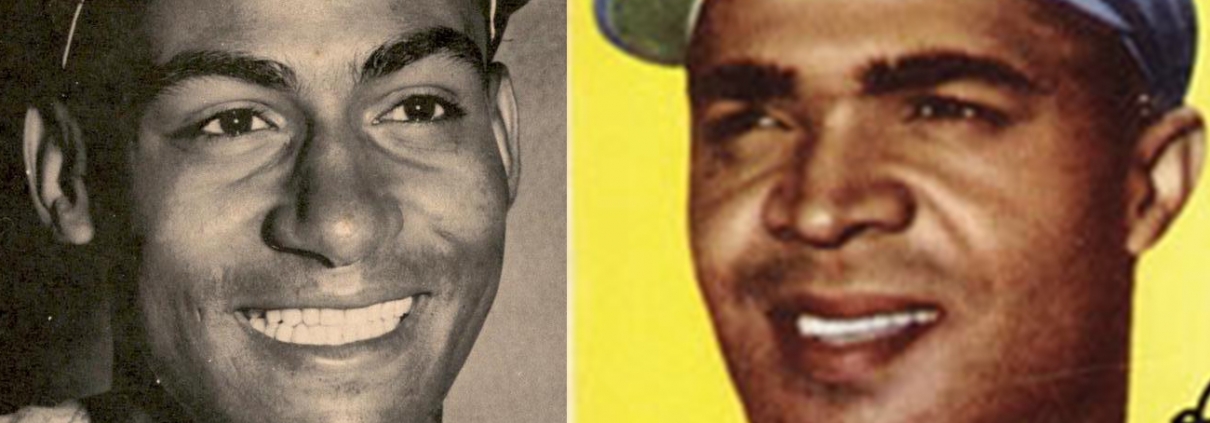

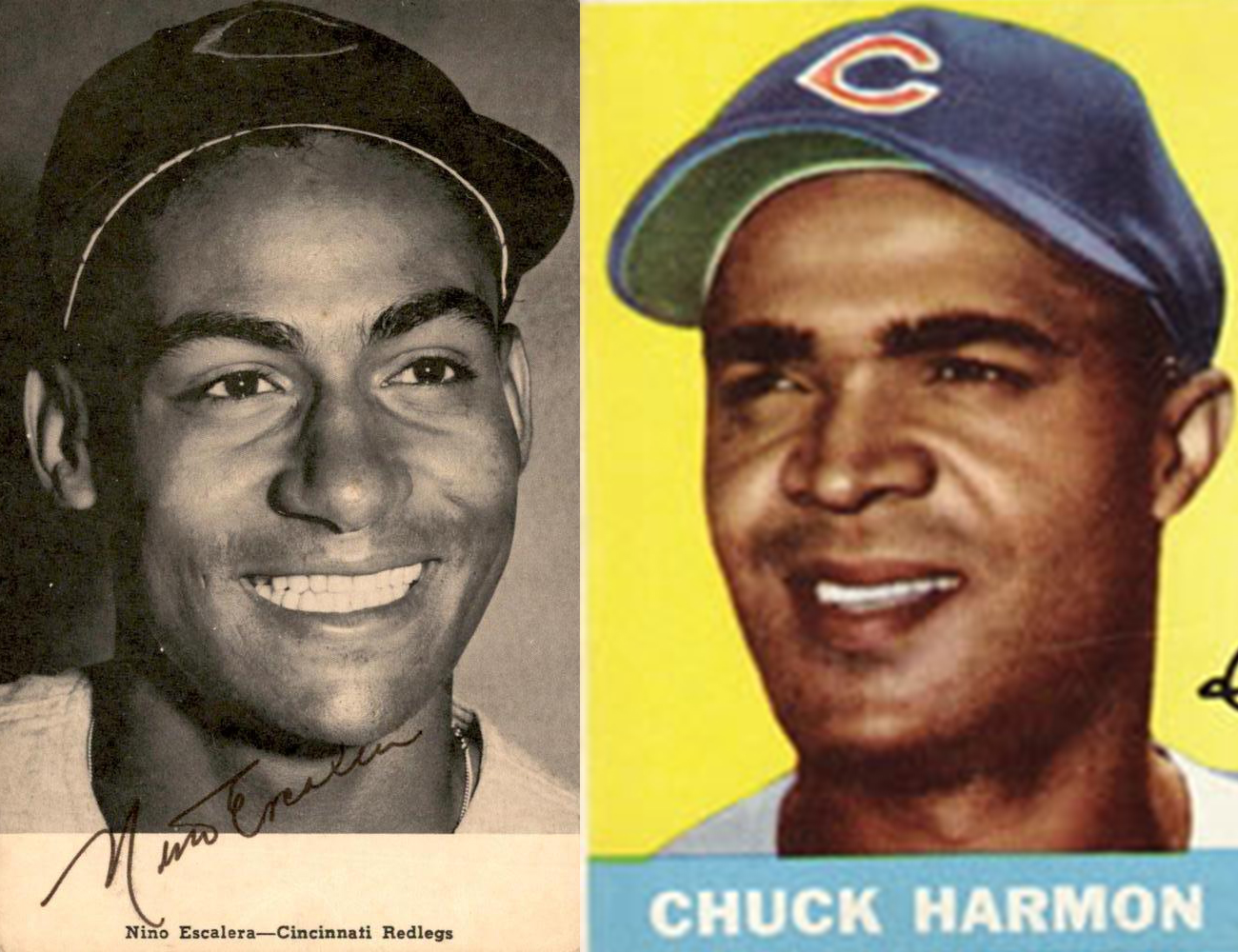

April 17, 1954: Nino Escalera, Chuck Harmon integrate Cincinnati Reds in loss to Milwaukee Braves

Box scores don’t lie. But sometimes they cannot tell the whole truth.

Like a classic novel, whose layers are best understood by reading its criticism, a box score’s secrets can be revealed through game stories. Context enables a deeper understanding of history, allowing the pieces of the puzzle to expose the entire picture.

The April 17, 1954, Cincinnati Reds-Milwaukee Braves game is a perfect example. “Escalera, ph” and “Harmon, ph” appear in the box score, separated by a few lines of type in the Reds’ ledger for a 5-1 early-season loss in Milwaukee, but their importance can easily be missed.

They were not merely two pinch-hitters in a losing cause – they were the first two appearances by Black players for Cincinnati, 72 years after the Red Stockings first took the field in 1882.1

Both Nino Escalera and Chuck Harmon had broken camp with the Reds, though neither was a lineup regular. The 24-year-old Escalera, a native of Santurce, Puerto Rico, was regarded as “one of the most speedy and spectacular members of the Cincinnati Redleg squad.”2 As spring training began, he was noted for “the distinction of being the first colored baseball player to don a Cincinnati uniform.”3 Other observers were less sanguine: “Considered one of the fastest outfielders in the business, but may not be able to hit big league pitching,” legendary Black journalist Wendell Smith asserted in the Pittsburgh Courier.4

Harmon, who turned 30 within days of 1954’s opener, was described as “an outstanding performer in basketball at Toledo University in ’43 … served in the Navy from 1943 to 1946.”5 As March progressed, the club had penciled in Bobby Adams at third base, “unless Chuck Harmon, a 27-year-old [sic] Negro who batted .311 at Tulsa, makes the club. If Harmon continues his fine early work, he might force Adams to move to second.”6

