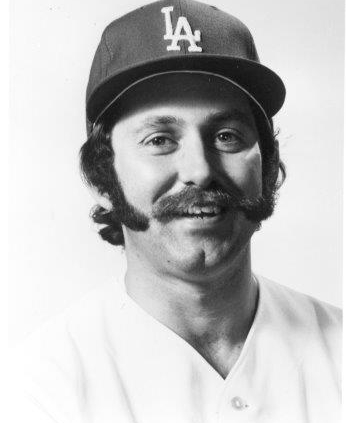

Mike Marshall

Mike Marshall did everything wrong, according to baseball’s establishment. He looked all wrong for a pitcher, standing just 5-feet-8½.1 He believed in pitching more, not less. He worked out with weights and ran long distances instead of wind sprints. He threw a screwball, which breaks the wrong way from a curve. He refused to sign autographs for most of his career because he didn’t believe ballplayers should be heroes. Even his pickoff move turned the wrong way.

Mike Marshall did everything wrong, according to baseball’s establishment. He looked all wrong for a pitcher, standing just 5-feet-8½.1 He believed in pitching more, not less. He worked out with weights and ran long distances instead of wind sprints. He threw a screwball, which breaks the wrong way from a curve. He refused to sign autographs for most of his career because he didn’t believe ballplayers should be heroes. Even his pickoff move turned the wrong way.

Worst of all, he often declared that he cared more about the competition than about winning. “I’m an educator and baseball is my hobby,” he said. “I enjoy throwing a baseball. The money is nice but it won’t dictate my life.”2

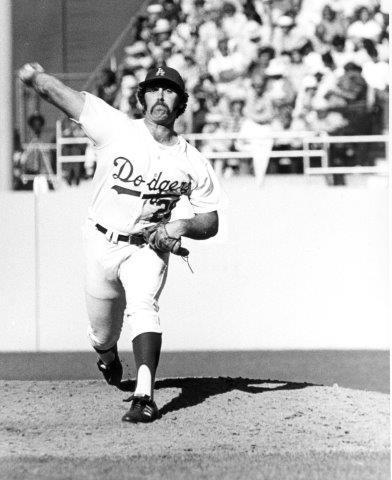

In 1974 the 31-year-old right-hander appeared in a major-league record 106 games for the Los Angeles Dodgers, pitching 208 1/3 innings in relief. His season is unique in baseball’s long history. Nobody else has come close to 106 games, not even in the 19th century, when pitchers were just 50 feet from home plate and throwing underhand.

What was he thinking?

He was thinking he knew better. And he backed up his opinions with science. While he was an active player, Marshall earned a Ph.D. in kinesiology, the study of body mechanics, from Michigan State University. Whenever sportswriters asked him, for the umpteenth time, how he could pitch practically every day, he replied, “I could explain why, but I don’t have the time and you wouldn’t understand if I did because of your lack of physiological background.”3 Writers called him rude, arrogant, a snob.

He also alienated managers, coaches, and some teammates. “Pitching coaches are like the medicine men of the distant past,” he said. “Some don’t have a clue, and they don’t have a clue that they don’t have a clue, which is worse.”4 Stating the obvious, he added, “I was totally uncoachable.”5

He would argue with a doorknob. “Mike would tell a Persian how to make a rug,” an anonymous teammate commented. “Or Betsy Ross how to make a flag.”6

Marshall was called “Iron Mike,” the pitching machine. But he was flesh and blood and muscle and bone, and he believed he had conditioned his body better than anyone else by using his knowledge of kinesiology to design a training program. “Really, the secret to training—at least my training—is specificity,” he said. “If you’re a pitcher, you pitch. If you’re a hitter you hit.”7 He threw every day, sometimes pitching batting practice or working out at shortstop. He ran, or jogged, up to four miles a day. He lifted weights when that was supposed to be for football players.

