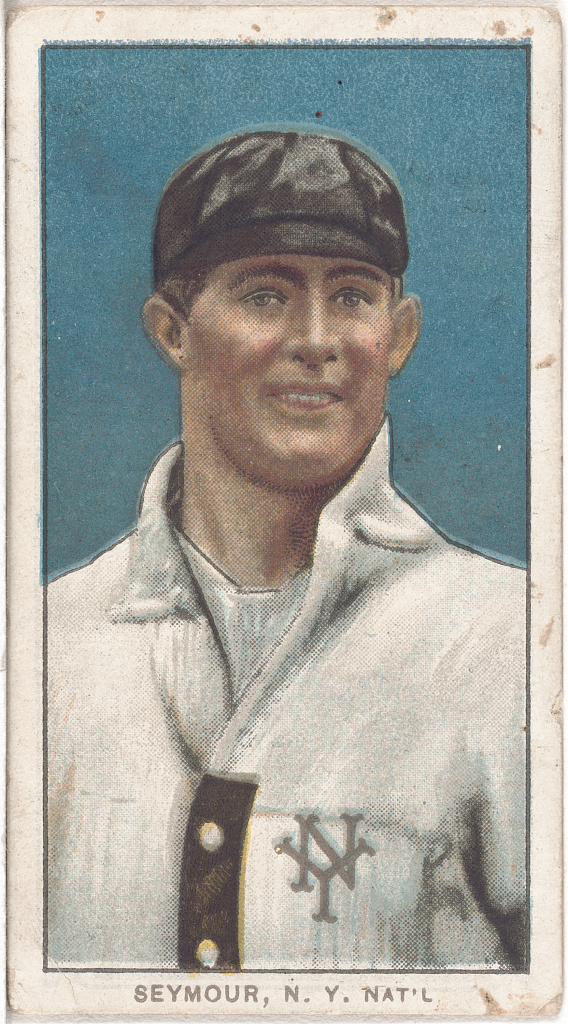

Cy Seymour

If a young, successful major league pitcher had decided to become an outfielder in 2001, it would have been news. And if he had hit above .300 for the next five straight years, culminating in 2005 by winning the league’s batting crown with a .377 average, he would have graced magazine covers. Finally, if upon his retirement in 2010, he had accumulated 1700 hits and generated a lifetime batting average of .303 to go along with his sixty-plus pitching victories, writers would be salivating at the opportunity to elect him to the Hall of Fame.

If a young, successful major league pitcher had decided to become an outfielder in 2001, it would have been news. And if he had hit above .300 for the next five straight years, culminating in 2005 by winning the league’s batting crown with a .377 average, he would have graced magazine covers. Finally, if upon his retirement in 2010, he had accumulated 1700 hits and generated a lifetime batting average of .303 to go along with his sixty-plus pitching victories, writers would be salivating at the opportunity to elect him to the Hall of Fame.

A century ago there was just a player who collected 1723 hits and became a lifetime .303 hitter after winning 61 games as a major league pitcher. His name was James Bentley “Cy” Seymour, perhaps the greatest forgotten name of baseball. In 1898 Seymour won 25 games and led the league in strikeouts; seven seasons later, in 1905, he won the National League batting crown with a .377 average. Since 1893 only one player in the history of the game, Babe Ruth, combined to ever have more pitching victories and more hits than Seymour. The second most versatile player who ever played the game is almost totally unknown.

Of the approximately fourteen thousand players [1] who have made it to the major leagues since 1893 only a few have competed both on the pitcher’s mound and in the batter’s box. A few well-known players (Sam Rice, Stan Musial, George Sisler) began their careers as pitchers but became better known as hitters. Others, like Mike Marshall and Bob Lemon switched from the field to the mound.

Only a handful, however, enjoyed success as both hitters and pitchers. Smokey Joe Wood‘s blazing fastball enabled him to win 116 games before he blew out his arm, forcing him to switch to the outfield. He retired with 553 hits and a respectable .283 batting average. Rube Bressler began his career as a pitcher in 1914, compiling a 26-32 record with Philadelphia and the Reds; he then became a full-time outfielder, principally for Cincinnati and Brooklyn. Between 1921 and 1932 he collected 1170 hits and produced a lifetime .301 batting average. Hal Jeffcoat, on the other hand, began the first six years of his career as an outfielder with the Cubs and finished the last six as a pitcher with the Cubs and the Reds. He appeared in 245 games as a pitcher and compiled a 39-37 record as well as accumulating 487 hits and a lifetime batting average of .248.

Since 1893, when the pitching rubber was moved back to sixty feet, six inches, only two players in major league baseball have pitched more than 100 games and collected 1500 hits. [2] Babe Ruth (1914-35) stroked 2873 hits in his career and pitched in 163 games (94-46, 2.28 ERA). The other player was Cy Seymour (1896-1913), who accumulated 1723 hits and pitched in 140 games (61-53, 3.76 ERA). Seymour’s pitching career highlights include a 25-victory season with a league-leading 239 strikeouts in 1898, the best of all pitchers during the transition era of 1893 to 1900. In 1905 his .377 batting average led the National League in hitting. In addition to his hitting crown that year, he led the league in hits (219), doubles (40), triples (21), RBI (121) and slugging average (.559). With the exception of doubles he led both the National and American Leagues in all of these categories and was second in home runs (8), one behind the leader. [3] He also led the league and the majors in total bases (325), production (988), adjusted production (175), batter runs (64.7), and runs created (153). His highlight seasons of 1898 and 1905 should not overshadow the fact that he was able to leave two rather distinct and remarkable baseball career performances that deserve more scrutiny.

As Harold Seymour (no relation) reminds us, there is a constant struggle in baseball between the offense and defense. [4] Swinging back and forth between pitching and hitting, the game constantly re-figures itself. The era prior to 1900 saw an explosion of hitting after the pitching distance was moved back to 60 feet, six inches. A pitcher at the close of the 19th century had to cope with a changed pitcher’s mound and deal with batters who, it may have seemed, could foul off pitch after pitch until the curfew was declared. [5] The situation soon changed – to the detriment of the hitter. The first two decades of the twentieth century are generally regarded as the Deadball Era. The foul strike rule, i.e. the first two fouls became strikes in 1901 (NL) and 1903 (AL), the spitball and all its variations, and the fact that only one or two balls were used per contest contributed to a game that was considerably different from the one seen today. But Cy Seymour was a pitcher in a hitting era and a hitter in a pitching era. He managed to combine the abilities of hitting and pitching into an exceptional and rare career, yet perhaps because of this obverse situation he is mysteriously forgotten. [6]

The 24-year-old Seymour began his professional career, in 1896 as a pitcher for Springfield of the Eastern League. Prior to that he had been playing semi-pro ball in Plattsburg, New York, for a reported $1000 a month. [7] His good fortune in Plattsburg, if true, undoubtedly may have delayed his arrival to Organized Baseball. His 8-1 record earned him a call-up to the New York Giants later that year where he won two games and lost four in eleven appearances. In 1897, despite being initially being labeled a “balloonist” and “aerialist” for his penchant to suddenly get wild and excitable [8] and which the New York Times citing him as “the youngster with a $10,000 arm and a $00.00 head,” [9] the left-hander began to blossom [10] as a major league pitcher. The New York Herald was able to say at the end of the season that “Cy is rapidly improving, occasionally he gets a slight nervous chill, but by talking to himself with words of cheer and taking good self advise he lets the wobble pass away.” [11] His eccentric self-counsel may have gained ridicule from some fans but he was able to compile a 18-14 record [12] with a 3.37 ERA for the third-place Giants (83-48, 9.5 games behind Boston); he led the league in strikeouts per game (4.83); fewest hits allowed per game (8.23); and struck out 149 batters, second only to Washington’s James “Doc” McJames with 156. Seymour allowed batters to hit only .242 against him, the best in the league, helping to offset his league-leading 164 walks.

