Kirk Gibson

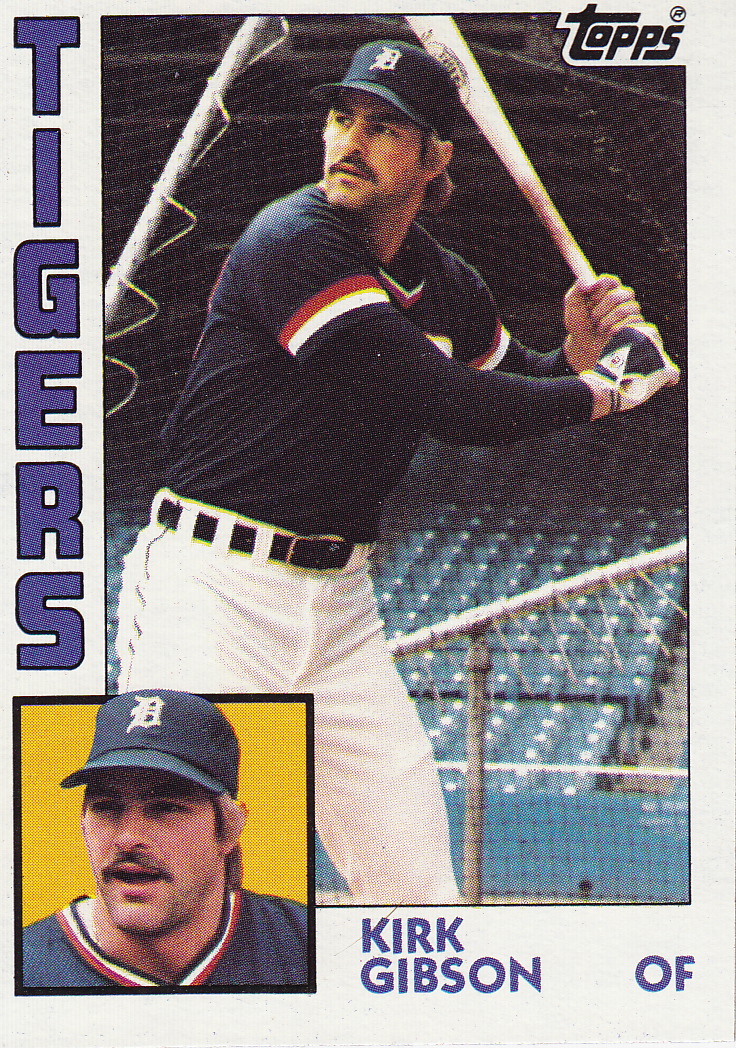

Immortalized by two dramatic World Series home runs, one in 1984 for the Detroit Tigers and another in 1988 for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Kirk Gibson was noted for his competitiveness and clutch hitting. Plagued by injuries, he never lived up to the hype created by his manager, Sparky Anderson, when he referred to Gibson as “the next Mickey Mantle.” However, Gibson did combine blinding speed with power capable of producing tape-measure home runs. He played baseball as if he were in a football game. As a hometown boy, Gibby (as he was known) had a strange relationship with Detroit Tigers fans. They either loved his fiery spirit and drive to win, or hated him for his arrogance, rude demeanor, and gruffness toward autograph seekers. But in the end they respected him and selected him in 1999 for the all-time Tigers outfield alongside legendary players Ty Cobb and Al Kaline.

Immortalized by two dramatic World Series home runs, one in 1984 for the Detroit Tigers and another in 1988 for the Los Angeles Dodgers, Kirk Gibson was noted for his competitiveness and clutch hitting. Plagued by injuries, he never lived up to the hype created by his manager, Sparky Anderson, when he referred to Gibson as “the next Mickey Mantle.” However, Gibson did combine blinding speed with power capable of producing tape-measure home runs. He played baseball as if he were in a football game. As a hometown boy, Gibby (as he was known) had a strange relationship with Detroit Tigers fans. They either loved his fiery spirit and drive to win, or hated him for his arrogance, rude demeanor, and gruffness toward autograph seekers. But in the end they respected him and selected him in 1999 for the all-time Tigers outfield alongside legendary players Ty Cobb and Al Kaline.

