Curt Schilling

Curt Schilling’s father, Cliff, served in the United States Army for 22 years, a master sergeant with the 101st Airborne Division who was stationed at Elmendorf Air Force Base adjacent to Anchorage, Alaska, when his son Curtis Montague Schilling was born on November 14, 1966. Curt was the middle child of Cliff and Mary Schilling.

Sgt. Schilling introduced his son to baseball early; a biographical entry on ESPN says, “When Curt was brought home from the hospital, there was a baseball glove in the crib that Cliff had placed there.”1 The same bio continued, “The family moved to Kentucky, Illinois and Missouri before finally settling in Phoenix, Ariz. Curt’s father was a Pirates fan, and the first baseball game Curt ever attended was Roberto Clemente‘s last.”

A power-pitching right-hander, Curt Schilling struck out 3,116 major-league batters, one of only 16 pitchers to join the 3,000 Strikeout Club. Schilling and Roger Clemens are the only two “members” of this exclusive club not yet inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

With a postseason record of 11-2, Schilling holds another distinction: No one with 10 or more postseason decisions has a better winning percentage (.846).2 He has won World Series games for three different franchises – the Phillies, Diamondbacks, and Red Sox. With Randy Johnson, he was co-MVP of the 2001 World Series.3 When pitching for the Red Sox, he won games in each of the three rounds of the playoffs in 2004 and again in 2007, his most courageous performance being his famous “bloody sock” win over the Yankees in the 2004 American League Championship Series, one that he reprised against the Cardinals in that year’s World Series just five days later. He was told by the surgeon who sutured his tendons in place that it was a procedure that probably couldn’t be done a third time.

Ryan Spaeder has pointed out that there were five games Schilling started when his team was facing elimination. In those five games, he pitched to a 1.37 ERA, and his team won all five games. There were three games in which he was given starts when his team had the opportunity to clinch. In those three games, he pitched to a 1.16 ERA, and his team won all three games.4

Schilling struck out 120 and walked 25 in postseason play.

In the regular season, his 3,116 strikeouts are balanced against only 711 walks, 4.38 K’s for every BB. As of 2015 that is the best strikeouts-to-walks ratio of any pitcher to ever play in the majors since 1900 who struck out at least 1,000. Pedro Martinez ranks second with 4.15.

Spaeder pointed out that Schilling threw 64 games in which he struck out at least seven opponents and walked no one. That’s the most of any pitcher in history. Randy Johnson ranks second with 54 and Greg Maddux is third, with 44. He also wrote, “No pitcher in baseball history has both a higher strikeout percentage and a lower walk percentage than Schilling had in his career.”5

Three times – 1997, 1998, and 2002 – Schilling recorded more than 300 strikeouts. Speaking of walks and strikeouts, he set another record in 2002 that dates back to at least 1946 and perhaps to 1900: From May 13 to June 8, he didn’t walk a batter for a stretch that embraced 56 strikeouts. Second and third on the list is Greg Maddux, who had a 53-strikeouts-without-a-walk streak in 2001 and Pedro Martinez, at 49 in 2000.6

Schilling is a six-time All-Star, and finished second in Cy Young voting in 2001, 2002, and 2004. He won 216 major-league games, and lost 146.

By the time Curt was in high school, at Shadow Mountain High School in Phoenix, he was playing baseball, but he didn’t make the varsity until his senior year. There had been talks with scouts, but they were shelved after Schilling suffered a broken left elbow on a hit-by-pitch during the summertime. He enrolled at Yavapai Junior College in Prescott, Arizona, a school that has produced 15 major leaguers through 2014. In 1986 he went to the Junior College World Series, the fifth time a Yavapai team had reached the series. The right-hander was drafted by the Boston Red Sox as their choice in the second round of the January 1986 draft; he signed on May 30.

