Bill Davidson

Bill Davidson – commonly known as “Davy” – was in the majors as an outfielder from the tail end of the 1909 season through 1911. His career was nothing spectacular, but there he was in “The Show,” in Cubs and Dodgers Blue (Superbas Blue, if you want to split hairs). His 1954 obituary in the Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal amounted to about two column-inches, and barely gave his major-league career two lines.1

But three days later, a newspaper in Fairbury, Nebraska, picked up where the Lincoln paper left off. A feature article detailed an extraordinary faceoff with the notorious Barker-Karpis Gang during an April 1933 bank robbery – an event that was the defining moment in the well-lived life of William Simpson Davidson.2

* * *

Davidson was born in Lafayette, Indiana, on May 10, 1884, to lawyer C. Joseph Davidson and his wife, Jeannie (née Scott). He grew up not far from the National League ballpark in Chicago. He and his older brother, Paul, played hooky and haunted the ballfield, climbing fences, chasing foul balls, and basically trying to be a help rather than a nuisance so the ballplayers wouldn’t chase them off. The two became steeped in ballplayer culture, so it was natural for both to find slots with local semipro clubs. When Paul embarked on a professional career, Davy wasn’t far behind. The young right-hander was approaching his full adult height of 5-feet-10 and a trim weight of 170 pounds.

Davidson was born in Lafayette, Indiana, on May 10, 1884, to lawyer C. Joseph Davidson and his wife, Jeannie (née Scott). He grew up not far from the National League ballpark in Chicago. He and his older brother, Paul, played hooky and haunted the ballfield, climbing fences, chasing foul balls, and basically trying to be a help rather than a nuisance so the ballplayers wouldn’t chase them off. The two became steeped in ballplayer culture, so it was natural for both to find slots with local semipro clubs. When Paul embarked on a professional career, Davy wasn’t far behind. The young right-hander was approaching his full adult height of 5-feet-10 and a trim weight of 170 pounds.

Bill Davidson played with Chicago’s well-regarded Hyde Park baseball team. He picked up experience at the University of Arizona, where he also played football and “studied some.”3 With those credentials he lassoed a spot in 1904 with an independent team in Clinton, Iowa, where a two-homer performance in a wet and muddy exhibition against Davenport of the Three-I League made news in papers across the state.4

One man who took notice was Frank Boyle, manager of the Fort Dodge Gypsumites of the Class D Iowa State League, who signed Davidson for 1905. In left field that season, he took care of business in often spectacular fashion, to the delight of local admirers.

Davidson displayed speed in the outfield and on the basepaths. Box-score totals show he swiped around 34 bases in his first year and had similar numbers consistently throughout his career. He ran with measured aggression; if an opposing catcher stood on the line when he was trying to score, he would take him down, and you could bet the ball would be kicked to the grandstand. You didn’t want to get on his bad side. Once, an umpire levied a $10 fine, and “Davidson, quick-tempered as usual, sought him out in the evening and told him to release the fine or he would throw him in the river. He promptly released the fine.”5

Hampered by little injuries, he struggled at the plate deep into the season. Then, on a hunch, manager Boyle plugged Davidson into the leadoff slot.6 That was just the challenge he needed, as his hitting improved the rest of the way. The Gypsumites, a fine team already, matched first place Ottumwa in wins.7 Unfortunately, they had three more losses, games that teams in those days clubs never bothered to make up. While Boyle’s team missed the pennant by a hair, he called Davidson his kid with “the brightest future, as he makes a study of the game, and is a natural born player.”8

In 1906 Davidson picked up where he had left off – and then some. He hit .337 in the month of May, then upped his batting average to .387 in June.9 In July he had to step down for a spell because of a boil on the bridge of his nose, “a great inconvenience”10 that almost closed both of his eyes. Davy later courted disaster when he got spiked in the leg and blood poisoning set in. Both times he convalesced quickly; he finished his season at .344 to far outpace the rest of the Iowa State League hitters.

