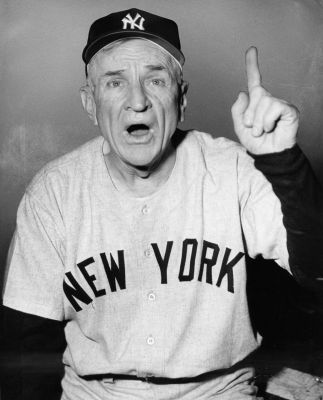

Casey Stengel

Casey Stengel is best remembered for his managerial accomplishments with the juggernaut New York Yankees of the 1950s and the bumbling, beloved New York Mets of the early ’60s, but decades earlier he was a hard-hitting outfielder who compiled a .284 batting average over 14 seasons in the National League. Planting his right foot closer to the plate than his left, as if he were peering at the pitcher over his right shoulder, the left-handed Stengel held his hands down at the end of the bat and took a healthy swing. He hit more long balls than most Deadball Era players, but it also made him more susceptible to change-ups and curves. Perhaps the strongest aspect of his game was his defense; he excelled at playing the sun field, and the long hours he spent practicing caroms off the fences at Ebbets Field paid off when he led all NL outfielders in assists in 1917.

Casey Stengel is best remembered for his managerial accomplishments with the juggernaut New York Yankees of the 1950s and the bumbling, beloved New York Mets of the early ’60s, but decades earlier he was a hard-hitting outfielder who compiled a .284 batting average over 14 seasons in the National League. Planting his right foot closer to the plate than his left, as if he were peering at the pitcher over his right shoulder, the left-handed Stengel held his hands down at the end of the bat and took a healthy swing. He hit more long balls than most Deadball Era players, but it also made him more susceptible to change-ups and curves. Perhaps the strongest aspect of his game was his defense; he excelled at playing the sun field, and the long hours he spent practicing caroms off the fences at Ebbets Field paid off when he led all NL outfielders in assists in 1917.

Descended from German and Irish immigrants, Charles Dillon Stengel was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on July 30, 1890. His father made a steady living selling insurance and Charley had an enjoyable childhood, much of it spent playing sandlot baseball. He was a star athlete at Central High School, leading the basketball team to the city championship and pitching the baseball team to the state championship. In 1910 Charley signed with the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, perhaps the fastest minor league of the time. His pitching skills weren’t up to the level of AA competition, however, so manager Danny Shay moved him to the outfield. To give him some seasoning, Kansas City optioned Stengel to the Class C team in Kankakee, Illinois, where he batted .251 before the Northern Association folded in July. For the rest of the season he hit .221 in the Class D Blue Grass League.

When the season ended, Charley followed his friend Billy Brummage to the Western Dental College in Kansas City. Having an alternative career as a dentist enabled him to negotiate a raise for the 1911 season. The Blues assigned him to the Class C team in Aurora, Illinois, where he led the Wisconsin-Illinois League with a .352 average. Brooklyn’s premier scout, Larry Sutton, liked what he saw in Stengel. The Superbas bought him in the August draft and assigned him to Montgomery of the Southern Association for 1912.

At Montgomery Stengel came under the tutelage of Kid Elberfeld, a veteran major leaguer who schooled the 21-year-old outfielder in place hitting and other tactics of the inside game. Charley started developing his reputation for eccentricity in the Southern Association. Senators scout Mike Kahoe called him a “dandy ballplayer, but it’s all from the neck down.” In one game he hid in a shallow hole in the outfield, covered by a lid; peeking out from under the lid, he suddenly popped out of the hole just in time to catch a fly ball that came his way. Stengel also took care of business, hitting .290 and leading the league in outfield assists. Brooklyn summoned him to the majors when the Southern Association season ended.

Stengel made an auspicious major-league debut on September 17, 1912. Starting in center field, he singled four straight times, drew a walk, drove in two runs, and stole two bases as the Superbas beat the Pirates, 7-3. The next day Charley joined a poker game as the players waited out a rain delay. When he finally won a hand, one of his teammates said, “About time you took a pot, Kansas City.” The other players caught on, calling the rookie “K.C.” After one week in the big leagues, Stengel had a nickname, a .478 batting average, nine RBIs, and a tremendous home run to right field that was said to be the longest hit in Brooklyn all season. Though he eventually cooled off, Casey still ended the season with a .316 batting average in 17 games.

