion and just the contempt that players gain for each other. Like today, somebody hits a home run and they’ll admire it too long and next time they come up, the pitcher throws at them and they don’t like it and the batter charges the mound. In the Deadball Era, that passion for the game, that sort of conflict which is inherent to baseball was allowed to flourish more than it is today. Now, you have to watch more video replays of the brawls, safety is always a big concern, and so on and so forth. It wasn’t back then. Maybe that’s part of the charm of the Deadball Era, I don’t know. Life was viewed differently in that time. It wasn’t a society where everybody who went on their bike wore a bike helmet. It was a society in which people took more risks. People were willing to get in more fights.

A lot of these guys who came to the Major Leagues in the Deadball Era came from the mines, the factories, the mills. They came from the working class. They came from, in some cases, below the working class, what a Marxist would call the Lumpenproletariat. A lot of them are immigrants, many them from Germany and Eastern Europe. Baseball was also played by a different stratum of society back then. Today, a lot of the guys who get to the Major Leagues are the sons of Major Leaguers. They are people who come mainly from suburban upper-middle class backgrounds where their parents can afford to get them training year-round, and they can get all the equipment they need. Back then, baseball was just something you played in the street. It was an everyday activity that it’s not really today. So that’s another thing about the Deadball Era that I love, that this game was coming out of something that ordinary people really played all the time. I think that’s a beautiful thing.

Q: Should baseball remove Kenesaw Mountain Landis’ name from the Most Valuable Player Trophy? Should certain players be removed from the Hall of Fame because of their racial views? Does the Deadball Era deserve an asterisk since it was segregated? In general, what remedies would you propose to solve these problems relating to the Deadball Era?

A: Just me, personally, I would never take anyone out of the Hall of Fame. I think that once you’re a Hall of Famer, you’re a Hall of Famer, I don’t care what you do the rest of your life or what we find out about you later. I think it would set a horrible precedent to take someone out of the Hall of Fame. I would never do that under any circumstances. Even though, I don’t think, for instance, Tom Yawkey (note: a post-Deadball Era example), just on his contributions to baseball, I don’t think he’s a Hall of Famer. But he is. He was put there. And, to me, getting into the Hall of Fame is kind of like becoming a saint in the Catholic Church. Like, you’re just there now. That’s just how it is. So I would be strongly opposed to taking anyone out of the Hall of Fame for any reason.

I’m not in favor of asterisks. I think we, as human beings, can provide context for understanding statistics and records. I don’t think we ever need an asterisk for anything, any record, whether it’s steroids, Roger Maris. Nope, no asterisks. Really, the question I think we’re trying to answer here is how do we make baseball a racially-equitable place. That’s really the question — how do we make a better society? How do we improve as a society? Taking Tom Yawkey out of the Hall of Fame doesn’t do that. Putting asterisks on Ty Cobb’s batting averages doesn’t do that. So I’m against all of that. I think that’s all just meaningless symbolism that people would try to do to get people to stop talking about something. So, no.

I do think, though, that we can have a discussion about what we name after who. I think it is reasonable to look at Kenesaw Mountain Landis and say that he wasn’t just a person who existed during this time period. He was a person who was responsible for enforcing racial segregation in baseball so maybe we shouldn’t have an award named after him anymore. It doesn’t mean we take Landis out of the Hall of Fame. It doesn’t mean we stop studying who he was or what he did. Maybe we change the name of the award. I’m okay with that. I have no problem with that because I think there’s a difference between remembering history and supporting mythology.

When we reconsider Confederate statues, we’re not going to stop studying the Confederacy simply because we’re removing these statues. What we’re saying is that we no longer want these individuals to be the people that we literally put on a pedestal. We don’t want that anymore because we’re embracing a mythology about the Civil War that has been harmful to African-Americans. So in that case, yeah, bring down the statues. I’m fine with that. But it doesn’t mean we stop studying the Confederacy. It doesn’t mean we stop thinking about these issues. Landis is the same thing. I would be fine with changing the name of that award because I think Landis had a major role to play in the segregation of baseball.

Q: Are there any other changes you would make relative to the Deadball Era in a racial context?