He was not an impressive physical specimen despite thick shoulders and arms. He was short, blocky, with a roll around his middle in his prime years. And he was never an overpowering pitcher, giving up nearly one hit per inning with slightly above-average strikeouts and a strikeout-to-walk ratio of less than 2-to-1. He did have an impressive pair of sideburns that would have done the original General Burnside proud, but writer Ron Fimrite thought “he could have passed for a life-insurance salesman.”8

One who understood Marshall’s methods was Dr. Frank Jobe, the pioneer of Tommy John surgery. “Kinesiology, I’m convinced, is the secret of pitching,” Jobe said. “Marshall calls it kinesiology, which is the scientific term. I call it body mechanics. In pitching, it’s balance, rhythm and alignment. If a pitcher has those three things, the stresses on the arm are at a minimum.

“The arm wasn’t meant to throw a ball that hard in the first place. But since these guys do, body mechanics are crucial and Marshall has worked them out for himself—and obviously, to perfection.”

Jobe added, “Pitchers and catchers are generally in better condition than other players, but he’s in better condition than other pitchers and catchers. The legs are so important, and he seems to realize this. I think he works harder at it than anyone else.”9

Marshall continued all his life to push his unorthodox theories about the pitching arm and how to keep it healthy but was rejected or ignored by professional baseball. Yet many of his ideas that were ridiculed by traditional coaches have now entered the mainstream of major-league ball.

Michael Grant Marshall was born in Adrian, Michigan, on January 15, 1943, to William Hal Marshall Jr., a draftsman, and his wife, June. When Mike was 11, he and an uncle were riding in a car that was hit by a train. His uncle was killed, while Mike sustained a back injury that would trouble him for years and shape his baseball career.

After high school graduation in 1960, he signed as a shortstop with the Philadelphia Phillies. He also enrolled at Michigan State and began attending classes in the offseasons. He married his hometown girlfriend, Nancy Matthes.

For four years he moved up the ladder to Double A, an above-average hitter who could steal a base but committed an alarming number of errors. Then the trouble started. He wanted to pitch, thinking it would be easier on his aching back than diving for ground balls. The Phillies, not willing to let a player dictate what position he would play, became the first of 11 teams to decide they could do without Marshall’s services.

Sold to Detroit in 1966, he completed his conversion and climbed to the majors the next May at 23, turning in a superb rookie season as the Tigers fell just one game short of the pennant. His 1.98 ERA in 37 relief appearances was the best on the team, and he saved 10 games with only three blown saves.

His reward: a demotion back to the minors. “I realized I couldn’t get out lefthanded batters and started working on a screwball,” he said, but manager Mayo Smith told him to stop throwing it.10 When he refused, the Tigers let him go to the expansion Seattle Pilots, where pitching coach Sal Maglie told him to stop throwing the screwball. The Pilots passed him on to Houston, where manager Harry Walker told him to stop throwing the screwball. The Astros shipped him out of the country to Montreal, his fifth team in four years.

Conventional baseball doctrine held that the screwball was an arm-killing pitch. Marshall, of course, disagreed: “Throwing screwballs is safer than throwing pitches that require baseball pitchers to supinate their pitching forearm through release.” Supinating the forearm means turning your right hand clockwise with the thumb up, the way a right-handed pitcher throws a curve. Marshall’s studies of anatomy taught him that pronating the forearm—rotating the right arm counterclockwise in a screwball motion—is a more natural movement. He threw the screwball 30 to 40 percent of the time and never needed arm surgery.11

When he arrived in Montreal in 1970, Marshall was 27 and had not yet spent a full season in the majors. He had been dumped by four clubs, burning bridges at every stop. He and Nancy had hauled their three daughters from one end of the continent to the other. The family lived in transient apartments in summer and graduate-student housing at Michigan State in winter while he earned a master’s degree and studied for a Ph.D. “We’ve been married for almost nine years now,” his wife wrote about that period, “and the only furniture we have is a set of bunk beds, a television, and a rocking chair that my grandmother gave me.”12

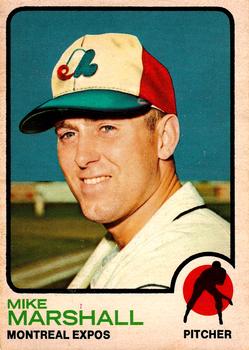

The trade to the Expos turned Marshall’s career around. In 1971 manager Gene Mauch installed him as the late-inning fireman (not yet called a closer). He seized the role. Marshall recorded five saves in April and didn’t allow a run in his first eight appearances. The new pitcher had learned to control his screwball, and his manager stopped trying to control his every breath. Mauch, an old-school manager known as “the little general,” let him train his way and pitch his way. “Gene would say do it your way as long as you don’t try to influence the other players that your way is the right way.”13