Stengel held out until March 13, 1913, before Charles Ebbets finally sent him a contract that he found satisfactory. It didn’t take Casey long to round into form. In an exhibition game against the Yankees on April 5, he became the first Brooklyn player to bat at Ebbets Field, and five innings later he hit the first home run at the park. A few weeks later Casey also hit the first regular-season home run. Suffering from a sprained ankle and a sore left shoulder that hindered his throwing, Stengel proved streaky and briefly lost his starting job to Bill Collins. He reclaimed center field by season’s end, however, and finished the year at .272 with seven home runs and a career-high 19 stolen bases.

With newspapers reporting that the Federal League’s Kansas City franchise was interested in the hometown star, Ebbets offered Stengel a three-year contract at almost double his previous salary. Casey opted for a one-year deal instead, believing that he would have more bargaining power if he stayed healthy in 1914. In January he went to Mississippi to rehabilitate his sore shoulder and assist his old Central High coach, William Driver, who was coaching baseball at the University of Mississippi. (That is how Casey originally came to be called “Professor.”) Brooklyn’s new manager, Wilbert Robinson, moved Stengel to right field and eventually platooned him, first with Joe Riggert and later with Hy Myers. Playing primarily against right-handed pitching, Casey improved his average to .316 and led the NL with a .404 on-base percentage. The Robins rewarded him with a two-year contract and a substantial raise.

Stengel reported to training camp in March 1915 at 157 pounds, 20 pounds below his usual playing weight. The official explanation was typhoid fever, but sportswriters later hinted that it was actually a venereal disease. Casey was in the starting lineup on Opening Day, but was still weak. His batting average dipped as low as the .150s before he finally broke out of his slump in July to finish at .237, the lowest average of his career. He rebounded in 1916, and teammate Chief Meyers in The Glory of Their Times said Stengel deserved credit for Brooklyn winning the pennant. In a late-season showdown with the second-place Phillies, Stengel homered off Pete Alexander to lead Brooklyn to victory. Platooned with Jimmy Johnston in right field, Casey ranked third on the club in batting average (.279), runs scored (66), and RBIs (53) and led Brooklyn with a .364 average during the World Series.

Despite his and the team’s success, Stengel found himself locked in another contract dispute with Ebbets. The Brooklyn owner became infuriated when Casey returned his contract unsigned, stating that he must have been sent the clubhouse attendant’s contract by mistake. Stengel ended up signing just two weeks before the season. Playing in all but one of the club’s 151 games, he led the Robins in runs scored (69), RBIs (73), doubles (23), triples (12), and home runs (6). Nevertheless, on January 9, 1918, Ebbets, weary of Stengel’s annual holdouts, traded him and second baseman George Cutshaw to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitchers Burleigh Grimes and Al Mamaux and infielder Chuck Ward.

Stengel quickly became disenchanted with Pittsburgh. During his first return to New York, his old teammate Leon Cadore told him about military life. America had entered World War I and many of the players either enlisted or took jobs in essential war-related businesses. Casey decided to enlist and spent the remainder of the war running the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s baseball team. When the war ended, he became embroiled in yet another salary dispute, this time with Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss. Casey unsuccessfully argued that he deserved a raise despite appearing in only 39 games and batting just .246 the previous season. He got off to a good start in 1919, his average hovering near .300 when the Pirates arrived in Brooklyn in May. During a Sunday game Casey was having a rough time—he struck out twice and missed a long fly ball that allowed three runs to score—and the crowd was letting him have it. On his way to the bench at the end of the sixth inning, he saw his old friend Cadore in the bullpen holding a sparrow. Casey placed the bird in his cap, and when he came to bat in the top of the seventh he acknowledged the crowd’s boos by tipping his cap and releasing the sparrow. Even the plate umpire laughed.

Dreyfuss, however, was not amused. On August 9 he traded Stengel to the Philadelphia Phillies for Possum Whitted. Predictably, Casey demanded a salary increase from the Phillies owner. When the raise was refused, he returned home to Kansas City and spent the rest of the year barnstorming. Stengel finally reported to the Phillies in 1920 and put together a solid season, batting .292 with a career-high nine home runs in 129 games. In 1921 he began to be plagued by constant injuries, particularly to his legs; by June 30 he had batted only 59 times. When the trainer handed him some papers, Casey thought he was being sent to the minors. Instead he read that he’d been traded to the New York Giants.

Stengel served mainly as a pinch hitter for the Giants in 1921, but injuries to two outfielders made him the regular center fielder in June 1922 and he batted .368 in 84 games. Nine days before the World Series against the crosstown rival Yankees was to begin, Stengel pulled a leg muscle. He started the first game, going one for four, and then came up lame after his first at bat in Game Two. John McGraw sent in a pinch runner and Casey was done for the year.

