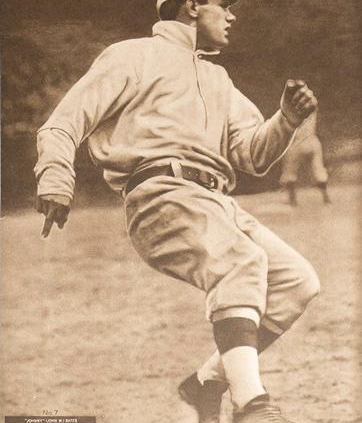

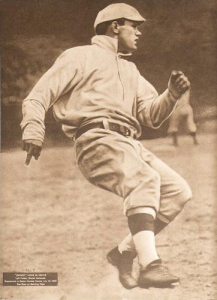

Johnny Bates

The 1906 season opened for the Boston Beaneaters in Brooklyn on April 12. Making his major-league debut that day with Boston was outfielder Johnny Bates, a compact left-handed swinger (5-feet-7 inches and around 170 pounds). Batting fifth in the lineup, Bates strode to the plate to face Harry McIntire in the second inning. The 22-year-old gained instant note — “he caught one of McIntire’s high fast shoots squarely on the nose and sent it skimming over the fence” for a home run.1 It was the only run Boston needed in their 2-0 win. The opening shot was a portent: Bates had a team-leading six of his team’s 13 homers that year.

The 1906 season opened for the Boston Beaneaters in Brooklyn on April 12. Making his major-league debut that day with Boston was outfielder Johnny Bates, a compact left-handed swinger (5-feet-7 inches and around 170 pounds). Batting fifth in the lineup, Bates strode to the plate to face Harry McIntire in the second inning. The 22-year-old gained instant note — “he caught one of McIntire’s high fast shoots squarely on the nose and sent it skimming over the fence” for a home run.1 It was the only run Boston needed in their 2-0 win. The opening shot was a portent: Bates had a team-leading six of his team’s 13 homers that year.

Bates played in the majors through 1914 and continued in minor-league ball until 1923. After that the semipro game kept him going well past his 50th birthday. A headline in 1926 summed up his style, calling him a “plugger type of ball player, never star, but always dependable.”2

Current fans are likely never to have heard of Bates. If they view his metrics, they see a slightly above-average offensive player (OPS+ of 122 for his career, 100 is average) who was hailed by a Cincinnati writer as “one of the best bunters in the National League [who] can wait the pitchers out as well as anyone, cuts in capably when the hit-and-run is required and is one of the best long-distance swatters.”3 In short, he could handle the bat equally well as a leadoff, two-hole, or clean-up hitter.

It is much more difficult for the modern fan to determine Bates’ fielding talents. His range factor suffers in comparison to teammates and contemporaries some seasons, yet he was described as a wide-ranging fielder who “pulls off many thrilling catches.”4 Modern metrics such as dWAR never give him a positive score (labeling him below average compared to all fielders). He played all three outfield spots but was used more in center field than either of the corners.

Born John William Bates on January 10, 1884, he was the sixth of 15 children born to Thomas and Margaret (Grant) Bates.5 His parents were English and had started the family there before coming to the United States in 1881. Thomas was a coal miner and the family settled in Jefferson County, Ohio, living in Bloomfield and Steubenville, where John was born.

Bates attended school in Steubenville and noted on a census that he had one year of high school. According to the 1900 census he was in the work force, having joined a couple of brothers at the local glassworks. He no doubt learned baseball from his brothers and on the open lots in Steubenville. By 1904 he was a member of the local team, playing center field and batting in the middle of the order.6

Bates began collecting a paycheck to play baseball in 1905 when he signed with Altoona in the independent Tri-State League.7 Bates played left field for the Mountaineers and batted either leadoff or second. He was released after about a month and signed on with Homestead, Pennsylvania.8 He closed out the season playing center field for Sharon (Pennsylvania) in the Ohio-Pennsylvania League.9

Boston Beaneaters catcher Tom Needham lived in Steubenville. He recommended Bates to Boston management and in February 1906, Bates was signed by the team.10 While his debut home run made his name known to the fans, it was his play in the field that garnered praise from the press, with one writer saying, “Johnny Bates is certainly breaking in well. He covers that center garden with the confidence and skill of an old-timer.”11 Boston fans needed every excuse to cheer in 1906 because the team suffered through a horrendous 19-game losing streak in May and June that included nine shutouts. During these 19 games, Boston scored 29 runs while yielding 123.The team never escaped the cellar after that. Bates supplied what little power the team could generate. He led the Beaneaters in doubles (21), home runs (6), and slugging percentage (.349).