Meanwhile, Davidson had been scouted by Ducky Holmes, manager of the Lincoln club in the Class A Western League, who briskly cornered Boyle and started negotiating. The Detroit Tigers had already offered $700 for the Fort Dodge outfielder, but with all kinds of strings. Holmes offered $500, no strings attached, and the deal was struck.11 With Lincoln, Davidson hit .339 in 16 games to close out the season.

In April 1907 Davidson started off his first full Western League season with a hitting flurry. Then, on a simple popup play, infielder Eddie Gagnier disregarded Davidson’s shouts and plowed into him.12 Gagnier got the worst of it, but right afterward Davidson’s batting average tumbled from .393 to .259 in a matter of weeks.13 His fielding didn’t suffer, and game reports were peppered with accounts of his fine catches and superb throws.

Davidson never recovered from the batting slump, and his season-ending .244 batting average, compared with the .300 expectations, was a disappointment. The next spring, he was moved to center, out of the “sun field” in left that “had much to do with dimming Davy’s lamps.”14 He still batted just about the same as the season before, though a resurgence in the final days bumped his average up to .259. The encouraging finish boded well.

Lincoln manager Bill Fox took Davidson aside in the spring of 1909 and, observing that he had been pulling his drives into left field, suggested a straightaway batting approach.15 It clicked: Davy flirted with the .300 mark for the entire year, finishing at .295 with 44 extra-base hits. Thus, he turned into the player who had been expected all along by his fans, his team, and himself.

Davidson was finally having fun again. At a hotel in Omaha, he called the bellboy over and excitedly told him to hurry to Bill Fox’s room because he urgently needed the key to the pitcher’s box. As the bellhop and head clerk hustled up the stairs, Davidson savored a good laugh.16 In August Paul Davidson hooked on with Omaha, and the brothers took the field against each other for the only time in their pro careers. Paul had failed a tryout with the St. Louis Browns a few years before and was now stringing out the back end of an eight-year minor-league career. It was the younger brother who would finally outpace the older.

On September 1, 1909, the Chicago Cubs drafted Davy Davidson from Lincoln, just beating out Brooklyn and Cincinnati.17 In his first appearance in a Chicago uniform, on September 29, he played errorless center field. “He caught everything in his territory except one Frank] Schulte took away from him, and at bat hit one safety too hot for Kitty] Bransfield to pinch.”18 Along with his first major-league hit, Davidson worked Philadelphia Phillies right-hander Lew Moren for a walk, stole second, and came home on Joe Tinker’s flare single to help seal a 6-3 Cubs win. His performance helped secure a complete-game victory for pitcher Ray Brown – whom I.E. Sanborn of the Chicago Tribune sarcastically dubbed “Four-Finger Brown” – in his lone major-league appearance.19

The Cubs were a juggernaut, giving Davidson little hope of breaking into their lineup of stars. Still, he was celebrated as a top prospect, and was highly regarded by manager Frank Chance. I.E. Sanborn wrote, “It will be a surprise if he lets Davidson get away.”20 Sanborn got his surprise when, a few weeks later, a deal was closed that sent “three recruits” – Davidson and two Smiths named Tony and Happy – to Brooklyn for pitcher Harry McIntire.

Meanwhile, Davidson had gotten a sense that the Cubs players weren’t all that much better than he was. “When I was traded to Brooklyn, I felt sure I could hold my own … and found a team I felt I could help. Many of us were starting in the big league together and felt closer to one another.”21 Things couldn’t have looked brighter for 1910.

Davy had some decent company on the Brooklyn Superbas. The club had future NL batting champ Jake Daubert at first base, a man deemed Hall of Fame-worthy by some. Silent John Hummel was holding down second base, while left-hander Nap Rucker was a solid starter. Most notable was Zack Wheat, who was entering the first full season of a marvelous Cooperstown career. Brooklyn was far from the team that would go to the World Series in 1916, but with Daubert and Wheat, the pieces were falling into place.

