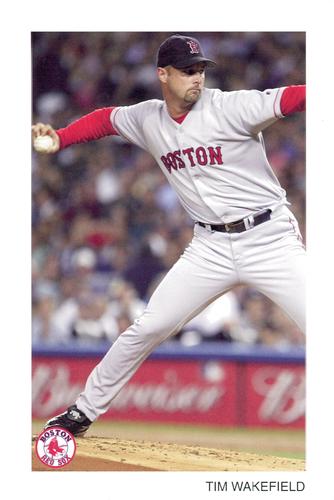

Tim Wakefield

Unfortunately, Tim Wakefield just ran out of time. The knuckleballer spent 17 seasons with the Boston Red Sox, recording 186 of his 200 career victories with the franchise – just six short of the team record held by Cy Young and Roger Clemens. He was also a member of two World Series champions, including the memorable 2004 team that ended an 86-year drought. Wakefield pitched until he was 45 years old, an age at which various “butterfly” specialists have remained productive. Wakefield might have tried to hook on with another team, but he said, “I never wanted to pitch for another team.”1

Unfortunately, Tim Wakefield just ran out of time. The knuckleballer spent 17 seasons with the Boston Red Sox, recording 186 of his 200 career victories with the franchise – just six short of the team record held by Cy Young and Roger Clemens. He was also a member of two World Series champions, including the memorable 2004 team that ended an 86-year drought. Wakefield pitched until he was 45 years old, an age at which various “butterfly” specialists have remained productive. Wakefield might have tried to hook on with another team, but he said, “I never wanted to pitch for another team.”1

Just over a decade after his retirement from the Red Sox, he died from brain cancer at 57 years old.

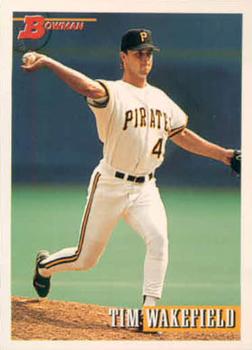

It’s not as though Wakefield was ever shooting for the Red Sox mark in the first place. In fact, he wasn’t even a pitcher to begin with. When he started his career in the Pittsburgh Pirates organization, he was an infielder.

Timothy Stephen Wakefield was born in Melbourne, Florida on August 2, 1966. He grew up in Melbourne and attended the public schools there, graduating from Eau Gallie High School in Melbourne.

His father, Steve, actually taught him the knuckleball early, at age 7 or 8. Steve was an active softball player who worked the morning shift (3 A.M. – 11 A.M.) at the Harris Corporation, an electronics company for which he designed circuits. Steve’s wife, Judy, had one other child, a daughter named Kelly. In time, Judy Wakefield also worked for Harris as a purchaser and professional assistant.2

Steve started throwing a knuckler to his son. “I robbed my son of a lot of things because I was so dedicated to softball,” he said. “So if he asked me to go out in the yard and play catch, I always said yes. But then he’d want to play and play and play, so I started throwing knuckleballs at him. He didn’t like it. Eventually, he’s say, ‘OK, I’ve had enough.’”3 So Tim learned early on how confounding the knuckleball could be, difficult to catch and difficult to hit. But, he admitted later, he hadn’t seen it as a serious tool. It was more like a “magic trick or a party stunt.”4

Tim went through T-ball and Little League, and as a Floridian, he could play baseball every day. The Atlanta Braves were his favorite team and Dale Murphy his favorite player. Tim won a baseball scholarship to Brevard Community College, but the other players were so good he quit the team before he ever got into a game. Head coach Les Hall of the Florida Institute of Technology saw potential in him and recruited him. Wakefield played first base for Florida Tech and did well enough, hitting 22 homers in one season, that in June 1988 he was selected by the Pittsburgh Pirates in the eighth round of the draft. He signed for a bonus of $15,000 and the commitment by the Pirates to pay for the remainder of his college tuition when he went back to school.

The Pirates placed Wakefield with their Watertown (New York) affiliate in the New York-Penn League. He played first base, appearing in 54 games. In 192 plate appearances, he managed only a .189 batting average with three homers and 20 RBIs, and he struck out 57 times. He was overmatched, but he showed good enough plate discipline to draw 25 walks, bumping up on his on-base percentage to .328.

