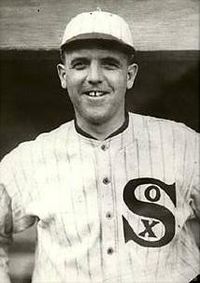

Eddie Cicotte

Though he didn’t invent the pitch, Eddie “Knuckles” Cicotte was perhaps the first major-league pitcher to master the knuckleball. According to one description, Cicotte gripped the knuckler by holding the ball “on the three fingers of a closed hand, with his thumb and forefinger to guide it, throwing it with an overhand motion, and sending it from his hand as one would snap a whip. The ball acts like a ‘spitter,’ but is a new-fangled thing.”1

Though he didn’t invent the pitch, Eddie “Knuckles” Cicotte was perhaps the first major-league pitcher to master the knuckleball. According to one description, Cicotte gripped the knuckler by holding the ball “on the three fingers of a closed hand, with his thumb and forefinger to guide it, throwing it with an overhand motion, and sending it from his hand as one would snap a whip. The ball acts like a ‘spitter,’ but is a new-fangled thing.”1

Cicotte once estimated that 75 percent of the pitches he threw were knuckleballs. The rest of the time the right-hander relied on a fadeaway, slider, screwball, spitter, emery ball, shine ball, and a pitch he called the “sailor,” a rising fastball that “would sail much in the same manner of a flat stone thrown by a small boy.”2 Whether he was sailing or sinking the ball, shining it or darkening it, the 5-foot-9, 175-pound Cicotte had more pitches than a traveling salesman. “Perhaps no pitcher in the world has such a varied assortment of wares in his repertory as Cicotte,” The Sporting News observed in 1918. “He throws with effect practically every kind of ball known to pitching science.”3

But the most famous pitch Cicotte ever threw was the one that nailed Cincinnati Reds leadoff man Morrie Rath squarely in the back to lead off the 1919 World Series, a pitch that signaled to the gamblers that the fix was on. After confessing to his role in the scandal one year later, Cicotte was banned from the game for life, a punishment that perhaps denied the 209-game-winner a spot in the Hall of Fame.

- Learn more: Click here to view SABR’s Eight Myths Out project on common misconceptions about the Black Sox Scandal

Edgar Victor Cicotte (pronounced SEE-cot)4 was born on June 19, 1884, in Springwells, Michigan, a former township in the Detroit metropolitan area, into a family of French heritage. He was the son of Ambrose and Archangel (Drouillard) Cicotte. Eddie’s brother, Alva, was the grandfather of Al Cicotte, who pitched in the major leagues for five seasons from 1957 to 1962. By the time Eddie was 16 years old, his father had died, forcing his mother to support her large family as a dressmaker. Leaving school early, Eddie took up work as a boxmaker to help pay the family bills.

Cicotte began his baseball career, according to some sources, as early as 1903, playing semipro ball in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. In 1904 he pitched for Calumet (Michigan) and Sault Ste. Marie (Ontario) in the Northern Copper League, posting a record of 38-4 with 11 shutouts.5 Based on that dominating performance, Cicotte earned a tryout with the Detroit Tigers in the spring of 1905. The Tigers determined that he wasn’t ready for the majors, and optioned him to Augusta (Georgia) of the South Atlantic League, where he compiled a record of 15 wins against 9 losses, and brawled with his young teammate Ty Cobb after a Cobb stunt cost Cicotte a shutout. As a joke Cobb had taken popcorn with him to his position in center field and as a result committed an error that led to a run.6 This incident notwithstanding, among his teammates Cicotte was known as an easygoing prankster who enjoyed a good laugh.

Near the end of the season Detroit brought Cicotte up and he made his major-league debut on September 3, 1905, allowing one run in relief and getting tagged with the loss in a 10-inning game. Two days later Cicotte earned his first major-league win, a complete-game victory over the Chicago White Sox. He finished the year 1-1 with a 3.50 ERA, but would not return to the major leagues for another three seasons.

Cicotte began 1906 with Indianapolis of the American Association, where he posted a 1-4 record in 72 innings before landing with Des Moines of the Western League. Cicotte blossomed with his new team, registering an 18-9 record. The following season he pitched for Lincoln, also of the Western League, going 21-14. Impressed by the young hurler’s arsenal of pitches, the Boston Red Sox purchased Cicotte’s contract for $2,500 at the end of the 1907 season.