Kirk Harold Gibson was born on May 28, 1957, in Pontiac, Michigan. He was the youngest of Bob and Barbara Gibson’s three children. His father was an auditor for the state of Michigan and later became a math teacher at Kettering High School in suburban Waterford, where Kirk went to school. Barbara taught theater and speech at nearby Clarkston High School. Kirk admitted to being a mama’s boy growing up. Her calm, reassuring presence was a stark contrast to his father’s pressure to excel. His two sisters, Jocelyn and Christina, helped spoil him. As Kirk remembered it, “My parents never made me work. When I grew up, all we did was screw around with motorcycles and water-skiing. I had it pretty easy. My dad pushed me hard in athletics. He built me a home plate and mound in the backyard and a hoop over the garage, and he made me practice.” His father made him do drills and practice constantly, and Kirk appreciated the discipline and mental toughness it instilled when he became older. At the time, however, he began to almost hate athletics because of his father’s constant pressure. Kirk noted that his parents were always very supportive and never missed any of his games, and he proudly cited them as his role models and heroes. During high school, he spent the summers playing American Legion baseball — winning a state championship in 1975. In a foreshadowing of things to come, Gibson hit a game-winning home run to put his team into the championship round.

Gibson played football, baseball, and basketball as well as running track at Waterford Kettering High, but football was his true love. He had several outstanding games and as a senior was named All Oakland County in the fall of 1974. He was lightly recruited, so when Michigan State University offered him a football scholarship, he jumped at it.

In 1975, Kirk was determined to be a starter as a freshman at Michigan State. He tried to outwork, outhustle, and outplay everyone else on the team. For him, everything was a competition. He learned he was going to be starting at flanker and quickly called his parents with the news. The first game, against Ohio State, was an eye-opener as the Spartans fell 21-0. Gibson soon realized that the learning process never stopped and was more determined than ever to succeed. The following week he scored his first touchdown, helping MSU end Miami of Ohio’s 25-game winning streak. The Spartans finished 7-4 with Kirk catching four touchdown passes, including an 82-yard bomb in their season-ending victory over Iowa.

Gibson had his eyes set on a Rose Bowl berth, but his dreams were shattered when the Spartans were placed on three years’ probation in January 1976. The remainder of his football career was spent with no televised games and no hope for a bowl game. Additionally, the coach, Denny Stolz, was fired and Darryl Rogers took over the reins as football coach. Initially, Rogers thought about making Kirk an outside linebacker but decided his speed was needed on the offensive side of the ball. The team finished 4-6-1 in 1976, but Gibson had 39 receptions for 748 yards, leading all Big Ten receivers. The team responded to Rogers’ innovative offense and improved to 7-3-1 in 1977.

After his junior season, Gibson was approached by Michigan State baseball coach Danny Litwhiler about playing baseball. Gibson’s father had always wanted him to play baseball as well as football, and Rogers gave his blessing, telling Kirk it might give him some leverage in the NFL draft. To Gibson’s surprise, he thoroughly enjoyed playing baseball, and he attracted a lot of scouts with his power and speed. In his one year of college baseball, he batted .390, hit 16 home runs, batted in 52 runs, and stole 21 bases in 48 games. He established school records for homers and RBIs, and was selected to the All-American team in baseball. Gibson was approached by several major-league scouts and was touted as a possible first-round selection for the amateur draft. The Detroit Tigers invited him to come to Tiger Stadium for some batting practice. Gibson put on a tremendous display of power, convincing Tigers assistant general manager Bill Lajoie that Gibson was his No. 1 choice for the coming baseball draft. The Tigers had the 12th selection, and Gibson wanted to play for his hometown team. When teams with earlier picks than the Tigers inquired about his future plans, he made it clear that he would return to Michigan State for his final football season. Apparently the question marks loomed large enough that the Tigers were able to select Gibson with the No. 12 pick on June 6, 1978. His decision to play professional baseball surprised a lot of people. But for Gibson it came down to money and long-term goals. Baseball had free agency — which football at the time did not. The players had longer careers, and the benefits obtained through the players’ union were much better in baseball. A week after the draft, Gibson signed a six-year deal for $200,000 and reported to Class-A Lakeland in Florida. The contract contained a clause allowing him to return to Michigan State and play football, beginning approximately August 14, 1978.

Gibson’s first professional baseball manager was Jim Leyland. Leyland met him at the Miami airport and immediately set Gibson straight about who was in charge and what was expected of a raw rookie. Kirk responded as he always did; he took it as a challenge and worked hard on all facets of his game. And he developed a professional respect for Leyland and his approach to the game. Gibson played in 54 games with Lakeland, hitting .240 with eight home runs and 40 RBIs. He also struck out 54 times in 175 at-bats.

Gibson returned to East Lansing for his final football season. The team ended up co-champion of the Big Ten, setting a scoring record that lasted for 16 years. The team’s final record of 8-3 included a huge upset of Michigan, the co-champion. But the Spartans were still under suspension and could not play in the Rose Bowl. Kirk was named All-American as a flanker in football — and as an outfielder in baseball. He had set several Spartans career football records, including 24 touchdown catches, 112 receptions, and 2,347 receiving yards. He also had two touchdowns rushing. Despite his baseball contract, the National Football League’s St. Louis Cardinals drafted him in the seventh round in 1979.