In 1989, he played for two teams – a few games for the Augusta Pirates in the South Atlantic League, a Class A team, and then for the Welland (Ontario) Pirates back in the NYPL. His manager in extended spring training, Woody Huyke, had seen him fooling around with the knuckleball while playing catch with a teammate and saw how difficult it was to catch. At Welland, Wakefield was told to bring out the knuckler and he split his time between the infield and pitching (in 18 games). He won one and lost one and recorded a 3.40 ERA, and was sent to Instructional League in the fall. He knew he wasn’t going to make it as a hitter, so developing the unusual pitch seemed his only possible road – however unlikely it might be – to making the major leagues. Wakefield wasn’t thrilled about it, though, saying, “When they put an infielder on the mound, it’s like they’re putting you out to pasture. They’re saying you don’t have what it takes to get to the big leagues.”5

In 1990, his first season playing exclusively as a pitcher, his ERA was 4.73, and his record for the last-place Salem (Virginia) Buccaneers was 10-14 (hey had the worst record in the Carolina League.) In 1991, the Pirates advanced him to Double-A ball, pitching in Raleigh for the Carolina Mudcats in the Southern League. He had a very good year, 15-8 with a 2.90 ERA in 25 starts. He pitched in one game for Triple-A Buffalo and lost it.

In 1992, halfway through the season, Wakefield was called up to the major leagues. He’d been 10-3 (3.06) with Buffalo. The Pirates were truly in need of pitching.

He made his debut on July 31, 1992 for manager Jim Leyland. The Pirates couldn’t have hoped for a much better start, a complete-game win at Three Rivers Stadium against the visiting St. Louis Cardinals. He allowed six hits and walked five, but he struck out 10. Although he allowed two runs, neither of them was earned. It was a close 3-2 victory. “Really, I wasn’t nervous except for the first pitch,” he told reporters afterward. “I just stepped off the mound and looked around and saw Andy Van Slyke in center and Barry Bonds in left and Chico Lind at second…that always makes a pitcher feel better.”6

Wakefield’s next three starts were superb, too. Over his first four starts, he allowed just five earned runs and he was 3-0 with a 1.32 ERA. He lost one, 6-5 to the Giants in San Francisco, but didn’t give up more than three runs a game for the rest of the season, finishing 8-1 with a 2.15 ERA. In 92 innings, he’d given up only 76 base hits. Knuckleballers are rare. When Wakefield matched up against the Dodgers’ Tom Candiotti on August 26, it was the first time National League knuckleball pitchers had met since September 13, 1982 (when Phil Niekro faced his brother Joe).7 Wakefield threw a six-hit, 2-0 shutout.

Despite the late start, he came in third in Rookie of the Year voting – which was done before the postseason, in which Wakefield continued to shine. The Pirates made it to the National League Championship Series and Pirates GM Ted Simmons said his rotation was going to be “Doug Drabek, Danny Jackson, and the Miracle. That’s what Timmy has been for us since he came up.”8 Wakefield had two decisions, both complete-game wins, in Games Three (3-2) and Six (13-4). The Braves beat the Pirates in Game Seven. Wakefield’s postseason ERA was 3.00.

Despite the late start, he came in third in Rookie of the Year voting – which was done before the postseason, in which Wakefield continued to shine. The Pirates made it to the National League Championship Series and Pirates GM Ted Simmons said his rotation was going to be “Doug Drabek, Danny Jackson, and the Miracle. That’s what Timmy has been for us since he came up.”8 Wakefield had two decisions, both complete-game wins, in Games Three (3-2) and Six (13-4). The Braves beat the Pirates in Game Seven. Wakefield’s postseason ERA was 3.00.

The magical first year was followed by a disappointing 1993 season. Wakefield was given the honor of being the Opening Day pitcher, and won the game, but he walked nine batters. He was 6-11 with a 5.61 ERA with the Pirates, “a model of inconsistency – looking sharp in one outing and struggling in the next.”9

That inconsistency reflected the unpredictability of the pitch he threw. A couple of years later, Wakefield said, “I have no idea where it’s going, the hitter doesn’t know where it’s going, and the catcher doesn’t know where it’s going. I just try to throw it down the middle of the plate.”10 At one point, Wakefield was sent down two levels in midseason, back to Raleigh and the Double-A Mudcats for a couple of months. He put a good face on it, choosing not to take it as a demotion, but as something akin to a “rehabilitation assignment.”11 Even in Double A, however, he was 3-5 with a 6.99 ERA.