His 1897 record indicates that he was becoming a peer of future Hall of Famers Amos Rusie and Charles “Kid” Nichols of Boston. Of the 21 pitching categories listing the top five performers in Total Baseball, Seymour ranks first in four categories and second in another; Rusie ranked first in one category (ERA 2.54), second in 9, third in one and fourth in one, while Nichols clearly led the league, being first in ten different categories and placing within the top five in all but three. [13]

In 1898 Seymour improved his record to 25-19 [14], dropping his ERA to 3.18 for the disgruntled seventh-place Giants. He led the league in strikeouts with a total of 239, sixty-one ahead of his nearest rival, Doc McJames. He again led the league in strikeouts per game (6.03). In addition, to appearing in 45 games as a pitcher, he began to take the field near the midpoint of the season, primarily as an outfielder. As with Babe Ruth 22 years later, [15] his playing in the outfield had little to do with managerial insight and more with a combination of injuries and the light hitting of the Giant outfielders. He was to bat .276 in 297 plate appearances, giving rise to speculation that he might be converted to a full-time outfielder despite the admonition by William F. H. Koelsch in Sporting Life: “The suggestion that Seymour be placed in the outfield permanently is more than a rank proposition. As long as Seymour has the speed he has now he is more valuable on the slab than anywhere else.” [16] Indeed the Giants’ management was faced with a dilemma; his forty-five pitching appearances and his 356⅓ innings were second only to league leader “Brewery Jack” Taylor of St. Louis. Yet the Giants were an anemic hitting squad that was clearly being carried by the superior pitching of Rusie (who was also a good hitter) and Seymour. Seymour’s pitching featured a fastball, a sharp-breaking curve, a screwball and a wildness (he led the league in walks from 1897 through 1899) that must have induced a certain a terror into the 530 batters that he struck out over the same period. Veteran catcher “Uncle Robby” Wilbert Robinson said he had never seen anyone pitch like Cy, first throwing high around the batter’s head and then dropping the next pitch around his feet, causing the batter “to not know whether their head or feet were in most danger.” [17] The second most prolific strikeout artist in those years was Kid Nichols, who trailed Seymour by 57 strikeouts. [18]

The 1898 season represents the apex of Seymour’s pitching career; his 25 wins were nearly one-third of the New York team’s total. He threw four shutouts (Nichols had five), two one-hitters, one three-hitter, four four-hitters and six five-hitters. [19] Another 25-game winner in 1898, Cy Young, threw one shutout, two three-hitters and one five-hitter. [20] Some were even suggesting that Seymour had supplanted Rusie as the ace of the Giants’ pitching staff. The New York press said he had the best curve in the league and that “he could win with only five men behind him” and that he had as much speed as Rusie ever had. [21] He led the team in innings pitched, starts (43), and wins. [22] With such accomplishments he could naturally expect a handsome new contract for 1899, but Andrew Freedman was to stand in his way.

Freedman, a New York City subway financier and Tammany Hall politician, purchased the controlling interest in the Giants in 1895 for $54,000. He quickly antagonized just about everyone in baseball when he attempted to run the team as if it were part of Tammany Hall. He banned sportswriters who were critical of the Giants from the Polo Grounds. When those same reporters purchased a ticket, Freedman had them removed from the park. [23] Freedman, unlike most National League magnates, regarded his team as a plaything and firmly believed that uppity players must always be put in their place.

In 1897 Amos Rusie had the temerity to hold out for the entire season rather than accept a $200 deduction in his 1896 salary for allegedly not giving his best in the concluding games of the season. Throughout 1897 the owners attempted to bring Rusie and Freedman together, fearing, correctly, that Rusie’s absence would severely curtail attendance at New York games. Ostensibly the other owners backed Freedman but were angered when he said things like “some of the magnates want to prostitute the game for the sake of a few paltry dollars. They are in dire financial straits and think that Rusie will help them out as a drawing card.” [24] When the 1898 season came around, Rusie agreed to sign only after a group of owners got together and paid Rusie’s legal and “other” costs that he incurred the previous year. Such actions, coupled with a losing team, engendered universal hostility from the world of baseball toward the Giants owner. [25]

Freedman saw no reason to reward either Seymour (25-19, 3.18 ERA) or Amos Rusie (20-11, 3.03 ERA) for their 1898 performances. Rusie choose to retire, [26] and Seymour held out for the first month of the season. On May 11, 1899, Cy signed for $2000, five hundred dollars more than he received the previous season. [27] Playing for a dispirited Giants team that was to win only 60 of 150 games, he was able to compile a 14-18 record with an ERA of 3.56. He still finished second in the strikeout race with 142, only three behind Frank “Noodles” Hahn of Cincinnati. He ended the season leading the league in strikeouts per game (4.76) and was the fourth best in the opponents’ batting average (.245) and fewest hits per game (8.28) categories.

Seymour’s pitching career spanned, for all practical purposes, the three years from 1897 to 1899. Leading the league in both strikeouts and walks and averaging more than 300 innings per season evidently took its toll. In 1900 he appeared in only 13 games. Historian David Quentin Voight claims that: “Seymour was converted to an outfielder because of his penchant for free passes.” [28] Seymour did walk 655 batters and fanned 584 in his career. This is perhaps a deplorable ratio by today’s standard. However, if one examines the records of Seymour’s pitching peers, the strikeout to walk ratio of many of them is not that dissimilar. Hall of Fame teammate Amos Rusie, for instance, struck out 1934 batters in his career and walked 1704. Doc McJames, who nipped Seymour for the strikeout crown in 1897 and finished a distant second to Cy in 1898 and had a similar pitching career to Cy’s (79-80, 3.43), walked 563 and struck out 593 in his six years in the majors. Even the premier pitcher of the day and another Hall of Fame pitcher, Kid Nichols, walked 733 batters and struck out 875 between 1892 and 1900. [29] Cy Young, on the other hand, was not so wild, yet batters hit .271 when they faced him during this period in contrast to an approximate .240 average against the left-handed Seymour.

The batting differential should not be readily dismissed. The historic move of the pitcher’s mound from home plate to its present 60 feet six inches in 1893 created throughout the 1890s a hitters’ paradise in the National League. The average for the 1893-1899 period was .307! [30] Seymour’s ability to hold the opposing batters to 67 points below the league average is notable. During the three-year span from 1897 to 1899, Cy Young gave up 1146 hits in 1080.1 innings (1.093 hits per inning) whereas the lesser-known Cy allowed only 814 hits in 902.2 innings (0.901 hits per inning). His 8.30 hits per game was second only to Hall-of-Fame pitcher Vic Willis for the 1893 – 1900 era, better than Rusie or Nichols. None of this, of course, is to argue that Seymour was a better pitcher than Young or Rusie or Willis or Nichols; it is only to stress that he was, for three seasons, a member of an elite fraternity of pitchers. Seymour’s wildness was partially offset by his superb ability to strike out batters and severely limit their hitting.