The next spring it became apparent that Stengel’s spot on the roster was precarious. Manager McGraw had stockpiled outfielders and when he offered Casey a chance to coach one of the “B” squads, Stengel took it. McGraw took Casey under his wing and began using him as a part-time assistant, letting him coach first base and work with younger players. They would often sit up all night at Mr. McGraw’s home discussing tactics and strategy.

Casey started the 1923 season with a hot streak. His average stood at .379 on May 7 when he was suspended for 10 games for brawling with Phillies pitcher Phil Weinert. For two months Casey saw little action, but in July he got another opportunity to play center field because Jimmy O’Connell was slumping. He hit safely in 20 of the next 22 games and won the starting position. For the third straight year the Giants won the pennant and met the Yankees in the World Series. Stengel’s inside-the-park home run in the ninth inning won Game One for McGraw’s Giants. The moment was immortalized by a Damon Runyon column which began “This is the way old Casey Stengel ran yesterday.” Two days later, Casey hit another home run in Game Three, giving the Giants a 1-0 victory. He created a ruckus by blowing kisses to the Yankee Stadium crowd and thumbing his nose at the Yankee bench as he rounded the bases. Commisioner Kenesaw Landis was at the game and fined Casey for his antics. The Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert was furious and had demanded Casey be suspended, but Landis replied, “Casey Stengel just can’t help being Casey Stengel.” It was his last hurrah as a Giant. One month later he was traded to the Boston Braves.

Stengel batted .280 in 131 games in 1924, but the highlight of the year was his wedding to Edna Lawson while in St. Louis in August. The couple had been introduced at a game at the Polo Grounds the year before. Edna had accompanied Mrs. Emil Meusel, the wife of one of Casey’s teammates. Casey had been pulled from that day’s game for a defensive replacement, so he showered quickly and went to the box-seat section reserved for the players’ wives. The two couples went out to dinner that night, and it would eventually lead to an enjoyable 51 years of marriage. After a quick honeymoon, Casey returned to the team in time for a doubleheader in Chicago. He led the Braves to a sweep with three hits, including a three-run home run in the nightcap, but the club went on to finish last.

Casey and Edna joined a barnstorming troupe that toured England and France that fall. After one game in London, the players were introduced to King George V. They returned to New York and spent a few days with the McGraws before catching a train to California where Edna’s family lived. Her father built them a house in Glendale that would be their home for the rest of their lives.

In 1925 he was hitting only .077 when the Braves sent him to Worcester, Massachusetts, as player-manager and president. Casey played in 100 games and batted .320. He led the team from last place to third while entertaining the fans with his run-ins with the umpires. When an opportunity arose to take over as manager of the Toledo Mud Hens, manager Stengel released himself as a player, and then president Stengel fired himself as manager.

For the next six years Stengel managed the Toledo Mud Hens. He played sporadically after the first year, but he mostly concentrated on managing. In 1927 Toledo won their first pennant ever and the town went crazy. But the team tumbled to sixth place in 1928 and eighth the following year.

Released after the 1931 season, Casey signed on as a coach with his old Pirate teammate Max Carey, who had just been named to replace Wilbert Robinson as Brooklyn manager. Two years later Casey became manager when Carey was fired. He lasted three years, never finishing higher than fifth. Casey’s reputation as a clown grew during his Brooklyn tenure. Not all of this was his fault, as the Dodgers had a reputation for daffiness before he took over the reins. But Casey would joke around while coaching third base to entertain the fans and was always good for a colorful quote to the sportswriters. One highlight for the Dodgers under Stengel was their victories over the Giants in the last two games of the 1934 season, allowing the St Louis Cardinals to win the pennant. This paid back Giants manager Bill Terry, who had asked, “Is Brooklyn still in the league?”

The following year the Dodgers finished fifth, then dropped to seventh in 1936. Despite having one more year on his contract, Casey was let go at the end of the 1936 season. He spent part of the next year traveling and inspecting the Texas oil fields in which he had invested. Casey and Edna made occasional trips to New York, attending vaudeville and theater and enjoying their favorite restaurants.

He returned to baseball in 1938 as manager and part-owner of the Boston’s perennially losing National League club. General Manager Bob Quinn told the press Casey was his third choice, but explained Casey would make the players hustle. He didn’t mention that Casey had invested some of his oil money in the team. Casey enjoyed Boston, but was given little support by management. Casey guided the team to fifth place his first year, but the Braves tumbled to seventh in 1939 and remained there for the next three years. Just before the 1943 season, Casey was struck by a taxi as he tried to cross a street in Boston in the rain. His left leg was severely fractured and he developed a staph infection. He spent six weeks in the hospital. One sportswriter said the cabdriver was the man who did the most for Boston baseball. Stengel never completely recovered from the accident. He always walked with a slight limp afterwards. He returned to manage the last 107 games, winning 47 and losing 60. The Braves were under new ownership. Casey still had the support of GM Quinn, but Lou Perini, the new owner, wanted a change. Under the circumstances Casey thought it best if he resigned, collected his investment money, and returned home to California.