A: I think more than taking things away, it’s about bringing things in. If there was a way for Major League Baseball to honor more Negro League players, I would be for it. You could have Major League Baseball say ‘You know what? The Negro Leagues were a major league. So, as a major league, we are going to document their records as part of the history of Major League Baseball. I think that would be good. I would be in favor of that. I think that we need to stop pretending that Negro League baseball was like a tragedy, that African-American players should have had the chance to play in the Major Leagues, and because they didn’t, therefore their careers did not have any meaning. I think we should start looking at the Negro Leagues from the perspective that they were part of the history of baseball and these things need to be remembered. And so I think that’s one major thing that baseball could do.

The Cy Young Award has such a nice sound to it. It has become such a part of the lexicon of baseball that you probably can’t change the name. But maybe baseball could create an award for Satchel Paige too. Maybe create an award for Rube Foster. With Landis, I can see the argument for removing his name from an award. It’s not a priority for me. I wouldn’t say that that’s the hill I’m going to die on. I don’t think it’s that important, honestly. I think it’s more about what can we do to acknowledge the contributions of Black people to the history of Major League Baseball.

Q: If someone had not been familiar with Deadball Era baseball, what would you like them to know about it?

A: There is so much that comes to mind. We were in the very early days of the Deadball Era Committee. Tom Simon, and I can’t remember who else, came up with this phrase about the baseball itself: Let’s get this lumpy licorice-stained ball rolling. The thing I’d first want them to know is about the actual baseball. I would want them to know first of all is what pitchers used to do to that poor baseball and how it was used compared to now, where the baseball is like this object which must never be made dirty in any way. Now, if a small speck gets on it, it gets thrown out. Back then, they were going to use one, maybe two the entire game. They were going to let people rub all kinds of foreign substances on it. Pitchers were going to darken it. The ball was going to be lumpy. It was going to fall apart sometimes, and that’s one of the reasons it wasn’t going to travel very far. I think you start with the baseball and what people used to do with it. So the one thing I would want them to know is what a Deadball Era baseball in the hands of a pitcher looked like. There’s probably like some bacteria growing on it, you know. It’s definitely not a socially distanced baseball. It’s not hygienic.

Q: It’s odd to me that baseball has been so strict with other things — like with penalties for gambling — but not strict with the baseball. Why?

A: It’s the culture of the game. It’s hard to explain sometimes. Baseball players and fans are often neurotic about some things. That’s part of the beauty of it, honestly. In the Deadball Era, they were laissez-faire about a lot. Another thing I hate about today’s game is instant replay. That we have to like forensically review every play, like we have to slow down every stolen base attempt to see ‘did his foot slide off the bag for this millisecond while the tip of the glove was touching it?’

What I wish I could say to people who care about stuff like that is ‘we’re playing a baseball game. We’re playing a game.’ It’s not supposed to be perfect. You don’t need to get the exact right answer to everything. Sometimes, we can have an approximation. Somebody might be upset with that, and that’s great because that’s part of the culture of the game is people getting upset with things that umpires decide. Now, it’s like we’ve somehow been able to get that out of the game, and it’s just sad to me. The more that we try to make baseball perfect, in the worst sense of that word ‘perfect,’ the more I want to go back to the Deadball Era.

Q: How would you reflect on Deadball Era baseball having been away from the Committee for more than a decade?

A: I left the Deadball Era Committee thirteen years ago because my life and my career were going in a different direction. I knew that I was going to be living overseas for a little while, and I just knew that I wasn’t going to be able to devote the same time to it. But the further I have gotten away from my time with the Deadball Era Committee and my time running the Committee, the more I’ve really come to miss it.

I would say that I’m grateful as well for you and everyone else on the Committee who has carried on the work all these years. It really means a lot to me personally as someone who was there at the founding of the Committee that the Committee had — and has — stewards that have taken such good care of it and that it continues to be out there and that people continue to care about the Deadball Era is moving to me. The fact that you even asked me to talk about of these issues, I was so happy that you did because it allowed me to re-engage with all these questions that I still really care about. So I just wanted to thank you for the opportunity.