During his five-year stint with the Red Sox, Cicotte lost nearly as many games as he won, and frequently found himself in trouble with Red Sox owner John I. Taylor, who accused the pitcher of underachieving. “He was suspended without pay so much of the time that it was like having no job,” the Chicago Tribune’s Sam Weller wrote of Cicotte’s Boston career.7 On a club that consistently failed to meet expectations, Cicotte often became the scapegoat, and in 1911 Taylor tried to secure waivers on his inconsistent pitcher, only to pull back when another team made a claim. “[Taylor] wouldn’t like the way I was working, or perhaps the opposition had made one or two hits,” Cicotte later charged. “Taylor never liked me; I never liked him, and it was seldom that I went through a game without having him comment upon it.”8

After Cicotte started the 1912 season with a 1-3 record and a 5.67 ERA in six starts, the Red Sox, though no longer owned by Taylor, had finally seen enough. On July 22 the team sold Cicotte’s contract to the Chicago White Sox, where the 28-year-old right-hander began to mature into one of the game’s best pitchers. With Boston, Cicotte had won 52 games and lost 46. Over the next 8½ seasons with the White Sox, he won 156 games against 101 losses.

The biggest reason for this improvement was Cicotte’s gradual mastery of his expansive pitching repertoire. As his command over his knuckleball improved, Cicotte’s walk rate dramatically decreased; from 1912 to 1920 he ranked among the league’s 10 best in fewest walks per nine innings seven times, leading the league in 1918 and 1919, when he walked 89 in 572⅔ innings.

Cicotte also fully exploited the era’s liberal regulations regarding the doctoring of the ball. In this area, his most infamous pitch was the shine ball, in which he rubbed one side of the ball against the pocket of his right trouser leg, which had been filled with talcum powder.

Flustered opponents protested to American League President Ban Johnson that the pitch should be outlawed, but Johnson ruled the pitch legal in 1917, and it would remain so until February 1920. Thanks to the knuckleball, the shine ball, the emery ball (ruled illegal by Johnson in early 1915), and other trick pitches, Cicotte struck out a fair number of batters, placing in the top 10 in strikeouts per nine innings three times, even though his fastball probably couldn’t break a plane of glass. Asked to explain his success, Cicotte chalked it up to “head work,” adding, “It involves an ability to adapt pitching to certain conditions when they arise and perhaps use altogether different methods in the very next inning.”9

In 1913 Cicotte enjoyed his first standout season in the major leagues, posting an 18-11 record to go along with a 1.58 ERA, second best in the American League. That offseason, Pittsburgh of the newly formed Federal League attempted to sign Cicotte, but White Sox owner Charles Comiskey was able to secure the pitcher’s loyalty through a three-year contract. In the first year of his contract, Eddie managed only an 11-16 record, although his 2.04 ERA was fifth best in the league. After a mediocre 13-12 campaign in 1915, Cicotte finally hit his stride in 1916, when he split time between the starting rotation and bullpen, posted a 1.78 ERA, won 15 out of 22 decisions, and had what today would be five saves. (The statistic hadn’t been invented yet.)

The following year, 1917, Cicotte moved back to the starting rotation and enjoyed the best season of his career, as the White Sox captured their first pennant in 11 seasons. Cicotte led the way, ranking first in the league in wins (28), ERA (1.53), and innings pitched (346⅔). Eddie also tossed seven shutouts, including a no-hitter against the St. Louis Browns on April 14, the first of six no-hitters pitched in the major leagues that season. In that year’s World Series, Cicotte contributed one win to Chicago’s six-game triumph over the New York Giants. He was, according to Grantland Rice, “the most feared pitcher of the series.”10

After Cicotte’s breakthrough season, Comiskey offered his star pitcher a $5,000 contract, with a $2,000 signing bonus, making him one of the highest compensated pitchers in baseball.11 But Cicotte failed to produce an encore suitable to his dominant 1917 campaign, as he wrenched his ankle in early May, and limped his way through the season to a mediocre 2.77 ERA and 19 losses, tied for the most in the league. It was not a performance to inspire Comiskey to hand out a raise, and when the 1919 season began, financial troubles were weighing heavily on Cicotte. According to the 1920 Census, Cicotte was the head of household for a family of 12, including his wife, Rose; their three children; his wife’s parents; Eddie’s brother and wife; and a brother-in-law and his wife and child. To make room for his large family, Cicotte took out a $4,000 mortgage on a Michigan farm.12

Cicotte regained his 1917 form, pitching the White Sox to their second pennant in three years. Once again, Eddie led the American League in victories (29) and innings pitched (306⅔, tied with Jim Shaw). His 29-7 record was good enough to lead the league in winning percentage (.806), and his 1.82 ERA ranked second. In early September, first baseman Chick Gandil and infielder Fred McMullin approached Cicotte about throwing the World Series. After thinking it over, Eddie agreed to the scheme, telling Gandil privately, “I would not do anything like that for less than $10,000.” Three days before the Series began, Cicotte demanded to have the money in hand before the team left for Cincinnati. That night, he found $10,000 under his pillow.13