Two other pitching differentials should not be ignored: the modern-day foul ball rule was not yet enacted and the pitching workload was markedly reduced from pre-1893 expectations. The pitching workhorse of the National League from the three seasons leading up to the mound change, “Wild Bill” Hutchison, led the league in innings pitched with near or above 600 innings per season and fell to approximately one-half of that average for the next three seasons. The lack of a foul strike rule, which curtailed pitchers’ ability to strike out batters, and the movement of the mound, (plus our contemporary reluctance to give up walks) begins to suggest why Seymour’s record may be unappreciated. Certainly in our era of the long ball, the base on balls is anathema to effective pitching. A century ago, when teams played for a single run, the walk was of less concern to baseball strategists. A Sporting Life report of a 6-2, four-hit victory serves as an example of how Cy’s wildness may have been used for positive results when it stated: “Seymour was wild at times, [but] was effective at critical moments.” [31] Hall of Famer Elmer Flick maintained that the best pitcher he ever batted against, when he was right was Seymour who ” . . . was practically unhittable. Cy had a wonderful control of his curve ball.” [32]

All players are subject to the limitations of the conventional wisdom of their particular era. An excellent relief pitcher today would have been nobody in particular fifty years ago. Roy Thomas, a thirteen-year Punch-and-Judy hitter (mostly with Philadelphia from 1899 to 1911) gained a reputation for fouling off pitches; once a reported 22 consecutive times. [33] It is doubtful that even in an era such as ours, with its pitch-count mantra, his fouling ability would be appreciated.

Pitching for mediocre and dispirited New York Giants teams, Seymour had established himself as a premier pitcher in an age of hitting prowess. That his pitching career effectively came to an end in 1900 had more to do with an apparent arm injury than his wildness. Indeed, Cincinnati pitcher Ted Breitenstein warned Seymour not to continue using the indrop ball (screwball) because it would leave his arm “as dead as one of those mummies in the Art Museum.” [34] Perhaps he injured his arm in spring training, but a few days before the regular 1900 campaign began he found himself playing centerfield for the “Second Team” in an intra-squad contest. [35] Just two days prior to the season opener the New York Times indicated that: “Manager (Buck) Ewing will give particular attention to Seymour” [36] to determine if he would be the opening game pitcher since the reluctant Amos Rusie had failed to report. [37] However, Cy did not get his first start until the 8th day of the season when he was shelled; he was lifted in the second inning after he gave up four runs, signaling that something was indeed wrong. The New York Times said of his performance, “the great southpaw proved a dismal failure.”

In the middle of May in Chicago he started another game but was unable to find the plate and was shifted to centerfield after giving up 10 runs in six innings. He collected two singles in the 10-8 loss. The next game in St. Louis he was inserted into the line-up as the left fielder and again hit safely twice but made two errors in a 13-5 defeat. [38] He disappeared from the line-up except for a couple of mop-up appearances in which he was also hit hard. [39] He finally won his first game of the season in early June, a 10-3 victory over St. Louis; ironically it was announced that very day that he was to be farmed out to Worcester and that Dick Cogan from Chicago had been secured in a trade. Then, mysteriously, the Times reports that “Si [sic] Seymour put in his appearance again at the Polo Grounds yesterday having been refused by the Worcester management as unfit. It is likely some deal will be fixed up for his retrading [sic] with Chicago.” [40] He played briefly with Charlie Comiskey‘s Chicago team, and suggestions were made that perhaps he would devote his time to playing the outfield although one newspaper report blames “his prancing about in the gardens”(outfield) as the primary reason for his lost pitching ability. [41] He even had time to pitch for the Scoharie Athletic Club against the Cuban X Giants on August 24, 1900. [42]

Yet by the end of the season he was still on the Giants’ reserve list [43] as a pitcher, although Andrew Freedman was suspicious of Seymour’s “habits” and demanded that team manager, William “Buck” Ewing, discover exactly “what he is doing. If there is not a change in him, and it is due to his habits, he [Seymour] will be laid off.” [44] This would not be the only time that his “habits” would be noted. A drinker? A narcotics user? It is known that he also suffered from severe headaches. [45] Occasional reports of bizarre behavior find their way into the sporting pages, like the time in 1906 he was mysteriously sent home from spring training because it was simultaneously reported that (a) he had a bad cold, (b) needed to rest his tired muscles because the southern climate did not agree with him, and (c) he needed to attend his ill wife. Or the time he was coaching third base for the Orioles and he decided to tackle a runner who ran through his stop sign. Or a report of him being removed from a game because he was inebriated.

By 1901 he was no longer a pitcher and had jumped to John McGraw‘s Baltimore Orioles to become the team’s right fielder. McGraw had been impressed with Seymour’s toughness as a pitcher, remembering how in two days in 1898 Seymour had started for the Giants and pitched three games against the Orioles. He lost the first game in the Polo Grounds, 2-1, and the first game of a double header the next day in Baltimore by the identical score; he finally beat the Orioles in the nightcap, 6-2. McGraw, years later, said of the feat that no player, not even “Iron Man” Joe McGinnity deserved the title “Iron Man” more than Cy Seymour. [46] Perhaps it was this determination and his good batting eye that convinced McGraw that Cy could be made into a good fielder.

The first seasons of the new century saw Seymour emerge as a star, batting .303 with the Orioles in 1901 and then following the infamous break up of the Baltimore team in 1902 going to Cincinnati where he became the regular center fielder posting batting averages above .300 (.369, .305, .342 and .313) culminating with the NL title of .377 in 1905.

In 1905 no batter, not even the great Honus Wagner, could match Cy’s batting accomplishments. Throughout much of the season Wagner lagged a few points behind Wagner. Both players met in a season ending doubleheader. A newspaper account that would be slightly reminiscent to today’s readers of the head to head battle between Sosa and McGwire nearly a century later reported ” . . . 10,000 were more interested in the batting achievements of Wagner and Seymour than the games…cheer upon cheers greeted the mighty batsmen upon each appearance at the plate and mighty cheering greeted the sound of bat upon ball as mighty Cy drove out hit after hit. The boss slugger got 4 for 7 while Wagner could only get 2 for 7…” [47] allowing Cy to win the crown by 13 points. He was first not only in batting average but also in hits, doubles, triples, total bases, RBI, slugging average, production, batter runs, and runs created. He was also a close second in home runs, runs produced and on-base percentage. His 1905 batting achievements served as a benchmark for his era; his .377 average was the best in the National League from 1901-1919; his slugging average of .559 was the best until Gavvy Cravath‘s .568 in 1913; his 121 RBI were tops until Sherry Magee drove in 123 in 1910; and his 40 doubles was the most ever hit by any National League outfielder until Pat Duncan collected 44 in 1922.