The Red Sox assigned Schilling to the Elmira Pioneers in the New York-Penn League, where he had a 7-3 record with a 2.59 ERA, 75 strikeouts, and 30 walks in 93 innings. It was a good first start in professional baseball.

In 1987 he maintained a strong strikeouts-to-walks ratio, with 189 K’s and 65 BB’s for the South Atlantic League’s Greensboro Hornets. The team’s record was 55-85, and Schilling’s 8-15 came close to reflecting that. His 3.82 ERA indicates a more difficult season.

Schilling began 1988 at Double A, pitching for Boston’s New Britain Red Sox (8-5, 2.97 in 21 games) but was traded (along with outfielder Brady Anderson) to the Baltimore Orioles for pitcher Mike Boddicker as the Red Sox prepared to make a run for the pennant. He was 5-2 (3.18) for Charlotte, before the Orioles called him to the big leagues in time to make his first appearance on September 7. The Red Sox were visiting Baltimore and Schilling was given the start. The home-plate umpire was Steve Palermo. Curt’s father, Cliff, had died eight months earlier, in January, of brain cancer at age 52.7 Curt later said, “My father was the glue that held us together. When he died, I kind of lost my family.” Curt was said to be “estranged from his mother and older sister.”8

“I saw a scared kid,” Palermo told writer Joe Posnanski years later. He said he saw how nervous Schilling was and told him, “You get that first pitch close, I’ll call it a strike. And we’ll get this game going.” Looking at the play-by-play of the game, it seems Schilling did quite a good job, but the reality on the field was that he had forgotten the signs and was throwing unexpected pitches. He worked seven innings and gave up three runs on six hits, but he walked five. He hadn’t thrown a wild pitch, but the way Posnanski told it, he kept hitting Palermo with pitches. Finally, Palermo said, he went out to the mound with a ball and said, “You’re OK, kid. Just relax. You’re going to make it in this game. You’ve got what it takes. It’s all going to be OK. Just relax and throw strikes.”9 The 4-3 game was won by the Orioles in the bottom of the ninth, but Schilling was gone by then. For the Orioles in September 1988, he lost his next three starts and was 0-3 with a 9.82 ERA.

He was still just 21. It took him a little more time to truly be ready for big-league pitching.

Schilling was a September pitcher again in 1989. After a 13-11 season with Rochester with a good 3.21 earned-run average, he got the call back to Baltimore and was 0-1 with a 6.23 ERA in five appearances. He began the 1990 season with Rochester again, but was brought up near the end of July and got his first extended taste of major-league pitching, working exclusively in relief, working 46 innings in 35 games, with an excellent 2.54 ERA. He did book his first win, but was tagged with two more losses. On January 10, 1991, he was traded to the Houston Astros (with Steve Finley and Pete Harnisch) for Glenn Davis.

Now in the National League, Schilling worked 56 games in relief in 1991, with a 3-5 record and a 3.82 ERA. Just before the 1992 season began, he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies straight up for Jason Grimsley on April 2.

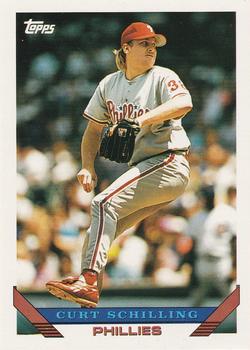

With the Phillies, Schilling settled in. His first year was also manager Jim Fregosi‘s first. Schilling pitched nine seasons with the Phillies and won 101 games. His first year, 1992, was one of the best – a 2.35 earned-run average and a league-leading WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) of 0.990. With 26 starts (and 16 relief appearances), Schilling won 14 games, losing 11 for a sixth-place team. He threw 10 complete games.

