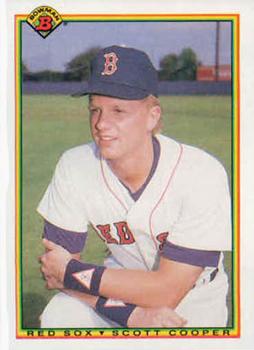

Scott Cooper

Scott Cooper was born the day after the St. Louis Cardinals beat the Boston Red Sox in Game Seven of the 1967 World Series. In 1986 he was drafted by the Red Sox and was a two-time All-Star for them. Prior to the 1995 season he was traded to the Cardinals where he played for a year, followed by seasons with the Seibu Lions in 1996 and Kansas City Royals in 1997. After playing in parts of seven major-league seasons — almost always at third base — he compiled a .265 career batting average and had driven in 211 runs. Cooper batted left but threw right-handed. He was listed at 6-feet-3 and 200 pounds.

Scott Cooper was born the day after the St. Louis Cardinals beat the Boston Red Sox in Game Seven of the 1967 World Series. In 1986 he was drafted by the Red Sox and was a two-time All-Star for them. Prior to the 1995 season he was traded to the Cardinals where he played for a year, followed by seasons with the Seibu Lions in 1996 and Kansas City Royals in 1997. After playing in parts of seven major-league seasons — almost always at third base — he compiled a .265 career batting average and had driven in 211 runs. Cooper batted left but threw right-handed. He was listed at 6-feet-3 and 200 pounds.

Scott Kendrick Cooper was born in St. Louis on October 13, 1967. His parents were Rick and Kathy Cooper. Rick Cooper (given name Kendrick) exemplified the American dream in some ways. As Scott put it in a November 2012 interview, “He started off as a trashman and worked his way up.”1 He worked in the waste disposal industry, becoming district sales manager for BFI, working more on the commercial side of things, with the bigger containers, and finally starting his own firm specializing in hazardous waste — R. Cooper Contracting Services Inc. of St. Charles, Missouri, founded in 1991.

“I remember he used to come home and get off the trash truck, coming in and me sitting there with a ball and two gloves — one for him and one for me. And he never said, ‘No.’ No matter how tired he was — and I know he was dead tired — but he always took the time.”

Kathy Cooper was a homemaker, helping raise Scott — her eldest child — and Scott’s brothers Shawn and Ricky, and their sister Nicky. “But when he [Rick] started his own company, she basically ran it for him — did all the admin and all that stuff’ working out of the home.

The family were athletic. Rick Cooper had scholarship offers as a football player — a safety — but when Scott was born, he had to go to work to support the family. Nicky was a dancer. Shawn and Ricky not only played baseball but also some football and basketball.

Scott’s high school team — Pattonville High School in St. Louis suburb Maryland Heights, Missouri — won the state championship in 1986 and Scott says that some of his best memories of baseball come from his high school days. In his junior year, Cooper was named “player of the year” in St. Louis, and was a two-way threat, batting .492 but also compiling a record of 8-1 as a pitcher. At the time he signed a letter of intent to join the University of Arkansas in April 1986, he was 3-0 (with a no-hitter) and batting .344. He had struck out 42 batters in 22 innings.2

He shelved plans for college when he was a third-round pick of the Red Sox in the June 1986 draft, signed by scout Don Lenhardt, and was assigned to the short-season Elmira Pioneers in the New York-Penn League. He batted .288 and drove in 43 runs in the 51 games he played.

Given his success pitching in high school, how is it that he didn’t pursue pitching in pro ball? “It was really close,” he explained. “We didn’t know if I was going to hit or pitch after high school. I signed a letter of intent to play football and baseball at the University of Arkansas. They were one of the schools that were going to let me play both sports, and they were going to let me pitch and play third. And then I got drafted. The Dodgers were the next pick after the Red Sox, I believe, and the Dodgers scout said afterwards, ‘If we were going to get you, we were going to make you a pitcher.’ That’s how close it was for pitching and me.”3

His 1987 season was in the Single-A South Atlantic League, playing 91 games at third base and 11 at first base for the Greensboro Hornets, appearing in 119 games in all, driving in 63 runs and hitting 15 home runs. He even pitched in two games — the only time in his pro career that he pitched. He worked a total of two innings, giving up two hits, two walks, responsible for one run, but striking out three. It was just mop-up work, he said, but he remembers teammate Curt Schilling telling him, “Man, what the heck are you doing? You throw 90-some miles an hour with a nasty curveball.”