Both men started in the last tune-up contest, on April 11 at Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: “Escalera … smashed an eighth-inning homer with two aboard to break up a tie today and give the Cincinnati Reds an 8-5 victory over the Detroit Tigers. … Pitcher Art Fowler of the Reds was supposed to lead off the batting in the sixth inning, but Third Baseman Chuck Harmon strode up to the plate instead and neither the Tigers nor the umpire challenged the out-of-turn batting order.”7 As Harmon and Escalera made the team, other Black players continued their march through the farm system, including 18-year old prospect Frank Robinson, who started the season with Class A Columbia.

Conspicuous by their absence in the exhibition’s recap were any race qualifiers. As the big leagues continued their inexorable march toward integration, newspaper coverage varied by audience. The Black press noted that “only four teams failed to list a Negro on roster.”8 Given the talent of the pioneers, many scribes mused that those clubs would not hold out much longer: “Robinson and the Negro players who followed him have become dominant factors in major league baseball. This year will be no exception. At least 11 of the sixteen teams have Negroes on their rosters. Before the season ends they may all have at least one.”9

Other periodicals, while noting the demographics of baseball’s newcomers, often failed to comment on the injustices the Black players still faced, especially in the segregated South. In a United Press article carried by many newspapers, Oscar Fraley noted: “This is a day 50 young men will never forget – the day they become big leaguers. They hail from all over, big cities and little towns. … [F]or five of them it goes beyond baseball. … Three are Puerto Rican [including] Cincinnati outfielder Nino Escalera from Santurce.”10

On April 17, 20,938 patrons packed youthful County Stadium, then in its second season of hosting the Braves after their move from Boston. It was the third game of the season for both teams.11

The Reds wasted no time getting on the scoreboard in the first, as leadoff hitter Adams walked and moved to second on Roy McMillan’s single off Lew Burdette. Successive force plays brought Adams home for the only lead the visitors would enjoy.