In his first year as relief ace, Marshall saved 23 games, second best in the league, with seven blown saves. After 10 years of butting heads with managers and coaches, he had found heaven. “I don’t argue with Marshall,” Mauch said. “He’s extremely intelligent and he’s thinking all the time. He knows what he is doing better than anyone else.”14 Years later Marshall said, “I give Gene Mauch every credit for the success I had in baseball.”15

In 1972 Marshall recorded a career-best 1.78 ERA. He led the league with 65 appearances and compiled 18 saves with a 14-8 record. The next year he set major-league records by pitching 92 games and 179 innings in relief. “I had figured out how to pitch every day without any stiffness or soreness,” he explained.16 He topped the league in saves for the first time with 31 to go with 14 victories, but he also blew 12 saves and lost 11 times. Since he most often came into games in the seventh or eighth inning, he had more opportunities to blow a save than the modern ninth-inning closer.

In 1972 Marshall recorded a career-best 1.78 ERA. He led the league with 65 appearances and compiled 18 saves with a 14-8 record. The next year he set major-league records by pitching 92 games and 179 innings in relief. “I had figured out how to pitch every day without any stiffness or soreness,” he explained.16 He topped the league in saves for the first time with 31 to go with 14 victories, but he also blew 12 saves and lost 11 times. Since he most often came into games in the seventh or eighth inning, he had more opportunities to blow a save than the modern ninth-inning closer.

Success, such a long time coming, only gave him more ways to lodge his foot in his mouth. He refused to accept a $5,000 check awarded to the team’s outstanding player because he didn’t think teammates should compete for such individual awards. That embarrassed the club’s radio sponsor, which sponsored the award.17 A few weeks later he told an interviewer that the Expos’ defense stank—and named names, although he claimed he thought the conversation was off the record.18

Marshall had finished second to Tom Seaver in the Cy Young Award voting and helped the Expos to the best record in the short history of the expansion franchise. But he had worn out his welcome. The club traded him.

He went to the Los Angeles Dodgers for center fielder Willie Davis, who was three years older. Leaving his favorite manager, Marshall was apprehensive: “My first impression is one of sadness. I don’t think it’s good timing at the moment to say good things about the Dodgers. I know they have a good reputation and they know I must work frequently to be effective.”19

Now Marshall had to convince Dodgers manager Walter Alston to buy into his program. “I’ll let you know if I’m not able to pitch on a certain day,” he told the manager, “otherwise you can pitch me every day if you feel that I can help you win a ball game.” Alston believed him. “Walter Alston was a beautiful human being,” he said.20

Marshall began his 1974 season by pitching on five straight days. Starting on June 18, he worked 13 consecutive games in 16 days (breaking the major-league record of nine straight games), and during that stretch he picked up five victories in six days. His 106 appearances eclipsed his own year-old record of 92. Since then, Kent Tekulve and Salomon Torres have pitched 94 games in a season, the closest anyone has come to Marshall as of 2021.

He pitched on consecutive days 53 times, in both games of a doubleheader once. “I firmly believe he can pitch every day and it doesn’t hurt him physically,” Alston said. “The latter point he swears to and I firmly believe he’s a totally honest man. My only concern is overpitching him but frankly, that doesn’t seem possible, does it?”21

Once, after three days off, Marshall said, “If I hadn’t pitched tonight, I would have had to pitch batting practice tomorrow. It seemed like I hadn’t pitched in a year.”22 Counting the All-Star Game, league playoffs, and World Series, he appeared in 114 games and 222 1/3 innings in 192 days.