Cooper’s 1988 season was again at Single A, this time for the Lynchburg Red Sox (Carolina League). In 130 games, he hit .298 and drove in 73 (with a .371 on-base percentage), scoring 90, and was named as the third baseman on the league’s All-Star team. Baseball America named him the second-best prospect in the Carolina League.4 To protect against another team claiming him in the December minor-league draft, he was added to Boston’s 40-man major-league roster.

Though it was a foregone conclusion he would be playing in the minor leagues, he was initially invited to spring training with the Boston ballclub. A promotion to Double A in 1989 saw Cooper playing in Connecticut for the Eastern League’s New Britain Red Sox under manager Butch Hobson. He played in 124 games, and hit .247 at the higher level, with 39 RBIs. Before, during, and after the season, a number of major-league clubs were reportedly inquiring about his availability in possible trades. The Red Sox, though, saw him as perhaps the “heir apparent to Wade Boggs.”5 He was seen as a “can’t-miss prospect.”6 When the season was over, though, the BritSox had finished in last place and Cooper’s performance perhaps resulted in some thoughts of trading him. If that were a possibility, the Red Sox apparently didn’t get a good enough offer.

In 1990, despite a lockout in spring training that saw him return home to St. Louis during what would normally have been the middle of spring training, Cooper did get his first taste of the big leagues later in the year.7 Before he was called up to the Boston team in September, he played for the Triple-A Pawtucket Red Sox. A strong start made him “attractive bait” for possible trades.8

In 124 games, he hit .266 with 12 homers and 44 runs batted in. At the very end of August, as Boston was making a run for the postseason, GM Lou Gorman of the Red Sox traded prospect Jeff Bagwell to the Houston Astros for pitcher Larry Andersen. Gorman felt freer to make the trade, knowing that Boston had an immediate need for pitching and that they had a solid prospect in Cooper.9 Bagwell became the National League Rookie of the Year in 1991 and league MVP in 1994, and later a Hall of Famer. It was a trade often decried by Red Sox fans, though one Gorman always defended.10

On September 5, during a Wednesday night game against visiting Oakland, the Red Sox were losing 10-0 after 8 ½ innings. Carlos Quintana was due to lead off the bottom of the ninth. He was 1-for-3 in the game, but Red Sox manager Joe Morgan had Cooper pinch-hit for Quintana. He was the first major-league batter that reliever Steve Chitren ever faced; Bob Welch had thrown the first eight innings for Oakland. On a 2-2 count, Cooper took a called third strike. In his debut, Chitren got Wade Boggs to fly out to center, walked Phil Plantier, and then got Danny Heep to fly out to right. Cooper’s debut was not as enjoyable a memory, but he had at least gotten his feet wet.

Cooper appeared in one more game in 1990, 11 days later against the White Sox at Comiskey Park. Again, it was in the ninth inning. Chicago was leading, 4-1, after eight. After two outs sandwiched around a Mike Greenwell single, first baseman Mike Marshall singled, too, and the Red Sox had runners on first and second. Morgan had Cooper pinch-run for Marshall. Tony Pena singled to right, scoring Greenwell. Cooper went first to third. Pena took second on the throw in. He was in scoring position, the potential tying run. Danny Heep walked, loading the bases, but Jody Reed made the third out on a line drive right back to the pitcher.

Cooper played for Pawtucket in 1991, under manager Butch Hobson, and was again a September callup, after a full season with the PawSox and after Pawtucket was eliminated from the playoffs. This time, in 1991, he played in 14 games. He got his first major-league base hit in the second game, at Yankee Stadium in the top of the eighth on September 12, though it wasn’t a spectacular one. It was a “roller [which] took a bad hop off the chest of rookie third baseman Mike Humphreys.”11 He was left stranded. He played third in the eighth and ninth innings. Of the hit, Cooper said, “I’ll take them all.”12

He might have been called up sooner, but with Wade Boggs a fixture at third base for Boston, the opening for Cooper was not clear. He was well aware of the success that Bagwell had enjoyed and wanted the opportunity to progress himself, even if it meant he had to be traded.13

On September 21, he had a two-hit game, against the Yankees at Fenway Park — both of them doubles. It took a while to get his first run batted in. That came in Boston against Detroit on October 3. With runners on second and third in the seventh inning, he singled off Bill Gullickson and drove in both baserunners. The score had been 4-0, Tigers, but now it was 4-2. Cooper himself scored three batters later. The score was 4-3, but the Tigers scored six runs in the top of the eighth. In the bottom of the eighth, he tripled and drove in Tom Brunansky with his third run of the game. Despite the three RBIs, the Tigers still prevailed, 10-5.