The Boston franchise was sold to the Dovey brothers before the start of the 1907 season, which led to a new nickname for the team: “Doves.” Bates found himself in right field for the season after the winter acquisition of Ginger Beaumont. Bates started the season poorly at the plate and was batting just .167 on April 26 before a game in Brooklyn against the Superbas. Batting leadoff, he hit for the cycle and added a stolen base as the Doves won, 4-2. His average continued to climb and peaked at .297 when he had another four-hit game — featuring a triple, two doubles, and a single — against the Superbas on May 28.

Bates became a fan favorite. He was awarded a gold watch and a five-pound box of chocolates in August by his followers. He reportedly sent the candy home to Steubenville for his sisters to enjoy.12 He closed out the year batting .260 in 126 games.

Honus Wagner had been involved with a touring basketball team in the winter of 1906-07. In the fall another team was organized that included Bates playing guard. Wagner’s brother Al was to manage and play; the group was hoping to schedule a tour of New England.13 Results of the games have proven elusive.

The Doves headed to Augusta, Georgia for spring training in 1908 with Joe Kelley assuming the managerial post. A stretch of inclement weather drove the players indoors at the local YMCA where they traded the baseball for a basketball. Jeff Pfeffer’s team was matched against Irv “Young Cy” Young’s team. Bates was the star for Young’s squad but Pfeffer’s prevailed.

The weather cleared and warmed in time for the exhibition swing. The Doves slowly made their way north playing minor-league teams along the way. Bates batted leadoff and alternated among the outfield positions. When the season began, his versatility as a hitter made him useful to Kelley. Playing mostly left field, he batted from first to fifth in the lineup. His slash line of .258/.315/.324 does not appear impressive, but his OPS was 43 points higher than the team average, and all his numbers surpassed the team overall. He also led the squad with 25 stolen bases. He tied for the team lead in triples (6) with Ginger Beaumont and George Browne. The lack of offense relegated the Doves to sixth place.

Bates had a hot bat in 1909. In early July, he was leading the team in hitting (.291), extra-base hits (19), stolen bases (15), and chances in the outfield from his left field position.14 Yet the team was batting just .230 and stood in last place. On July 16 the Boston Herald ran a large ad telling fans that a free picture of Bates would be available in the paper on Sunday. Later that day word came that Bates, along with Charlie Starr, had been swapped to the Philadelphia Phillies for pitchers Buster Brown and Lew Richie and infielder Dave Shean. Dealing Bates led to the resignation of Frank Bowerman as Doves manager.15

Bates debuted with the Phillies on July 19, batting second behind Eddie Grant and playing center field. His strong hitting continued: he batted .293 with Philadelphia and added 22 stolen bases in 77 games. The deal did little to affect the standings as Philadelphia finished in fifth and Boston remained in the cellar.

Under Red Dooin the 1910 Phillies inched into fourth place. It was the first time Bates played with a team that made it to the first division. His slash line of .305/.385/.420 was the best of his career but was second to teammate Sherry Magee in each category. Playing mostly center field, he led the Phillies outfielders in chances and range factor, as might be expected. Unexpectedly, his 24 assists led the outfielders and were his career high.

In October, as an outgrowth of talks between Dooin and Clark Griffith, the Cincinnati manager, a major trade was announced. The Phillies would send Bates, third sacker Grant, and two pitchers, George McQuillan and Lew Moren, to Cincinnati for third baseman Hans Lobert, outfielder Dode Paskert, and two pitchers, Fred Beebe and Jack Rowan.16 Two days after the managers had agreed to the deal, Horace Fogel, president of the Phillies, wired Cincinnati owner, Garry Herrmann, that he, Fogel, would not sanction the deal.17

The two teams wrangled over the next two weeks until finally agreeing to the four-for-four swap. Cincinnati fans were fearful that they had gotten the short end of the deal, but former Philadelphia manager Billy Murray told a different tale. He extolled the virtue of each man the Reds were adding, noting in particular, “I consider Johnny Bates one of the greatest outfielders in the National League and in the swap of Paskert for Bates the Reds get an even stronger player in return.”18

Bates wintered in Steubenville, where he prepared for his nuptials with Elizabeth Watkins Briggs. The pair got married on March 7, 1911 — the eve of spring training. Over the years, many a player has honeymooned at training camp, but Elizabeth did not make the journey to Hot Springs, Arkansas. She may have been occupied with child care. The obituary of Johnny Bates listed a son, Robert G. Bates. A census listing for 1910 showed a Robert Briggs, aged 8, living with Elizabeth Watkins Briggs. One may assume that Robert was adopted by Bates, but no definitive proof of this has been uncovered.

The trade proved to be a flop for Cincinnati. Grant hit .223, pitcher George McQuillan went 2-6. while Moren developed shoulder problems and never pitched in the majors again. Only Bates brought a smile to faces of Queen City fans. He covered the outfield with élan and played a crucial role in Griffith’s style of offense. The Old Fox’s plan called for his men to work the count versus opposing pitchers and to disrupt a hurler’s concentration with the running game. (The team was second to the champion Giants in steals.)