It was also the year Schilling married Shonda Michelle Brewer, a graduate of Towson State University in Maryland whom he met when she was moonlighting at Foot Locker. She came from a blue-collar family in Baltimore.10

The 1993 Phillies went all the way to the World Series. Schilling (16-7) and Tommy Greene (16-4) tied for the team lead in wins. Schilling was named MVP of the NLCS against Atlanta. In the World Series, against the Toronto Blue Jays, he was tagged for seven runs (six earned) in Game One, and bore the loss. In Game Five, when a Jays win would have given them the championship, Schilling threw a five-hit, 2-0 shutout. Toronto won Game Six and the Series.

The 1993 Phillies went all the way to the World Series. Schilling (16-7) and Tommy Greene (16-4) tied for the team lead in wins. Schilling was named MVP of the NLCS against Atlanta. In the World Series, against the Toronto Blue Jays, he was tagged for seven runs (six earned) in Game One, and bore the loss. In Game Five, when a Jays win would have given them the championship, Schilling threw a five-hit, 2-0 shutout. Toronto won Game Six and the Series.

The Phillies didn’t have another season that even got them to .500 until 2001, at which point Schilling was gone.

Schilling had two really rough years in 1994 and 1995. Starting the 1994 season with a subpar spring training and then going 0-7 made it clear that something was wrong. Though among the losses were a 2-1 one-hit effort through seven and a 1-0 loss, his earned-run average climbed to 5.40 during the stretch through May 16, after which he didn’t pitch for two months because of surgery to remove bone spurs on his right elbow. Then the player strike brought about an end to the season; Schilling looked back on a 2-8 year. In 1995 he suffered a torn labrum and after July 18 needed season-ending surgery. He came back on May 14, 1996, with seven innings of no-run ball and was clearly back on track. In 1996 Schilling started 26 games and led the league with eight complete games. His won-lost record reflected the team; he was 9-10, but he pitched with a 3.19 ERA, ranking him seventh.

Schilling’s first All-Star Game was in 1997; he pitched two innings, striking out three and not allowing a run. By year’s end, he had 319 strikeouts, leading the league, and he had a record of 17-11 (2.97). He was named to the All-Star team in both ’98 and ’99. He didn’t appear in 1998, but started the 1999 game (at Fenway Park) and bore the loss, giving up two runs in two innings. He struck out an even 300 opponents in 1998 and led the majors with 15 complete games. In both 1998 and 1999, Schilling won 15 games. From July 23, 1999, when he had to leave a game due to right biceps and shoulder issues, to September 3, he appeared in only one game, giving up eight runs.

In 2000 there was a change of scene. Schilling had a middling 6-6 (3.91) record as the trade deadline approached; on July 23, the Arizona Diamondbacks traded four players so they could add Schilling to their rotation: The Phillies got Omar Daal, Nelson Figueroa, Travis Lee, and Vicente Padilla. Schilling more or less continued as he had been, 5-6 with a 3.69 ERA the remainder of the season.

But in 2001 the Diamondbacks got everything they had been hoping for, and maybe more. Schilling had a dominant 22-6 season, with a 2.93 earned-run average, leading the league in wins and coming in second only to teammate Randy Johnson in ERA.

Come the postseason, Schilling shone. He threw a three-hit shutout in Game One of the Division Series against the Cardinals. He won the clinching Game Five with a 2-1 complete game. In the League Championship Series, he pitched once, again throwing a complete game and again giving up just one run. This put Schilling in position to start Game One of the World Series against the New York Yankees. He allowed three hits and one run in seven innings, winning the game and improving his record to 4-0 in the 2001 postseason. At this point he had a 0.79 ERA. He started two more games in the World Series, Game Four (again seven innings, three hits, one run) and Game Seven (7⅓ innings, with six hits and two runs.) Both Games Four and Seven were closely contested games, the Yankees winning Game Four in the 10th inning and the Diamondbacks winning the deciding Game Seven with two runs in a come-from-behind bottom of the ninth.

Schilling’s final record in the 2001 postseason was 4-0 (1.12) and he was named co-MVP of the World Series with Randy Johnson. Johnson had been 21-6 in the regular season, and was 5-1 (1.52) in the postseason, 3-0 in the World Series itself, winning the final Game Seven when he threw the final inning and a third in hitless relief.