The first decade of the twentieth century brought the coterminous development of “scientific baseball” [48] and Deadball baseball. Another new feature was the hit and run play. A standard practice of the day was for batters to move to the front of the batter’s box in an attempt to hit the ball before it began to curve. Seymour eschewed this common practice, staying back in the box [49] and waving his bat around [50], stating that it allowed him to “get that much more time to be sure which infielder is going to cover second base. A large portion of my base hits were made in this way.” [51] He also used a wide variety of bats, depending on the pitcher—a highly unusual practice at that time. He used a light bat when facing a location pitcher and a heavier one when he was up against a fireballer. [52] Ned Hanlon, the Brooklyn manager, seemed to sense Cy’s unorthodox approach said, “I look upon Seymour as the greatest straight ball player of the age, by that I mean he is absolutely all right if you let him play the game in his own way. But if you try to mix up any science on him you are likely to injure his effectiveness.” [53]

A lifetime .303 hitter, Seymour batted above .300 from 1901 through the 1905 season. During this period no player in the National League ever batted higher than Seymour’s batting crown average of .377 in 1905. [54] Even though his average slipped to .286 in 1906, it still left him 8th in the league and his .294 mark left him 5th in the batting race of 1907. [55] In 1906 The New York World listed Cy along with ten other notables, such as Christy Mathewson, Ed Walsh, Hans Wagner, Nap Lajoie and Roger Bresnahan as the best in baseball. [56] In 1909, when he became a part-time player, his .311 average left him atop of all the reserve players in the league.

From 1901 through 1908 (excluding 1902) [57], Seymour would consistently rank high among the League’s twenty offensive categories. Forty-one times of a possible 140 (29%) he ranked no worse than fifth best in the League. [58] Honus Wagner, who dominated the era like no other player, led with 111 of the possible 140 (79%). Hall-of-Fame outfielder Elmer Flick [59] was a league leader 62 times (44%). Another Seymour contemporary and Hall-of-Famer third baseman, Jimmy Collins, was to make the leader category only 19 times (13.5 %). [60]

Four of the eight years that Seymour was a premier outfielder his batting placed him within the top five batters of the league. Four times he was among the top five in both RBI production and hits. No batter in the National League, during the first decade of the twentieth century, exceeded Cy’s seasonal high average of .377 in 1905. In the American League only Lajoie and Cobb topped it. [61] His 325 total bases in 1905 also stood as the best in the National League from 1901 through 1919. In 1905 he missed winning the Triple Crown by one home run [62] when teammate Fritz Odwell hit a homer. Cy won the doubles, triples and slugging crown, plus the on-base average, which was probably a better indicator of power than the rare home run of the Deadball Era.

Why has Seymour been forgotten?

Aside from the daily newspaper accounts and the sporting trade papers, little has been written about Seymour. [63] (See index at end of article) A brief survey of the literature reveals that he was, according to Christy Mathewson, one of the best “batsman” ever; but alas he was also a wild pitcher and there is a dubious claim that he was a poor fielder (Rathgeber). Still another article, by Hertzel, points out that he made more errors in a single season (36) than any other outfielder since 1900. [64] Hertzel’s article, “Baseball’s Hall of Blunders,” is a flippant journalistic exercise, devoid of analysis, that fails to explain why seven of the eight players listed who committed the most errors by position played during 1900-1903 period. (The other was 1911). There was no mention that fielders wore small, unconstructed gloves nor that outfielders were positioned much closer to the infield and with the Deadball style of play attempted to catch many balls that would in later years drop in front of the fielders for a single. Nor did Hertzel mention that Seymour retired with a better Fielder Rating than Ty Cobb.

With regard to his fielding Mathewson mentions Seymour in his book, Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball From the Inside (ghosted by sportswriter John N. Wheeler), in connection with the infamous “Bonehead” Merkle game of September 23, 1908 in which the Giants lost to the Cubs, 4-2. Most baseball followers see the loss as the turning point in the 1908 pennant race. No need exists to elaborate on this famous incident other than to say that Merkle was on first base in the bottom of the ninth inning with the game tied when a batter singled in the apparent winning run. The crowd poured onto the field. Merkle failed to touch second. All hell broke loose and the game was eventually ruled a tie. From that day on, Merkle was known as “Bonehead.”

Eventually the Cubs and Giants met in a one-game playoff to determine the pennant winner. In the second inning Seymour lost a fly ball in the sun. The incident has reinforced his reputation as a poor fielder. The misplay allowed three runners to score. The myth was that Mathewson, just prior to pitching to Joe Tinker, had turned and motioned Seymour to play deeper (a peculiar thing for the pitcher to do, especially with a veteran outfielder) [65] and that Seymour refused to move. Mathewson, however, later denied suggesting to Seymour that he move back, stating: Cy “knew the Chicago batters as well as I did and how to play them.” [66] Mathewson also admitted that day that he “never had less on the ball in my life” and that Cy would have probably caught the fly ball 49 times out of 50. [67] In the clubhouse after the game Cy said to Matty: “I misjudged the ball. I’ll take the blame for it.” And he did; sportswriters looking for an easy story took full advantage of his supposed refusal to take direction from the demigod Mathewson.

But was he a poor fielder? He certainly was not a good fielding pitcher, committing 104 of his lifetime 252 errors on the mound. Yet it is hard to believe that John McGraw, his manager both in Baltimore and New York, would have placed him in centerfield if he believed Seymour was a liability. In fact, by 1904 Sporting Life was to claim that he “… is as speedy and graceful as ever in centre field and covers a world of ground out there more than any other centre fielder in the National League.” [68] Frank Selee, the Chicago manager, called Seymour “a marvel and a pleasure to watch” and was amazed at his range and ability to back pedal. [69] In 1907 he made a spectacular diving bare handed catch that was widely reported to have been the best ever seen in New York City. A comparison to some of his contemporaries indicates that he was certainly a better-than-average center fielder. His Fielding Runs is +58, almost identical with Ty Cobb’s 55, and Tommy Leach +53 and Fred Clarke‘s +61; it is better than Elmer Flick’s 24, or “Circus” [70] Solly Hofman‘s 28 or Dummy Hoy‘s +3 or Socks Seybold‘s +1 and much superior to Ginger Beaumont‘s -26 or Mike Donlin‘s -31. Of all the regular center fielders [71] playing in the National League in 1907 and 1908 only one, Roy Thomas, had a better lifetime rating, + 71, than Seymour. But making an error at an inopportune time seems to have established Seymour as a poor fielder despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, a condition that Bill Buckner (+121) would undoubtedly understand.

The Frank Merriwell “dime novel” stories written by William Gilbert Patten (Burt L. Standish was his pseudonym) sold over 125 million copies during the Deadball Era and certainly must be regarded as a contributing factor in the collective amnesia of baseball historical enthusiasts. The two hundred Frank Merriwell stories embodied the turn of the century [72] All-American boy, [73] who settled problems on and off the playing fields with his strong right arm. It was no literary accident that Merriwell was portrayed as a pitcher on the ballfield. Nor is it accidental that the Merriwell legend has become intermingled with Christy Mathewson’s accomplishments. Accounts of ball games in the Deadball Era, especially when space allotments were limited, are overwhelmingly disposed toward pitching rather than hitting. [74] In contrast, contemporary brief media reports tend to emphasize the home run.

Hall of Fame?