Alston used him in the typical fashion for relievers in that era. Marshall was called on to finish games whether the Dodgers were ahead, tied, or behind, often as early as the sixth inning. Most of his appearances came in non-save situations. “Mike Marshall gives us the luxury to do things we could not do before,” Alston said. Marshall’s workload enabled the Dodgers to carry only nine pitchers instead of the usual 10.23

The results: 2.42 ERA, 141 ERA+, 2.55 strikeout-to-walk ratio, .617 opponents’ OPS, and a 15-11 record. He led the league with only 21 saves, but the save rule in 1974 had been revised to make it more difficult to qualify. A pitcher had to enter the game with the tying or go-ahead run either on base or at the plate, or he had to work three effective innings.24 Under present-day rules, Marshall would be credited with 30 saves.

However, he blew a dozen save opportunities for a 64 percent success rate. He entered 44 games with runners on base, and 41 percent of them scored, a high number. All in all, he did not have a spectacular year. Three relievers posted lower ERAs (in 50 or more innings).

The Dodgers won the pennant, their first since Sandy Koufax retired in 1966. Marshall didn’t allow a run in two appearances in the league playoffs, then relieved in all five games of the World Series. But his teammates only remembered the last one, when they believed his muleheadedness cost them the championship.

Marshall relieved Don Sutton in the sixth inning of Game 5 against the Oakland A’s with the scored tied at 2-2. As the A’s Joe Rudi stepped in to lead off the bottom of the seventh, someone in the Oakland Coliseum crowd threw a whiskey bottle at Dodgers left fielder Bill Buckner. The game was stopped for six minutes. During the delay, Marshall didn’t take any additional warmup pitches even though catcher Steve Yeager and other teammates urged him to stay loose.

When play resumed, Rudi hit the first pitch into the left-field seats for a Series-winning home run. He said he got the fastball he was expecting, because he didn’t think Marshall would try to throw a screwball after standing around for a while. “When you have a delay that long, you gotta throw a few pitches,” Yeager insisted. But the delay lasted only six minutes, and Marshall had just finished warming up at the start of the inning. Rudi’s homer was the only run he allowed in the Series. Some of the Dodgers never forgave him.25

For his record-shattering season, Marshall became the first reliever to win the Cy Young Award and finished third behind teammate Steve Garvey in the Most Valuable Player voting.26 But he refused to acknowledge that he had done anything extraordinary. “I have a simple job,” he said. “I pitch for the Los Angeles Dodgers when they need a relief pitcher. I don’t count appearances, wins, losses, saves or earned run average. I’m just ready to pitch.”27 That was posturing, polishing his image for being above it all. Years later, he boasted, “I did things nobody had ever done. For me not to be considered the best relief pitcher in the history of baseball is silly, just plain silly.”28

Marshall was just as proud that his arm showed no sign of damage from his workload. But the rest of his body was a different matter. The 1975 season was less than two weeks old when he fell to his knees on the mound with a sharp pain in his left side. It felt “like someone stuck a knife in me,” he said. The diagnosis was torn rib cartilage.29 Marshall went on the disabled list, and after he returned to action, he pitched inconsistently for the rest of the season, winding up with a 9-14 record, 8 blown saves and only 13 saves, with a 3.29 ERA in 58 games. He emphasized that the injury had nothing to do with his arm, but more likely was connected to the “love handles” inflating his waistline.30

Marshall was just as proud that his arm showed no sign of damage from his workload. But the rest of his body was a different matter. The 1975 season was less than two weeks old when he fell to his knees on the mound with a sharp pain in his left side. It felt “like someone stuck a knife in me,” he said. The diagnosis was torn rib cartilage.29 Marshall went on the disabled list, and after he returned to action, he pitched inconsistently for the rest of the season, winding up with a 9-14 record, 8 blown saves and only 13 saves, with a 3.29 ERA in 58 games. He emphasized that the injury had nothing to do with his arm, but more likely was connected to the “love handles” inflating his waistline.30

At 32, he hadn’t put many miles on his arm; he had seldom pitched in youth ball or high school and played shortstop for his first four years in the minors. “I didn’t really start pitching until I was 21 and I didn’t throw a screwball until I was 24,” he said. As a result, he crusaded against abuse of young arms. He thought youth baseball leagues should rotate all players to different positions every inning without making winning a priority.31

He recalled that the only teammates who asked his advice about keeping their arms healthy were Don Sutton, Andy Messersmith, and Tommy John. Following his revolutionary elbow surgery in 1974, John enlisted Marshall’s help with rehabilitation: “Mike gave me a series of exercises to do using a shot put, and I did them right up until the end of my career.” John pitched until he was 46. “[W]hen I was with the Oakland A’s, they tested about eight or ten pitchers in their organization. I was 42 at the time, and they concluded that I was the strongest pitcher shoulderwise, strengthwise, and in flexibility than any pitcher in their organization. And I attribute that to Mike Marshall’s exercises.”32 Sore-armed NFL quarterbacks Fran Tarkenton and Billy Kilmer and tennis pro Stan Smith also sought him out.