Casey was not out of baseball for long. Early in the 1944 season, the Chicago Cubs hired Charlie Grimm as manager. Grimm was managing the American Association Milwaukee club, and owned the team along with Bill Veeck. Charlie called on his old friend Casey to take over as manager of the Brewers. Veeck was serving with the Marines in the Pacific, so Grimm could not consult him on the hiring. When Veeck received the news, he was furious. He wrote a letter listing his objections, from Stengel’s losing record as a manager to his inability to judge talent. By the time the letter reached Milwaukee, the Brewers had opened up a substantial lead over the rest of the league. Casey led the team to a pennant and saw attendance increase by 200,000. Despite his accomplishments, Casey figured his days would be numbered when Veeck returned from overseas. Casey decided to resign rather than be fired. When Veeck did return home, he realized what a great job Casey had done, and tried to persuade him to come back to the Brewers. Stengel declined, hoping his good work in Milwaukee would lead to another chance in the majors. But there were no openings in 1945.

George Weiss, farm director of the New York Yankees, offered Stengel the managerial position with the Kansas City farm club. Casey reluctantly accepted, knowing that the minor league team was severely depleted by the war. Casey could do little with the Blues, settling for a seventh place finish. Late in 1945, the Yankees were sold to a syndicate headed by Larry MacPhail. Weiss was pushed into the background, and Casey’s status was uncertain. Casey was friends with Cookie de Vicenzo, who had recently sold the Oakland Oaks. He recommended Stengel to the new owner of the Oaks, who was looking for a manager. The job allowed him to spend more time with Edna as they traveled up and down the Pacific coast together.

Casey managed the Oakland team for three years. The Oaks finished second in 1946, losing in the playoff finals to San Francisco. In 1947 they dropped to fourth, but once again made the playoff finals before losing to Los Angeles. The third year was the charm as Casey’s team won the regular season and the playoffs. It was Oakland’s first pennant since 1927. The Oaks were a mixture of veterans like Ernie Lombardi and Cookie Lavagetto and youngsters from the Yankee farm system, including pitchers Frank Shea and Gene Bearden. But Casey’s favorite youngster was a local kid named Billy Martin. Casey worked on Martin’s fielding, hitting him grounders and showing him how to turn double plays.

Back in New York, Stengel’s friend George Weiss had been recommending him for the Yankee job every year since the idea of Joe McCarthy retiring arose. First Ed Barrow, then Larry MacPhail dismissed the idea. Instead MacPhail hired Bucky Harris, who led the Yankees to a pennant in 1947 and narrowly missed another one in 1948. When MacPhail sold his interest in the team to his partners Dan Topping and Del Webb, Weiss became general manager. Weiss promptly fired Harris and convinced the owners to give Casey a chance.

The baseball world was shocked by the announcement that Casey Stengel would manage the New York Yankees in 1949. He was widely regarded as a clown and a failure as a manager. He had never finished in the first division in nine years at the helm of a big-league club. Casey kept a low profile during the off-season and came to spring training ready to evaluate the talent he had inherited. He experimented during spring training, moving players in and out of the lineup almost randomly.

The Yankees opened the 1949 campaign with a come-from-behind victory over Washington. They quickly moved into first place, although Joe DiMaggio was absent because of a heel injury. Casey seemed to have a magic touch, shuffling his outfielders in and out of the lineup based on the opposing pitcher. Harold Rosenthal was the first to use the term “platooning” for Casey’s handling of players. The term was borrowed from football, where it had become more common recently to use different players on offense and defense. Casey actually took the idea from the way his former managers Robinson and McGraw had platooned him during his playing days. While Casey did not invent platooning, Bill James credits him with reviving the strategy after it had been abandoned for years.

