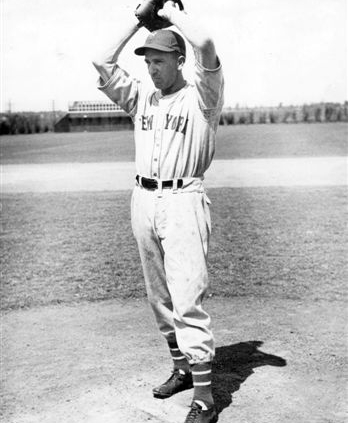

Carl Hubbell

Carl Owen Hubbell, one of the top pitchers of the 1930s, is rated one of the greatest pitchers in the game’s history. Born in Carthage, Missouri, on June 22, 1903, he spent his early years on a pecan farm near the small community of Meeker, Oklahoma. After his graduation from Meeker High School, Hubbell went to work for an oil company.

Carl Owen Hubbell, one of the top pitchers of the 1930s, is rated one of the greatest pitchers in the game’s history. Born in Carthage, Missouri, on June 22, 1903, he spent his early years on a pecan farm near the small community of Meeker, Oklahoma. After his graduation from Meeker High School, Hubbell went to work for an oil company.

Hubbell pitched for his high-school team, exhibiting a decent fastball and curve but not yet utilizing his yet-to-be-developed screwball pitch. After his graduation, followed by employment with an oil company, he started his organized-baseball career in 1923 with Cushing of the Oklahoma State League. In 1925, at 22, the lefthander had a 17-13 season with Oklahoma City of the Western League. By this time, Hubbell’s reverse-curve screwball was part of his pitching repertoire. He had come upon the pitch in attempting to turn the ball over in order to make it sink.

The Detroit Tigers purchased his contract from Oklahoma City after the 1925 season. But Hubbell suffered a bitter disappointment in his first major-league training camp in 1926 when Tigers player-manager Ty Cobb strongly urged him to discard the pitch because of the arm ailments other screwball throwers had experienced. (Interestingly, Christy Mathewson’s famous reverse curve “fadeaway” apparently did not injure his pitching arm). Forbidden to throw his screwball, Hubbell lost his effectiveness and, apparently, his confidence. Cobb did not play him during the exhibition season and Hubbell was sent to Toronto where he was instructed not to throw his screwball. He had a mediocre 7-7 year at Toronto and he was demoted again, this time to Decatur, Ill., in the Three-I League. Despite a 14-7 season with Decatur in 1927, the Tigers gave up on him, selling him to Beaumont of the Texas League.

Hubbell had not thrown a screwball for two years, but Beaumont manager Claude Robertson, a former catcher who realized the potential of the screwball, had no objection to Hubbell’s using the pitch. Hubbell lost several games while readjusting to its use but he finally managed to fully control the screwball, delivering it consistently low in the strike zone where it was most effective. Hubbell began to win and baseball men took notice. He had 12 victories by midseason.

New York Giants manager John McGraw learned of Hubbell’s new-found prowess through Dick Kinsella, one of his scouts. Kinsella was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in Houston that year. He took time off from the convention to take in a Texas League game. He saw a superb extra-inning pitching duel between Hubbell and Houston lefty Bill Hallahan. Hubbell lost the game in 11 innings but that night, Kinsella called McGraw and told him about the 25-year-old screwballer. McGraw paid Beaumont $30,000 for Hubbell’s contract and the future Hall of Famer reported to the Giants in midsummer of 1928.

In his first start, on July 26, Hubbell lasted less than two innings against the Pirates, losing 7-5 at the Polo Grounds. Encouraged by McGraw, Hubbell won his first major-league game five days later after he relieved Freddy Fitzsimmons in the ninth inning against the Cubs and the Giants, losing 7-3, pulled out a win. Hubbell had his breakthrough effort in St. Louis two weeks later, relieving in the third inning and holding the Cardinals at bay before losing to them in the 15th inning. In his Super Stars of Baseball, St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg wrote that Hubbell threw his first screwball in the majors in that long effort. As Broeg described it: “When slugging [right-handed-hitting outfielder] Chick Hafey came to bat with the winning runs on base and the count (at 3-and-1), Hubbell broke off a screwie. Hafey swung and missed. Again, came the fadeaway. Again, Hafey, not expecting the ball to break down and away, swung and struck out.” Giants catcher Frank “Shanty” Hogan advised Hubbell to keep throwing the pitch, which became his money pitch for the next 15 seasons.