Bates batted second in the lineup behind Bob Bescher, who had a career-high 102 walks and stole a league-leading 81 bases. Bates became a model for coaxing a walk and led the team with 103 (he was second in the league). He added 33 steals of his own and contributed 19 sacrifices. His OPS of .808 led the team and was 105 points higher than Paskert’s. The collapse of the two pitchers from the trade contributed heavily to the Reds’ sixth-place finish.

Bates burst from the gate in the 1912 season and was batting .355/.487/.495 when the first-place Reds hosted New York on May 18. Bates scored the winning run in the eighth inning against Christy Mathewson. Unfortunately, he badly injured his ankle on the play and was sidelined.19 He made a few pinch-hit appearances before returning to the field on June 17. The Reds had gone from a 21-9 record to 29-24 in his absence. He struggled physically over the remainder of the season and missed an additional three weeks in September. In 81 games he batted .289.

Joe Tinker took over as player/manager in 1913. Bates came out slugging and hit three home runs in April on his way to leading the team with six. He saw the bulk of his action (92 games) in right field as the Reds limped through the season to finish seventh. Bates batted .278.

The revolving managerial door in Cincinnati welcomed Buck Herzog in 1914. Bates patrolled center field, but his hitting fell off to .252 and he made nine errors in 58 games. On July 8 the Reds released him. Cubs manager Hank O’Day had been Bates’ skipper in 1912 and quickly signed Bates for Chicago. That relationship was short-lived — Bates played in only nine games, mostly as a pinch-hitter.

When the Cubs released him, Bates caught on with the Baltimore Terrapins of the Federal League. For the first time in his career, Bates found himself in a pennant race. He was installed as the left fielder, batting third. After about 10 games he moved to center field. Bates returned to the style he had played with Griffith and forced the pitchers to throw strikes or suffer the consequences. In 59 games he drew 38 walks and posted a .305/.429/.384 slash line. It wasn’t enough, however — the Terrapins went 30-28 after his signing and finished in third place.

Bates had signed a one-year deal with Baltimore. In January 1915, the club announced that he would not be offered another and that he was a free agent.20 He tried to catch on with the Pittsburgh Pirates, the closest team to his Steubenville home, but was told they did not need him. He signed with the Richmond Climbers of the International League.

Richmond was managed by Jack Dunn, who sent Bates to center field and batted him third in the lineup. Bates became an instant favorite, the local paper gushing, “Johnny Bates showed his old-time fire yesterday both in fielding and at bat. His homer was a beauty, while his work in the gardens was a sight worth witnessing.”21 Later in the season, when the Climbers added George Twombly, Bates moved to left field. He led the last-place squad in doubles (27) and walks (106) while batting .296 in 141 games.

Dunn sold off his ownership in the Richmond team and purchased the Jersey City franchise, moving it into Baltimore. In March he added Twombly and Bates to his roster for the Orioles.22 Bates opened the season in a slump but three hits on May 2 jump-started another successful offensive season.23 He played 118 games, mostly batting leadoff. Arguably his best game came July 27 when he had a perfect day with two doubles, a single, and two walks to go with four runs scored.24 He closed the year batting .312.

Bates became something of a baseball nomad after that season. Baltimore did not retain him for 1917, so he signed with the Louisville Colonels in the American Association. He made just a few appearances before being released in late April. He went north to play left field for Roger Bresnahan in Toledo of the AA.25 According to the Reach Baseball Guide he played 79 games and batted .285 in the league. Toledo let him go in late July and he closed out the year with Chattanooga in the Southern Association, appearing in 49 games and batting .293.

Bates began 1918 batting leadoff for the Mobile Bears of the Southern Association. Ever since his season with Griffith in Cincinnati, Bates had been very selective at the plate, gaining the reputation as a waiter. On June 20 he walked all five times he came to the plate against Chattanooga and scored four times.26 The league folded on June 28; on the Fourth of July, Bates was batting leadoff for the Buffalo Bisons in the International League. In August Bates contacted the Baltimore Dry Dock Company. about employment and their baseball team. His last game with Buffalo was August 9 before he headed to Baltimore. A local writer remarked that “he will be missed and his place will be hard to fill.”27

Bates worked for the company and played for the Dry Dock team through 1920. While he played semipro ball in Baltimore his rights were still held by Mobile, which placed him on the suspended list. In 1921 his rights were transferred to Dunn’s Baltimore team.28 When Dunn sought to send Bates to Rocky Mount of the Virginia League, there was a paperwork issue, and Bates was threatened with a five-year suspension.29 While various parties wrangled over the suspension and whether it would be lifted, Bates played ball for semipro teams on the East Coast. He was reinstated for 1922.