DiMaggio returned for a three-game series in Boston in late June. He hit three home runs, drove in nine runs, and led the team to a sweep of the Red Sox. The Sox were 12 games behind the Yankees on the Fourth of July, but Boston caught fire and actually led by a game when the teams met at Yankee Stadium for a showdown in the last two games of the season. The Yankees came back from a 4-0 deficit to win the first game behind the brilliant relief pitching of Joe Page. Then they won the last game of the season, 5-3, to give Stengel his first pennant as a manager. The World Series against Brooklyn did not match the regular-season drama, as the Yankees took it in five games. During the post-series celebration, Stengel said, “I want to thank all these players for giving me the greatest thrill of my life.” He was named Manager of the Year by The Sporting News, an honor he would receive again in 1953 and 1958. Casey’s explanation for his managerial success was, “Keep the five guys who hate you away from the five who are undecided.”

Casey had been deferential to the older Yankee players in his first year, but now his confidence in dealing with the players was restored. He began to emulate his idol John McGraw, ruling the team with an iron hand. Some of the veterans resented this new Stengel. Phil Rizzuto would later say Casey became loud and sarcastic, second-guessing the players, and taking too much credit when things went right.

The Yankees started slowly in 1950 and found themselves trailing the Detroit Tigers in mid-season. Casey dropped the slumping DiMaggio from his usual cleanup spot to fifth. He also put the Yankee Clipper at first base for one game. When Stengel gave DiMaggio a few days off to rest without consulting him, the superstar came back a changed man. Whether because of the rest or his anger at Casey, the 35-year-old DiMaggio began playing like his younger self. He batted over .370 for the rest of the season, while Rizzuto fielded spectacularly and hit .324 to win the MVP award. A rookie lefthander, Whitey Ford, compiled a 9-1 record after being called up in June. The Yankees caught the Tigers in September and won the pennant by three games. They swept the Phillies in the World Series, winning the first three games by one run before clinching the championship with a 5-3 victory.

Casey convinced the Yankee management to institute an instructional school for the young players before spring training in 1951. Among the prospects were Mickey Mantle, Bill Skowron and Gil McDougald. The school became a staple of Yankee spring training. Casey was quickly enamored of the nineteen-year-old Mantle. He moved Mantle from shortstop to the outfield, reasoning that Rizzuto was going to be around for a few more years and Mantle’s quickest route to the major leagues was as an outfielder. The experts were picking the Indians to dethrone the Yankees in 1951. Casey was starting three rookies and had another one in his pitching rotation. Al Lopez said that one of Casey’s greatest assets was his willingness to gamble on young players.

Once again the Yankees started slowly. The White Sox had reeled off 14 consecutive wins and held first place at the all-star break. Mantle had become increasingly frustrated over his strikeouts and was sent down to Kansas City. He was on the verge of quitting until his father straightened him out. Six weeks later he was recalled to the Yanks. Meantime the White Sox faded, and the Indians surged to a three-game lead heading into the last week of August. But the Yankees went 21-10 to close the season and beat out the Indians by five games. Their opponent in the World Series was the New York Giants, fresh from an exciting playoff victory over the Dodgers known as the “Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.” After Bobby Thomson‘s three-run homer in the bottom of the ninth clinched the deciding game for the Giants, it looked like their momentum would carry over to the World Series. The Giants won two of the first three games, but the Yankees roared back to win three in a row and claim their third consecutive championship.

When Joe DiMaggio retired after the season, Casey felt that it was now his team, not DiMaggio’s. Also missing from the 1952 Yankees was second baseman Jerry Coleman. After he was called into military service, he was replaced by Billy Martin. Mantle moved to center field, flanked by Hank Bauer and Gene Woodling. The Yankees received superb starting pitching from Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi and Eddie Lopat. The club seized first place in June and held it until Cleveland caught them in late August. But the Yankees quickly took a two-game lead and never trailed the Tribe the rest of the way. The Yankees defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in a seven-game World Series behind Reynolds’ two wins and a save. Casey had equaled Joe McCarthy’s record of four consecutive World Championships.

The Yankees were clear favorites in 1953. Whitey Ford was back from military service, and young players like Mantle and Martin had another year of experience. The team grabbed first place early and never looked back. In June they ran off an eighteen-game winning streak that gave them a ten-game lead. Stengel was able to maneuver his players masterfully. He would often pinch-hit in early innings when an opportunity arose to break the game open. The Yankees had acquired a good-field, no-hit shortstop, Willie Miranda, who was used after Phil Rizzuto was lifted for a pinch hitter. Casey also juggled his pitching staff. Thirteen different pitchers started a game and ten relievers recorded saves. Once again the Dodgers were their opponents in the World Series. Behind the hitting heroics of Mantle and Martin, the Yankees won their fifth consecutive championship. Casey eclipsed John McGraw’s four consecutive pennants and Joe McCarthy’s four straight World Series victories.