Hubbell finished the season 10-6 with a solid 2.83 E.R.A. He was a well-established starter over the next four seasons, with an overall 67-46 record. His most notable achievement during that period came on May 8, 1929, when he pitched an 11-0 no-hitter against the Pirates at the Polo Grounds. Hubbell’s only difficult inning came with none out in the ninth when two Giants errors left two Pirates on base. Hubbell struck out Lloyd Waner and started a game-ending double play on Paul Waner’s smash back to the box. Hubbell’s good friend and longtime collaborator, Mel Ott, supported him with two home runs.

The Giants played adequately during Hubbell’s first full seasons with the club, 1929 through 1932, but these were frustrating, tension-packed, years under the ill, emotionally exhausted John McGraw. His Giants teams had won 10 pennants and three World Series and finished in first or second place in 21 of his 29 full seasons. But the Giants had not won a pennant since 1924, and the irritable McGraw had aged prematurely. And so, Hubbell and his teammates were relieved when Bill Terry replaced McGraw on June 3, 1932. Terry took over a last-place team and led it to a sixth-place finish. Hubbell pitched well under both managers that season, with an 18-11 record and a 2.50 ERA.

Terry bolstered his club during the offseason, most importantly by acquiring skillful catcher Gus Mancuso from the Cardinals. Mancuso was especially adept in handling low pitches to gain strike calls. Terry, an accomplished defensive strategist, was aided by a new National League plan to use a deadened baseball in 1933, thereby making defense a more important element in winning games.

In a preseason AP poll, the low-rated Giants were picked to finish sixth in the eight-team National League. The Giants were moderately successful early in the season, in third place on Memorial Day. Hubbell pitched superbly as the Giants won a series of low-scoring games and took over first place on June 10, as Hubbell, knuckleballer Freddy Fitzsimmons, sinkerball-throwing Hal Schumacher, and fastballer Roy Parmelee rounded out the starting staff. Hubbell, the only left-hander on the staff, also excelled in relief. By July Fourth, the Giants led the league by five games.

Hubbell gave a memorable performance on July 2, as he threw 18 scoreless innings and allowed only six hits in defeating the Cardinals, 1-0, at the Polo Grounds. He pitched perfect ball in 12 of the innings, and struck out 12 batters without issuing a walk. Now referred to as the Giants’ Meal Ticket, Hubbell continued to win complete games and save games in relief, setting a record (since surpassed) of 45 consecutive scoreless innings on August 1.

Hubbell turned in one more masterpiece in September as the Giants closed in to clinch the pennant. His control was impeccable in a 2-0, 10-inning victory over the Boston Braves. Journalist Heywood Broun, watching from the press box, marveled at Hubbell’s efficiency. He walked just one batter. “Such control in a lefthander is incredible,” wrote Broun. “There must be a skeleton in Hubbell’s closet somewhere, perhaps a righthanded grandmother.” Skeleton or not, Hubbell had a 23-12 record with a remarkable 1.66 ERA and 10 shutouts, earning the National League MVP award.

The Giants defeated the Washington Senators, led by shortstop-manager Joe Cronin, in a five-game World Series. In the first game, Hubbell struck out the side in the first inning, setting the pace for a 4-2 win. It was a typical Giants win in that season as Hubbell pitched superbly, the Giants played sound defense, and Mel Ott led the offense with a two-run homer. With the Giants leading the Series two games to one, Hubbell won the fourth game, a 2-1, 11-inning affair. Hubbell was not needed as the Giants clinched the Series the following day.

The Giants led during most of the 1934 season before slumping badly over the final weekend of the season, edged out by the Gas House Gang-led St. Louis Cardinals. The season is best remembered for Hubbell’s historic achievement in the All-Star Game, when he struck out five straight future Hall of Famers, none of them familiar with the screwball. With two American Leaguers on base in the first inning at the Polo Grounds, Hubbell struck out Babe Ruth with three consecutive screwballs. Lou Gehrig took a ball and then swung through three more screwballs. Jimmie Foxx distinguished himself by comparison, at least managing one foul tip in the process of striking out. With the fans still buzzing, Hubbell struck out Al Simmons and Joe Cronin, the first two hitters in the second inning, before allowing a single to Bill Dickey.