The Rocky Mount Tar Heels of the Class-B Virginia League opened the season in 1922 with the 38-year-old center fielder batting third in their lineup. As the season progressed, Bates was moved to left field and switched to the leadoff spot.30 The season ended on September 6 and no statistics have been found to recognize Bates’ full season of work. He played briefly with Rocky Mount in 1923 before returning to his home in Steubenville.31

Bates took a job with a dairy in Steubenville which left his weekends free for baseball. Over the next decade and a half, he played and/or managed teams within 90 miles of his home. One thriving circuit with which he was involved was the Eastern Ohio League, which played on Sundays. In 1926 he guided the New Philadelphia Tuscoras to the championship series against Zanesville, but then was forced to miss the action because of his wife’s illness.32

While Bates traveled on the weekends, he also played locally in the Steubenville industrial league and with the town team. In 1925 he was pitted against pitcher Oscar Owens and the Homestead Grays with 2,500 local fans watching. Bates scored the first run of the game as the Steubenville team took the win, 3-0.33

Johnny Bates died of a heart attack in his home on February 10, 1949. He was buried in Steubenville’s Union Cemetery.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet were used for statistics and game stories unless otherwise noted. Ancestry.com was the source of family data.

Notes

1 “Superbas Make a Favorable Impression, Although Shut out in Opening Game,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 13, 1906: 14. Some contemporary newspapers spell the pitcher’s name McIntyre.

2 John H. Gruber,” Johnny Bates, One of Best Examples of Plugger Type of Ball Player, Never Star, but Always Dependable,” Pittsburg Post, April 4, 1906: 27.

3 “Bates Has Won Over Fans of Cincinnati,” Cincinnati Post,” April 11, 1911: 6.

4 “Bates Has Won Over Fans.”

5 A birth year of 1882 appears sometimes in connection with Bates. He listed the 1884 date on his Social Security application available on ancestry.com.

6 “Burgettstown Outplays Steubenville,” Pittsburg Post, September 18, 1904: 8.

7 “Altoona Signs an Outfielder,” Patriot (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), February 25, 1905: 6.

8 “Base Ball Briefs,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror, June 6, 1905: 3.

9 “Sharon Won Again,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 27, 1905: 10.

10 “Notes for the Fans,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times, February 12, 1906: 7.

11 “Bob Dunbar’s Sports Chat,” Boston Journal, May 2, 1906: 8. Note: “Bob Dunbar” was not a real person but the collective pseudonym used by the various Journal sportswriters wrote the column.

12 “No Cincinnati Game,” Boston Herald, August 6, 1907: 8.

13 “Crack Basketball Team to Visit New England,” Boston Journal, October 15, 1907: 9.

14 “National League,” Boston Journal, July 5, 1909: 8.

15 “Bowerman is Released,” Boston Herald, July 18, 1909: 5.

16 “Fogel Blocks Deal, with Cincinnati,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 26, 1910: 10.

17 “President Fogel Blocks Dooin’s Deal with the Reds,” Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, October 26, 1910: 12. It should be noted that different newspapers had different make-ups of the deal with various pitcher’s names mentioned. Some had it as a 3-for 3, others as a 4-for-4.

18 “Former Quaker Manager Says Reds Got None the Worst of the Deal,” Cincinnati Post, November 17, 1910: 6.

19 “Bates Out for Week,” Cincinnati Post, May 20, 1912: 6.

20 “Pink Slip for Bates,” Harrisburg Telegraph, January 23, 1915: 11.

21 Tim Patch, “It Strikes Me,” Richmond (Virginia) Times-Dispatch, May 9, 1915: 23.

22 “Dunnie Going to Raleigh,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 22, 1916: 9.

23 “Orioles in Nice Stride,” Baltimore Sun, May 3, 1916: 10.

24 “Tipple Fools Indians,” Baltimore Sun, July 28, 1916: 7.

25 Gruber, “Johnny Bates, One of Best Examples of Plugger Type of Ball Player.”

26 The Sporting News, June 27, 1918: 8.

27 “Bingoes Took Final Game,” Buffalo Times, August 9, 1918: 10.

28 Sporting News Contract Card File https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/22459/rec/57 Last accessed November 17, 2020.

29 “Johnny Bates Barred,” Chattanooga News, March 24, 1921: 8.

30 “Truckers Win,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, May 14, 1922: 49.

31 Gruber,” Johnny Bates, One of Best Examples of Plugger Type of Ball Player.” While Gruber is the convenient resource, all these teams can be substantiated by box scores from contemporary newspapers.

32 Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, September 20, 1926: 8.

33 “Steubenville Blanks Grays by 3-0 Score,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, August 3, 1925: 7.

Full Name

John William Bates

Born

August 21, 1882 at Steubenville, OH (USA)

Died

February 10, 1949 at Steubenville, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.