The next season, 2002, was very similar to 2001. Schilling won one more game and lost one more, for a still very enviable 23-7. His ERA nudged up to 3.23, a figure most pitchers could only aspire to get down to. His 0.968 WHIP led the league and was the best of his career. For the second year in a row, Schilling placed second in Cy Young voting. (Both times Randy Johnson was first.) Schilling started the All-Star Game again, giving up one hit and no runs in the first two innings. When it came to the postseason, he couldn’t have pitched much better – one run in seven innings of Game Two of the Division Series against St. Louis, but the Cardinals swept.

Schilling’s 2003 season saw him have an appendectomy and then, on May 30, he was struck twice on his right hand by batted balls and broke the hand. He battled through the season and emerged with a 2.95 ERA but a record of 8-9. (No pitcher on Arizona had more than 10 wins.)

After the 2003 season, with an excruciating last-minute loss to the Yankees in the ALCS, the Boston Red Sox were ready to make some dramatic moves. The team was in the first couple of years of new ownership and with a new GM on board in Theo Epstein. They wanted to get Curt Schilling and they wanted to get a new closer. Epstein made a later-celebrated trip to the Schilling household in Scottsdale, and he came prepared with just the sort of data that would show he’d done his homework and impressed the detail-oriented Schilling. Gracious hosts, the Schillings even invited Epstein and assistant GM, Jed Hoyer, to have Thanksgiving dinner at their home. Some of the data showed that Fenway Park was by no means necessarily a bad park for a right-handed power pitcher.

Schilling broke the mold in a number of ways, and one of them was in acting as his own agent. He talked turkey with the Sox emissaries and said he’d be on board if they could pull off a deal with the Diamondbacks. In a November 28, 2003, deal, the D’backs got four players for Schilling – Casey Fossum, Brandon Lyon, Jorge de la Rosa, and minor-leaguer Mike Goss. In January, Boston got its closer in Keith Foulke.

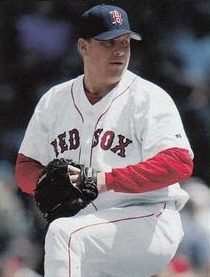

Curt Schilling was back with the team that first drafted him. On signing, he famously said, “I guess I hate the Yankees now.” Not that he hadn’t already helped defeat them in the 2001 World Series. He also filmed a Ford commercial that ran in New England saying he was coming to Boston to win a championship. That’s exactly what he helped do, with some unwanted but very real drama come playoff time.11 He was also reunited with Terry Francona as his manager, Francona having managed the Phillies from 1997 through 2000 and having been hired by the Red Sox not that long after Schilling had signed.

Schilling was legendary for his preparation, and maintained a number of notebooks which he was sometimes seen to consult on the bench between innings. He was a good fit for catcher Jason Varitek, who kept equally well informed. Schilling praised his catcher on many occasions; one comment summarized it all: “He’s one of the few catchers I have ever played with who I feel places 10 times more emphasis on his job behind the plate than he does at the plate.”12

Schilling led the American League with 21 wins; he lost six times, and worked to a 3.26 ERA. Johan Santana won the Cy Young; Schilling again finished second. The Red Sox and Yankees met again in the ALCS. Schilling won Game One in the Division Series against the Angels, but at a cost that appeared evident when it happened; he seemed to come up lame after making a play by the first-base line in the seventh inning. “I felt the tendon tear,” he said later.13 The Red Sox swept, so Schilling wasn’t called on again until the ALCS. There he also pitched the first game, but right from the start it was clear he was hampered. Schilling gave up six runs in three innings and it looked probable that his season was done, and the Red Sox hopes would be dashed yet again.