The next season, 1935, was another disappointing year for Hubbell and his teammates. After leading the league all season through late August, the Giants fell back as the Cubs won 21 straight to take the pennant. The losses in 1934 and 1935 came despite Hubbell’s continuing effectiveness. In effect, he duplicated his brilliant 1933 performance, winning 21 and 23 games the next two years with excellent ERAs considering the livelier ball used after 1933.

Hubbell had what many considered his best season in 1936 as the Giants won the pennant after falling as low as fifth place in mid-July. He won a career-high 26 games, winning the MVP for the second time, in leading the Giants in a remarkable comeback. Hubbell won his last 16 decisions of the season and led all National League pitchers in wins, winning percentage, and ERA. Hubbell’s true value was best reflected by his ability to win the important games and to supply stability to the pitching staff when the older pitchers slumped and the younger pitchers foundered.

In the World Series, the Giants took on the powerful Yankees, who were led by Lou Gehrig, Bill Dickey, and rookie Joe DiMaggio. Hubbell won the rain-soaked opener, 6-1, controlling the heavy-hitting Yankees until the Giants clinched the game with four runs in the eighth inning. But subsequently, Hubbell was unable to hold off the Yankees, as he lost his second start of the Series, his first loss since July. The Giants lost the Series in six games.

The 1937 season closely resembled the previous season. The Giants were seven games behind the first-place Cubs in early August before rebounding to win the pennant. Hubbell continued his winning streak, winning his first eight decisions. The streak came to an end in a Memorial Day doubleheader at the Polo Grounds when the second largest crowd in the ballpark’s history, 61,756, watched as Hubbell was routed by the Dodgers in the fourth inning after retiring only one batter. Between games of the doubleheader, Hubbell was presented his 1936 MVP award by Babe Ruth. Hubbell’s last win of the season clinched the pennant. He produced another brilliant year, leading the league in wins and strikeouts. The World Series was virtually a duplicate of the 1936 Series. The overpowering Yankees had the same collection of stars as in the previous season, and the only Giants win came when Hubbell won the fourth game, 7-3.

Over the five-year period from 1933 to 1937, Hubbell’s pitching excellence had been largely instrumental in bringing the Giants three pennants and a World Series victory. But these triumphs came at a price. In throwing a standard curveball, a left-handed pitcher twists his wrists to the left in a counter-clockwise motion, with the pitch breaking in to a left-handed batter. Hubbell’s screwball forced him to defy nature by twisting his wrist to the right, causing the pitch to break down and to the left, away from the right-handed batter. Thrown properly, Hubbell’s signature pitch confounded the hitters but also resulted in considerable strain on his left elbow. Hubbell later admitted that the pitch had begun to hurt his elbow as early as 1934 and that by 1938, his pain had become unbearable..

The Giants led the league through midseason of 1938 but slipped out of contention in mid-August. On August 18, while pitching in a 5-3 loss to the Dodgers, Hubbell had to leave the game with a painful elbow. A few days later he had a bone chip removed and his 13-10 season was over. The Giants, a different team after the loss of Hubbell, finished in third place.

Hubbell came back to pitch for five more seasons but he was little more than a .500 pitcher until his retirement after the 1943 season. Still, he showed flashes of his former brilliance. On Memorial Day in 1940, he pitched a near no-hitter, holding the Dodgers to one hit and, after the only baserunner was erased in a double play, faced the 27-batter minimum. Hubbell won eight straight games in 1942, and on June 5, 1943, he pitched his final masterpiece, a brilliant one-hitter against the Pirates. Hubbell retired after that season with a career 253-154 record. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in1947.

Years later, Hubbell explained the screwball’s deceptiveness, especially to hitters unfamiliar with the pitch. “What made the screwball so successful was throwing it over the top with exactly the same motion as a fastball,” he told a writer. “If a hitter is ready for a fastball, he can adjust to the breaking ball. But with a screwball, it isn’t the break that fools the hitter, it’s the change of speed. They couldn’t time it and were out in front of it.”

