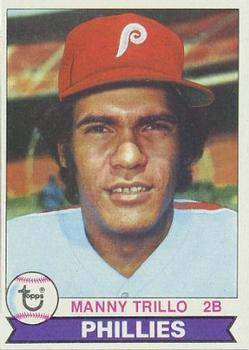

Manny Trillo

Outstanding defense and strong character can be a short description for Manny Trillo’s career. He was a slick-fielding second baseman who shined with a legendary Philadelphia Phillies team and played a huge part in the first title in almost 100 years of misery in one of the fieriest sports markets in the world.

Outstanding defense and strong character can be a short description for Manny Trillo’s career. He was a slick-fielding second baseman who shined with a legendary Philadelphia Phillies team and played a huge part in the first title in almost 100 years of misery in one of the fieriest sports markets in the world.

Trillo is always remembered by fans for his distinctive fielding. A not untypical description of Trillo after getting the ball: “Seemingly stopping and reading the NL president’s signature on the ball before firing it sidearm.”1

But the path to an All-Star career that started with the power machine of the Oakland Athletics was not an easy one. The story began in the rural town of Caripito in northeastern Venezuela, where Jesús Manuel Trillo was born to Trina Trillo and Ismael Marcano on December 25, 1950.

“My parents were separated since the day I was born and I always lived with my mother,” Trillo recalled in 2001. “My mother took care of me and my siblings Ismael, Eneida, and Zunilda. She was the mother and a father figure for us and she took good care of us. I was never too close to my father, we used to see him once in a while but we were never really close.”2

Trillo’s father was a worker in the booming oil industry, which widely promoted little league and other baseball programs. Young Jesús played on the teams and tournaments sponsored by these programs. Jesús grew up in Quiriquire, a small town in the oilfields, and during his middle-school years, his physical education professor, Rómulo Ortiz, took him under his wing, including him on organized teams and taking him to play local tournaments and competitions. Jesús saw Rómulo as a father figure who passed on to the boy his love for the game. Ortiz used to call him Indio (Indian), making fun of the shy character and personality of his pupil. This nickname stuck with Manny for life.

As a youngster Jesús primarily played shortstop, where he developed quick hands and speed. He admired the two All-Star Venezuelan shortstops in the majors, Chico Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio, both local sports heroes. But one day the catcher for his team was injured and he was sent to play behind the plate. Jesús cried the whole game since he was afraid a foul ball was going to hit him. It didn’t happen, and the joy and experience of calling and receiving pitches captured his attention. After that game, he became a catcher.

Jesús became passionate for the game, even skipping classes to go practice as a teenager. By the age of 14, he was determined to become a professional baseball player. His parents supported his diamond dreams.

Ortiz contacted Pompeyo Davalillo, who had recently retired as a player after a cup of coffee with the Washington Senators in 1953, and worked as a coach for Leones del Caracas of the Venezuelan League and a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies. In October 1965 Ortiz and his protégé traveled 10 hours Caracas to see him. Davalillo saw something special in him. He agreed to work with the youngster and, with his mother’s permission, kept him in Caracas to train.

Trillo spent two years traveling from Caracas to Maturin, where he studied at Escuela Técnica Industrial. He participated in a tryout after an exhibition game in 1967 in Caracas between the Oakland A’s and the Minnesota Twins. In January 1968 the Phillies signed him to a contract, and a few days later the 17-year-old flew to Clearwater, Florida, where the Phillies trained.