At the time, though, the Superbas were not much to crow about. For Davidson, that spelled opportunity. But cold spring weather wreaked havoc on his throwing arm. As the season unfolded, Davy warmed the bench, with only an occasional chance to pinch-hit or run. When he finally got his chance, he went 4-for-4 with two stolen bases and two runs scored in a 7-6 loss to Pittsburgh on May 9. A pair of multi-hit games followed shortly thereafter. No wonder Frank Chance didn’t want to give up on Davidson. He hit .350 during his first two weeks in the lineup, was over .300 through most of May, and a week into July was still batting a respectable .283.

Davidson’s play drew praise in the local press, with the Brooklyn Times observing: “One of the happy surprises in Brooklyn is the fine work of Davidson, who is playing center field for the team. … The moment that Davidson did break into the game he proved his cleverness so conclusively that he has been there ever since. … He plays baseball as if he likes it, and he looks like a star in the Brooklyn outfield for a long time to come.22

In July Davy slipped a gear, and the crash came fast, all the way down to .235 in just a matter of weeks. When he was benched on August 2, the Brooklyn Citizen called it “belated” and “a relief.”23 Just three days later, though, fellow outfielder Jack Dalton was hurt. “Frank] Betcher drove a foul fly to the outfield and Jack started after it. … The outfielder tore into the fence at top speed, striking his head violently and dropping to the ground senseless.”24 As Dalton was revived and assisted off the field, Davidson’s career was likewise resuscitated. In the second game of the doubleheader that day, he went 2-for-3 and got a second wind.

He couldn’t get back to that .300 form, but in fits and spurts his game improved. Gradually, Davidson’s stock began to rise. The Brooklyn Citizen praised his improvement, calling him one of the most valuable youngsters in the National League, “about the only man on [manager Bill] Dahlen’s team that shows championship class in getting around the bags.” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Davy’s most determined cheerleader, added, “This youngster is going to be a valuable man next year in the center garden.”25

The numbers didn’t back that up. Davidson hit .292 in 57 games that Brooklyn won, but only .199 in 78 games that the club lost. He finished the season batting .238 overall. He did lead the team with 27 stolen bases, but Brooklyn was next to last in the National League with 151 steals, less than half of Cincinnati’s 310. The modern WAR metric puts him at a negative for both his Brooklyn seasons. Still, his potential was undeniable, and Brooklyn re-signed him for 1911.

During the offseason, Davy finally felt ready to take on the duties of matrimony. On November 2, 1910, he took the hand of 23-year-old Nebraskan Jennie Blanche Scott (known to most as Jane) and settled into her hometown of Lincoln. They were matched for life.

The next spring brought Davidson to his first training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and wacky Whittington Park, a baseball hazard with an obstacle course in the outfield that included several ditches, a pipe drain, and a creek. Two of his fellow outfielders were hurt chasing balls into the wilds, while Davidson himself narrowly escaped injury several times, spilling down the creek banks. He survived to hit .328 during the preseason26 and looked, according to the Brooklyn Citizen, “like the real candy kid.”27

What could have been a breakout season for Davidson was instead a disheartening rerun of the year before, as his batting average descended to .149 by late June. He was platooned with left-handed batter Al Burch, and for much of the time he was just plain benched. Davidson coached at third when requested, but often as not was a detriment. One time he waved baserunner Jake Daubert home on a double, then changed his mind when he saw the terrific throw coming in from the outfield. He chased Daubert down the line, grabbed him by the waist halfway to home plate, and tried to wrestle him back to third base. Daubert was, of course, tagged out.28

The more Davidson struggled, the harder it got, as he later explained to an Omaha newspaper reporter: “The public out here doesn’t understand the spirit that some of the fans have in the big cities. They roast the home team unmercifully, and the out-of-town men have to be on guard continually, both on and off the field. Brooklyn is about the worst of any of them. I only took my wife to a couple of games while I was there. The bleacher crowds are profane to the limit, and sometimes the grandstand is worse. They call a player anything they may happen to think of, and the police pay no attention to them. Just over the outfield fence in Brooklyn is a row of ‘Dago’ flats. A bunch of roughnecks stick around in the windows and on the roof and throw rocks at the outfielders. The outfield used to be chuck full of junk that had been thrown over the fence at players. I used to be afraid some of them would get back in a window and take a shot at me.”29