The home squad followed a similar script against Corky Valentine. The Ohio-born hurler, making his first career start, issued a leadoff walk to Bill Bruton and allowed a single to Danny O’Connell. Eddie Mathews – who later became the only Brave to play for the franchise in Boston, Milwaukee, and Atlanta – singled in the tying run.

Four seasons after Sam Jethroe integrated the Braves franchise, Milwaukee debuted a promising Black player in 1954. Hank Aaron, who had celebrated his 20th birthday in February, led off the second inning. The right fielder, appearing in only his third big-league game, was 2-for-10 thus far in the young season and had not yet connected for the first of his 755 career home runs.

Aaron walked and scored on a round-tripper by Johnny Logan to left, a drive aided by “a strong wind … toward that fence all afternoon.”12 Milwaukee had a 3-1 lead.

Both squads were quiet in the third, fourth, and fifth frames, with neither advancing a runner to third base. The Reds threatened in the sixth, as Jim Greengrass and Johnny Temple both singled to put two on with two out, but Wally Post’s weak comebacker to Burdette ended the threat.

The Braves added two more runs in their half of the sixth. Logan once again homered, this time “a 365-foot blast into left center.”13 Del Crandall then walked, moved to second base on a Burdette bunt, and scored on a single by Bruton, increasing Milwaukee’s lead to four runs.

Cincinnati manager Birdie Tebbetts, whose 14-year playing career was interrupted by World War II, dug into his bench in the seventh – and made history. Escalera slowly walked to the plate as Cincinnati’s first batter of the inning, replacing Andy Seminick in the eighth spot of the batting order.

Escalera, a .300 hitter in almost 600 minor-league games, was patient with Burdette’s offerings. The disciplined left-hander singled and trotted to first, a ground-breaking 90-foot voyage.

Tebbetts was not done. Harmon was the next hitter, replacing Valentine. But a soft fly ball to first baseman Adcock retired Harmon and kept Escalera tied to the bag.

Adams laced a single that moved Escalera to second, but Lloyd Merriman, another pinch-hitter, grounded into a double play to end the threat.

Curiously, Tebbetts had neither Escalera nor Harmon take the field in the bottom of the inning. Art Fowler took over pitching duties and Ed Bailey, a 22-year-old whose two appearances with the Reds in September 1953 were the beginning of a 14-year career, became his batterymate; Rocky Bridges handled shortstop.

Burdette, 27 and at the beginning of a long tenure as a mainstay of Milwaukee’s starting rotation, closed out the Reds in the eighth and ninth to record the win. Evening newspapers noted the final score, but few acknowledged the importance of Escalera’s and Harmon’s roles; Logan’s two blasts and Burdette’s pitching starred in the narrative. The Sporting News gave four sentences to the game but did not mention the appearances.14

Over half a century later, in 2019, it was deemed the 17th best game in Reds’ history by the Cincinnati Enquirer, whose original reporting had plainly stated, “Escalera batted for Seminick and singled. Harmon went up for Valentine. He popped to Adcock.”15

Neither Harmon nor Escalera enjoyed long major-league careers.16 Harmon played 289 games with the Reds, Philadelphia Phillies, and St. Louis Cardinals, producing a 62 OPS+ (.238/.294/.326). He remained a popular figure in Cincinnati and made numerous appearances through the years for the franchise. An accomplished basketball player who was considered for a spot with the Boston Celtics, Harmon was Larry Doby’s roommate during their military service. After his baseball career, he worked as a deputy clerk with the Hamilton County courts and the Ohio 1st District of Appeals.17 His love for the game was never extinguished, and he scouted for the Braves and Cleveland Indians.18

Escalera made 73 appearances in 1954, his sole year in “The Show.” Both players returned to the minors for several years, and Escalera continued to play in Puerto Rico, where he was recognized as one of the league’s all-time top 75 players. He died on July 3, 2021, in an assisted-care facility.19 With Escalera’s passing, Ozzie Virgil Sr. is (as of 2022) the last living pioneer, having integrated the Detroit Tigers on June 6, 1958.20

Harmon and Escalera paved the way for future Reds Barry Larkin, Tony Pérez, and Joe Morgan, – all Hall of Famers whose plaques sport the “C” – and also for Eric Davis, Dave Concepción, José Rijo, George Foster, and many others who contributed to the franchise’s 1975, 1976, and 1990 World Series championships. Their impact, however, was felt even earlier; by 1956, the team had the most active African American players of any franchise, including future legend Robinson.21 Harmon would play a significant role mentoring Robinson that season.