Marshall’s insistence on having his way landed him in legal trouble during the winter after the 1975 season. While studying for his doctorate at Michigan State, he kept in shape by taking pitching and batting practice indoors in the school’s intramural center. But when players on the nearby tennis courts complained that the baseballs were hazardous, university officials said he would have to reserve the space in advance rather than use it whenever he wanted. Marshall ignored the rule repeatedly and was arrested, triggering a court fight that dragged on for several years.

He was late for spring training in 1976 because of court appearances, and soon angered Dodgers management in his role as player representative. He aired grievances about hotel accommodations in several cities and demanded that sportswriters be banned from the team bus. At the same time, knuckleballer Charlie Hough was pushing him out of the top relief role. When Marshall left the team for another court appearance early in the season, club president Peter O’Malley decided he was causing more problems than he was worth. The Dodgers exchanged several players and cash with the Atlanta Braves in a waiver deal. “The central fact in all this,” columnist Jim Murray wrote, “is that there isn’t a team in baseball that wouldn’t have wanted Mike if it could keep the right arm and throw the rest away.”33

Marshall arrived in Atlanta without his trademark sideburns, like a man eager for a fresh start. But his season ended early because of surgery for a knee injury. The next spring, he again reported late after another arrest in his continuing feud with Michigan State. In his fourth appearance of 1977, manager Dave Bristol came out to relieve him, and Marshall rolled the ball across the infield. He left the team, was put on the disqualified list, and was sold to the Texas Rangers.

The Rangers tried him as a starter, his first starts since 1970, but his season ended in June after he reinjured his right knee fielding a bunt. He had surgery on the knee and, after the season, another operation to repair the back problem that had been hurting him since his childhood car wreck. Turning 35 before the 1978 season, and finally about to complete his Ph.D. degree, he decided to retire.

But he kept up his tough workout routine, and Nancy could tell he wasn’t ready to quit. After the season started, she called Gene Mauch, who was managing the Minnesota Twins. Needing relief help, he asked Marshall to work out with the club.34 “I couldn’t say no to him,” Marshall explained.35 But owner Calvin Griffith could; he said he couldn’t afford the pitcher’s salary, now well over $100,000. Several Twins players, including six-time batting champion Rod Carew, were enraged by their boss’s penny-pinching. “How can Griffith expect anyone to have any interest in the team when he does something like that?” Carew fumed.36 Marshall got his contract, though at a reduced rate.

Marshall called it his second baseball career. Now that he was financially secure, he said, “This one is for fun.”37 Joining the Twins in mid-May, he appeared in 54 games with a 2.45 ERA, 10-12 record, and 21 saves. After that performance, Griffith signed him to a three-year contract worth $850,000. He earned his salary in 1979 as he revved up to his usual schedule and turned in possibly the best year of his life. He set the American League record by pitching in 90 games, led the league with 32 saves, a career high, and rang up a 2.65 ERA and a 10-15 record. His 4.4 Wins Above Replacement (baseball-reference.com calculation) also set a personal best.

Then his second career suddenly went sour. Early in the 1980 season, Mauch began using his relief ace as a mop-up man, bringing him into games that were already lost. Marshall was pitching poorly, but he suspected another reason for his demotion. He said Mauch confirmed it: “It’s this player rep stuff. You gotta stop doing that stuff.”38 Marshall was one of the Players Association’s highest-profile negotiators in a standoff with owners over a new union contract, and Mauch hated the union.