And in 1994, back in Buffalo at Triple A for the full year, he struggled even more; his ERA was 5.84 with a 5-15 record. It was mystifying at the time, but in some senses his performance simply reflected the most unpredictable to pitches: one really never knew when it would be “on” or “off.” Phil Niekro, the masterful knuckleball pitcher who made it to the Hall of Fame, said, “Tim was so successful early, and then he just lost it. That’s when it becomes tough mentally to throw a pitch everybody knows is coming. I’ve told him that he’s got to keep learning, he’s got to eat, sleep, walk, and talk the knuckleball until it floats in his bloodstream like a spirit inside him.”12

Wakefield also benefited from advice from other members of the knuckleball fraternity, including Charlie Hough and Candiotti, who taught him how to change speeds, pick spots with hitters, and be patient when it didn’t work. Wakefield “paid it forward” to knuckleballers who came after him, notably R.A. Dickey.13

On April 20, just as the 1995 major-league season was to begin (after the players’ strike which had prematurely ended 1994), the Pirates released Wakefield. Six days later, the Boston Red Sox took a flyer and signed him to a Triple-A contract. Red Sox GM Dan Duquette had seen Wakefield pitch when Duquette was GM for the Montreal Expos. He had a pitching staff in Boston that needed renewal and bolstering. Duquette’s appeal to Wakefield was based in part on an arrangement to hire Phil Niekro as a consultant and offer to set the young pitcher up with him. Wakefield said, “Boston was the only team to make me a decent offer.”14

Called up in time to pitch on May 27, he made back-to-back starts on May 27 and, on two days’ rest, May 30. Wakefield had one of his best years with the Red Sox in 1995. He finished the season with a 2.98 earned run average. He won his first four starts – two of them complete games, allowing just two earned runs over 34 innings. And he kept on winning – even taking a no-hitter into the eighth inning twice, on June 9 and July 9 – until the point he was 14-1 (1.65) in mid-August.

But the knuckleball teaches humility. August 18 was a horrific game in which he was so wild the Mariners took the first 18 pitches he threw, and then – on his second swing – Mike Blowers hit a grand slam. Knuckleballers are prone to giving up homers, though; in his career, Wakefield surrendered 418, or one every 7.7 innings.

Including that outing, he was 2-7 over the rest of the season, losing the last four games he started. Despite the ups and downs, The Wall Street Journal wrote in late September that Wakefield was having “one of the best knuckleball seasons of all time.”15 The Red Sox finished first in the AL East, but were swept in the Division Series by the Cleveland Indians. Wakefield lost Game Three, 8-2. His key contribution to getting the team to the postseason was recognized; he placed third in voting for the Cy Young Award. He had been 16-8 (2.95), leading the team in victories.

There followed a couple of so-so years. In 1996 he was 14-13 (5.14). He then went to arbitration over salary differences with the Red Sox, and prevailed. In 1997, after a swollen elbow put him on the 15-day disabled list in April, he was 12-15, despite an improved 4.25 ERA. His 15 losses were the most in the AL.

Clearly, the team around any pitcher matters a great deal. In 1998, the Red Sox reached the postseason again. Wakefield’s ERA was 4.58, but in wins and losses he was 17-8. Boston faced the Indians again in the Division Series. This time, Wakefield pitched in Game Two. He lasted only 1 1/3 innings, was bombed for five runs, and took the loss.

Closer Tom Gordon was injured in 1999, so the Sox used Wakefield as a swingman. He started in stretches and relieved in others. As a closer, he saved 15 games in 18 opportunities. There was one remarkable inning on August 10 in Kansas City when he managed to tie a major-league record by striking out four batters in one inning (the 10th); he also blew a save in the game.