Though the Brooklyn Daily Eagle sniped that his batting average needed to be viewed with a microscope,30 Davidson finally started getting some playing time. He worked his average up to .239 but was hampered by a sore arm. He had one memorable game on August 5 against his former team, the Chicago Cubs, going 4-for-4 with a triple and three RBIs. A week later, he hit his only major-league home run, a three-run shot off Braves right-hander Orlie Weaver in an 8-6 road victory over Boston. Then on September 21, he was paid in full by the club, tendered a contract for 1912, and sent to Youngstown, Ohio, to see the renowned therapist John “Bonesetter” Reese about his ailing arm.31 Brooklyn was serious about getting Davidson healthy for the following year but already had a replacement in mind, if needed. Hub Northen had hit .316 in the final 19 games of the 1911 season and would take over the outfield slot in 1912.

When he arrived in Hot Springs in spring 1912, Davidson couldn’t be faulted for thinking that a third year in Brooklyn, as it had been in Lincoln, could be his good-luck charm. To amplify the luck, he and a teammate made a merry excursion to the alligator farm just outside of Whittington Park. Tagging along was Charles “Victory” Faust, the New York Giants’ mascot and good-luck charm of 1911. Faust may have been good for a laugh, but hanging out with him may not have been the best choice of company.

In any event, Davidson’s luck had run out. He worked diligently, executed daily marathon runs, and trained with the great Wee Willie Keeler in the fine art of the bunt.32 He did everything the team asked of him, but on the eve of the new season, he was bound not for Brooklyn but for Omaha. He had been sold outright, back to the Western League.33

It was a shock to be back in the bushes. However, Jane was surely pleased to have her husband close to home again; plus, she could now expect to be treated in a civil Midwestern manner in the grandstand. The Omaha Daily News reported on seven wives who regularly attended their husbands’ games, and in a photo taken at the ballpark, Jane smiles tolerantly.34

Davidson took a while to get into the groove but pulled himself up to .240 by the end of May.35 Then, as the Omahas chugged off for a road trip, he was surprised to find himself left behind. Omaha owner Pa Rourke claimed that Davy had been in poor condition all season – indeed, the Omaha Evening World-Herald called him “Bill Taft Davidson,” a not-so-subtle allusion to the rotund president.36 Rourke unsuccessfully lobbied the National Commission to require Brooklyn to refund him the price that he had paid for “damaged goods.” With this kind of bad press, Davidson could find no work the rest of the summer after Omaha released him.37

As the 1913 season approached, Davidson’s former manager Ducky Holmes was at the reins of the Western League’s Sioux City Packers and anxious to give his favorite outfielder a fresh start. Davidson arrived at camp in Tulsa “chipper as a kitten.”38 He was determined to do well and get revenge on Pa Rourke. Opening Day put the Packers up against the Omahogs, and right away Davidson obtained some vengeance, going 4-for-5 against his old team. A big cluster of friends filling a section of the grandstand roared like madmen. Davidson himself roared all season, exploding for his first .300 campaign since the Fort Dodge days. But despite the fine play of Davidson and big-league-bound teammates Art Nehf and George Burns, Sioux City finished tied for sixth place.

By then having obtained an interest in a fine billiard parlor in Lincoln, Davidson felt he could safely wrangle for a higher salary. Many players were using the newly arrived Federal League as a “holdout threat” in contract negotiations. Davidson “averred he was not a member of the ‘holdout league,’ but just sorter wanted a little boost in recognition of his services last season.”39 Sure enough, Davidson started 1914 with a signed (and upgraded) contract from Sioux City in hand.