The fans as well as the players marveled at Hubbell’s mastery of the pitching craft, much as the fans of a later era admired Greg Maddux’s performance, demeanor, and style. A knowledgeable Giants fan, who had watched the club from a Polo Grounds bleacher seat from the early 1920s through Hubbell’s entire career, described Hubbell in Fred Stein’s Under Coogan’s Bluff:

“When most people talk about Hubbell they usually have in mind his screwball, his 18-inning masterpiece … in 1933, his 1934 All-Star Game strikeout feat. … I don’t think of his individual games. I think of an artist painting a portrait, every stroke of the brush with a purpose. … Hub would start a batter off with a curve and it was usually a beaut, always low and on the corner of the plate. Then, with that uncanny control and that good speed of his, he’d bust one in, either on the fists or high and outside. Then maybe a changeup. Next, the screwball. Jeez, what a pitch! It gave those righthand hitters fits, especially after Hub set them up with the curve and the fastball. …

“Hub was great in the clutch. He won for years with a low-scoring team and he won the big games consistently. Also, he won more than he lost against the great pitchers of his time–(for example, winning 8 of 11 times against Dizzy Dean). He also had winning margins against Lon Warneke, Paul Derringer, and other great pitchers in his era. His only weakness was that the Dodgers were his jinx team and that was rough, the Giant-Dodger rivalry being what it is.

“Hubbell had the perfect temperament. He never got excited or lost his concentration when we blew an easy chance behind him. And I used to get a kick just watching him in the dugout on days he wasn’t pitching. Even at the end of his career when he’d seen it all, he would sit there quietly and never take his eyes off the batter or the pitcher. I think he knew their strengths and weaknesses better than they did themselves. All in all, Hub was the greatest left-hander I’ve ever seen and most of the players I know feel the same.”

Hubbell’s fellow players were equally in awe of the left-hander. Hall of Fame righthander Waite Hoyt provided an insightful analysis of Hubbell’s consummate skill, commenting: “Hubbell is one of the great pitchers, yet he presents no mystery to the onlooker. The source of his skill is his matchless control in using his curveball to set up his screwball. Emotions, if he has any, never affect him. His timing, his conservation of energy, and influence on the ballclub are other factors in rating him among the great pitchers of all time.”

The media nicknamed Hubbell King Carl, Old Long Pants, or Meal Ticket. Bob Broeg described him as “awkwardly angular, gaunt, lean-visaged, and almost Lincolnesque in appearance, (with) … no hips, less derriere, and the longest shinbones in captivity.” Years of throwing his screwball left him with a deformed left hand with the palm facing out instead of in against his body. He was a quiet, undemonstrative, thoughtful man, with a wry sense of humor.

Hubbell married his high-school sweetheart, Lucille Herrington of Shawnee, Oklahoma, when he was 27. The couple had two sons, one a career Marine and the other a businessman. Years after the death of Mrs. Hubbell, Hubbell married Julia Stanfield of Casa Grande, Arizona.

Mel Ott replaced Bill Terry as the Giants’ manager in 1942 and Terry moved into the front office to run the club’s farm system. Hubbell replaced Terry as farm director in 1944 and continued in the position while the Giants remained in New York through the 1957 season, and later after the Giants moved to San Francisco. He remained in the same job until he suffered a stroke in 1977. Hubbell was a part-time scout for the Giants for the next 11 years. He died in Scottsdale, Arizona, at the age of 85, on November 21, 1988, after an automobile accident, coincidentally just 30 years to the day after the death of his close friend Mel Ott, who died as the result of a similar accident.

Sources

Interview with Carl Hubbell, Washington, D.C. 1984

Bob Broeg. Super Stars of Baseball. St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1971.

Frank Graham. McGraw of the Giants. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1944.

Fred Stein. Under Coogan’s Bluff. N.P.: Chapter and Cask, 1979.

Total Baseball 7th Edition. Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 2001.

Peter Williams. When The Giants Were Giants. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994.

Full Name

Carl Owen Hubbell

Born

June 22, 1903 at Carthage, MO (USA)

Died

November 21, 1988 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.