Facing a new language, a new culture and new challenges and being alone for the first time was ahead for a teenager from a rural oil town in Venezuela. “It was one of the hardest moments of my life,” Trillo said. “I cried a lot and for and for many months. Leaving behind my mother was very hard but it was all worthy to try to achieve my dream of becoming a baseball player. And I wanted to play in the major leagues. I was determined.”3

Jesús Manuel Marcano, his legal name in Venezuela, became Manny Trillo, a common mistake when processing legal paperwork between the US and Latin countries, where last names are usually confused with maiden names. “They started calling me Manny as a short for Manuel and they put my last name as Trillo, instead of Marcano. However that never bothered me since it was my mother’s last name and I was proud of carrying her last name on my back. Although in Venezuela they kept using both of my surnames for the records, so it became Manny Trillo for the United States and Jesús Marcano Trillo in my country, even only Marcano Trillo. It was fine in any way for me.”4

Trillo went to the Phillies camp as a catcher, but Dallas Green, who had just retired as a player and was to manage Huron (South Dakota) in the short-season Northern League, saw him fielding groundballs and realized his potential as an infielder. Trillo was assigned to Huron as a catcher, but after a few games Green decided to try him at shortstop and third base. “There was no way I was going to put this fragile, skinny kid behind the plate,” wrote Green in his memoirs. “I found time to give Manny a little extra attention. He was one of the few Latin kids on the team. I could only imagine how difficult was for Manny at that time. In the lower minor leagues you make peanuts. I slipped Manny a few bucks here and there, because I knew he had nothing.”5

Trillo played only 35 games at Huron, hitting .261 and performing well at shortstop. After the season he returned to Venezuela to play with Caracas and was already seen as an infielder.

Trillo spent the 1969 season with Spartanburg (South Carolina) of the Western Carolinas League, where he played mostly in the infield but put in some time behind the plate for the last time in his career. He improved with the bat, hitting .280 with 26 RBIs in 83 games, but seemed to attract little attention from the Phillies. But he caught the attention of Oakland owner Charlie Finley, and the Athletics drafted him in the minor-league phase of the 1969 Rule 5 draft. The A’s assigned the 19-year-old to Double-A Birmingham (Southern League), where he played shortstop, second base, and third base in 1970 and shortstop and third base in 1971.

Trillo was viewed as a backup infielder, but with more playing time, his offensive performance improved consistently. In 1971 he batted .280 with 5 home runs and 44 RBIs. In the winter league he hit .291 in 35 games for Caracas.

In 1972 Trillo was assigned to Triple-A Iowa, where manager Sherm Lollar played him at shortstop, second, and third, and he batted a strong .301 in 133 games with 9 home runs. After the season, Trillo rejoined Leones of Caracas and played all 61 games of winter baseball as a third baseman, hitting .240 with 5 home runs. He played a huge role in helping his team to the league championship.

It was Trillo’s first taste of championship, and he was also in a world championship organization, as the A’s beat the Reds in the World Series while he was playing in his home country. After winning the Venezuelan championship, Leones moved to the Caribbean Series (played in Caracas) and lost to Tigres del Licey from the Dominican Republic. For Trillo it was exciting to understand winning in baseball.

The world champion Athletics had Bert Campaneris at shortstop and Sal Bando at third base; so Trillo hoped to make the team as a second baseman. He was assigned to Triple-A Tucson.

“When we were in Triple A in 1973, my good friends Gonzalo Marquez and José Morales told me that the only chance I had to reach the majors with the A’s was in second base,” Trillo said in 2001. “So every day before each game in Tucson we went early to the park in our own time just to practice. They used to practice a lot of double plays with me and help me a lot with grounders. We did that for one or two hours each day before the team practice. Sherm Lollar saw our hard work and that I was focusing more on becoming a better second baseman and he gave me the chance to play that season every day on my new position.”6

In 130 games, Trillo made 19 errors but gained confidence on the field and hit .312 with eight home runs. He led the team with 78 RBIs. With such a solid performance, Charlie Finley saw his promising 22-year-old Triple-A second baseman as part of the team’s future. On June 28, Trillo was called up to make his major-league debut, against Kansas City.

“I remember clearly my first at-bat since I hit the ball to right field and I drove in what eventually was our winning run, he recalled.”7 (Two batters later, Trillo was picked off by Kansas City pitcher Steve Busby, but another Oakland run scored in the process.) “Wearing for the first time a major-league uniform was the best sensation I had in my life. I had achieved my goal.”8

Trillo played 17 games with Oakland and was 3-for-12. The A’s advanced to the American League Championship Series, meeting the Baltimore Orioles for the second year in a row. Trillo was supposed to be on the roster but almost didn’t. In error, his name was left off the roster submitted to major-league baseball. Fortunately for Trillo, the Orioles allowed him to be added to the roster, along with Allan Lewis, substituting for the injured Billy North. In the end, Trillo didn’t see any action in the ALCS, which the A’s won in five games.