Then, just as his season was getting into gear, he suffered a near-calamity in Denver. As reported in the Sioux City Journal: “In the third inning … Bill Davidson made a running dive and crashed into the sides of the stand. His chin was ripped wide open, the skin being cut off the bone for the width of his face. He was removed to the hospital, where it was found necessary to take several stitches. The crash knocked him unconscious and his escape from a fractured skull was a narrow one.”40

Davidson’s injuries (including four front teeth knocked out) were dubbed “painful rather than serious.”41 Nonetheless, they laid him up for a full month. When he got back into the lineup, he returned with renewed passion. Davy slapped two singles and stole second twice against Denver in his first game, then racked up four hits against Lincoln.42

As he sailed through the summer, so did his team. Sioux City simply swamped the circuit and took the Western League pennant by 10½ games over perennial powerhouse Denver. Davidson hit a respectable .286, and also laid down a remarkable 75 sacrifices. (For comparison, the major-league record is 67 by Ray Chapman in 1917.) He could celebrate his only pennant, but injuries were adding up and Davy was looking at the tail end of his career. The following spring, he could barely secure an Opening Day roster spot, and at midseason his batting average was mired at .233. When Sioux City released him in August, it was by mutual agreement.

Having made it to the top of the heap, Davidson saw no point in playing out an ever-fraying minor-league string. He started out selling insurance, then landed a position as a traveling salesman for the Gillen & Bonny Candy Company of Fairbury, where the Davidsons had resettled. After hawking sugary confections around Nebraska for 15 years, he took his sweet tooth to a downtown lunchstand, which he operated until a more substantial offer came along.

At the close of 1932, Davidson was appointed Jefferson County’s deputy sheriff. Other than being a crack rifleman, he had scarce qualification for the position, but he leapt right into the challenge. Right off the bat, he was a righteous peacekeeper, his defense of local law being on a par with his defense of the outfield back in Brooklyn’s old Washington Park.

He was the ideal man at the right moment when, on April 6, 1933, a large, black Buick rumbled into Fairbury containing seven men, a veritable all-star team of veteran bank robbers. Within minutes of them storming into the First National Bank and shouting, “This is a holdup!” the phone rang in the office of the deputy sheriff, and Davy Davidson raced into the daylight and the defining moment of his life.

Click here to read more about “Bill Davidson vs. the Barker-Karpis Gang.”

* * *

After this heroic shootout – which was like something out of a Sam Peckinpah film – Davidson held his post for another six years. In 1939, at the age of 55, he stepped down to return to the mellower life of an insurance man. Later, he took charge of the Uptown Tavern, pouring cold ones for the neighborhood folks for many years. In 1942 he served as a bridge guard. One dark night, he was hit by a car while trying to untangle a wrecked truck at one end of the Platte River Bridge in Plattsmouth. He sustained a broken leg, yet it hardly slowed him down.

He and Jane ultimately returned to Lincoln, where he worked for the State Department of Roads and Irrigation. And it was in Lincoln where, at the age of 70, the man known to all as Davy died on May 23, 1954. (Jane survived him until 1963.) He was laid to rest in Rosehill Cemetery in Waverly, a village just to the northeast of Lincoln.

There was always a might-have-been in Davidson’s baseball life: the third Brooklyn season that never was. Yet, Davy Davidson had a life well-lived, in and out of the game, including a good measure of glory on the field – and one shining moment on the streets of Fairbury, Nebraska, which lives in legend.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb, Rory Costello, and Len Levin, and fact-checked by Tim Herlich.

