July 5, 1912: ‘Magician-like’ Christy Mathewson sours Brooklyn’s grins while earning 300th career win

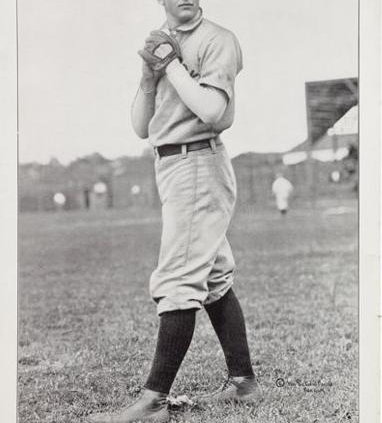

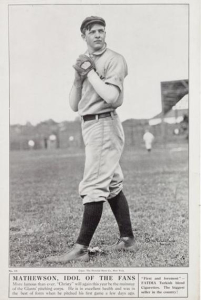

Despite watching Cy Young pitch effectively into his 40s in the preceding seasons, many baseball fans and journalists once again characterized 31-year-old Christy Mathewson as old and washed up in 1912, using every average or poor outing by the New York Giants ace as an excuse to wonder aloud if “Big Six” should change his nickname to “Big Retired.”

Despite watching Cy Young pitch effectively into his 40s in the preceding seasons, many baseball fans and journalists once again characterized 31-year-old Christy Mathewson as old and washed up in 1912, using every average or poor outing by the New York Giants ace as an excuse to wonder aloud if “Big Six” should change his nickname to “Big Retired.”

“The permanent passing of ‘Old Cy’ Young from the big league[s] leaves but a single man believed to have any sort of chance to equal the famous Ohioan’s pitching record, and already fandom is looking at that man askance,” wrote Hearst Newspapers’ Damon Runyon in June 1912, less than a year after the end of Young’s 22-season major-league career. “Every time ‘Big Six’ loses a game nowadays, the question is asked: ‘Is Matty going back?’ Little attention is paid to his winnings. Gotham is accustomed to seeing him win: It is only when he drops a game that he attracts attention. Some contend that Matty’s curves are not breaking in the old way, and that he is slowly but surely retrograding, but you can’t get ball players to take any stock in that theory.”1

Take Joe Tinker, the Chicago Cubs shortstop, for instance. He said: “Any time a man can pick nine strikes out of ten thrown balls and retire the side, you can [bet] your little bank roll that he isn’t going back very far. Control like that will win even after his curve is gone.”2

Or take the Brooklyn Dodgers, who quickly learned not to underestimate the big Pennsylvanian that July.

On July 4 the Dodgers had knocked Mathewson out of the game and snapped New York’s 16-game winning streak. After Mathewson surrendered five runs in the first three innings, manager John McGraw lifted him from the game and watched as the Dodgers swept the doubleheader.3 So Brooklyn’s hitters wore what the New York Times described as “broad grins” when Mathewson, out for revenge, returned to the Polo Grounds mound to start the next day. But with “a back-breaking fadeaway, saucy inshoots, deceptive out-hops, a slow ball that hesitated in midair two or three times before reaching the pan, and control which kept the pill under magician-like influence,” Mathewson instead made the Dodgers appear “as if they had been eating too much watermelon”4 in a 6-1 Giants win. He picked up his 300th career victory in front of 5,000 fans in the process.

Action went against the Dodgers from the start, as Cy Barger walked leadoff man Fred Snodgrass and Beals Becker followed with his first home run of the season. Red Murray sent a one-out single to right and moved ahead on Buck Herzog’s groundout before Jack Meyers rapped a clutch RBI single to center for a 3-0 New York lead.

Brooklyn manager Bill Dahlen – himself familiar with how effective Mathewson could pitch from their days together as Giants teammates from 1904 to ’075 – took no chances and pulled Barger from the game before he could record the third out, marking the third time Barger had failed to get out of the opening frame against the Giants over his first 68 career starts.6 New York stranded runners on the corners when rookie reliever Maury Kent got Heinie Groh to pop out in foul territory, but Barger’s poor showing left him with his second of six consecutive losses in July.

New York continued its rally in the second. Mathewson helped his own cause with a leadoff single, and he “went down to second as if he was after an Olympic record” for his 15th career stolen base.7 Murray sent a Texas Leaguer between three Dodgers, and after one of the players kicked the ball, both Mathewson and Fred Merkle, who had walked, crossed the plate for a 5-0 lead.

The Dodgers scored in the fifth after a combination of singles and infield groundouts allowed Bert Tooley to slowly but surely round the bases. Brooklyn recorded two of its five hits in the inning.

In the eighth, Meyers and Art Fletcher hit back-to-back one-out singles for the Giants, and on Groh’s grounder Meyers advanced to third while Fletcher was forced at second. When Meyers and Groh took off on a double steal, Brooklyn catcher Otto Miller initially threw to second. By the time second baseman John Hummel threw back to the plate, his low throw gave Meyers plenty of time to score the game’s final run.

Though Mathewson did not record a strikeout, he allowed only five hits and a walk while stifling Brooklyn for nine innings. With his 300th career win, Mathewson became the eighth pitcher in major-league history to reach the mark and the first to do so without pitching in the 1800s.

But in another example of the pervasive opinion about Mathewson’s age, one report the next day stated that he “made the Dodgers look like bush leaguers, but Matty is growing old in the game and can not be depended on as in days gone by.”8

Occasional criticism of Mathewson’s skills had followed him for years. Because he was widely considered the best pitcher in baseball in the first half of the decade, fans and journalists seemed to hold Mathewson to a higher standard than many of his peers. In 1908, for example, he lost three straight games, prompting the New York Times to suggest “the star of Christy Mathewson has set.”9 A week later, when he lasted only two innings against the Cubs, the Times wrote, “All signs of his former greatness had flown by the time the Cubs got through with him.”10 Mathewson responded with back-to-back shutouts, and he lost only eight more times that season while sealing up his second pitching Triple Crown with 37 wins, a 1.43 ERA, and 259 strikeouts.