The story took a turn when the A’s advanced to the World Series and had to petition the New York Mets for the roster changes. The Mets allowed Lewis for North but denied the addition of Trillo. (Before Game One an irate Finley had the PA announcer at the Oakland Coliseum tell fans to scratch Trillo from their lineup cards because the Mets had not allowed the roster adjustment, an action for which he was fined by the commissioner’s office.)

Trillo started the 1974 season with the A’s but was sent to back to Tucson after hitting .100 during the first month. He was recalled in September. He was included on the postseason roster and scored a run as pinch-runner in the ALCS against the Orioles, but did not play in the World Series, which the A’s won over the Los Angeles Dodgers, their third title in a row.

Six days after the Series ended, Trillo was traded to the Chicago Cubs along with relievers Darold Knowles and Bob Locker for outfielder and future Hall of Famer Billy Williams.

Trillo was designated the starting second baseman, and never returned to the minors. In his first season with the Cubs, 1975, he hit .248 with 7 homers and 70 RBIs, but his defense was rough (29 errors). “My teammates used to make fun of me in Chicago saying that for me errors were like a vitamin … one a day,” he joked. “But I worked hard on the position and little by little the errors were disappearing from my game.”9 Trillo was third in votes for the National League Rookie of the Year.

Trillo spent four seasons as the Cubs’ primary second baseman. In 1977 he made the National League All-Star squad as a backup to Joe Morgan. In February 1979 he was traded to his original club, the Phillies, in an eight-player deal. Philadelphia was seeking to upgrade its infield. It became one of the best trades the Phillies ever made. Under manager Dallas Green, Trillo shone. His improvement with the glove was evident; he made fewer errors, and showed flash and elegance in his defense. He won the first of his three Gold Gloves.

Trillo’s trademark style was to catch a groundball and take a brief moment to look at the ball on his hand before making the throw to first base. “Some players used to tell me: Get rid of that ball faster! But I was just taking my time and watched the ball. Some people thought I was cocky, but no, maybe I was too serious on my job. I just like to do things right.”10

After the 1979 season Trillo went back to Venezuela, where he had become a big star with Leones del Caracas. He hit .306 in 30 games and helped Caracas to win its third title in eight seasons. Trillo remained with the team to play the Caribbean Series in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, which was won by a Dominican team, Tigres del Licey.

In 1980 the Phillies under Green won 91 games and Trillo was on center stage, batting.292 with 7 home runs and 43 RBIs and winning the NL Silver Slugger award at his position. His momentum rolled over to the NLCS, in which the Phillies defeated the Houston Astros in five games. and Trillo (8-for-21, .381, four RBIs) was declared the NLCS MVP after a key RBI double in Game Four and a two-run triple in the clinching Game Five.

The Phillies advanced to the World Series against the Kansas City Royals. Trillo hit only .217 in the Series, he helped win Game Five with a great relay throw that kept the Royals from scoring a run, and got a ninth-inning infield hit that drove in the game’s winning run. Two nights later, in Game Six, the Phillies won their first World Series title.

When Trillo returned to Venezuela, he stepped into controversy, fighting with Leones over its salary offer. A league-appointed arbitrator couldn’t settle the dispute and Trillo demanded a trade.11 He was traded to Aguilas del Zulia, probably the biggest and most impactful trade in the history of the Venezuelan Winter League. Trillo became a leader of the team, which reached the playoff finals in 1981 and 1982.