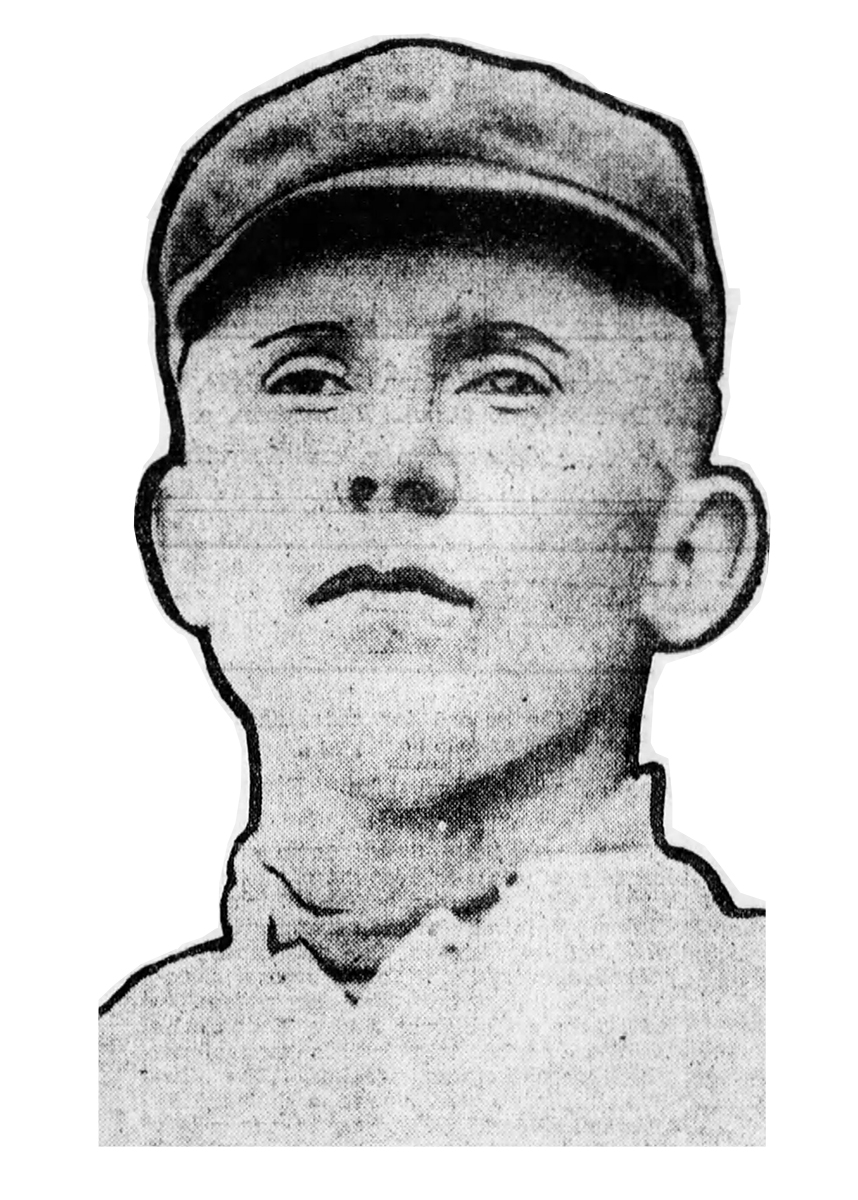

Photo credit: Bill Davidson, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 5, 1911.

Notes

1 Lincoln (Nebraska) Evening Journal, May 24, 1954: 2.

2 Fairbury (Nebraska) Journal, May 27, 1954: 1.

3 “Bill Davidson of the Superbas Tells How He Got His Start,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 3, 1910: 20. This is a nice feature that was carried by wire services to papers across the country, jam-packed with life details, though the sportswriter took lavish literary liberties. As papers picked up the item, they often added additional information of local interest, as did the Joliet Herald-News on September 11, 1910, when they discussed his time with Joliet High School and Hyde Park.

4 “Leaguers Defeated. Clinton Independents Put to Shame Davenport Leaguers,” Clinton Morning Age, June 25, 1904.

5 “Food for the Fans,” Fort Dodge (Iowa) Messenger, July 10, 1906: 8.

6 “Ottumwa Won the Odd Game,” Fort Dodge Daily Chronicle, July 31, 1905: 8.

7 Confusion is rife when it comes to team records in the Iowa State League. According to The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 3rd ed., Ottumwa had 74 wins to Fort Dodge’s 73; both the Reach and Spalding Guides of 1906 credit the two teams with 73, which also aligns with the daily line scores.

8 “Food for the Fans,” Fort Dodge Messenger, March 27, 1906: 8.

9 “Team Improves Batting Averages,” Fort Dodge Messenger, June 2, 1906: 1; “Iowa League Figures,” Fort Dodge Messenger, July 10, 1906: 8.