The Yankees took the first three games, the third one a 19-8 beatdown in Boston. No team in history had ever come back from a three-games-to-none deficit and won a playoff series. But this year’s Red Sox team was resilient. Dave Roberts stole a base; the Red Sox tied Game Four in the bottom of the ninth. In the bottom of the 12th, David Ortiz won it on a walkoff homer. In Game Five, Ortiz won another one in extras, a walkoff single in the bottom of the 14th. The two teams traveled to Yankee Stadium to pay Game Six, and Curt Schilling had a medical procedure done by Dr. Bill Morgan on his damaged ankle to temporarily stitch his tendons back into place.14

There was some seepage of blood from the procedure and it shows through Schilling’s white sanitary stockings while he was on the mound; the 4-2 win was built on Schilling’s seven innings of one-run, four-hit pitching and a surprise three-run homer hit by Red Sox second baseman Mark Bellhorn. The Red Sox won Game Seven, a game that wasn’t even close, over a now-demoralized New York team.

The Red Sox had won four in a row, and went on to make that eight consecutive wins, sweeping St. Louis in the World Series. Schilling pitched Game Two, at Fenway Park, allowing just an unearned run on four hits in six innings, again pitching on a sutured ankle, one that Dr, Morgan said could not have been rigged up for a third time. He got the win.

The Game Two victory made Curt Schilling the only pitcher to win a World Series game for three different teams. He’d won for the Phillies, Diamondbacks, and now the Red Sox.

After offseason surgery, Schilling was back in 2005 but his three starts in April were all poor ones and other injuries kept him from pitching again until July 14. “I came back way too early,” he told ESPN’s Bill Simmons after the season.15 He worked exclusively in relief, primarily as the closer, until August 25, when he resumed starting. His record was 8-8 (with nine saves) and a 5.69 ERA. The Red Sox won the wild card again, but were swept by the White Sox in the Division Series and Schilling was not used.

In 2006 Schilling improved to a sub-4.00 ERA (3.97), with a record of 15-7 in 31 starts. He reached 3,000 strikeouts on August 30 in Oakland.

Schilling’s final year on the mound was 2007, and he went out with glory, winning one game each in the Division Series (Game Three in Anaheim, seven innings, no runs), Game Six in the League Championship Series against Cleveland (seven innings, two runs), and Game Two in the World Series against the Colorado Rockies (5⅓ innings, one run). There had also been an unsuccessful start but a no-decision in ALCS Game Two.

On June 7 Schilling threw 8⅔ innings of no-hit ball against Oakland, only to yield a single. He was 9-8 for the season (3.87). He signed to come back for one last year in 2008, but was physically unable to perform, so – though anti-climactically – his last work from a major-league mound was his win in Game Two of the 2007 World Series.

Never one to shy from interaction with the public or the media, Schilling had been active on the Internet and with his own blog from at least the start of his time in Boston, and he was an inveterate gamer who had launched his own company in 2006, called 38 Studios, and who was determined to develop and launch a role-playing video game, Kingdoms of Amalur: Reckoning, which was indeed launched in February 2012. 38 Studios had relocated to Rhode Island, thanks to the state’s Economic Development Corporation, which had wooed the company away from Massachusetts with a $75 million loan. The game was well received at first and reportedly sold well over 300,000 copies in its first month. But it had been very expensive to develop, and sales were not sufficient to cover costs as well as ongoing development of a new massively multiplayer game under the working title Project Copernicus. The studio was unable to meet a scheduled repayment, and unable to meet payroll. It ultimately went bankrupt, amid mutual recriminations including the studio’s charge that the state had failed to come through on promises to fund the completion of the second game, which might have proved sufficiently successful.

For its part, the State of Rhode Island has sued Schilling and officials of its own Economic Development Corporation, alleging fraud and other acts that misled the state into granting 38 Studios the $75 million loan, which Rhode Island’s taxpayers are obliged to repay.16 (The loan and its consequences became the subject of a long-running battle in the state’s political circles. Some have suggested that it soured the state on providing financial assistance that might have help keep the Pawtucket Red Sox in Rhode Island rather than moving to Worcester, Massachusetts.)