In 1911 fans swooned over Mathewson’s protégé, Rube Marquard, who burst into the starting rotation with a blazing fastball and a wicked curve, and his 237 strikeouts led the NL and helped push the Giants into the World Series. When the 25-year-old Marquard opened the 1912 season with 19 straight victories, his on-field success, youthful exuberance, and big-city personality won fans over. Marquard began receiving ovations that out-thundered those bestowed upon Mathewson, and reporters and fans accepted that Marquard had surpassed Mathewson in performance and popularity.11

But just as Mathewson did in 1908, he proved his doubters wrong. After his win on July 5, New York’s record improved to 55-13, a continuation of one of the finest season-opening stretches in history.12 The Giants stood 14½ games ahead of the Chicago Cubs and Pittsburgh Pirates in the National League standings after the win, while Brooklyn fell to 27-41 on the way to their ninth straight losing season (58-95).

“The Giants are now in the National League race so far in front that some experts declare there is not a possibility of the club being overtaken. I leave a statement of that sort to experts,” Mathewson said a few days later. “Nothing is sure in baseball until it is accomplished. But with the New York club leading the field as it does, it seems reasonably certain that the team will stick ahead until the end of the race.”13

By season’s end, the Giants had won 103 games to capture their second of three straight NL pennants. New York finished with a 10-game lead over the Pirates but could not get past the 105-win Boston Red Sox in the World Series.

Mathewson certainly did his part to get the Giants to the top. After beating Brooklyn, he won his next four starts and compiled a 12-7 record with a 1.98 ERA through the end of the season. And though Mathewson took two one-run losses in the 1912 World Series, manager McGraw said those games – along with his 11-inning Game Two effort that resulted in a tie – conclusively refuted all suggestions that Mathewson had passed his prime.

“He pitched three games in which but one earned run was made against him,” McGraw said. “Those three games were the best, in my opinion, that he had ever pitched. And, after years in baseball, I confidently believe that Christy Mathewson is the best man who ever pitched the game.”14

But Mathewson did not stop there, maintaining his place as one of the league’s elite pitchers by tying Grover Cleveland Alexander with a National League-high 49 wins over the next two seasons before his age finally caught up with him in 1915.15 Mathewson credited his continued success to making adjustments that helped him keep pace with his peers, as “every year, baseball becomes more of a thinking game. Each year, the game becomes just a little bit more complicated. Baseball is demanding more and more a better coordination between brain and brawn.”16

Acknowledgments

This article was fact-checked by Bill Marston and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted the Baseball-Reference.com, Stathead.com, and Retrosheet.org websites for pertinent materials and box scores. He also used information obtained from news coverage by the New York Times, the Brooklyn Standard-Union, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, and the New-York Tribune.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1191207050.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1912/B07050NY11912.htm

Notes

1 Damon Runyon, “Mathewson Still Reigns,” Sioux City (Iowa) Journal, June 23, 1912: 31.

2 “Christy Mathewson Praised by National,” Knoxville (Tennessee) Sentinel, June 13, 1912: 12.

3 The Giants also carried a 16-game winning streak into a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies on July 4, 1904, and earned the sweep to extend the streak to 18 games. Philadelphia beat New York in extra innings the next day.

4 “Old Man Mathewson Grows Young Again,” New York Times, July 6, 1912: 8.

5 Dahlen’s efforts at shortstop helped Mathewson compile 110 wins and a 2.02 ERA during those years. Because Mathewson often pitched to contact instead of trying to strike out hitters, strong defense from players like Dahlen, who finished as the runner-up in fielding percentage among NL shortstops three times with the Giants, was crucial to New York’s success.

6 Barger lasted only two-thirds of an inning against the Giants on April 15, 1911, when Larry Doyle’s comebacker knocked one of his fingers out of joint. Later that season, on October 5, Barger surrendered six runs on three hits and four walks in one-third of an inning against New York in his shortest career start. (He matched his futility mark when he allowed six runs on four hits and a walk against the Phillies on April 15, 1912.)

7 “Old Man Mathewson Grows Young Again.”

8 “Giants’ Pitching Staff Is Off Edge,” Buffalo Times, July 6, 1912: 8.

9 “Matty Forced to Retreat Once More,” New York Times, May 19, 1908: 8.

10 “Cubs Win in Tenth,” New York Times, May 26, 1908: 8.

11 Larry D. Mansch, Rube Marquard: The Life And Times of a Hall of Famer (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998), 106.

12 As of 2023, no American or National League team has ever reached 55 wins faster than the 1912 New York Giants.

13 “Giants Have No Cinch on Flag,” Washington Post, July 7, 1912: 4.

14 “‘Little Napoleon’ of Baseball Says Best Team Won in World’s Series,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, November 9, 1912: 9.

15 Mathewson closed his career in 1916 with 373 wins, second only to Cy Young (511). Through the 2022 season, he stands tied for third with Grover Cleveland Alexander behind Young and Walter Johnson (417). Had Mathewson not won his lone start with the Cincinnati Reds, he would have become the first 300-win pitcher to record all his victories with one franchise.

16 Philip Seib, The Player: Christy Mathewson, Baseball, and the American Century (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 2003), 83.

Additional Stats

New York Giants 6

Brooklyn Dodgers 1

Polo Grounds

New York, NY

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.