During spring training in 1979, Gibson was invited to the major-league spring training camp. His display of power and speed attracted a lot of attention, and Kirk felt he had a good shot at making the major-league roster. He was devastated when he was assigned to Triple-A Evansville. He suffered a knee injury in his very first exhibition game with the minor-league team when he collided with another outfielder. He had arthroscopic surgery, and reported to Evansville after a month’s rehabilitation. There, Leyland, now Evansville’s manager, was waiting for him. Gibson’s numbers weren’t overwhelming — a .245 batting average, 9 home runs, and 20 stolen bases — but he heated up toward season’s end and helped the Triplets win their division and the playoff championship, hitting .429 with three stolen bases in the American Association playoffs. The day after the Triplets’ last game, Leyland told Gibson he was to report to the Tigers.

Gibson sat on the bench for the Tigers for three days before seeing any action. Finally, he persuaded manager Sparky Anderson to put him in as a pinch-hitter. It was a September 8 home game against the New York Yankees, and Gibson faced Goose Gossage. The score was 5-4 Yanks with the tying run on first base and two outs. Gibson managed to foul off the first two pitches before Goose blew a third strike by him to end the game. In Gibson’s first start, in right field on September 19, he got his first hit — a single off Baltimore’s Dennis Martinez — as part of a 2-for-4 day with a run scored. Less than a week after that, on September 25, Gibson hit his first major-league home run, off the Orioles’ Steve Stone. His brief time with the Tigers (.237 in 38 at-bats) was enough to persuade Anderson to put Gibson on the parent club in 1980.

Gibson began 1980 as the starting center fielder and was featured on the cover of Sports Illustrated as the “Rip Roaring Rookie.” The Tigers had a solid core of young players growing up together under Anderson’s tutelage. Gibson had a triple and home run in the season opener, an April 10 night game in Kansas City. Pinch-hitting for Rick Peters in the bottom of the ninth inning in the nightcap of a June 16 doubleheader at Tiger Stadium against Milwaukee, Gibson felt a pop in his wrist swinging at a changeup. Alan Trammell had to finish the at-bat. Gibson woke up the next day in severe pain. The team doctors could not find a problem, so the wrist was put in a cast to rest it. The injury resulted in a truncated season in which Gibson hit .263 with nine home runs. In August, he visited the Mayo Clinic, where doctors found the problem: an abnormal development in his arm bones. They shortened his ulna bone and inserted a steel plate. Gibson was told that he would need eight months of rehabilitation. There were no guarantees that the wrist would hold up or that Gibson would ever play baseball again. The irony was that the wrist injury would not have affected his playing football.

During spring training in 1981, Gibson tested the wrist gradually, waiting until nearly the end of camp to go all-out. His eagerness for the beginning of the new season was dimmed when Anderson inserted him into right field on Opening Day, April 9 against Toronto. Right field in Tiger Stadium was the sun field and was made even more difficult by the overhang of the second deck. Gibson had a tough first game, with a fly ball bouncing off his head after he lost it in the sun, and later he was charged with an error when he lost another ball in the overhang, to give the Blue Jays a 2-1 lead (Detroit ultimately won, 6-2), and the fans in the sold-out stadium booed Gibson loudly. Gibson may have reinjured his wrist on May 12 and did not return to the starting lineup for the rest of the month (he pinch-ran twice). Back in the lineup on June 1, he started until June 11, the last game before the players’ strike. Gibson finished the strike-split season on a tear, raising his batting average to .328 (9 home runs, 40 RBIs) from a paltry .235 when play resumed on August 10. The Tigers were in the playoff hunt until the final series of the season, when they lost to the Milwaukee Brewers. Anderson made the team watch the Brewers celebrate and told them to “think about that in the offseason.” Despite his early-season travails, Gibson was honored as Tiger of the Year by the Detroit baseball writers.

Everyone, including Gibson, thought 1982 was going to be his year. But once again the injury jinx struck. He appeared in 69 games, missing time with injuries to his knee, calf, and wrist, as well as being mysteriously sidelined by what turned out to be an intestinal parasite. The year began with Gibson mired in an 8-for-50 slump in the first two weeks. He had a run-in with Anderson over being pulled in the seventh inning of a game for defensive purposes. Later in the season, Gibson was in the middle of a brawl with the Minnesota Twins in which his good friend Dave Rozema suffered a season-ending knee injury trying to karate-kick a Twins player. Gibson’s season ended in a pinch-running role on July 8 with a .278 average and 8 home runs, after he reinjured his wrist.