Many have attempted the impossible task of compiling lists of the best players ever. Some are the all-time versions, which are usually laden with recent performers; others attempt to categorize them according to specific eras. Almost no one mentions Seymour. Typically, Dewey and Acocella’s The Biographical History of Baseball fails to highlight him; Michael Gershman’s thoughtful piece, “The 100 Greatest Players,” that appears in Total Baseball ignores him, even in the Utility category which includes Jackie Robinson, Cool Papa Bell, Pete Rose and Robin Yount. SABR’s fine publication Nineteenth-Century Stars, which outlines the accomplishments of 138 players, and Baseball’s First Stars (153 players) fail to include Seymour. A recent SABR survey of the great players of the 20th century reveals of the 244 players to receive votes, Cy Seymour does not receive one vote! [75] David Voigt does include Seymour along with “Turkey Mike” Donlin and “Buck” Freeman as players passed over for Hall of Fame consideration in the 1895-1900 era. During that particular era he was primarily a pitcher, and for three of those years he ranked among the best in baseball. Yet he had the dubious privilege of pitching in an era when league batters were hitting at a rate of .282 (1897-99). It would not be until the Ruthian era of the 1920s that league averages would resume such heights. Then, in turn, he batted in the Deadball Era (1900-1908) when batters for the entire league averaged but .256. His peak batting career average was .054 above the league average for the 1901-08 period, almost identical to that of Sam Crawford (.052) and Elmer Flick (.058) His league leading .377 was .122 above the National League average in 1905. This differential would not be topped in the NL until Rogers Hornsby‘s stupendous mark of .424 in 1924 (.151 above league average).

Roger Bresnahan, whose career falls within the same time frame of Seymour, is rightly recognized for his versatility: the lifetime .279 hitter caught nearly 1000 games and played in nearly 300 in the outfield, just over 100 in the infield and made 9 mound appearances. Similarly Fred Clarke is recognized with Hall of Fame membership for not only being a .312 lifetime hitter but a manager as well. Yet Seymour’s 140 games on the mound and 1333 games in the outfield have been inexplicably ignored. [76]

Bill James outlines a formula for admittance to the Hall of Fame although he admits that it is an imperfect series of rankings for pitching or position players. [77] The perfect player would score 100 in this system; the average Hall of Fame player scores just 50. James states that one of the problems with his method is establishing cut-off marks. Using this flawed model, Seymour would score 40 points, a score higher than the following Hall of Fame players – centerfielder Lloyd Waner (39), third baseman Jimmy Collins (32) and shortstop Joe Tinker (22). Seymour arrives at this figure despite the fact that one third of his career was in the pitcher’s box and approximately two-thirds was in the batting box. Using the identical model but factoring in a one-third/two-thirds ratio, Seymour scores 43. Yet many of the standards favor, as Bill James indicates, cumulative accomplishments and do not allow for the diversity of a pitcher turned outfielder. For instance, Seymour receives one point for his 1723 hits whereas Jimmy Collins’ 2000 hits gives him 3 points (1 point for every 150 hits above 1500). [78]

James’ all-time best-ranked player is surprisingly not Babe Ruth (81) but Willie Mays (84); in fact, Ruth also trails Christy Mathewson (83). But if Ruth’s pitching stats were factored in, he would score an astounding 116 points. If he were to be graded in this way, he would have to receive the mythical A+ rating – certainly a more suitable representation of his talents than the “81 points.” Ruth was at least an excellent pitcher along with being an outstanding positional player whereas Mays and Mathewson were “merely” outstanding in the field or on the mound. Similarly, Seymour was at least a good pitcher, perhaps even a very good pitcher (B to B+), and a very good positional player (B+). Yet the versatility of both Ruth and Seymour is ignored. With regard to Ruth it matters little since he was the pre-eminent player of the game. However, baseball enthusiasts seem to regard Ruth’s record as an aberration. The fact is, since 1893, that only one player other than Ruth has pitched very effectively in three seasons and hit very well in eight. [79]

McGraw and Seymour

McGraw is generally credited with the hiring of major league baseball’s first full-time coach, Arlie Latham. A long-time friend and former Oriole teammate of McGraw, Latham owed his good fortune indirectly at least to Seymour, and conversely Arlie was to influence Cy’s career.

In the days prior to the hiring of a full-time coach, players took to the coach’s box. Seymour was coaching one day when Harry McCormick attempted to stretch a triple into home run and ran through Cy’s hold-up sign, whereupon Cy proceeded to tackle McCormick. The surprised McCormick scrambled to his feet and was still able to score. When McGraw inquired about Seymour’s bizarre behavior, Cy offered a feeble excuse about the sun being in his eyes. From that moment on, according to Christy Mathewson, McGraw realized the need for a full-time coach. [80]

Latham was, in the opinion of Fred Snodgrass, “probably the worst third-base coach who ever lived” [81] and seemed to ingratiate himself to McGraw with a variety of practical jokes apparently designed in the now time-honored belief that such measures keep a bench “loose.” During spring training of the 1909 season, Cy took exception to a Latham prank and beat him up, causing McGraw to suspend Seymour from the team for eight weeks. [82]

Seymour received a career-altering injury in the first inning of the first game that he re-appeared in the Giants line-up. Chasing a long fly ball, he collided heavily with his right field teammate, Red Murray, and lay motionless for five minutes. He appeared to have recovered and thus resumed his position in center field. The next Boston batter sent him a fly ball, which he caught, and as he prepared to throw the ball home (there was a runner on third) he collapsed and had to be carried off the field. [83] The injury to his leg, according to Mathewson, curtailed his effectiveness for the remainder of his career. [84] Exactly two months after the injury he was able to play a few innings in left field in a game in Brooklyn, [85] but speedy Cy (he averaged 20 steals per year) was never the same player after the accident.

McGraw does not mention Seymour in his autobiography, My Thirty Years in Baseball, perhaps because of the Latham incident. Yet McGraw appreciated his toughness and had the foresight to place him in the outfield when his pitching career came to an end.

Personality

It is difficult to assess Seymour’s personality from the snippets of data available. Veteran catcher Duke Farrell relates an explosive emotional experience when Cy first started to pitch for the Giants. In Chicago the rookie pitcher was sailing along effectively until the 8th inning when he suddenly became very wild giving up nine runs and in the parlance of the day “ascended into the air.” His cheeks turned red, he threw his hat off after a bad pitch, and then threw his glove away after another. “Finally”, Farrell states, “Cy was worked up to such a state that after making a pitch he would run to the plate and grab ball out of my hands, hustle back and without waiting for my sign shoot it back…Nine Chicago runners crossed the plate [before the inning was over]…Seymour subsequently had many aerial flights, but nothing like his Chicago performance.” [86] He was not only excitable and high-strung; he dressed differently than his teammates and apparently was aloof. All these are characteristics that would give some fans, sportswriters and ball players the chance to jeer him at the first opportunity.

There is one well-reported incident of Seymour’s being removed from a game because he was inebriated; yet a follow-up report suggested that the incident was isolated and that he then played like “a whirlwind.” [87] Another said: “J. Bentley Seymour by his good batting is more than making amends to the Reds management for his one jag”. [88] In another incident, The Cincinnati Post complained to the Reds owner, August Herrmann, that Seymour threatened a photographer from the Post. [89] Reports by Mrs. McGraw and Hans Lobert [90] indicate that Seymour was a hard-playing, hard-drinking player. One might therefore surmise he was prone to alcoholic binges and leave it at that; on the other hand, it’s possible that he simply saw himself as different. In a world that was determined to be right-handed he was very much left-handed. Conventional wisdom of the day often forced left-handed school children to write with their right hand. Similarly baseball, at the time, could not see left-handed pitchers to be equal to right-handed ones. He was unorthodox; his pitching and his hitting were contrary to the norms of the day.