A writer for Forbes once said, “Schilling overdoses on confidence.”17 Perhaps believing too strongly in his vision, in the product, and in himself, Schilling had pledged personal guarantees, and that came back to bite him as the company was forced into bankruptcy. This cost Schilling much of what he had been able to save from his earnings as a pitcher.

Working on the game took a toll, one that Schilling never mentioned during all the controversy over the financial problems and collapse of 38 Studios. In November 2011, he suffered a serious heart attack. The story only emerged two years later.18

The Schilling family name has long been associated with charitable causes. They became active in the fight against ALS (Lou Gehrig‘s disease) when Pennsylvania computer consultant Dick Bergeron was stricken with the disease in 1992. Beginning in 1993, Curt and his wife, Shonda, launched Curt’s Pitch for ALS, which raised money for every strikeout he threw, the money to be used to help provide better quality of life for victims of the disease.19 Within the first 15 years, they had raised over $10 million. The Schillings’ oldest child, of four, is named Gehrig. Gabriella, Grant, and Garrison are the couple’s three other children.

After Shonda Schilling was diagnosed with malignant melanoma in 2000. She had to undergo five surgeries to rid herself of the cancer. Part of the Schillings’ response involved the founding of the Shade Foundation in 2002, described as “the only national children’s foundation devoted to skin cancer education and prevention.”20

Then in February 2014, Curt himself was diagnosed with cancer. The information was kept private for months but he had mouth cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, “which he believes was caused by a 30-year smokeless tobacco habit. He underwent radiation and chemotherapy, lost 70 pounds, had two bouts with pneumonia and a painful staph infection.”21 Stan Grossfeld wrote a lengthy feature on his addiction.22 On June 25, 2014, Schilling announced on Twitter that his cancer was in remission and wrote, “Start the 5 year clock!”

The Sports Illustrated article briefly noted other challenges the Schilling family has faced: “Gehrig battled an eating disorder during his pre-teen years. Gabby has had some issues with her hearing. Grant has Asperger Syndrome, a form of autism.”

That same article noted how Schilling had defended his daughter against cyber-bullies, quoting Gabby herself, “I didn’t really like all the attention it got. But I began to see what he was doing wasn’t just for me, but it was putting a spotlight on Internet bullying. I think he ended up getting a really good message out there.”23

Shonda Schilling had sent messages of her own over the years, including becoming a marathoner after her cancer diagnosis, her 2005 run in the Boston Marathon alone raising over $50,000 for the Shade Foundation.24 In March 2010, William Morrow published her book, The Best Kind of Different: Our Family’s Journey with Asperger’s Syndrome.25

Asked in 2006 what he saw himself doing 10 years in the future, he replied, “Being a dad. I can’t wait to pay back my wife and kids for the time they have sacrificed for my career. I owe them that.”26

Schilling has received a number of recognitions for his charitable efforts, such as the 2001 Hutch Award (named after Fred Hutchinson) and the Roberto Clemente Award. In December 2002 Worth magazine named him its “Young Benefactor of the Year.”27 He later received the 2004 “Good Guy” award from The Sporting News. In 1996, USA Today’s Weekend magazine had named him “Baseball’s Most Caring Athlete.”

In 2010 Curt Schilling was honored with inclusion in the Arizona Sports Hall of Fame, and in 2012 he was inducted into the Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame.

Any candidate for the National Baseball Hall of Fame needs 75 percent of the votes from the members of the Baseball Writers Association of America who participate in the election. Schilling received 39.2 percent in the totals announced in January 2015, a significant 10 percent increase from the previous year (down itself from the 38.8 percent he had received in 2013.) Asked for comment afterward, he made some good points about John Smoltz (who had quite similar stats) getting elected (with 82.9 percent of the votes) primarily because of Smoltz’s association with the Atlanta Braves team that had won 14 consecutive trips to the postseason (ignoring 1994, when there was no postseason play). Smoltz has a 213-155 record (3.33 ERA) in the regular season and an exceptional 15-4 (2.67) record in the postseason. As noted above, Schilling’s record in the regular season was 216-146 (3.46) with an 11-2 (2.23) record in the postseason.