When the two sides reached agreement on an interim contract that postponed the inevitable strike until the following year, the Twins immediately released Marshall. Calvin Griffith, an owner notorious for his vise-grip on his checkbook, chose to eat around $500,000 owed on the troublemaker’s contract. “Mike and Gene Mauch have always been such good friends,” Nancy wrote, “but by the time Mike left they weren’t even speaking to each other.”39

For the rest of 1980 and the first half of 1981, Marshall couldn’t find a job. He was 37, but just a year removed from one of his best seasons. After the 1981 strike, he finally found work with the New York Mets, managed by a fellow former union rep, Joe Torre. Marshall pitched in 20 of the club’s last 43 games with a 2.61 ERA, but the Mets nevertheless released him at the end of the season. He tried out with the Expos the next spring but was cut before Opening Day. Marshall was forced into retirement with 188 saves, then fifth on the all-time list (58th in 2021).

After 17 years of controversy and contention, professional baseball was through with him. He pitched one more game in Triple A in 1983 and continued to pitch in senior sandlot leagues until he was 56. But he was unable to find any organization willing to hire him as a coach. In the 1990s Marshall wrote letters to all 30 major-league teams offering his services. None replied. “They’re still teaching the same motion of the first guy who won a ballgame,” he said. “There’s not one of them who knows anything of science. They think Sir Isaac Newton invented the Fig Newton.”40

He coached at several small colleges for more than a decade, then opened a private pitching academy in the Tampa, Florida, area. He wasn’t trying to get rich; he charged only $10 a day for his course of instruction. His treatise on pitching was posted online for anyone to read. His training program included throwing trash can lids and 12-pound iron balls with 30-pound sandbags strapped to the pupils’ wrists.41 Marshall taught them a pitching motion so mind-bogglingly weird that it makes an onlooker wonder whether the man had ever thrown a baseball before. He insisted the delivery made them “injury-proof.”42

Marshall’s approach influenced Kyle Boddy, founder of Driveline Baseball, one of the leading private pitching labs and a consultant to major-league and major-college teams. Boddy took the name of his coaching clinic from Marshall’s “driveline” concept, the idea that a pitcher’s body and arm should always be driving on a straight line forward toward the plate. Boddy’s training methods entered the mainstream in 2019 when the Cincinnati Reds hired him as their minor-league pitching coordinator. But he and other researchers, including Glenn Fleisig of the American Sports Medicine Institute, took issue with some of Marshall’s theories.43

The pitchers who paid Marshall’s fee generally were not top prospects; they were high schoolers or collegians not likely to be drafted by the majors or washout minor leaguers. Among the handful of big leaguers was Rudy Seanez, a longtime reliever who called on Marshall for help in recovering from injury.

Shortly after the end of his major-league career, Mike and Nancy divorced. She and pitcher Jim Bouton’s ex-wife, Bobbie Bouton, collaborated on a tell-all book about their lives as baseball wives.44 (Mike Marshall and Jim Bouton had been teammates on the 1969 Seattle Pilots and fellow nonconformists fighting for their jobs.) When Marshall died at 78 on May 31, 2021, his three daughters survived along with his second wife, Erica.

Marshall’s legacy, indirectly, includes Brent Honeywell Jr., whose father was his cousin. Marshall taught the screwball to Brent Sr., who passed it on to his son. Brent Jr. made his major-league debut with the Tampa Bay Rays in 2021.45

But Marshall remained an outcast from baseball’s establishment. And he never gave an inch. “I know what works,” he said late in his life. “That’s the greatest truth there is. I have a responsibility to give it back. Nobody wants it? Hey. That’s not my problem.”46

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Norman L. Macht, They Played the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 148. Although rosters listed Marshall’s height as 5-feet-10, he told Macht he was 5-8½.

2 Gordon Verrell, “Marshall: winning isn’t everything,” Long Beach (California) Independent, March 20, 1974: C-1.

3 United Press International, “Iron Mike to Rescue,” San Pedro (California) News-Pilot, July 3, 1974: B11.

4 Macht, 147.

5 Daniel G. Habib, “Mike Marshall, Cy Young Winner,” Sports Illustrated, April 9, 2001. https://vault.si.com/vault/2001/04/09/mike-marshall-cy-young-winner-august-12-1974.