Casey was convinced his club was unbeatable in 1954, declaring in spring training, “If the Yankees don’t win the pennant, the owners should discharge me.” Even with Billy Martin called into the military and Vic Raschi traded in a salary dispute, the Yankees won 103 games, the most of any of Stengel’s teams. Incredibly, they ended up eight games behind the Cleveland Indians who set an American League record with 111 victories. In the middle of the season, Douglass Wallop published a novel called The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant. It later became the hit musical “Damn Yankees.” Stengel was given a copy, but claimed he never read it. The final nail in the coffin came on September 12, when the Indians swept a doubleheader from the Yankees in front of 86,000 Cleveland fans.

The Yankees returned to the top of the American League in 1955. But the Brooklyn Dodgers finally reached “next year,” and took the World Series in seven games behind the stellar pitching of Johnny Podres. The Yankees recaptured the championship from the Dodgers in 1956. The Yankees were a veteran team and had a reputation for partying. Casey would say, “Being with a woman all night never hurt no professional baseball player. It’s staying up all night looking for a woman that does him in.” He also warned the players, “Don’t drink in the hotel bar, because that’s where I do my drinking.”

The team won two more pennants in 1957 and 1958, by margins of eight and ten games, making it four consecutive AL championships. But the Milwaukee Braves beat them in 1957 in a thrilling seven-game World Series. The next year the Braves led New York three games to one. The Yankees came roaring back to win the final three, a feat accomplished only once before.

As Casey’s legend grew, his way of talking became known as “Stengelese.” In 1958 he testified before Congress on baseball’s anti-trust exemption. His forty-five minutes at the microphone were a comic tour de force and added to his reputation for double-talking. When asked to state his background in baseball, he answered, “I had many years that I was not so successful as a ballplayer, as it is a game of skill. And then I was no doubt discharged by baseball in which I had to go back to the minor leagues as a manager.” Finally, after many long and rambling responses, he was asked whether he thought there was a need for anti-trust legislation for baseball. He simply responded, “No.” Mickey Mantle appeared next, and in response to the Senate panel’s initial question regarding the need for the legislation, Mickey replied, “My views are just about the same as Casey’s.”

The Yankees were not the same team in 1959. Near the end of May they were six games under .500. They finished third, fifteen games behind the Chicago White Sox. Mantle led the club with 75 runs batted in and only three pitchers won more than ten games. As a team they scored almost 100 fewer runs and gave up almost 70 more earned runs than the 1958 team. A lot of people felt Stengel was getting too old and was out of touch with his players. Mickey Mantle was one of the players Casey could not reach. He tried to cut down on Mantle’s strikeouts, encouraged him to work on his bunting, and especially, to take better care of his body. Casey complained that Mantle just did what he wanted.

One of the people who thought it was time for Casey to go was co-owner Dan Topping. He had reluctantly gone along with giving Casey a two-year extension after the 1958 season. In 1959 Topping had ordered the closing of Casey’s pet project, the instructional school. He was grooming Ralph Houk as Casey’s replacement, promoting Houk to a coaching job with the major league team. Casey was also criticized by his old Dodger opponent, Jackie Robinson, who accused him of being a racist and sleeping on the bench during games. The Yankees were slow to integrate, fielding their first black player eight years after Jackie broke the color barrier. That player, Elston Howard, said he never felt any prejudice from Casey. Casey did use language that would certainly be considered offensive today, but was quite common vernacular in the fifties. He was effusive in his praise of black players like Satchel Paige, Larry Doby and Howard.

Weiss pulled off a trade with the Kansas City Athletics that proved to be a key to the Yankees return to the top. He obtained Roger Maris for several veterans that were on the decline. Maris would win the Most Valuable Player award in 1960 and 1961. Things started poorly for Casey in 1960 when he was hospitalized shortly after the season began. He suffered chest pains and feared he was having a heart attack. While he recuperated, Ralph Houk filled in for him. He returned after two weeks rest, giving up drinking for the rest of the season. Casey said, “They examined all my organs. Some of them are quite remarkable and others are not so good. A lot of museums are bidding for them.” The Yankees were challenged by the White Sox and Baltimore Orioles all year. New York reeled off a fifteen-game winning streak to end the year and move from a tie with the Orioles to an eight-game victory margin. Casey had tied John McGraw by winning his tenth pennant. Prior to the World Series, Casey replied to the questions about retiring in typical Stengelese, saying “Well, I made up my mind, but I made it up both ways.”