In the final two games of the season, Cooper drove in two runs in each. In the 35 at-bats he had in 1991, he hit .457 with a total of seven RBIs.

Cooper made the big-league team in 1992 and, though Wade Boggs was the team’s primary third baseman, Boggs had a disappointing year, hitting just .259.14 Cooper had a bit of a rocky spring training, coming down with the flu and then a hamstring pull, but ultimately had a very strong season.15

Cooper hit .276, the highest batting average on the team, managed by Butch Hobson, who had been Cooper’s manager at New Britain in 1989 and at Pawtucket in 1991.16 Cooper had 33 RBIs in 379 plate appearances. He had an impact early on, leaving his work as a fill-in bullpen catcher and coming in to pinch-hit on April 19, driving in the final run of a bottom-of-the ninth, four-run rally to beat the Blue Jays, 5-4.17

He had played in 123 games, almost exactly half of them (62) at first base, where he compiled a .990 fielding percentage (only five errors in 484 chances.) He played in 47 games at third base (.970 fielding percentage). He also was the DH in two games and played one inning at second base and one inning at shortstop.

On July 4 at Chicago, Cooper ended the team’s nine-game road losing streak by driving in both runs — one in the second and one in the sixth — for a 2-1 Red Sox win. On August 30 in Anaheim, his bases-clearing double off the Angels’ Scott Bailes in the top of the 10 th gave Boston a 4-2 win. His first career home run didn’t come until his 112 th career game, in the second inning of the September 4 game in Oakland, off Dave Stewart, the first run in an 8-3 win.

The 1992 Red Sox finished in seventh place, last in the American League East and 23 games behind the first-place (and World Series champion) Toronto Blue Jays.

In 1993, Cooper played in almost every game — 156 of the 162 games the Red Sox played. The Red Sox elected not to offer arbitration to Wade Boggs, and he signed with the New York Yankees in December 1992, which opened up the third-base position for Cooper. He started off nicely, with five RBIs in his first three games, including a stretch of four consecutive RBI base hits, his last time up on April 7 and first three at-bats on April 8.

He made the most of the opportunity and, despite getting beaned on May 11 and hit on the right wrist by another pitch on May 25, he kept on playing. He was named the lone Red Sox representative to the 1993 All-Star Game.18 Both Cooper and Boggs played in the game; neither had a base hit. By the end of the season, Cooper had a .279 batting average and had driven in 63 runs, both statistics placing him in the middle of the pack on that year’s team. The Red Sox finished in fifth place, 15 games behind the Blue Jays. He needed to work on his fielding, and Hobson — a former third baseman — spent time hitting him groundballs.19 He committed 24 errors at the hot corner in 1993, resulting in a fielding percentage of .937.

Cooper was an All-Star again in 1994. The league split into three divisions and the Red Sox finished fourth in the AL East, 17 games behind the first-place Yankees. It was a season truncated by a player strike, and the Sox had only played 115 games when play was stopped in August. Individually, Cooper more than held his own. He played in 104 of the games, batting .282 (third on the team and also a personal best) and driving in 53 runs (second only to Mo Vaughn’s 82). He homered 13 times, a career best despite the team only playing in 70% of its scheduled games.

At Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium in the 1994 All-Star Game, the Yankees’ Boggs was the starting third baseman but Cooper took over after 5 ½ innings. A Marquis Grissom home run off Randy Johnson gave the NL a 5-4 lead in the bottom of the sixth, but Cooper doubled to left field in the top of the seventh off Danny Jackson, driving in Ivan Rodriguez and tying the score. Both he and Chuck Knoblauch scored when the next batter, Kenny Lofton, singled to left. The NL scored two in the bottom of the ninth and tied the score, then won in the 10 th, 8-7.