Schilling suggested that his outspoken support of Republicans running for political office may have cost him 100 or more votes in his first years of eligibility. He later said he’d been joking. But Schilling has always been outspoken (Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy dubbed him a “blowhard” and wrote that he was incapable of saying, “No comment.”) Tom Verducci wrote, “Schilling has always been a man without a mute button.”28 That has often rubbed people the wrong way. The subjective opinions of sportswriters have often been evident in MVP, Cy Young, and Hall of Fame voting. Schilling himself has said that he doesn’t like doing interviews but always viewed it as a responsibility that comes with the job.29

Suffolk University marketing professor Daniel Ladik looked at it this way: “Schilling is a proven winner, a workhorse who wears his passion on his sleeve.”30 Red Sox GM Theo Epstein had his thoughts about Schilling’s self-motivation. “One of the things people didn’t realize about Schilling is that he was really motivated by fear, fear of failure,” Epstein said. “He really did not want to fail, and he was very cognizant of his fear of failure. So he worked himself up through his nerves to go out and dominate to the best of his ability every time he had the ball. That was where some of the ‘clutchness’ came from, the realization that he had about how much he hated failure, and how much he feared failure.”31

In 2010 ESPN hired Schilling as a studio analyst for Baseball Tonight, and in December 2013 he was given a multiyear contract extension, which included his joining the network’s Sunday Night Baseball broadcast team.32 Even that achievement had its potholes. In August of 2015, Schilling was yanked from ESPN telecasts of the Little League World Series after a tweet on Twitter in which he compared Muslim extremists to Nazis in Germany. A contrite Schilling said: “Bad choices have bad consequences and this was a bad decision in every way on my part.” But after other inflammatory tweets, ESPN in September removed Schilling from its Sunday Night Baseball telecasts for the remainder of the season.33

Over the years, he seemed to become more vocal politically, and controversially so, perhaps intentionally. In 2021, he fell short of the number of votes necessary to be elected to the Hall of Fame, receiving 71 percent of the writers’ vote (285 of 401), prompting headlines such as Politico’s “Baseball Hall of Fame rejects politically outspoken star Curt Schilling.”34 Boston Globe columnist Dan Shaughnessy, no stranger to needling himself, wrote a column calling out Schilling for his support of the January 6, 2021 insurrection, among other things.35 Schilling asked to be removed him from consideration on the ballot for 2022. He was not, and his percentage dropped to 58.6%.

Last revised: July 6, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Schilling’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rob Neyer and Tom Ruane for assistance.

Notes

1 espn.go.com/mlb/player/bio/_/id/2112/curt-schilling.

2 Mariano Rivera had a record of 8-1, and a much better 0.70 ERA, but lacked the one decision that would vault him to the (admittedly arbitrary) 10-decision level. One should note Lefty Gomez at 6-0 and Orlando Hernandez at 9-3. John Smoltz, a 2015 Hall of Fame inductee, stands at 15-4.

3 A good feature on the Johnson/Schilling duo at the time is Tom Verducci’s “The Power of Two,” Sports Illustrated, December 17, 2001. Interestingly, Schilling won a World Series game for the Phillies while he was in his 20s, for the Diamondbacks while he was in his 30s, and for the Red Sox while he was in his 40s.

4 Ryan Spaeder, “Curt Schilling Should Be in the Hall of Fame, and It’s Not Close,” The Sporting News, January 21, 2015.

5 Ibid.

6 Data courtesy of Tom Ruane of Retrosheet, email to author July 26, 2015.

7 The ESPN profile (see note 1) reported that Schilling arranged to leave a ticket for his departed father at each game he pitched.