The 1983 season, during which Gibson turned 26 — an age at which observers expect continued improvement from promising players — proved to be his hardest. Anderson decided Gibson was too arrogant and egotistical and needed to improve his professionalism on and off the field. Talking to Tigers beat writers the previous autumn, Anderson had spoken about players needing to be polite and sign autographs, to appreciate the fans, and to be grateful for their position in life. Few doubted that his words were meant for Kirk Gibson. Sparky’s lessons began at the end of spring training when he announced that Chet Lemon would be the starting center fielder. On Opening Day, Sparky told Gibson that he would be platooned, batting only against right-handers. Additionally, Gibson would be primarily used as a designated hitter. Kirk was so angry he shut the door and backed Sparky into a corner. But Anderson held his ground, and after Gibson finished his rant, Anderson asked if he was done and told him to “open the door and get your ass outta here.”

Gibson had a streaky year. He started out in a slump, batting just .164 into mid-May. He had missed ten games when he had a bone chip removed from his knee. He then hit .319 for the next month and on June 14 crashed a 523–foot home run over the right-field roof at Tiger Stadium. In the same game his speed led him to try for an inside-the-park home run. In a strange play at the plate, the runner in front of him, Lou Whitaker, was tagged out by the Red Sox catcher, Rich Gedman. Gibson, a mere 20 feet behind Whitaker, crashed into the umpire, Larry Barnett. While signaling the out on Whitaker, Barnett apparently stepped in front of Gibson, who managed to knock the ball loose from catcher Gedman and was ruled safe. Peter Gammons wrote in a Sporting News article headlined “Most Exciting Player? Gibson”: “He also is as much fun to watch as any player in this league, whether hitting 523-foot home runs, racing out of control around the bases, or just plain running. Unlike some of the supposedly exciting base-running types, he is worth the price of admission every time he goes into motion.” The game brought Gibson’s average to .236, and he reached .253 by June 20. But then he seemed to lose his stroke, and his batting average skidded to .227 by season’s end, albeit with 15 home runs. He was mercilessly booed by the fans, and Anderson dropped him lower and lower in the batting order. By the end of the year, the manager’s message had gotten through. The world and the Tigers did not revolve around Kirk Gibson. Gibson had his detractors in the media as well. He could be arrogant and unpleasant; one writer described him as hostile and menacing. Years later, Gibson reflected on his struggles: “I lost my focus. I wasn’t a good player. I had poor work habits.”

Up to then, Gibson had usually spent his offseason hunting and fishing. He preferred the company of his hunting dogs to people. But after all the troubles with his manager, the media, and the fans in 1983, Gibson realized he had hit bottom and needed help. He contacted his agent, Doug Baldwin, who told Kirk he should try a place in Seattle called the Pacific Institute. He spent four days with an instructor named Frank Batenetti, who turned his life around. Gibson managed to overcome the negative mindset from the 1983 season and learned to imprint a positive image in his mind. He embarked on a strenuous workout program, much as he did before beginning his college football career.

The change in Gibson in spring training of 1984 was immediately apparent. He was clean-shaven and had cut his hair. He looked trimmer and sported a positive attitude. Gibson had refused to spend the winter playing ball and learning how to play first base. In 1983, he had told reporters that he wanted Anderson to “keep me out of right. I hate it out there.” But now, with his new attitude, he accepted playing that position. The Tigers decided he needed tutelage in right field and brought in Hall of Famer Al Kaline to work with him. Kaline and Gibson worked tirelessly on positioning and throwing. Gibson got additional support from pitching coach Roger Craig, who spent many hours hitting grounders and fly balls to Gibson and helping him reaffirm the positive attitude he learned from the Pacific Institute. Craig also went to bat on Gibson’s behalf with Anderson. He helped convince Sparky that Gibson should play every day. The Tigers expressed their faith in Gibson by trading promising young outfielder Glenn Wilson to the Philadelphia Phillies as part of a package that brought reliever Willie Hernandez to the Tigers.

The Tigers got off to a great start, going 35-5, and Gibson contributed several key hits. His regained confidence at the plate and in the field ensured that his name would be on the lineup card daily. He played in 149 games, becoming the team’s first “20-20” man, smashing 27 home runs and stealing 29 bases, to go with a .282 average and 91 RBIs. He set a team record with 17 game-winning RBIs. Craig noted the growth of Gibson as a leader in the clubhouse and called him a born winner who thrives on pressure. The Tigers won their division easily, finishing 15 games ahead of their closest competitor, the Toronto Blue Jays. Their opponent in the American League Championship Series was the Kansas City Royals. The Tigers cruised in Game One, winning 8-1. Gibson’s big contribution came on a defensive play he made on a line drive by George Brett with the bases loaded and two out in the third inning, and the Tigers clinging to a 2-0 lead. Detroit won Game Two 5-3 in 11 innings, with Gibson contributing a double and a home run, scoring twice and driving in two runs. The Tigers completed the sweep in Game Three, winning 1-0 behind the pitching of Milt Wilcox and Willie Hernandez. Gibson was named the MVP of the series.