During the 1994 season, his most notable game was the five-RBI game on April 12 at Kansas City in which Cooper hit for the cycle. He was coming off a season-opening 2-for-19 stretch. Red Sox pitchers coughed up 11 runs, but Red Sox batters drove in twice as many and won the game, 22-11. Cooper’s two-run double off starter Kevin Appier provided the fifth and sixth runs of the first inning. A one-out solo home run off Appier in the top of the third upped the Red Sox lead to 8-1. Facing reliever Hipolito Pichardo, he tripled to left field; he was thrown out at the plate when going for an inside-the-park home run, but got credit for the triple nonetheless. At this point, all he lacked was the hit usually easiest to obtain — the single. He reached on an error by the third baseman in the top of the sixth; a run came in on the play, part of an eight-run inning. In the seventh, he drove in two more runs on another double, but still the single eluded him. It finally came in the top of the ninth, a leadoff single right up the middle — hit off a position player, shortstop David Howard, who threw the last two innings and only gave up one run.20

One week later to the day, at Fenway Park, Cooper hit a third-inning grand slam off Oakland’s Bob Welch, the four RBIs giving Boston a 7-0 lead in a game they won, 13-5. The next day, Boston won, 2-0, Cooper’s sacrifice fly driving in the first run. And on April 24, his leadoff homer in the bottom of the sixth provided the final run in a 5-4 win over the visiting Angels. Capping off quite a month, he drove in all four runs in a 4-1 win in Oakland on April 28 with a two-run double in the third and a two-run homer in the sixth.

The very next day, his two-run homer provided the winning margin over the Angels, 6-4.

Cooper had seven homers and 23 RBIs by the end of April and was batting .342. He added 10 RBIs in May, half of them in games the team lost. He had 14 RBIs in June, but in July he only drove in four. The last game the Red Sox played in 1994 was on August 10, after which the strike began.21 Cooper’s last game had been a week earlier, on August 3. He had suffered torn cartilage in his right shoulder that had affected him for a month. Red Sox doctor Arthur Pappas thought he might have injured the shoulder when diving for a ball back in early July.22 That would help explain his lack of production that month. Cooper had surgery on August 23 at University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester, Massachusetts. Oddly, Dr. Pappas also performed surgery on outfielder Mike Greenwell for almost exactly the same thing, and on the same day.23

Cooper didn’t play for Boston in 1995; he was traded a few days after the 1995 season began, sent to the St. Louis Cardinals on April 9 as part of a four-player trade.24

The season started late, and the Cardinals played 143 games, Cooper appearing in 118 of them, all at third base. He’d hit for an overall .284 in his time with the Red Sox but, after a strong start to the season, wound up hitting only .230 for his hometown Cardinals. He could hardly have had a better debut than on Opening Night, April 26. Though he struck out his first time up, he hit an RBI double, a single, a lineout, and then — in the bottom of the ninth — a two-run single boosting the Cards to a 7-6 walkoff win over the visiting Phillies. He had driven in four of the runs. And he had done it in a Cardinals uniform, the team he had rooted for while growing up.25 There were other games he helped win, driving in the winning runs on May 6 against Houston, but his two biggest RBI games were back-to-back losses to the Cubs on July 1 and 2. Cooper drove in five runs in the first of those games, and four in the second.

Saddled with a persistent hamstring problem, his average crept downwards to the aforementioned .230. He drove in 40 runs, fifth-best on the fourth-place team, but it was a disappointing year. Defensively it was a tale of two halves; he committed 15 errors before the All-Star break but only three afterward.

He became a free agent after the season and was unable to find a team that was sufficiently interested. Instead, he went overseas and played his 1996 season for the Seibu Lions in the Japan Pacific League for a figure reported as more than $2,000,000.26 It was far more than major-league clubs were going to offer. He appeared in 81 games of the team’s 126 games and was released near the end of September. He had hit .243 with 27 RBIs, neither stat placing him in the top six on the Lions. “Going to Japan was an interesting experience,” he said. “I learned a lot and was paid well, but I’m really glad to be back. With the pitching you see very day — they can really paint — it can be a struggle over there.”27

In December 1996, Cooper signed a one-year, minor-league contract with the Kansas City Royals, making the major-league team in spring training. Though he appeared in 75 games during 1997, he only played 39 at third base (often as a late-inning defensive replacement), in addition to eight games at first base and five as DH. He entered 31 games as a pinch-hitter. He hit for a .201 batting average, with three homers and 15 runs batted in. His season highlight was the walkoff single he hit on July 14 in the bottom of the 14 th inning, for a 2-1 win over the Milwaukee Brewers, which broke a 12-game Kansas City losing streak. He was out from July 23 to September 1 with a left hamstring tear. The bases-loaded triple in the bottom of the eighth on September 9 was another memorable hit, but the Royals already the game reasonably well in hand, 7-3. Cooper’s single made it 10-3.