Seymour seemed sensitive about his name and came in for a good deal of chiding because he insisted that he was related to the Duke of Somerset. [91] He apparently insisted upon being called J. Bentley or James Bentley rather than the nickname Cy (for Cyclone) that New York sportswriters gave him. He had at least three publicized altercations during his career – an off season brawl with the ball playing brothers Jessie and Lee Tannehill, [92] the Latham affair and a punch-up with Cincinnati pitcher teammate, Henry Thielman, during an exhibition game in Indianapolis. Thielman, according to the report, “kidded” Seymour about his name. [93] On the other hand, he was apparently the person who applied the nickname “Tillie” on Arthur Shafer. Mrs. John McGraw describes the day in 1909 when her husband introduced the shy, good looking young Shafer to the Giants in the Polo Grounds clubhouse:

“Big Cy Seymour, an Oriole in word and deed, responded first with ‘We’re all damned glad to meet you Tillie!’ Then came the chorus! Yes sir, Tillie glad to see you. Yes sir, Tillie glad to see you. Make yourself home, Tillie! Goood Luck, Tillie…Save Your Money Tillie…Get the last bounce Tillie.” [94] Another report of the same incident has Seymour rushing over to Shafer and planting a kiss on Shafer’s cheeks saying “Tillie how are you?” Shafer hated the nickname, but it stuck with him. [95] One might imagine that this incident coupled with the Latham episode paved the way for Seymour’s departure to obscurity [96] and may be one of the reasons that John McGraw ignores Seymour in his book My Thirty Years in Baseball. Yet while playing for Baltimore of the Eastern League in 1911 an opponent, former major leaguer Bobby Vaughn, said that he still had the best batting eye of anyone in baseball. Certainly an exaggeration, but the 39-year-old did hit .306 that year, and one is left to speculate that McGraw and others may have not chosen to employ Cy because of his peculiar personality traits. Vaughn lavishly praised Cy but then curiously added “Many think him a shirker but he is not…Seymour is a conscientious ball player whatever else may be said…” [97] He was also plagued by headaches. In the winter of 1904-5 he sought nasal surgery in an effort to solve his problem. [98] Migraines? Occasionally he would exhibit strange behavior like the morning that he decided to take on a lion at the zoo. Mental illness? Some reports later said he was drunk, which was probably so, but he would not have been the first person to use alcohol as a cover up of other problems.

On the other hand, there are reports that Seymour was “as straight and clean as the Bank of England” [99] and unlike some other players, he never took advantage of owner Hermann’s generosity. Hermann attended Seymour’s wedding [100] and added $100 a month to Cy’s $2800 contract when he arrived from Baltimore and arranged an off season “job” which according to a newspaper report required him to do little more than walk the streets clad “in swell clothes.”

Cy certainly seemed the dandy. Sprinkled throughout the Seymour scrapbooks that reside in the Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown are accounts and pictures, some of them mocking, about Cy’s sartorial splendor. Like many athletes, then and today, he often seemed to take himself too seriously. Be it his dress or his insistence that he be referred to as J. Bentley [101] rather than Cy or his reluctance to be photographed, he very much seemed the prima donna.

The 1906 trade (sale) of Seymour from the Reds to the Giants for $10,000 was the largest in baseball history to that time [102]. After playing but one game for the Giants in which he made a sensational catch, he demanded that he receive a portion of the $10,000 that he insisted that Garry Herrmann, the Reds owner, promised him if the sale was completed. Herrmann denied that a promise had been made. Cy threatened to go on strike. John McGraw was able to convince Seymour to reconsider and Organized Baseball may have avoided a precedent [103] similar to professional soccer in which a player transferred from one club to another receives a percentage of the transfer fee.

Seymour was not devoid of humor. Upon his first return to Cincinnati in a Giant uniform after the trade he wore bright red false whiskers as a disguise that allowed him to receive front-page headlines in The Cincinnati Post. Descending from the team carriage the bewhiskered Cy announced to the multitude, “Cy Seymour I am pained to relate, ladies and gentlemen, is not coming to the park today. He is afraid that the Cincinnati fans will lynch him”. When he grounded out his first time at bat, he was jeered and cheered by the local fans. [104]

The only remaining correspondence [105] written by Seymour are two job enquires made to Hermann regarding managerial positions in 1913 or thereabouts. A letter written on November 28, 1913, gives some insight into the character of the man. He saw himself as a loner but capable of making managerial decisions without being influenced by the press or hangers-on. His letter also suggests that he may have been regarded as an odd character because he told Hermann: “I may seem funny to you the way you know me. I am different on the inside than on the out & I know if I had half a chance I will make good. I am not much of a talker & [don’t] go around talking about myself.” [106] On the other hand his letter suggests that Hermann be wary of baseball writers’ opinions and is bold enough to say, “I am going to give you a tip now and always remember it. It takes [two] to run a ball club. The manager and yourself…” [107] What Hermannn thought of the tip we cannot be certain except that Cy did not get the job and found himself at age 41 effectively out of organized baseball.

Typical of aging stars of the day, Cy played minor league ball in 1911 and 1912 for Baltimore and Newark. A newspaper report of his release in Baltimore stated, “Although he played good ball his habits were such that it was decided that he would no longer play on the team.” [108] Apparently able to correct himself, at age 41, he was to make it briefly, albeit unsuccessfully, back to the major leagues with the Boston Braves in 1913.

Seymour apparently contacted tuberculosis while working in the shipyards of New York during the First World War. He died in New York City on September 20, 1919. His death was over- shadowed by the talk of the World Series involving Cincinnati and the now-infamous Black Sox. One obituary claimed that he worked on the docks because he was unfit for military service. [109] Yet he was able to play 13 games for Newark in the International League during the 1918 season when he was 46 years old. It might be assumed that he was an alcoholic; he was also rumored to have been penniless [110].

Sporting Life said of Seymour “that he was one of the most brilliant though erratic pitchers the game ever produced” [111]. Christy Mathewson said that he “was a mighty batsman … one of the best ever.” [112] John McGraw thought he deserved the title of “Iron man.” Former slick fielding second baseman turned sportswriter Sam Crane wrote in the New York Journal that Seymour “proved himself to be one of the best outfielders in every department” and that Cy “put to rest the notion that pitchers could not hit well.” [113] Now he is all but forgotten – the victim of being a pitcher in a hitters’ era and a hitter in the dead ball era. His burial was a simple one, his boyhood chums acting as pallbearers, and although a large throng attended the service, no one from organized baseball did. [114] A search of the rural cemetery in his hometown of Albany, New York, serves as a final irony. He is buried in the family plot, but no stone marks the accomplishments of the second most versatile player that the game has ever known. [115]

An earlier version of this article appeared in SABR’s Baseball Research Journal #29 (2000), 3-13.

Last revised: February 9, 2023 (zp)

Sources

I owe thanks to many people who offered assistance with my research. They are: Bill Weiss, Bob Hoie, Larry Gerlach, David Mills, George Gmelch, Sharon Gmelch, Terry Malley, Jean Ardell, Darryl Brock, Bob Klein, David Voight, Jerry Malloy, Tim Wiles and the personnel at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown.

In addition to the sources mentioned in the endnotes, I made use of the following:

Al Demaree, “Tough Customers”, Collier’s, May 14, 1927

Bob Hertzel, “Baseball’s Hall of Blunders”, Baseball Digest, January 1973

Christy Mathewson, “‘Outguessing’ the Batter”, Pearson’s Magazine (American Edition), May 1911.

Christy Mathewson, Pitching In A Pitch: Baseball From the Inside, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NB, 1994, pp.304.