8 Bob Carter, “Pitching Ace Deals Best Under Pressure,” ESPN.com, undated. Retrieved on October 8, 2015, from espn.go.com/classic/biography/s/Curt%20Schilling.html.

9 Joe Posnanski, “Schilling paying back Palermo’s kindness,” KansasCity.com, February 8, 2003.

10 Bella English, “Heading for Home; Baseball Brings Glory to the Schillings, But Their Philanthropy Makes Them Value Players in the Community,” Boston Globe, February 17, 2004: F1.

11 Gordon Edes wrote a lengthy feature which shows Schilling’s mindset at the time. See “New Sox Seem to Fit; Why Schilling See Boston as the Right Move,” Boston Globe, December 3, 2003.

12 Lisa Olson, “Spilling Guts & Blood,” USA Today, July 17, 2005: 52.

13 Author interview with Curt Schilling, April 18, 2013.

14 The full story of the procedure is told through interviews with Dr. Morgan and Curt Schilling and appears with a photograph of Schilling’s ankle in Allan Wood and Bill Nowlin, Don’t Let Us Win Tonight: An Oral History of the 2004 Boston Red Sox’s Impossible Playoff Run (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2014).

15 Bill Simmons, “Curious Guy: Curt Schilling,” Page 2, ESPN.com, January 25, 2006.

16 Associated Press, “Curt Schilling Sued Over Loan,” October 1, 2012.

17 David Armstrong, “Shilling Schilling,” Forbes, September 3, 2007.

18 Stan Grossfeld, “New Lease on Life,” Boston Globe, August 11, 2103: C1.

19 The work continues today through The ALS Association. See alsa.org/.

20 shadefoundation.org.

21 Jeff Bradley, “In Defending Daughter, Curt Schilling Becomes Powerful Antibullying Voice,” si.com/mlb/2015/06/19/curt-schilling-daughter-twitter-gabby. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

22 Stan Grossfeld, “Schilling Fights His Toughest Battle – Trying To Quit a Long-Standing Addiction,” Boston Globe, July 6, 2004: C1.

23 Jeff Bradley, SI.com, op. cit.

24 Joan Freedman, “Role Reversal,” SI.com, April 17, 2005.

25 For a nice story on the genesis of the book, see Stan Hochman, “Shonda Schilling, On Handling Life’s Curveballs,” New York Daily News, April 6, 2010.

26 Lisa Olson, “Spilling Guts & Blood,” USA Today, July 17, 2005: 53.

27 Worth, December 2002: 68.

28 Tom Verducci, “The Power of Two,” Sports Illustrated, December 17, 2001.

29 Lisa Olson, “Spilling Guts & Blood.”

30 Naomi Aoki, “On, Off the Mound, Schilling Makes His Pitch,” Boston Globe, June 13, 2004: A1.

31 Adam Kilgore, “Schilling Puts It in Writing,” Boston Globe, March 24, 2009: C1.

32 Chad Finn, “ESPN Adds Curt Schilling to Sunday Night TV Booth,” Boston Globe, December 9, 2013.

33 Bob Raissman, “ESPN Suspends Curt Schilling for Rest of MLB Regular Season, Wild Card Game,” New York Daily News, September 3, 2015.

34 David Cohen, “Baseball Hall of Fame rejects politically outspoken star Curt Schilling,” Politico, January 26, 2021. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/01/26/curt-schilling-baseball-hall-fame-462801.

35 Dan Shaughnessy, “Curt Schilling falls short of Baseball Hall of Fame induction, and that’s a good thing,” Boston Globe, January 26, 2021. https://www.bostonglobe.com/2021/01/27/sports/curt-schilling-falls-short-baseball-hall-fame-induction-thats-good-thing/

Full Name

Curtis Montague Schilling

Born

November 14, 1966 at Anchorage, AK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.