6 Jim Murray, “Goodby, Mr. Rips,” Los Angeles Times, June 27, 1976: III-1.

7 Verrell, “Marshall lets his arm do the talking,” Long Beach Independent, July 9, 1974: C-3.

8 Ron Fimrite, “He Also Serves Who Only Sits and Waits,” Sports Illustrated, August 12, 1974, https://vault.si.com/vault/1974/08/12/he-also-serves-who-sits-and-waits..

9 Ted Green, “The Pitching Machine,” Los Angeles Times, July 25, 1974: III-4.

10 Macht, 149.

11 Mike Marshall, email to the author, October 18, 2009.

12 Bobbie Bouton and Nancy Marshall, Home Games (New York: St Martin’s/Marek, 1983), 85.

13 Ross Newhan, “Marshall’s Theorem: His Way Is the Right Way,” Los Angeles Times, March 20, 1974: III-1.

14 Dink Carroll, “Mike Marshall may discover new manager not like Mauch,” Montreal Gazette, December 11, 1973: 46.

15 Macht, 150.

16 Macht, 150.

17 Newhan, “Davis and Dodgers Get the Trade They Wanted,” Los Angeles Times, December 6, 1973: III-1.

18 Ian MacDonald, “Expo defence: ‘Who Wants to go back to that?’ — Mike Marshall,” Montreal Gazette, November 15, 1973: 29.

19 Don Merry, “Willie D. dealt for relief whiz,” Long Beach Independent, December 6, 1973: C-1.

20 Macht 152.

21 Green, “Pitching Machine.”

22 Newhan, “Marshall Saves Dodgers’ 3-2 Win Over Mets,” Los Angeles Times, June 15, 1974: III-1

23 Fimrite.

24 The 1974 rule was changed after one year so that a pitcher could earn a save if he entered with the tying run on deck.

25 Steve Delsohn, True Blue (New York: Perennial, 2001), 107. I timed the delay on the NBC-TV broadcast, available on You Tube.

26 Before the Cy Young Award was created, reliever Jim Konstanty of the pennant-winning Phillies won the National League MVP Award in 1950.

27 Green, “Pitching Machine.”

28 Habib, “Mike Marshall.”

29 Jeff Prugh, “Marshall, Wynn Hurt in L.A. Win,” L.A. Times, April 20, 1975: III-1

30 Prugh, “Dr. Marshall Diagnoses Injury,” L.A. Times, May 14, 1975: III-7.

31 Ron Rapoport, “Marshall: Sore-Arm Epidemic in Youth Baseball,” L.A. Times, May 6, 1975: III-4.

32 Phil Pepe, Talkin’ Baseball (New York: Ballantine, 1998), 157.

33 Murray, “Goodby, Mr. Rips.”

34 Bouton and Marshall, 157.

35 Macht, 156.

36 Bob Fowler, “Carew: I’m going to stick it to Calvin,” Minneapolis Star, May 12, 1978: 1D.

37 Fowler, “Second Time Around, Marshall Pitches for Fun,” The Sporting News, June 2, 1979: 3.

38 Macht, 156.

39 Bouton and Marshall, 187.

40 Sam Mellinger, “The Marshall Plan,” Kansas City Star, April 4, 2007: D7.

41 Jeff Passan, “Why pitching as we know it today wouldn’t exist without Mike Marshall,” espn.com, June 2, 2021, https://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/31553574/why-pitching-know-today-exist-mike-marshall.

42 Habib.

43 Ben Lindbergh and Travis Sawchik, The MVP Machine (New York: Basic, 2019), 71-72; Glenn Fleisig, interview by author, October 16, 2009. Fleisig co-founded the American Sports Medicine Institute with the renowned orthopedic surgeon James Andrews.

44 Bobbie Bouton and Nancy Marshall, Home Games (New York: St. Martin’s/Marek, 1983).

45 Passan, “Why pitching as we know it.”

46 Passan, “Outside Pitch,” Yahoo Sports, May 10, 2007, https://sports.yahoo.com/jp-marshall051007.html.

Full Name

Michael Grant Marshall

Born

January 15, 1943 at Adrian, MI (USA)

Died

May 31, 2021 at Zephyrhills, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.