Contrary to conventional wisdom, Cicotte’s abysmal performance in the 1919 World Series was not a complete surprise to informed observers. Throughout September, reports surfaced that the overworked Cicotte was suffering from a sore shoulder. Prior to the first game of the Series, Christy Mathewson noted, Cicotte “has had less than a week [actually two days] to rest up for his first start. … And that may not prove to be enough. If he blows up for a single inning it may cost the White Sox the championship, for I think the first battle is going to have a very strong bearing on the outcome, especially if the Reds win it.”14

With at least six of his other teammates in on the fix, Cicotte led the way in blowing the first game, surrendering seven hits and six runs in 3⅔ innings of work, and fueling Cincinnati’s winning rally by throwing slowly to second base on what should have been an inning-ending double-play ball. The performance was so bad that it generated renewed speculation that Cicotte was suffering from a “dead arm.”

For his second start, in Game Four, with the White Sox trailing two games to one, Eddie pitched more effectively, holding the Reds to just five hits and two unearned runs, both coming in the fifth inning on two Cicotte errors, including one inexplicable play in which he muffed an attempt to cut off a throw from the outfield, allowing the ball to go to the backstop and letting a Cincinnati runner – who had already stopped at third – score. The miscues were enough to ensure that the White Sox lost the game, 2-0. Afterward, Chicago manager Kid Gleason declared, “They shouldn’t have scored on Cicotte in 40 innings. … There wasn’t any occasion for Cicotte to intercept that throw. He did it to prevent [Larry] Kopf from going to second. But Kopf had no more intention of going to second than I have of jumping in the lake.”15

Though Eddie had received his $10,000 before the start of the Series, many of his fellow conspirators had not received the money promised them by the gamblers, so before Cicotte’s third start, in Game Seven of the best-of-nine Series, the players decided to play the game to win. Accordingly, Cicotte put forth his best effort of the Series, allowing just one run on seven hits in a 4-1 Chicago victory. Lefty Williams threw the following game, however, giving Cincinnati the world championship. In the wake of Chicago’s defeat, Mathewson publicly tossed aside rumors that the Series had been fixed, saying, “No pitcher could guarantee to toss a game. … Even if a pitcher should let the other side get two or three runs before he was yanked, he could not guarantee that the other side wouldn’t come up the next inning and make four or five. That wipes out any single pitcher and leaves the proposition of fixing on a club. This can’t be done.”16

Despite the persistent rumors that swirled around the club that offseason, Cicotte re-signed with Chicago for 1920, and put forth another excellent season, posting a 21-10 record with a 3.26 ERA. That summer Babe Ruth electrified the sport with his 54 home runs for the New York Yankees, but Cicotte grabbed a few headlines of his own after he stymied Ruth in several encounters. Asked to explain his success, the crafty Cicotte allowed that he mixed up his pitches and relied heavily on the spitball, because the pitch was “hard to hit for a long clout.”17

Before the season, the spitball and other doctored pitches, including Cicotte’s famous shine ball, had been banned from baseball. Although a number of established spitball pitchers were given a one-year exemption from the rule, Cicotte was not one of them.

On September 27, 1920, the Philadelphia North American ran a story in which Billy Maharg, one of the gamblers in on the Series fix the previous fall, testified to his role in the affair, and specifically named Cicotte as the man who initiated the plot. The next day, Eddie met with White Sox counsel Alfred Austrian and admitted to his role in the scandal. He also implicated seven of his teammates.18 Afterward, he went to the Cook County Courthouse and repeated his story for a grand jury charged with investigating corruption in baseball. The grand jury responded to Cicotte’s testimony by indicting all eight of the “Black Sox” players for throwing the 1919 World Series.

In front of the grand jury, Cicotte testified that he began to have second thoughts during the Series. After losing Game One, he was “sick all night” in the hotel and told roommate Happy Felsch, “Happy, it will never be done again.” He also said that he tried his best to win Game Four, claiming “I didn’t care whether I got shot out there the next minute. I was going to win the ball game and the series.” But he never offered to return the gamblers’ money. “I couldn’t very well do that,” he admitted.19

Though he and the other seven accused players were acquitted of conspiracy charges the following year, Eddie Cicotte’s major-league baseball career ended with his confession. For the next three years he played with several of his banned teammates for outlaw teams in Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota, but by 1924 Cicotte had moved on with his life.20 He worked as a Michigan game warden and managed a service station before finding a job with the Ford Motor Company, where he remained until his retirement in 1944.