The Tigers’ World Series opponent was the San Diego Padres, who had come back from two games down to beat the Chicago Cubs, three games to two. The Tigers won the opening game, 3-2, with Jack Morris pitching a complete game. Gibson was hitless but contributed a key play in the seventh inning when his throw helped cut down Kurt Bevacqua trying to stretch a leadoff double into a triple, keeping the bases empty and preserving Detroit’s one-run margin. He went 2-for-4 in Game Two with a stolen base, but Detroit’s early 3-0 lead did not hold up as the Padres rallied to win, 5-3. But Gibson was saving his best for last.

The Tigers won Game Three, 5-2, and Game Four, 4-2. Game Five was played at Tiger Stadium on a gray Sunday afternoon. Gibson slugged a two-run home run in the first inning to get the Tigers’ offense started. But the Padres showed signs of life when they rallied to tie the game, 3-3. Gibson led off the fifth inning with an infield single. He moved to second on a long fly ball and two third on two walks. With one out, pinch-hitter Rusty Kuntz hit a popup to shallow right field caught by the second baseman, Alan Wiggins. Gibson took everyone by surprise by tagging up and scoring on the play, giving the Tigers the lead. When Gibson came to bat in the eighth inning, he had runners on second and third with one out, with the Tigers again clinging to a one-run lead, 5-4. On the mound was his old nemesis, Goose Gossage. When Padres manager Dick Williams went to the mound, Sparky Anderson flashed four fingers at Gibson. He was indicating he thought the Padres would walk Gibson to set up a possible double play. But Gossage was convincing his manager that he could handle Gibson, as he had in the past. Gibson yelled to Sparky, “Ten bucks they pitch to me and I crank it.” The first pitch was a fastball off the plate. Gibson was sitting on the next fastball and launched it deep into the right-field bleachers for a three-run homer, and everyone knew the ballgame was over. The most famous image from the World Series was Gibson leaping, arms above his head in triumph, after he circled the bases. The Padres went out meekly in the ninth inning, and the Tigers were World Series champions.

The Tigers were the toast of the town, feted and celebrated throughout the offseason. Most pundits picked them to repeat in 1985. Gibson sought to keep his personal fire burning, posting an “I’m Ornery” sign over his locker in spring training. He went on to have perhaps his finest season as a Tiger, playing in 154 games, scoring 96 runs, knocking in 97 runs, stealing 30 bases, and hitting 37 doubles and 29 home runs, while finishing with a .287 batting average. But despite other noteworthy individual seasons, particularly by Whitaker, Lance Parrish, and Darrell Evans, the Tigers finished third in the AL East, 15 games in back of the Blue Jays.

Several events occurred after the 1985 season that significantly affected Gibson’s future. He married JoAnn Sklarski in December as part of a double wedding ceremony with teammate and best friend Dave Rozema, who married JoAnn’s sister Sandy. Gibson’s carefree bachelor days were over, and he would be focused on his family when considering future baseball prospects. Gibson was a free agent after the end of the 1985 season, and with the season he had, he was expecting a lot of suitors from the other teams. Surprisingly, teams that seemed interested earlier suddenly backed out of negotiations. This was later found by an arbitrator to be collusion on the part of the major-league teams. At the time, however, Gibson felt that he had little choice but to accept the Tigers’ offer. He called them from his honeymoon in New Zealand with one minute remaining before the deadline. The three-year, $4.1 million contract made Gibson the highest-paid Tiger.

Gibson got off to a hot start in 1986, hitting two home runs in a 4-for-4 day with five RBIs on Opening Day, April 7, as the Tigers beat the Red Sox, 6-5. On April 22, Gibson was hitting a robust .359 when the injury jinx struck again. Returning to first base on a pickoff play, he severely twisted his ankle and foot. He missed 33 games. The Tigers went from a game out of first to nine back. Despite playing in only 119 games in 1986, Gibson still managed to hit 28 home runs, drive in 86 runs, and steal 34 bases. He also set a major-league record by collecting game-winning hits in four consecutive games.