Was the knuckleball just one pitch in his repertoire? He’d answered that question years earlier, talking to Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune: “No, basically, I’m a one-pitch pitcher. Here it is. If they hit it, they hit it.”16

One of the lessons he had learned, he said, was “Don’t pitch to the names.”17 In other words, don’t worry about the strengths and weaknesses of whoever might be in the batter’s box. Just try and get the ball over the plate and let the knuckler’s unpredictable movement perform its magic. As much as anything Phil Niekro taught him, it was that throwing the knuckleball required a degree of psychological fortitude, to be able to maintain self-confidence and faith. No one knew how the ball was going to flutter; “use that uncertainty to your advantage.”18 When he was pressing, sometimes it meant he was throwing the ball too hard. Teammate Mike Greenwell noticed this once and told him, “Ease up a little. Don’t put so much pressure on yourself. You’re trying too hard…Try taking a little off.”19

The Red Sox made it to the postseason yet again in 1999, and Wakefield worked in two games in the Division Series, for a total of two innings, giving up three earned runs.

Wakefield wasn’t pleased about being assigned to the bullpen in 2000, at almost the last minute. “It’s hard to swallow two days before the season starts and all the work I’ve put in. I don’t see any reasoning for it.”20 In some key respects, Wakefield’s record in 2000 (6-10, 5.48) was almost a carbon copy of 1999’s (6-11, 5.08). In 2000, however, Derek Lowe became Boston’s full-time closer. Wakefield received only one save opportunity and failed to convert it.

Wakefield started 17 games for the third straight year in 2001. He brought his ERA down to 3.90; his record was 9-12. He’d seen a few managers come and go in Boston, and felt that Jimy Williams was made a scapegoat for a dysfunctional clubhouse in 2001. Replacing Williams with pitching coach Joe Kerrigan was, unfortunately, a short-term move that saw the club get worse.

Wakefield’s autobiography (published in 2011) is an exceptionally honest one, admitting to uncertainty and vulnerability. The Red Sox took advantage of his versatility, sometimes perhaps a bit too much. Ballplayers in general tend to benefit from routines, and particularly with regard to certainty as to their role. Wakefield went through numerous changes, of managers and of roles, and even of ownership when the Henry/Werner/Lucchino group purchased the ballclub in early 2002. In some ways, he felt, “My whole career has been in a state of flux.”21

In 2002, under new manager Grady Little, Wakefield started the season being told he would be working in the bullpen. “I’m not upset about it. I accept it,” he said. “That’s the way things are around here.”22 When it came down to it, though, his first two appearances were starts. By season’s end, he had started 15 games and relieved in 30 others, with three saves in five chances. Despite the three different roles, his ERA in 2002 was 2.81 and he posted an 11-5 record. His mixed roles in the years 1999 to 2002 may have cost him as many as 20 or more wins, which would have secured his standing as the winningest pitcher in Red Sox history.

In November 2002, Wakefield married Stacy Stover, whom he had met in Massachusetts. The couple had two children, Trevor and Brianna. Stacy has been an active supporter of the Jimmy Fund. She also worked with Wakefield’s Warriors, a group associated with the Franciscan Hospital for Children in Boston which gave children the opportunity to come to Fenway Park, watch batting practice, and meet some of the players.

In 2003, Wakefield returned to starting, almost exclusively. With rare exception, and a bump in 2010, he remained a starter for the remainder of his career. He never achieved better than his 4.09 ERA in 2003 over those final nine years. He was 11-7 during the 2003 regular season, nine of the wins coming while starting.

After a three-year gap, Boston got back to the postseason once more in 2003. Wakefield started and lost Game One of the Division Series, but then blossomed in the ALCS against the Yankees. He won Game One, 5-2, working six innings as the starter. He also started and won Game Four, 3-2, giving up just one run in six innings.

Game Seven took place three days later. It pitted Pedro Martinez (Boston) against Roger Clemens (Yankees); the score was tied, 5-5, after eight. Mike Timlin got the Yankees 1-2-3 in the bottom of the ninth. Manager Little called on Wakefield to pitch the bottom of the 10th and he got them 1-2-3. Wakefield threw just one pitch in the 11th, and it was the one he would most like to get back. Third baseman Aaron Boone hit a game-winning home run which sent the Yankees to the World Series and sent the Red Sox home for the winter. “It wasn’t supposed to end like this,” Wakefield said. “It’s difficult, period. We are brothers in here. We have been family going on nine months and it hurts.”23

Alluding to the team’s stunning loss in Game Six of the 1986 World Series, Wakefield also told Red Sox clubbie Joe Cochran, “I just became Bill Buckner.”24 Though he apologized to Red Sox fans afterward, hardly anyone blamed Wakefield or thought poorly of him. Indeed, at the Boston Baseball Writers dinner over the winter, Wakefield received a standing ovation from the thousand or more fans in attendance.