10 “The Sick Roll,” Fort Dodge Messenger, July 14, 1906: 3.

11 “In the Realm of Baseball,” Lincoln Evening News, July 23, 1906: 12.

12 “Last Game to Grizzlies,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), May 3, 1907: 3.

13 “Gossip of the Western League,” Nebraska State Journal, April 28, 1907: 23; “Gossip of the Western League,” Nebraska State Journal, June 2, 1907: 27.

14 “Buys Catcher,” Lincoln Evening News, March 14, 1908: 5.

15 “Diamond Gossip,” Lincoln Evening News, May 3, 1909: 6.

16 “Short Sporting Stories,” Lincoln Daily Star, May 2, 1909: 8.

17 “Diamond Gossip,” Lincoln Evening News, September 2, 1909: 6; “Return Today from Trip,” Nebraska State Journal, September 2, 1909: 6.

18 “Cubs Annex Two Jigtime Battles,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1909: 8.

19 “Cubs Annex Two Jigtime Battles.” Paul Percival Brown, “who stepped on to the slab with hardly the ghost of a reputation,” was reported to have made the jump from Minneapolis semipro ball right into a major-league uniform. Somewhere along the line, he picked up the nickname of Ray.

20 “Rally in the 9th Gives Cubs Game,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, March 13, 1910: Part III, 2.

21 “Bill Davidson of the Superbas Tells How He Got His Start.”

22 “Superbas in Final Clash with Pirates,” Brooklyn Times, June 4, 1910: 8.

23 “Superbas Prove That They Can ‘Come Back,’” Brooklyn Citizen, August 3, 1910: 6.

24 “Five Straight Victories Over the St. Louis Team,” Brooklyn Times, August 6, 1910: 8.

25 “Gossip of the Diamond,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 6, 1910: 20.

26 “Cold Weather Again Prevents Superbas Playing a Game,” Brooklyn Citizen, April 9, 1911: 5.

27 “Notes from Camp Superba,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 21, 1911: 4.

28 “Poor Battery Work Put the Superbas Out of the Running,” Brooklyn Citizen, June 25, 1911: 5; “Crazy Throws Do More to Beat Dodgers Than Matty’s Curves,” Brooklyn Standard Union, June 25, 1911: 6.

29 “Rourke Players Tell of Rooters’ Rowdyism,” Omaha Daily News, May 22, 1912: 9.

30 “Hoggish Giants Take Two More Ball Games,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 28, 1911: 23.

31 “Dodgers Paid Off and Permitted to Go Home,” Brooklyn Daily Times, September 21, 1911: 1.

32 William J. Granger, “Dahlen Has a Phenom in Kent, Says Erwin,” Brooklyn Citizen, March 17, 1912: 5.

33 “Bill Davidson Goes to the Omaha Club,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 17, 1912: Picture and Sporting Section, 2.

34 “Here Is a Group of Rourke Fans Who Are Personally Interested in Game,” Omaha Daily News, May 19, 1912: 2E.

35 “Thomason In Second Place,” Omaha Sunday Bee, June 2, 1912: S-4.

36 “Pa’s Sterlings Lose to Sioux City Again,” Omaha Evening World-Herald, April 23, 1912: 8.

37 “Paul [sic] Davidson Is Released by Rourke,” Omaha Daily News, July 27, 1912: 8.

38 “Sports,” Lincoln Daily News, April 10, 1913: 6.

39 “Sporting Briefs,” Sioux City Journal, January 31, 1914: 10.

40 “Davidson Breaks His Jaw in Fifteen-Inning Game at Denver,” Sioux City Journal, June 1, 1914: 3.

41 “Sports,” Lincoln Daily News, June 8, 1914: 3.

42 “Sioux Slaughter Ehman,” Sioux City Journal, July 13, 1914: 3.

Full Name

William Simpson Davidson

Born

May 10, 1884 at Lafayette, IN (USA)

Died

May 23, 1954 at Lincoln, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.