The 1987 season started ominously for Gibson when he tore a rib muscle during batting practice and began the season on the disabled list. When he finally returned to action on May 5, the Tigers were 9-15, and were 11 games out of first place. They went 89-49 the rest of the way in an exciting pennant race that came down to the final three-game series against the Toronto Blue Jays. A week earlier, the Tigers had seemed hopelessly out of contention after dropping three in a row to the Jays. But they came back to win the fourth game with Gibson blasting a game-tying home run in the ninth inning off closer Tom Henke, and knocked in the winning run in the 13th inning as the Tigers kept their slim hopes alive. Going into the final series in Detroit, the Tigers needed a sweep to win the pennant outright — and they got it. The Tigers went into the AL playoffs a big favorite over the Twins, but lost in five games. Gibson had another fine season despite the early injury, hitting batting .277, with 79 RBIs, 95 runs scored, 24 home runs, and 26 stolen bases. During the offseason, he set an altitude flying record for a Cessna 206, reaching a height of 25,200 feet. (During Gibson’s second term of service with the Tigers, he often flew a small plane from his home in upstate Lapeer to Detroit City Airport, then drove to Tiger Stadium for the game.)

Once again Gibson was on the verge of free agency. The Tigers tried to trade him to the Los Angeles Dodgers for Pedro Guerrero, but the deal fell through when the Dodgers learned Gibson was going to be declared a “second look” free agent due to an arbitrator’s collusion ruling against the owners. He continued to negotiate with the Tigers, but ended up signing a three-year, $4.5 million contract with the Dodgers. Gibson was stung when the Tigers new owner, Tom Monaghan, called him “a disgrace to the Tiger uniform with his half-beard, half-stubble.” Monaghan continued bashing Gibson on the radio, declaring that the Tigers would be better off without him.

Gibson quickly established his presence in the Dodgers’ clubhouse in 1988 spring training. His teammates played a prank on him that led to his storming off the field and demanding a team meeting to set things straight. He made it clear he was there to win a championship and he would do whatever it took to do so. Gibson led the Dodgers in home runs, runs scored, doubles, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage as the Dodgers won the National League West by seven games over the Cincinnati Reds. The championship series with the New York Mets went the full seven games. Gibson contributed a game-winning homer in the top of the 12th inning of Game Four that tied the series. The following day he hit a three-run homer in the fifth inning that put the Dodgers up 6-0 in a 7-4 victory. But Gibson injured his left knee stealing second base in the ninth inning after having been intentionally walked. He played in Game Six after receiving a cortisone shot, but the Mets won, forcing a deciding seventh game on October 12. Gibson got the Dodgers out to an early lead with a sacrifice fly in the first inning. In the second, Los Angeles scored five more runs to put the Mets in a deep hole. Gibson was again walked intentionally and injured his right knee sliding hard into second base. He tried to gut it out, but finally came out of the game in the fourth inning. The Dodgers went on to win the game easily, 6-0.

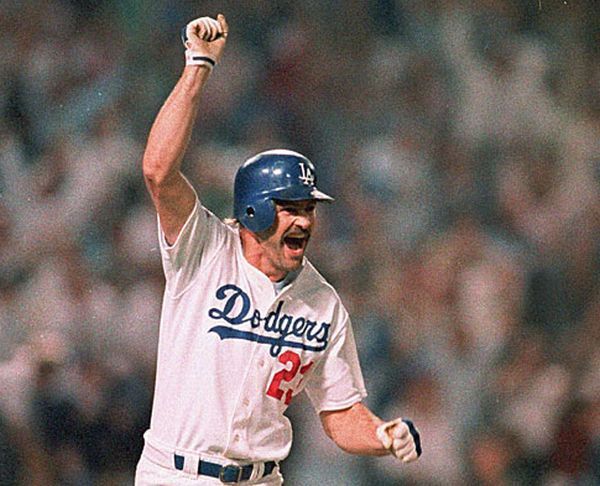

The World Series against the Oakland A’s was scheduled to begin three days later, on Saturday, October 15. The Dodgers’ medical team worked feverishly trying to get Gibson ready to play, but to no avail. When the Game One introductions took place, he was in the clubhouse with ice on both legs. The A’s rode a Jose Canseco grand slam to a 4-3 lead going into the ninth inning. Oakland’s star closer, Dennis Eckersley, easily retired the first two batters. When the inning started, Gibson had hobbled over to a batting tee and begun taking practice cuts. He told the clubhouse attendant to get the manager, Tommy Lasorda. Gibson told the manager he could pinch-hit. In the meantime, with two outs, Mike Davis, pinch-hitting for Alfredo Griffin, worked Eckersley for a walk. As Gibson climbed up the dugout steps onto the field, the Dodger Stadium crowd went crazy. Eckersley quickly got ahead of Gibson, 0-2 as he barely fouled off the first two pitches. Gibson managed to work the count full and stepped out of the box. The Dodgers’ advance scout, Mel Didier, had told Gibson that if he ever faced Eckersley with a full count, Eckersley was certain to throw a backdoor slider. And that’s the pitch Gibson drove into the right-field bleachers for the game-winning home run. He limped around the bases with his arm held high celebrating the shocking turn of events. (Broadcaster Jack Buck, famous for his “I can’t believe what I just saw” call of the homer, also mistakenly said the Tigers had won the ballgame.) The Dodgers had seized momentum from Oakland and went on to win the Series in five games. It was Gibson’s only appearance in the 1988 World Series.