The trade had a big impact on Trillo’s career. “It’s was painful for me to leave Caracas, but they received me so well in Zulia and they made me feel part of the team so fast that it became my new home,” he said. “Also my wife was from Maracaibo and it made perfect sense for the family.”12

In 1982 with the Phillies Trillo set a major-league record with 479 consecutive errorless fielding chances as a second baseman. When he finally made an error, it was on a high bouncer by Bill Buckner over the pitcher’s head. “I thought the ball was going to hit the ground making it routine for me to catch it, but it hit the turf and the bound was higher and hit my elbow. I thought they were going to call it a hit, but my defensive game got people in Philadelphia used to seeing a hard play as an easy one and that tricked me that day.” The official scorer took almost three minutes to make a decision and confirmed the error. The game stopped and the crowd gave Manny a standing ovation for over five minutes. “That was very special for me. I said, ‘Wow! I made an error and people cheer at you!’”13

Trillo won his second consecutive Gold Glove, the third of his career. He was the starting second baseman for the National League in his third All-Star Game.

But happy times in Philadelphia came to an end. Baseball was changing and he understood the business. During his time with the Phillies his agent was David Landfield. In December 1982, while playing with Zulia, Trillo was traded to the Cleveland Indians along with George Vukovich, Jerry Willard, Julio Franco, and Jay Baller for highly-touted prospect Von Hayes. It was one of the worst trades in the Phillies’ history, but trading two potential free agents to get a long-term player seemed to make perfect sense.

After the trade Trillo’s former wife, Maria Elena, took over as his agent. She became the only female agent in the business, negotiating for her husband. For the Indians he hit .270 in the first half of the 1983 season and made the All-Star Game as the starter at second base.

By August, the Montreal Expos were looking for a solid infielder and they traded minor leaguer Don Carter for Trillo to help in a pennant chase they eventually lost. After the season Trillo became a free agent and signed with the San Francisco Giants. But his offense started to decline and after being used to playing with competitive clubs, he felt less motivation with the last-place Giants, hitting only .238 in 223 games over two seasons and making 18 errors.

In the meantime, Dallas Green had become the general manager of the Chicago Cubs; he needed infield backup, and acquired Trillo in December 1985 for infielder Dave Owen.

“As soon as I came back to Chicago Dallas told me to be ready to play all four infield positions,” Trillo said. “It will be hard, but I’m 35. What the heck. The time comes for every ballplayer. I`m happy to be back, and I hope this will be my last stop. I only have one space left on my cap rack back home.”14

Trillo became a mentor for younger Cubs players like Ryne Sandberg and Shawon Dunston. He was also a liaison between the Cubs and Zulia in Venezuela. The organizations had an unofficial agreement to exchange players that helped the Cubs develop prospects in winter ball. Trillo’s relationship with the Venezuelan team grew stronger after he was activated for the 1984 Caribbean Series in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in which Zulia won its first international title.

Trillo played three seasons in his second stint with the Cubs. He was a solid backup, hitting .296 in 1986.294 with a career-high eight homers in 1987 while playing all the positions on the infield. He was a fan favorite and on his at-bats bleacher fans used to chant: “One-O!, Two-O!, Trillo!”15

For the 1987-88 winter ball season, Trillo returned to Zulia, this time with double duty as a player-manager. He played his last 33 games as an active player in winter ball, hitting .270 while managing the team to a record of 23-37. “I felt I could play a couple more seasons in Venezuela, but I thought it was time to give back to baseball,” Trillo said. “I enjoyed more the coaching side than being a manager and after that experience I asked the team to allow me to continue as a coach.” Zulia agreed and in 1988 Trillo became a full-time coach.

Trillo was released by the Cubs after the 1988 season but he got an invitation from the Cincinnati Reds to be a backup infielder. After playing in 17 games during the first two months of the season, he was released. At the age of 38, “I was ready to continue as an instructor,” he said.16

Trillo’s fielding elegance and clutch hitting were his trademarks. He played for seven teams in his 17-year major-league career, with 1,518 games as a second baseman. As of 2014 he had the best fielding percentage of any Phillies second basemen,.994 in 1982, with only five errors in 149 games.