Bob Rathgeber, “When Hitting Became a Science: Cy Seymour,” Cincinnati Reds Scrapbook, 1982

Notes

[1] Thanks to Tom Ruane for this information. He reports that 13,561 have played ball from 1893 until through the 1998 season.

[2] David Nemec, Great Baseball, Feats, Facts & Firsts, Signet Sports, New York, NY, 1989, p.331.

[3] See Total Baseball: The Ultimate Encylopedia of Baseball, edited by John Thorn and Pete Palmer, HarperCollins, New York, 1993, pp. 1932-3.

[4] Harold Seymour, Baseball: The Golden Age, Oxford University Press, New York, NY, 1971, p122.

[5] It should be noted that the umpire could declare a strike if he believed the batter was deliberately attempting to foul a pitch. Also home plate was until 1900 a 12-inch square when it changed to a pentagon measuring 17 inches across. Also beginning in 1894 foul bunt attempts were strikes.

[6] Prior to 1893 Al Spalding (252 wins and 613 hits), Hoss Radbourne (309 wins and 585 hits) Scott Stratton (97 wins and 379 hits) posted significant pitching and hitting record yet none of them had two distinctive careers. Only the great John Montgomery Ward (164 wins and 2105 hits) was able to challenge the accomplishments of Ruth and Seymour. And although Ward played until 1894 he was an infielder for the last 10 years of his playing career. Thanks to Larry Gerlach for pointing this out to me.

[7] See The Times-Union, Albany, NY, September 21, 1919. An unusually large salary considering that he only made $2000 playing for the Giants in 1899! The report indicates that the Northern New York League was supported by millionaire sportsman, Harry Payne Whitney. Prior to playing in the NNYL Seymour played for the Ridgeway team in his hometown of Albany, NY.

[8] Seymour Scrap Book, 1896. These eight volumes contain comprehensive press clippings of Cy’s career apparently compiled by his mother or father. Arranged in a fastidious chronological order that is only marred by the fact that the name and date of the publication has been eliminated by the compiler. My guess is that his father, Theodore, was the compiler. Correspondence from a Baltimore publisher to Theo. Seymour appears in Scrapbook 1908. Thus future reference to the scrapbooks shall read as e.g. SSB 1897 except when the exact date or name of the publication is known.

[9] New York Times, September 5, 1897..

[10] The New York Times report does not jibe with Adam Rusie’s view. Rusie took Seymour under his wing in Cy’s rookie season and reported that Seymour was “a willing youngster and a good pupil”. See Amos Rusie file, HOF, “Fireball Rusie… Tells How He Held Out…”

[11] New York Herald, September 19, 1897.

[12] Total Baseball has him at 18-14 while Bill Weiss’s stats have him at 20-14. Personal correspondence Weiss to Kirwin, November 1998.

[13] See p. 1920 of Total Baseball, edited by John Thorn and Pete Palmer, 3rd Edition 1993.

[14] Again, Weiss has him at 25-17.

[15] Boston Manager Ed Barrow once said, “I would be the laughing stock of the league if I took the best pitcher in the league [Ruth] and put him in the outfield”. See The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball by Jonathan Fraser Light, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 1997, p.579

[16] Sporting Life October 15, 1898

[17] “Cy Seymour’s Pitching Arm”, HOF SB July 27, 1898 Sam Crane, among others seemed to think his small hands was an important factor causing his wildness.

[18] Seymour’s walk-to-strike-out ratio was 655/584. Rusie was 1704/1934 and Nichols 1268/1868.

[19] A typical 1898 victory saw Seymour throw a four hitter and collect two hits and score one run himself in a 6 -2 win over Cleveland on May 30th, striking out seven and issuing as many walks.

[20] Nichols who had five shutouts, one three-hitter, one four-hitter and six five-hitters.

[21] HOF SB 1898

[22] He also again led the league in walks with 213.

[23] James D. Hardy, Jr., The New York Giants Baseball Club, The Growth of a Team and A Sport, 1870 – 1900, McFarland & Co., Jefferson, NC, 1996, pp. 157-161.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Seymour himself experienced Freedman’s parsimony when as a rookie he was fined $10 for leaving a ticket booth that he was occasionally required to man in order that he might watch his teammates play!

[26] He did return to MLB in 1901 to pitch in three games for Cincinnati. In exchange for Rusie, Cincinnati sent the Giants an obscure young pitcher, Christy Mathewson!

[27] New York Times, May 12, 1899. It is of note that Freedman said a year earlier he would not trade Seymour for $10,000.

[28] David Quentin Voight, The League That Failed, Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Md., 1998, p. 123.

[29] Cy Young, of course, was a notable exception; although his won-loss record (72-48 v.57-51) was not radically different from Seymour’s during the 1897-99 seasons, Young walked only 134 batters during the three years in question, seventy-nine less than Cy during the 1898 campaign alone! On the other hand, Young, who had won the strikeout crown in 1896, only managed to strike out 300 batters from 1897-99 while Seymour struck out 534 in the same period.

[30] Voigt, p.141. The average did drop to .281 for the years 1897-99.

[31] Sporting Life, June 4, 1898.

[32] HOF SB 1902 Flick added ‘I have asked many baseball players who batted against him the days past, and they all agreed that he was the star of them all when in condition”

[33] Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encylopedia of Baseball, McFarland, Jefferson, N.C., 1997, p.276.

[34] HOF SB 1898.

[35] New York Times, April 8, 1900.

[36] New York Times, April 17, 1900.

[37] New York Times, April 19, 1900.

[38] See New York Times, May 16 & 18, 1900.

[39] New York Times, May 19 & 29, 1900.

[40] New York Times, June 12, 1900; see also June 8, 1900.

[41] HOF SB 1900.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Historian Bob Hoie hypothesizes that Seymour probably injured his arm or attempted to take something off his pitches to improve his control and that the Giants merely suspended him because of his arm problems. Personal correspondence Hoie to Kirwin December 28, 1998. Also David Voigt in personal correspondence reflects a changed opinion regarding the pitching demise of Seymour believing that it now had probably more to do with his arm problems than wildness. Personal correspondence Voigt to Kirwin undated 1998.

[44] Andrew Freeman to William Ewing. May 21, 1900; see James Bentley “Cy” Seymour file, Hall of Fame Research Center, Cooperstown, NY.

[45] Sporting Life, ” The disappearance of ‘Cy’”, March 11, 1905.

[46] See HOF Seymour file clipping “Cy Seymour’s Iron Man”. See also New York Times

[47] HOF SB 1905.

[48] The use of the bunt, hit-and-run, Baltimore chop and cut-off man developed by Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon.

[49] Bob Rathgeber, “When Hitting Became A Science”, p. 36.

[50] Sporting Life, January 6, 1906.

[51] Ibid., Rothgeber

[52] Ibid.

[53] HOF SB 1905

[54] Only the great Nap Lajoie’s .426 during the 1901 American League season exceeded Seymour’s mark.

[55] Even in his last year as a regular player his .267 average place him in 13th spot.

[56] New York World September 22, 1906. The other five were Art Devlin, Giants, George Stone St. Louis, Johnny Kling Chicago Americans, Hal Chase New York Highlanders and Rube Waddell, A’s.

[57] During the 1902 season he ranked high in both RBI and HRs in the combined league totals.