Spectators who kept their ticket stubs retained more than a record of the contest. The crimson game number would be interpreted as maroon by those with color blindness. On that day, the Reds finally saw beyond race. After decades of having Cuban players like Armando Marsans, Rafael Almeida, and Tomás de la Cruz “pass” for Caucasians, the franchise finally acknowledged a more inclusive future, open to baseball talent from all backgrounds.

Acknowledgments

The article was fact-checked by Ray Danner and copyedited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes below, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for pertinent information, including box scores.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/MLN/MLN195404170.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1954/B04170MLN1954.htm

Notes

1 The living Cincinnati Reds franchise was born in 1882 as an American Association team and migrated to the National League in 1890. The original NL Reds played from 1876 to 1880 before their charter was terminated over a dispute on Sunday baseball and beer sales.

2 Al Warden, “Patrolling the Sports Highway,” Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner, February 22, 1954: 10.

3 Warden.

4 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 6, 1954: 14.

5 Smith.

6 Jack Hand (Associated Press), “Cincy Looking for Effective Righthanders,” Panama City (Florida) News Herald, March 16, 1954: 6.

7 “Reds Beat Tigers,” Hazleton (Pennsylvania) Standard-Sentinel, April 12, 1954: 12.

8 Bill Nunn Jr., “Record Group of Negroes in Majors Opening Day,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 17, 1954: 15.

9 Wendell Smith, “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 17, 1954: 14. The trickle-down effect of social justice was not without its innocent victims, though. Citing the still-lucrative Kansas City Monarchs as the exception, rather than the rule, reporters noted that “the old and established money-markets of Negro professional baseball have long since pulled in their shingles within territory embraced by the major leagues.” “Negro Baseball Still Pay [sic] Off,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 17, 1954: 14.

10 Oscar Fraley (United Press), “Big Day for 50 League Rookies,” York (Nebraska) Daily News-Times, April 13, 1954: 2. Perhaps more damning was a single sentence from the original UP piece, exorcised from various publications: “They shame the political mockery against a land of freedom and opportunity.” Out of 13 paragraphs, only that line was edited out by member newspapers. Fraley, as published in the Neosho (Missouri) Daily News, April 13, 1954: 6.

11 The teams had begun the 1954 campaign four days earlier, with a single game won by host Cincinnati. The rematch would wait, however, as the Reds traveled to Chicago and the Braves hosted the Cardinals for a pair of single games, sandwiched between off days.

12 “Burdette Stops Redlegs, 5 to 1,”Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, April 18, 1954: 61.

13 “Tigers Top Orioles, 1-0; Logan Hits Two as Braves Trip Reds,” La Crosse (Wisconsin) Tribune, April 18, 1954: 29.

14 “National League,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1954: 19.

15 Mark Schmetzer, “Cincinnati Reds 150th Anniversary: 17th Best Game, Escalera, Harmon Debut,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 2019.

16 Less than four months after their debut game, the duo played in the 1954 Hall of Fame Game, a thrilling affair won by the New York Yankees, 10-9. Harmon (playing third base and hitting second in the lineup) and Escalera (manning center field and hitting third) thus also share the honor of being the first Black Reds players to appear in the Cooperstown classic. Earl Lawson, “8,805 See Yankees Rally to Nip Reds in Cooperstown Game,” The Sporting News, August 18, 1954: 14.

17 Andrea Medina and Brian Planalp, “Exhibit Unveiled Honoring Chuck Harmon, the Reds’ First Black Baseball Player,” https://www.fox19.com/2021/07/01/exhibit-unveiled-honoring-chuck-harmon-reds-first-black-baseball-player/, July 21, 2021.

18 WLWT Digital Staff, “Chuck Harmon, Reds’ First African-American Player, Dead at 94,” https://www.wlwt.com/article/chuck-harmon-reds-first-african-american-player-dead-at-94/26882632#, March 20, 2019.

19 Dave Clark, “Nino Escalera, Who Broke Reds’ Color Barrier in 1954, Dies at 91 in Puerto Rico,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 8, 2021, https://www.cincinnati.com/story/sports/mlb/2021/07/08/nino-escalera-broke-cincinnati-reds-color-barrier-1954-dies-91-puerto-rico-obituary/7898596002/.

20 Sam Gazdziak, “Obituary: Nino Escalera, 1929-2021,” RIP Baseball, https://ripbaseball.com/2021/07/05/obituary-nino-escalera-1929-2021/, July 5, 2021.

21 “Cards That Never Were,” February 25, 2021, http://cardsthatneverwere.blogspot.com/2021/02/barrier-breakers-1954-nino-escalera.html.

Additional Stats

Milwaukee Braves 5

Cincinnati Reds 1

County Stadium

Milwaukee, WI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.