After the season, he became a free agent again. He had enough time in big-league ball that the minimum salary, given his tenure, scared off possible suitors. He did sign a minor-league contract with the Texas Rangers but didn’t make the team in spring training. The now-recurrent hamstring problem hampered him. It had cropped up again. He thought about trying another comeback after a year off but spent the next couple of years relaxing — hunting, fishing, and thinking about the next chapter of his life.

A friend was the assistant athletic director at Fontbonne University in Clayton, Missouri. Cooper became the head coach of the baseball team and held that position for five years, including being named coach of the year for the St. Louis Intercollegiate Athletic Conference in 2003.

“I did that for five years,” he said. “I had a great time doing that. Learned a lot. Had some great kids. From there, I got on the instruction side of it and that’s still what I do today.” In 2005, he was part-owner of a baseball training facility in the St. Louis area. Starting in 2007, he became part of a non-profit organization called the St. Louis Gamers. The program works with young players from ages 10-18.28

He works with another former major leaguer, Matt Whiteside. “I just wanted a place to be able to teach. What I do now is I help with my Legion baseball team. I give lessons. I do a bunch of different things for the Cardinals, as far as clinics, camps, all that kind of stuff. All in the St. Louis area.”

Divorced, Cooper shares parenting of two sons, Camden — age 13 — and Chase, age 12 at the time of a late-2021 interview.

Having grown up and remaining in the St. Louis area, but having spent most of his professional career with the Red Sox, was there a team he rooted for in the 2004 World Series? “I was a big Cardinals fan. Big Red Sox fan. But, you know, as the Red Sox were making that run, it was tough for me. I was basically raised in New England — New Britain, Pawtucket, and Boston. I went through ages 18 through 28 there, as a kid growing into a man. And with that magical run they were making, it was tough not to pull for them. And Schilling was one of my first roommates. We spent a lot of time together on the bus in Elmira, New York, that summer trying to figure it all out. I was kinda pulling for him, too.”

Asked about his favorite baseball memories, hitting his first homer, hitting the grand slam off Bob Welch, and hitting for the cycle were big memories, of course. But there were two more personal moments that stood out.

“I remember my first call-up. I remember being on the top step. Getting ready to play the Yankees and I’m getting ready to put my cap over my chest and I hear, ‘Hey, kid. Remember this first National Anthem. You’ll never forget it . . . You made it!’ That was Roger Clemens.”

Cooper had been a big Jack Clark fan — as was almost every kid in St. Louis in 1985 when Clark hit a three-run, ninth-inning homer off Tom Niedenfuer to win the pennant for the Cardinals over the Dodgers in Game Six of that year’s NLCS. “It was Jack Clark for President, here in St. Louis,” he recalls. “Fast forward five years and I’m in Boston. I go into the clubhouse and see my name in the lineup. Before I can even see who’s hitting after me, I hear, ‘Hey, kid. I need you to get on base. I’ve got an RBI incentive clause in my contract.’ It’s Jack Clark.”

In his instructional work, Cooper doesn’t work with pitchers. He does, of course, work with infielders on their throwing. “Really, anything that has to do with baseball. I do a lot of talks to college and high school kids about the mental side of hitting. Everybody asks, ‘Hey, what is your favorite thing to teach? Or favorite age group? You know, I teach some kids who come in here that can hardly hold onto a bat. I get as much satisfaction out of teaching them how to hit, to make contact, as I do to teaching somebody how to hit a nasty curveball in college. It’s all relative and I feel really fortunate, really blessed to be able to do that and communicate that, and be passionate about it, and to be able to pay some bills at home with it.”

Last revised: February 11, 2022

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Joel Barnhart and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, SABR.org, and the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball.

Notes

1 Author interview with Scott Cooper on November 19, 2021. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations from Scott Cooper come from this interview.

2 “Arkansas,” Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee), April 24, 1986: 37.

3 When Cooper went over to scout Don Lenhardt’s house to sign with the Red Sox, he says that Lenhardt told him they loved his arm but wanted him to concentrate on hitting. After his first few years in the minors, if the hitting didn’t evolve, he’d still be only 21 or 22 and there would be time to work on pitching. If he tried pitching first, he might blow out his arm and then be done, but “it was very close, very close in terms of what the scouts thought.” Cooper interview November 2021.