[58] If one wanted to stretch the case the claim could be made that Seymour had the fourth highest number of home runs in 1904. The number is correct; however, six players had more home runs that he did. A similar case could be argued for 1906 Triples. I choose the more rigid interpretation of including only the top five players wherever possible.

[59] Since 1907 was Flick’s last year as a regular player, the 1900 season, his second best in category leadership (14), was used for comparison purposes. In 1902 his name does not appear in any of the categories. In the 1901 through 1907 seasons Flick’s category percentage would drop to 34%.

[60] 1897 through the 1904 season, excluding the 1902 season when he only played in 108 games.

[61] Lajoie hit .426 in 1901 and .384 in 1910. Cobb equalled Seymour’s .377 in 1909 and batted .383 in 1910.

[62] His teammate, Fred “Fritz” Odwell, was also a converted pitcher who hit nine of his ten career home runs in 1905. See Albert Flannery’s poem “Odwell’s Run” in The National Pastime, Number 15, 1995 p. 96.

[63] Even the trade of 1906 from the Reds to the Giants for $12,000(some reports claim it was $10,000) was the largest in baseball history up until that time has been ignored.

[64] Bob Hertzel, “Baseball’s Hall of Blunders”. Baseball Digest, January 1973.

[65] See Rube Marquard, The Life and Legend of a Baseball Hall of Famer. McFarland, Jefferson, N.C., 1998 p. 51.

[66] Christy Mathewson (John N. Wheeler) Pitching in a Pinch: Baseball From the Inside. University of Nebraska, Lincoln, NB, 1994, p. 186.

[67] Ibid. pp. 186-188

[68] Sporting Life in “National League News” June 18, 1904.

[69] Seymour HOF SB 1902

[70] Arthur Frederick Hofman was well known for his circus catches and was named after a comic strip character. See James A. Skipper, Baseball Nicknames, McFarland, 1992, p. 127.

[71] See Total Baseball, 3rd edition pp 2327-30. Does not include players who did not play at least 300 games in the outfield.

[72] Ironically the first Merriwell stories appeared in 1896, the rookie season of Seymour.

[73] For an excellent treatment of this subject see William Curran’s Strikeout: A Celebration of the Art of Pitching, Crown (Random House), New York, 1995, pp. 119 -129.

[74] A typical one-sentence synopsis that appeared in Sporting Life of a game played on April 24, 1905 in which Cincinnati beat St. Louis 8 – 0 followed by a box score read: ” Hahn pitched his first game of the season against St. Louis today and showed excellent form, only one visitor reaching first base”. No mention that the Reds scored five runs in the top of the first and added two more in the top of the second or that Seymour paced the attack with two doubles.

[75] Of course one of the reasons that he was ignored may be that he was an outfielder in the 20th century and a pitcher in the 19th century.

[76] The left handed Cy also played five games at first base and two at second base and one at third.

[77] Eleven categories for position players (e.g. “1 point for each hit above 1500, up to a limit of 10 points”) and ten for pitchers (e.g. “1 point for a career win above 100…”) See Bill James, The Politics of Glory: How Baseball’s Hall of Fame Really Works, Macmillan, New York, 1994, pp. 172 – 84. See also James’ “What Does It Take?” in John Thorn’s The Armchair Book of Baseball, Macmillan, New York, 1985, pp. 173-180. Seymour would score 88 in a 100-point “must” system.

[78] Babe Ruth suffers from the same bias as Seymour. According to the standard he is three points behind Willie Mays (84) or two behind Christy Mathewson (83), yet if the Babe’s pitching were to be evaluated he would score 36 for pitching alone.

[79] Seymour stole 222 bases during his career. The 38 bases that he stole in 1901 were good enough for third place in the NL that year. For the next nine years he averaged twenty stolen bases per season even though he was a part-time player in 1909 and 1910.

[80] Mathewson, Pitching in a Pinch, pp 120-1.

[81] Charles C. Alexander, John McGraw, Bison Books, Lincoln, NB, 1988, p.143.

[82] New York Times, April 27, 1909.

[83] Ibid.

[84] Mathewson, Pitching in a Pinch, pp. 135-36.

[85] New York TimesJune 26, 1909

[86] HOF SB 1903 “Seymour’s Airship”

[87] Sporting Life, August 15, 1903. Another report, probably in a Cincinnati newspaper, said that he had called in claiming he was sick when in fact he was drunk requiring him to miss several games. The record indicates that he played in 135 of the 141 the Reds played that year.

[88] Sporting Life, August 29, 1903

[89] Ray Long to August Hermann, Seymour HOF file, January 31, 1906.

[90] Lawrence Ritter, The Glory of their Times: The Story of the Early Days of Baseball – Told by the Men Who Played It, Vintage Books, New York, 1985, p.192.

[91] “Seymour the Straight”, Seymour HOF file, November 17, 1906

[92] Reported, apparently in the Albany Times Union, in 1903 citing a Cincinnati dispatch stating that Seymour walked away unmarked from a battle with the two Tannehill brothers. They in turn both required hospital assistance. See Hof SB 1903.

[93] Sporting Life, October 11, 1902.

[94] Mr. John J. McGraw and Arthur Mann, The Real McGraw, David McKay, 1951, p. 227. Thanks to Darryl Brock for this source.

[95] James K. Skipper, Jr., Baseball Nicknames: A Dictionary of Origins and Meanings, McFarland, Jefferson, NC 1992, 252.

[96] Ironically Fred Snodgrass, who was to soon replace Cy as the Giants regular centerfielder, was also introduced that day.

[97] See HOF Seymour file “Bobby Vaughn talks of Cy’s Batting Eye”

[98] See “The disappearance of Cy” in Sporting Life, March 11, 1905.

[99] “Seymour the Straight”, Seymour HOF file, November 17, 1906.

[100] Sporting Life, December 27, 1902

[101] He picked up the name Cy when he first arrived in New York. The name referring to his pitching style derived from the word cyclone and was a rather common sobriquet applied to pitchers of the day. He may have wanted to put his pitching days behind when he resisted being called Cy, yet on the other hand it may have been simply to clarify the fact that he was not a Jew. A letter to the New York Globe asks “…is Seymour a Hebrew or an Irishman?” and receives the following answer. “He is an American of English descent.”

[102] Some reports indicated that it was $12,000

[103] Seymour certainly seemed to be not unaware of the upcoming sale, openly saying to the press “Tell ‘Em I’m going Away.” Whether by design or preoccupation, his indifferent play prior was reflected in his .257 batting average.

[104] HOF SB 1906 Cincinnati Post August 25, 1906

[105] See “Cy Seymour in Disgrace” HOF SB 1903

[106] Seymour to Hermann, HOF File, November 28, 1913.

[107] Ibid.

[108] HOF SB 1908. This scrapbook contains several items after 1908.

[109] New York Times, September 22, 1919.

[110] Bob Rathgeber, Cincinnati Reds Scrapbook, JCP Corp, Virginia Beach, Va, 1982, p.37.

[111] Sporting Life, June 17, 1905

[112] See “‘Outguessing’ the Batter” by Christy Mathewson in Pearsons Magazine, May 1911

[113] HOF SB 1902

[114] Times-Union, Albany, September 23, 1919.

[115] Albany Rural Cemetery visit June 5, 1999. Thanks to the personnel at the cemetery.

Full Name

James Bentley Seymour

Born

December 9, 1872 at Albany, NY (USA)

Died

September 20, 1919 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.