Trillo’s passion for teaching baseball and working in the minor leagues took him to work as a minor-league coach for the Cubs, Phillies, Brewers, Yankees, and White Sox. Ozzie Guillen, the White Sox manager, took him to the 2005 World Series as a guest coach.

In Venezuela Trillo continued to work with Aguilas del Zulia as a coach and special adviser. In his 19 seasons in the Venezuelan league he batted.277 with 29 home runs and 325 RBIs. In 2007 he was voted into the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2012 Trillo was voted into the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame. He attended the induction ceremony in La Romana, Dominican Republic, joining inductees Tony Oliva, Bernie Williams, and Tony Peña among other Latin greats.

In 2014 Trillo had homes in Orlando, Florida, and Maracaibo, Venezuela. He enjoyed spending time with his family and playing golf. In September, Aguilas del Zulia opens its training camp, he was there. “As long as I can and I’m capable, I’ll be wearing the baseball uniform on the field,” he said. “I enjoy being in the clubhouse, being around the guys and helping them to develop skills. … I am proud of what I did, I was serious about how I handled myself and I always respected the game and that is the biggest legacy of my career.”17

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Purapelota.com, Retrosheet.org, YouTube.com, and the following:

Epstein, Dan, Big Hair and Plastic Grass: A Funky Ride through Baseball and America in the Swinging ’70s (New York: Macmillan, 2012).

Green, Michael G., and Roger D. Launius, Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball’s Super Showman (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2010).

Westcott, Rich, Tales From the Phillies Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing LLC, 2006).

Westcott, Rich, Veterans Stadium: Field of Memories (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005).

Chass, Murray, “Maria Trillo Acts in Family Interest,” New York Times, November 11, 1983.

Lomartire, Paul, “Trillo Takes Heart Along, Leaves Gloom In S.F.,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1986.

McNesby, Mike, “Hard to Believe!” Lulu.com. 2009.

Mitchell, Fred, “For Dunston, a Season Of Commitment,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1986.

Megdal, Howard, “Jack of All Trades: Manny Trillo,” MLBRumors.com, 2010.

Diario Líder, Caracas, Venezuela, archives.

Diario La Verdad, Maracaibo, Venezuela, archives.

Landino, Leonte, personal interviews with Jesús Marcano Trillo in Maracaibo, Venezuela, November 18, 2012, and November 17, 2013; in La Romana, Dominican Republic, February 12, 2012; and in Bristol, Connecticut. March 28, 2014.

Notes

1 Al Yellon, Kasey Ignarski, and Matthew Silverman, Cubs by the Numbers: A Complete Team History of the Chicago Cubs by Uniform Number (New York: Skyhorse Publishing Inc. 2009), 120.

2 Leonte Landino, ¡Aguilas … A la Carga! Episode 79 (Tripleplay Sports Productions, Maracaibo, Venezuela, December 30, 2001.)

3 Augusto Cárdenas, “Un Indio con corazón zuliano,” Diario Panorama, Maracaibo, Venezuela, December 9, 2009.

4 Águilas a La Carga!, 79.

5 Dallas Green and Allan Maimon, The Mouth That Roared: My Six Outspoken Decades in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2013), 52.

6 Águilas A La Carga!, 79.

7 Augusto Cárdenas, Diario Panorama.

8 Ignacio Serrano, “Manny Trillo repasa las anécdotas de su carrera,” Diario El Nacional, Caracas, Venezuela, December 9, 2013.

9 Augusto Cárdenas, Diario Panorama.

10 Ignacio Serrano.

11 Ignacio Serrano.

12 Águilas a La Carga!, 79.

13 Augusto Cárdenas, Diario Panorama.

14 Bob Verdi, “Trillo Happy 2d Time Around,” Chicago Tribune. March 6, 1986.

15 Yellon, Ignarski, and Silverman, 52.

16 Leonte Landino interview with Manny Trillo, Maracaibo, Venezuela, 2012.

17 Águilas a La Carga!, 79.

Full Name

Jesus Manuel Marcano Trillo

Born

December 25, 1950 at Caripito, Monagas (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.