This was – almost – the nadir for Boston in the long rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees, right up there with the “Bucky Dent” single-game playoff loss for the AL East title in 1978. Here it was 25 years later, and the Sox had still never beaten the Yankees in a high-stakes matchup.

The true nadir came a year later in the 2004 League Championship Series, after the Yankees took the first three games, trouncing Boston in Game Three, 19-8. Wakefield had been 12-10 during the regular season, eating innings again. In Game Three, after New York had already scored nine times, he volunteered to relieve even though he had been slated to start Game Four. He pitched 3 1/3 innings midgame, more than any other Boston pitcher that day, and was touched for five runs. In doing so, he took one for the team, foregoing his start. Doug Mirabelli, Wakefield’s “personal catcher,” said, “You don’t want your bullpen to get blown out….For him to be able to go out there and suck up some innings for us, that was a huge help.”25

When it came to Game Four, the Red Sox pulled out a win with some magic in the ninth and then more magic in the 12th. Game Five ran even longer, and Wakefield pitched the 12th, 13th, and 14th innings. He was the winner when David Ortiz – for the second night in a row – delivered the game-ending hit.

The Red Sox won the next two games and the series; that team is still the only one in MLB history to climb back from a 0-3 deficit in the playoffs. One moment Wakefield treasured the most came not long after the Red Sox had won Game Seven and eliminated the Yankees. As the celebration in the clubhouse was winding down, he was told he had a phone call. It was the Yankees’ manager calling. “He said, ‘Wake, this is Joe Torre. I just wanted to congratulate you. You’re one of the guys over there that I respect. Just remember to have fun. You guys deserve it.’ Afterward I wrote him a note and told him how much that meant to me. That’s one of the highest compliments you ever get from an opposing manager at that point…It really touched me deeply for him to call me.”26

Boston then swept the World Series over the St. Louis Cardinals, breaking an 86-year-old “curse.” Wakefield appeared only in Game One. He started, and though the Red Sox supported him with seven runs, he gave up five in 3 2/3 innings and got no decision. It was the last time he pitched in 2004.

Wakefield was 16-12 (4.15) in the 2005 regular season, the winningest pitcher on the staff. His best game was a complete-game 1-0 loss to the Yankees on September 11, a three-hitter in which he struck out a career-high 12 New Yorkers. Boston returned, briefly, to postseason play, getting swept in the Division Series by the eventual World Series winners, the Chicago White Sox. After the Red Sox lost the first two games on the road, Game Three was at Fenway Park. Wakefield was the starter and loser; in the top of the sixth, Paul Konerko hit a two-run homer off him to give Chicago a 4-2 lead. The final score was 5-3.

Experience had proven that it takes a certain talent to be able to corral the knuckleball – some handled Wakefield’s better than others. Boston’s first-string catcher, Jason Varitek, experienced considerable difficulty with the knuckler. Other catchers caught Wakefield over the course of his career, and it was always a challenge. Doug Mirabelli used an outside softball catcher’s glove. Victor Martinez wound up using a first baseman’s mitt, the better to help him snare the ball.

Nonetheless, that December, the Red Sox traded Mirabelli to the San Diego Padres for Mark Loretta. After Wakefield started the 2006 season 1-4, the Sox reacquired Mirabelli on May 1. Thanks to a State Police escort from Logan Airport – Mirabelli changed into his catcher’s gear in the back seat of a car – the catcher arrived at Fenway just in time to handle Wakefield for a start against the Yankees. The Sox won the game, but with four runs in the bottom of the eighth, just after Wakefield had left the game. He won his next two starts, but lost two months in the second half of the season to a stress fracture in his rib cage. He finished the season losing his last three decisions and was 7-11 (4.63).