The Yankees faced a young Pittsburgh Pirates team in the World Series. Pittsburgh took Game One, 6-4, but was crushed by the Yankees in the next two games. The plucky Pirates fought back to squeeze by the Yankees in the next two games to take a 3-2 Series lead. The Yankees annihilated Pittsburgh 12-0 in Game Six, setting up one of the most exciting World Series finishing games. Pittsburgh surged to a 4-0 lead in Game Seven, but the Yankees scored seven unanswered runs to take a lead. Things turned in Pittsburgh’s favor in the bottom of the eighth when a double play ball took a bad hop and hit shortstop Tony Kubek in the throat. Kubek left the game, and the Pirates rallied to score five times and take a 9-7 lead into the ninth inning. The Yankees came back in the ninth to tie. Leading off the bottom of the ninth, Bill Mazeroski put the second pitch over the left field wall for an unlikely victory by the Pirates. It was the first walk-off home run to end a World Series. Despite being outscored 55-27, the Pirates were the World Champions.

Five days later, the Yankees called a press conference. Rumors were rampant that Casey would resign. Co-owner Dan Topping talked about Casey’s great work and how he had been the highest paid manger in baseball. He told the press the Yankees were giving Casey a profit sharing payment of $160,000. When Casey came to the microphone, he spoke of the youth movement the Yankees were implementing and stated he had been paid off in full. Pandemonium broke out as reporters rushed to file the story that Casey had been released. When asked if he had been fired, Casey answered “Write anything you want. Quit, fired, whatever you please. I don’t care.” Casey sat down with a drink and talked more with the reporters. He later uttered his famous line, “I’ll never make the mistake of being seventy again.”

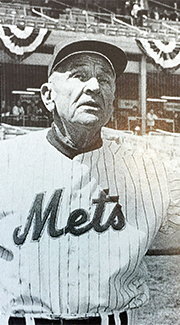

Casey returned home to Glendale to work as the vice-president of the Valley National Bank, which was owned by Edna’s family. In January, 1961, he was attending the opening of a branch office in Toluca Lake, when he slipped and fell, hurting his back. While recuperating, Casey turned down several managing jobs, most notably the Detroit Tigers. At the All-Star Game his old boss George Weiss, who had also been retired by the Yankees, invited him to manage the expansion New York Mets. Casey declined, but Weiss persisted. Finally, on October 2, just before the opening of the 1961 World Series, the Mets held a press conference to introduce Casey as their new manager.

The expansion draft for the two new franchises, the Mets and the Houston Colt .45s, was held the day after the World Series ended. The Mets selected a third-string catcher, Hobie Landrith, with their first pick. Casey explained, “You have to have a catcher or you’ll have a lot of passed balls.” The Mets loaded their roster with several older National League players that New York fans would recognize, including former Dodger favorites Gil Hodges, Don Zimmer, Roger Craig and Clem Labine. While the Mets fared reasonably well during spring training, Casey said he was not fooled. The first regular-season game against St. Louis was a harbinger of things to come. Don Zimmer threw the first ground ball of the year away and Roger Craig balked in a run as the Mets lost to the Cardinals, 11-4. The fans didn’t care, though. They welcomed the team with a parade up Broadway on April 12, 1962, and Casey was given the keys to the city. They lost the first nine games of the year. When the Mets returned home on April 27, their record was 1-11.

The expansion draft for the two new franchises, the Mets and the Houston Colt .45s, was held the day after the World Series ended. The Mets selected a third-string catcher, Hobie Landrith, with their first pick. Casey explained, “You have to have a catcher or you’ll have a lot of passed balls.” The Mets loaded their roster with several older National League players that New York fans would recognize, including former Dodger favorites Gil Hodges, Don Zimmer, Roger Craig and Clem Labine. While the Mets fared reasonably well during spring training, Casey said he was not fooled. The first regular-season game against St. Louis was a harbinger of things to come. Don Zimmer threw the first ground ball of the year away and Roger Craig balked in a run as the Mets lost to the Cardinals, 11-4. The fans didn’t care, though. They welcomed the team with a parade up Broadway on April 12, 1962, and Casey was given the keys to the city. They lost the first nine games of the year. When the Mets returned home on April 27, their record was 1-11.

In May, the Mets won five out of six, including back-to-back extra-inning games, to raise their record to 12-19. Then they lost their next seventeen. The team’s ineptitude inspired Casey’s remark, “Can’t anybody play this here game?” Yet the worse they played, the more the fans adored them. They were considered the fun team, a sharp contrast to the corporate image projected by their American League competitors, the Yankees. The icon of the Mets was Marvelous Marv Throneberry. Marv was less than marvelous when it came to fielding his first-base position. He made seventeen errors in just 97 games. The Mets would go through losing streak of eleven and thirteen games. Their best pitcher, Roger Craig, lost twenty-four times. But the team drew 900,000 fans. Casey charmed the reporters, constantly referring to his team as the “amazin’ Mets.” The Mets set a twentieth-century record for futility with 120 losses, and fittingly hit into a triple play in the last game of the year.