The World Series against the Oakland A’s was scheduled to begin three days later, on Saturday, October 15. The Dodgers’ medical team worked feverishly trying to get Gibson ready to play, but to no avail. When the Game One introductions took place, he was in the clubhouse with ice on both legs. The A’s rode a Jose Canseco grand slam to a 4-3 lead going into the ninth inning. Oakland’s star closer, Dennis Eckersley, easily retired the first two batters. When the inning started, Gibson had hobbled over to a batting tee and begun taking practice cuts. He told the clubhouse attendant to get the manager, Tommy Lasorda. Gibson told the manager he could pinch-hit. In the meantime, with two outs, Mike Davis, pinch-hitting for Alfredo Griffin, worked Eckersley for a walk. As Gibson climbed up the dugout steps onto the field, the Dodger Stadium crowd went crazy. Eckersley quickly got ahead of Gibson, 0-2 as he barely fouled off the first two pitches. Gibson managed to work the count full and stepped out of the box. The Dodgers’ advance scout, Mel Didier, had told Gibson that if he ever faced Eckersley with a full count, Eckersley was certain to throw a backdoor slider. And that’s the pitch Gibson drove into the right-field bleachers for the game-winning home run. He limped around the bases with his arm held high celebrating the shocking turn of events. (Broadcaster Jack Buck, famous for his “I can’t believe what I just saw” call of the homer, also mistakenly said the Tigers had won the ballgame.) The Dodgers had seized momentum from Oakland and went on to win the Series in five games. It was Gibson’s only appearance in the 1988 World Series.

Gibson had a thoroughly enjoyable offseason. He was named the National League Most Valuable Player for 1988. (Gibson was the first, and through 2008 the only MVP winner to never appear in an All-Star game. He had been selected twice, in 1985 and 1988, but declined to attend.) Gibson even got an apologetic phone call from Tom Monaghan. The call included an invitation to lunch with his former owner, which Gibson declined. But when spring 1989 rolled around, Kirk’s hamstring problems continued to plague him. He played in only 71 games, finishing his season in Pittsburgh on July 22 before deciding to undergo exploratory surgery. Doctors found that the hamstring had been torn, and after they cleaned it up, Gibson began a long rehab. He missed almost a full year, returning to play against Cincinnati in Los Angeles on June 2, 1990. Those two partial seasons were disappointing ones for the Dodgers, despite Gibson’s 26 steals in 89 games in 1990, and Los Angeles made no effort to re-sign him after the 1990 season. He wanted to return to the American League and agreed to a two-year contract with the Kansas City Royals. Gibson got off to a good start in 1991, hitting six home runs in April. But manager John Wathan was fired after 37 games and replaced by Hal McRae. Gibson and McRae had had a run-in back in Gibson’s rookie year, and Gibson believed McRae still held a grudge. Indeed, McRae told Gibson in spring training the following year that he had no chance of winning a starting job. On March 10, 1992, Gibson was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates for pitcher Neal Heaton. The good news for Gibson was that he was reuniting with his first manager, Jim Leyland. But Gibson could never get untracked, and after hitting just .196 in 16 games with the Pirates, he was given his unconditional release on May 5. Gibson, 35 years old, returned home to Michigan and spent the summer with his family.

By now, the Tigers had a new owner, Mike Ilitch, who had always loved the way Gibson played the game, and wanted to bring him back. Gibson signed a one-year deal for $500,000 for the 1993 season. He had a good season, contributing 13 home runs and 62 RBIs to a team that improved by 10 games in the win colSociety for American Baseball Researchumn. The 1994 season was shortened by the strike, and the Tigers sagged to last place in the AL East, but just one game behind fourth-place Boston and two behind third-place Toronto. Despite the Tigers’ disappointing performance, Gibson hit .276, hammered 23 home runs, and drove in 72 runs in the short, 115-game season, and was named Tiger of the Year by the Detroit sportswriters.