During the last 25 years of his life, Cicotte raised strawberries on a 5½-acre farm near Farmington, Michigan. In an interview with Detroit sportswriter Joe Falls in 1965 he said he lived his life quietly, answering letters from youngsters who sometimes asked about the scandal. He agreed that he had made mistakes, but insisted that he had tried to make up for it by living as clean a life as he could. “I admit I did wrong,” he said, “but I’ve paid for it the past 45 years.”21 Falls seemed to agree, noting that as he prepared to leave Cicotte’s home, he looked at Eddie’s socks. They were white.

Eddie Cicotte died on May 5, 1969, at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit. His death certificate listed his occupation as baseball player, Chicago White Sox. He was buried in Park View Cemetery in Livonia, Michigan.

An updated version of this biography appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). This biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006).

Sources

Asinof, Eliot, Eight Men Out (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1987).

Falls, Joe, Interview with Eddie Cicotte. Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1965.

Lardner, Ring, Chicago Examiner. July 21, 1912.

MacFarlane, Paul, ed., Daguerreotypes. The Sporting News, 1981.

Stump, Al, Cobb (New York: Algonquin Books, 1996).

findagrave.com.

Obituary, The Sporting News. May 24, 1969.

Michigan Death Certificate.

Obituary, New York Times. May 9, 1969.

1880 Wayne County, Michigan, Federal Census.

1920 Wayne County, Michigan, Federal Census.

1930 Wayne County, Michigan, Federal Census.

ancestry.com.

The Sporting News, February 23, 1933, 8.

retrosheet.org.

Contract card, National Baseball Library, Hall of Fame.

Washington Post, August 24, 1906; August 24, 1907; March 8, 1908; April 15, 1917.

New York Times, April 15, 1917.

Sporting Life, February 21, 1914.

Kermisch, Al, “From a Researcher’s Notebook.” Baseball Research Journal #23 (Cleveland: SABR, 1994.)

Chicago Daily Tribune, August 27, 1906.

baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Washington Post, March 8, 1908.

2 Ty Cobb, Memoirs of Twenty Years in Baseball (New York: Dover Publications, 2009), 65, 68.

3 The Sporting News, May 2, 1918.

4 The proper pronunciation of Eddie Cicotte’s name was cleared up during the Black Sox criminal trial in 1921: After multiple attorneys butchered his name in court, Cicotte reportedly told Judge Hugo Friend, “Would you please have it entered in the court record that my name is … pronounced See-kott, with the accent on the See?” See The (Chillicothe, Missouri) Daily Constitution, August 22, 1921.

5 Indianapolis News, February 22, 1906.

6 Associated Press, July 18, 1961.

7 Chicago Tribune, July 11, 1912.

8 Milwaukee Sentinel, December 28, 1912.

9 Eddie Cicotte, “The Secrets of Successful Pitching,” Baseball Magazine, July 1918. Accessed online at LA84.org.

10 Grantland Rice, “The Battle of the Leagues,” Collier’s, October 13, 1917.

11 Bob Hoie, “1919 Baseball Salaries and the Mythically Underpaid Chicago White Sox,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Spring 2012), 29. Cicotte also agreed to a “substantial” off-contract performance bonus, which he didn’t earn in 1918. But after rebounding to a stellar 29-7 season in 1919, Comiskey paid him an additional $3,000 that, according to Hoie, was “likely a carryover from the 1918 agreement.” Hoie writes that in terms of total compensation, Cicotte was the second highest paid pitcher in baseball in 1918-20 behind Walter Johnson.

12 Bill Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2013), 50-51.

13 Ibid.

14 Boston Globe, October 1, 1919.

15 Chicago Tribune, October 5, 1919.

16 Christy Mathewson, New York Times, October 16, 1919.

17 Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1920.

18 Lamb, 49-50. According to the notes taken by Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle, who was present in Austrian’s office for the meeting, Cicotte initially named Fred McMullin, Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, Joe Jackson, and Happy Felsch as “the men who were in the deal.” Cicotte apparently did not mention Swede Risberg‘s name in Austrian’s office. But in his grand-jury testimony later that day, he did name Risberg as being present at two September players’ meetings discussing the fix, one at the Ansonia Hotel in New York and one at the Warner Hotel in Chicago.

19 Lamb, 51.

20 Jacob Pomrenke, “The Black Sox: After the Fall.” The National Pastime Museum, April 4, 2013. Accessed online at http://thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/black-sox-after-fall.

21 Joe Falls interview with Cicotte, Detroit Free Press, December 4, 1965.

Full Name

Edgar Victor Cicotte

Born

June 19, 1884 at Springwells, MI (USA)

Died

May 5, 1969 at Detroit, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.