4 Joe Giuliotti, “Morgan: LaRussa deserved honor,” Boston Herald, October 30, 1988: B7

5 Owen Canfield, “Musical chairs in the minors,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1989: F1C.

6 Adrian Wojnarowski, “Cooper powers Britsox,” Hartford Courant, June 24, 1989: B22.

7 On his return home and his thoughts at the time, see Nick Cafardo, “Cooper opts to head home,” Boston Globe, March 13, 1990: 65.

8 Nick Cafardo, “Cooper becomes attractive bait,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1990: 53.

9 Stephen Harris, “Reliever Andersen a costly acquisition,” Boston Herald, September 1, 1990: 8.

10 See, for instance, Gordon Edes, “Gorman defends trade,” Boston Globe, June 13, 2003: 87.

11 Mike Shalin, “Injuries mount for Sox,” Boston Herald, September 13, 1991: 90.

12 Shalin, “Injuries mount for Sox.”

13 Mike Shalin, “Ready to fly Red Sox’ Coop?” Boston Herald, December 8, 1991: 14.

14 One of the reasons the Red Sox kept Cooper was that they couldn’t send him down to the minors without his approval. Sean Horgan, “Red Sox, a major change?” Hartford Courant, February 23, 1992: D1B.

15 For the problems in spring training, see Sean Horgan, “He’s part of the plan, but unexpected hurts Cooper,” Hartford Courant, April 2, 1992: C3.

16 His .2759643 edged center fielder Bob Zupcic’s .2755102. Boggs played the lion’s share of the games at third base and Mo Vaughn did so at first base, but Cooper filled in — sometimes in the later innings — and only five players on the team appeared in more games.

17 Third-base coach Don Zimmer was recovering from knee surgery, so usual bullpen catcher Gary Allenson took over coaching at third base. Cooper helped by catching in the bullpen. When he came in to pinch-hit, he banged an RBI single off the pitcher’s rubber and won the game. See “Red Sox get bullpen (hitting) relief,” Chicago Tribune, April 20, 1992: Section 3:7. The ball “ricocheted high into the air” and Cooper “beat the throw by sliding safely into first — head-first.” Michael Vega, “Turning the jeers to cheers,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1992: 41.

18 He thought Butch Hobson might have been joking when the Red Sox manager first informed him. Larry Whiteside, “Cooper All-Star choice,” Boston Globe, July 9, 1993: 61.

19 Nick Cafardo, “Another pitcher on DL,” Boston Globe, July 1, 1993: 51. Cafardo wrote another article about Cooper’s work on his defense a year later. See “Sox’ Cooper is no longer on hot seat at hot corner,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1994: 83. By late July, he was named the best-fielding third baseman in the league in a Baseball America poll of managers. Nick Cafardo, “Red Sox get down, then upend Yankees,” Boston Globe, July 27, 1994: 77.

20 He said he’d never hit for the cycle before, even in Little League. Nick Cafardo, “Red Sox fire 22-caliber shot,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1994: 61. Recalling the moment in the 2012 interview, Cooper said, David Howard “threw me a nasty knuckleball, the first pitch. I stood there in the box and said, ‘What are you doing? You threw me a knuckleball?’ He said, “I’m trying to get you out, man.’ Then he tried to sneak a fastball by me and I almost took his head off on that one. That was a really, really cool night. Being in Kansas City, I had a bunch of people there, too.”

21 The team wasn’t deprived of any glory that year. The Red Sox finished fourth in the AL East, 17 games behind the New York Yankees.

22 Nick Cafardo, “Cooper has small tear in shoulder,” Boston Globe, August 6, 1994: 65.

23 Nick Cafardo, “Greenwell and Cooper have surgery,” Boston Globe, August 25, 1994: 60. Cafardo pointed out the unusual situation in that both players were on strike at the time, on strike against the Red Sox team of which Pappas was a co-owner.

24 Right-handed pitcher Cory Bailey was traded with Cooper for another pitcher, left-hander Rheal Cormier, and outfielder Mark Whiten.

25 Rick Hummel, “’Icing on Cake’ as Fans Adopt Hometown Hero,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April27, 1995: 1D.

26 “Sports Log,” Boston Globe, January 26, 1998: 70.

27 Peter Gammons, “Big trade a lesson in economics,” Boston Globe, March 30, 1997: 48.

28 St. Louis Gamers website: https://stlgamers.net/ accessed December 18, 2021.

Full Name

Scott Kendrick Cooper

Born

October 13, 1967 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.