The following season was more of the same. The Mets won eleven more games than they had in 1962 as attendance went up to more than 1 million. But the result was another last-place finish, 48 games behind the pennant-winning Los Angeles Dodgers.

The Mets’ new home, Shea Stadium, was completed during the winter of 1963-64. The Mets lost the first game there to the Pirates when rookie Willie Stargell hit the first home run in the park. Attendance rose due to the new stadium, but the Mets did not. The team finished last once again, improving their win total by only two games. Criticism of Casey’s managerial skills became commonplace. His old adversary, Jackie Robinson, again accused Stengel of sleeping during games. Howard Cosell also criticized Casey during his broadcasts. But Casey was determined to stick it out. He signed a new contract and seemed to be his usual self during spring training in 1965. At an exhibition game at West Point, Casey fell on wet pavement and broke his wrist. With his arm in a sling, he did not miss a game. The Mets continued to lose at the same pace as always. On July 24, 1965, the Mets held their fourth annual old-timer’s game. It was also a celebration of Casey’s forthcoming 75th birthday. The Mets lost their tenth in a row, then the old-timers adjourned to a party at Toots Shor’s restaurant. Casey slipped in the bathroom and broke his hip. Whether the injury was related to drinking was never made clear. But the following day he underwent surgery to implant an artificial hip. Following the advice of his wife, Edna, Casey decided it was finally time to retire. The Mets kept him on the payroll as the vice-president in charge of West Coast scouting.

He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1966, and returned to Cooperstown every year for the induction ceremonies. In 1969 baseball celebrated its centennial by selecting two All-Star teams, the greatest living players and the greatest players ever. Casey received the award as greatest living manager, and attended a ceremony at the White House hosted by President Nixon. That year the Amazin’ Mets astounded the world by beating the favored Baltimore Orioles in the World Series and winning their first World Championship. Casey was presented with a World Series ring by the Mets organization. He wore it proudly the rest of his life.

In August of 1970, the Yankees honored Casey for his accomplishments, retiring his jersey number 37. Casey continued to attend All-Star and World Series games, speak at banquets, and entertain reporters with his stories. Casey summarized his career with the statement, “There comes a time in every man’s life and I’ve had plenty of them.” Edna suffered a stroke in 1973 and moved into a convalescent home. Casey kept the big house in Glendale, assisted by a woman named June Bowlin, who acted as nurse, housekeeper and secretary.

By 1975 he had slowed considerably and was diagnosed with a form of lymphatic cancer. Casey Stengel died on September 29, 1975, in a hospital in Glendale. Edna outlived him by two and a half years. They are buried together in a Glendale cemetery.

Casey Stengel had a long and storied career in baseball, first as a player, then as a manager. He was a solid right fielder for the Brooklyn team and excelled as a platoon player under John McGraw. He accumulated a respectable 159 Win Shares in his career. Bill James ranked him as number 115 among all-time major league right fielders. He became a keen student of baseball under McGraw’s tutelage. He was considered an average manager at best until his tenure as the skipper of the New York Yankees. His record of ten pennants and seven world championships in a twelve year span is unparalleled. Critics will point to the talent of the players he managed and say anyone could have won with the Yankees. Total Baseball only credits Casey with six more wins than expected as Yankee manager, based on the runs scored and allowed by the teams. Even his Yankee players were divided on whether they won because of Stengel’s maneuvers or despite them. In the end, though, Casey will be remembered as a colorful and charismatic character.

Last revised: May 29, 2022

Sources

Maury Allen. You Could Look It Up: The Life of Casey Stengel. Times Books, 1979.

Robert W. Creamer. Stengel: His Life and Times. University of Nebraska Press, 1984.

Joseph Durso. Casey and Mr. McGraw. The Sporting News, 1989.

Lawrence Ritter. The Glory of Their Times. MacMillan, 1966.

Richard Bak. Casey Stengel — A Splendid Baseball Life. Taylor Publishing Co., 1997.

David Halberstam. The Summer of ’49. William Morrow and Co., 1989.

Bill James. The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. The Free Press, 2001.

Bill James. Win Shares. Stats Publishing, 2002.

Casey Stengel file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library

The Sporting News, miscellaneous clippings.

Full Name

Charles Dillon Stengel

Born

July 30, 1890 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

Died

September 29, 1975 at Glendale, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.