Though his ERA edged up to 4.76 in 2007, once again the team around a pitcher truly helps. Wakefield was 17-12 that year, second in wins on the Red Sox only to Josh Beckett (20-7). He became a World Champion again, as the Red Sox rolled over the Colorado Rockies with a sweep in the World Series.

Recurring problems in the back of his shoulder problems kept Wakefield inactive for nearly two weeks in August. As a result, he was kept off the roster for the Division Series and the World Series.27 His only appearance during the postseason was a start in Game Four of the ALCS against Cleveland. He gave up five runs, and bore the defeat. Maybe he could have pitched once in the World Series, but he asked, “Are you going to get 100 percent out of Tim Wakefield? I don’t know that…It’s not fair for the rest of the 24 guys in that clubhouse for me to put them through that.”28

He pitched in just one more postseason game. In the 2008 regular season, though he brought his ERA down to 4.13, his won/loss record was 10-11, fourth in wins among the Red Sox starters behind Daisuke Matsuzaka, Jon Lester, and Beckett. (That August, another Wakefield knuckleball disciple, Charlie Zink, pitched his lone major-league game for Boston. Ironically, it came because Wakefield was on the DL again with a stiff shoulder.29) Wakefield’s one appearance in the playoffs was in Game Four of the ALCS against the Tampa Bay Rays. He gave up five runs in 2 2/3 innings and lost the 13-4 game. Including his two wins for the Pirates, this left him with a postseason record of 5-7 (6.75).

In 2009, once again Wakefield won in double digits for the Red Sox in the regular season, 11-5 (4.58). Only Beckett and Lester won more. That year, Wakefield was named by Tampa Bay’s Joe Maddon to the American League All-Star team, the only year in which he earned the distinction. He didn’t appear in the game, a 4-2 AL win.

Wakefield was below .500 in his final two seasons: 4-10 in 2010 and 7-8 in 2011. Both years, his ERA was over 5 (5.34 and 5.12). After winning his 199th career game on July 24, it took eight more starts until he won #200, his last, on September 13. Only six other knuckleballers have reached that milestone as of 2023.30

Wakefield was just six wins short of the franchise record for wins, and during the final week of the season, he told Fox Sports that the fans “deserved” to see him break it. However, the team’s new general manager, Ben Cherington, said that while he respected the veteran, he had to be honest with him about his chances of making the team.31 Wakefield decided it was time to call it a career, saying, “I’m still a competitor. But ultimately I think this is what was best for the Red Sox and I think this is what’s best for my family and, to be honest with you, seven wins isn’t going to make me a different person or a better man.32 His total of 3,006 innings pitched for the Red Sox ranked first, 230 innings more than second-place Clemens.

Longevity of tenure had a lot to do with Wakefield racking up 186 wins for the Red Sox. When he finished his career, he’d pitched 17 seasons for Boston. He was one of only 19 pitchers in major-league history to have spent 15 or more seasons with a single franchise.33

There had been some other honors along the way. In 2010, Wakefield won baseball’s Roberto Clemente Award, given to the player who “best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team.”

From June 2012, Wakefield worked as a studio analyst for the New England Sports Network (NESN) broadcasts of Red Sox games, frequently offering pregame and postgame commentary. He is the Honorary Chairman of the Red Sox Foundation and hosts a number of events such as the foundation’s annual celebrity golf tournament. He has also continued to help other knuckleballers develop their craft, notably Steven Wright, who became an AL All-Star in 2016 for Boston.34

Tim Wakefield died of brain cancer on October 1, 2023, at just 57 years old. Red Sox Charman Tom Werner was among many who offered tributes to the man who had spent 29 years in the organization as a player, special assistant, and broadcaster. “It’s one thing to be an outstanding athlete; it’s another to be an extraordinary human being. Tim was both. He was a role model on and off the field, giving endlessly to the Red Sox Foundation and being a force for good for everyone he encountered.”

On February 27, 2024, Stacy Wakefield died of pancreatic cancer. On Opening Day of the 2024 season, as the Red Sox planned to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the magical 2004 championship, the team chose to honor both Stacy Wakefield in pregame ceremonies.