Gibson and the Tigers reached a last-minute agreement for the 1995 season. But, now 38, he found himself lacking the fire and drive that typified his playing career. When the Tigers conceded that their season was over by trading two of their top pitchers, starter David Wells to Cincinnati on July 31 and closer Mike Henneman to Houston ten days later, Gibson decided it was time to retire. He played his final game on August 10, 1995. In 1,635 major-league games over 17 seasons, he batted .268 with 255 home runs, 284 stolen bases, 985 runs scored, and 870 runs batted in.

After his baseball career ended, Gibson ran an investment firm. He enjoyed spending time with his wife, JoAnn, and his four children, Kevin, Kirk, Cameron, and Colleen. For a brief time he served as a color analyst for Tigers games on Fox Sports Net Detroit, and as a co-host of a popular sports talk radio show. But the lure of the game was too much, and Gibson returned to the Tigers as a bench coach beside his friend and onetime teammate Alan Trammell from 2003 through 2005. After Trammell was fired, Gibson interviewed for a couple of managerial posts and finally caught on as a bench coach for the Arizona Diamondbacks — then managed by another onetime Tigers teammate, Bob Melvin — in 2007, remaining with the team after Melvin was fired early in the 2009 season. But after Melvin’s successor, A.J. Hinch, was fired, Gibson was given the interim manager’s position July 2, 2010.

Gibson was an enigmatic baseball player. His early promise was never fulfilled, and he was considered a below-average outfielder with a weak throwing arm. But he will always be remembered for the intangibles he brought to his teams. Sparky Anderson once wrote of Gibson, “I’ve never seen a player change his direction so completely. His personality, his drive, his dedication are unsurpassed. He knew how to make things happen. Gibby gets the highest rating as a player from me.”

Sources

Publications

Anderson, Sparky. Bless You Boys: Diary of the 1984 Detroit Tigers’ Season. Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1984.

Cantor, George. Wire to Wire: Inside the 1984 Detroit Tigers Championship Season. Chicago: Triumph Books, 2004.

Craig, Roger. Inside Pitch: Roger Craig’s ’84 Tigers Journal. Grand Rapids, Mich.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1984.

Stanton, Tom. The Detroit Tigers Reader. Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Zaret, Eli. ’84: The Last of the Great Tigers: Untold Stories From an Amazing Season. South Boardman, Mich.: Crofton Creek Press, 2004.

Articles

Fimrite, Ron. “The Tigers Roar to the Pennant.” Sports Illustrated, October 15, 1984.

Fimrite, Ron. “The Happy Hunter.” Sports Illustrated, December 10, 1984.

Gage, Tom. “Tigers All Set for Gibson Payoff.” The Sporting News, December 8, 1979: 52.

Gage, Tom. “Old Injury Hex Confronts Gibson.” The Sporting News, February 28, 1983: 35.

Gage, Tom. “Lemon and Gibson to Duel in Center.” The Sporting News, March 14, 1983: 28.

Gage, Tom. “Sparky Wants Lemon for CF.” The Sporting News, April 11, 1983: 36.

Gage, Tom. “Right Is All Wrong for Injured Gibson.” The Sporting News, April 25, 1983: 25.

Gage, Tom. “A Titanic Shot By Kirk Gibson.” The Sporting News, June 27, 1983: 20.

Gage, Tom. “Sparky Fidgets as Kirk Flounders.” The Sporting News, August 8, 1983: 12.

Gage, Tom. “Sparky Hasn’t Given Up on Gibson.” The Sporting News, February 6, 1984: 43.

Gage, Tom. “Signing Gibson May Be a Problem.” The Sporting News, December 10, 1984: 52.

Gage, Tom. “Gibson Won’t Gamble.” The Sporting News, January 20, 1986: 43.

Gammons, Peter. “Most Exciting Player? Gibson.” The Sporting News, June 27, 1983: 27.

Hawkins, Jim. “Instant-Star Gibson Falls Into Tigers’ Net.” The Sporting News, July 1, 1978: 15, 40.

Hawkins, Jim. “Bengals Glance the Other Way as Gibson Runs Pass Patterns.” The Sporting News, December 2, 1978: 56.

Kurkjian, Tim. “Go-Go Gibby.” Sports Illustrated, May 17, 1993.

Young, Dick. “Showboating by Ump Causes Foul-Up.” The Sporting News, June 27, 1983: 4.

Websites

http://www.baseballlibrary.com

http://www.espn.com

http://www.retrosheet.org

http://www.thebaseballcube.com

http://www.thebaseballpage.com

http://www.wikipedia.com

Full Name

Kirk Harold Gibson

Born

May 28, 1957 at Pontiac, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.