Sources

A major source for this biography was Tim Wakefield’s autobiography, Knuckler: My Life with Baseball’s Most Confounding Pitch. In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Knuckleballer Tim Wakefield retires,” ESPNBoston.com, February 18, 2012. http://www.espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/7585718/tim-wakefield-retires-17-seasons-boston-red-sox

2 Tim Wakefield with Tony Massarotti, Knuckler: My Life with Baseball’s Most Confounding Pitch Knuckler (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2011), 37.

3 Knuckler, 37.

4 Knuckler, 37.

5 “A First Baseman Takes the Mound,” New York Times, May 4, 1992: C2.

6 Associated Press, “Pirates Rookie Doesn’t Knuckle Under in Debut,” Evansville Courier and Press, August 1, 1992: 17.

7 Mike Hiserman, “Pirates’ Wakefield Wins Game of the Decade,” Los Angeles Times, August 27, 1992: C1.

8 Jack O’Connell, “Rookie Knuckler is Pirates’ Hope,” Daily Advocate (Stamford, Connecticut), October 9, 1992: 17. Already Wakefield was attracting attention in Boston. See Michael Madden, “He Thrived During White-Knuckle Time,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1992: 72.

9 Associated Press photo caption, Marietta Journal, May 28, 1993: 23.

10 Danny Gallagher, “Tim Wakefield Floats Like A Butterfly to Cy Young Award,” St. Albans (Vermont) Daily Messenger, August 23, 1995: 23.

11 “Around the Majors,” Washington Post, July 10, 1993: C4.

12 Quoted in Knuckler, 73.

13 Jeremy Repanich, “R.A. Dickey, Tim Wakefield, Charlie Hough and the Art of the Knuckleball,” Sports Illustrated Kids, September 27, 2012. http://www.sikids.com/node/11953316

14 Danny Gallagher. Wakefield was initially placed with Boston’s Fort Myers team in the Gulf Coast League; Phil Niekro was working there at the time managing the Colorado Silver Bullets.

15 Stefan Fatsis, “Gnarly Knuckleball Enjoys Overdue Season in the Sun,” Wall Street Journal, September 29, 1995: B9.

16 Jerome Holtzman, “Wakefield Resists Knuckling Under to Pressure,” Chicago Tribune, October 13, 1992: B5.

17 Knuckler, 62.

18 Knuckler, 81-83.

19 Knuckler, 109.

20 “For Demoted Wakefield, Bullpen Isn’t A Relief,” Washington Post, April 4, 2000: D4.

21 Knuckler, 148.

22 Bill Ballou, “Wakefield Accepts Bullpen Role,” Worcester Telegram & Gazette, February 26, 2002: D4.

23 Bill Finley, “From Brink of Pennant to Brink of Despair,” New York Times, October 17, 2003: D4.

24 Knuckler, 178.

25 Author interview with Doug Mirabelli, May 17, 2013.

26 Author interview with Tim Wakefield, May 8, 2013. Wakefield’s memories of the 2004 season appear throughout the book by Allan Wood and Bill Nowlin, Don’t Let Us Win Tonight: An Oral History of the 2004 Boston Red Sox’s Impossible Playoff Run (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2014). This particular quotation is on page 202.

27 Amalie Benjamin, “He’s Left Off the Roster Because of Ailing Shoulder,” Boston Globe, October 24, 2007: D4.

28 Benjamin.

29 “Fellow Knuckleballer Zink to Start for Wakefield,” USA Today, August 11, 2008.

30 Ahead of him were Phil Niekro (318), Ted Lyons (260), Joe Niekro (221), Charlie Hough (216), Jesse Haines (210), and Eddie Cicotte (208).

31 Peter Abraham, “Sox’ Wakefield Announces Retirement,” Boston Globe, February 18, 2012: C1.

32 Ian Browne, “Emotional Wakefield Announces his Retirement,” MLB.com, February 17, 2012. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/26730038//

33 Knuckler, 7.

34 Michael Hurley, “Steven Wright Credits Tim Wakefield For Much Of Success With Red Sox,” CBS Boston, July 6, 2016. http://boston.cbslocal.com/2016/07/06/steven-wright-credits-tim-wakefield-for-much-of-success-with-red-sox/

Full Name

Timothy Stephen Wakefield

Born

August 2, 1966 at Melbourne, FL (USA)

Died

October 1, 2023 at Hingham, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.