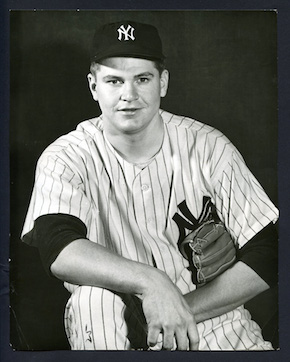

Bob Turley

Bob Turley was a rich businessman who once won a Cy Young Award pitching for the Yankees. “Bullet Bob” was one of the hardest-throwing pitchers of the 1950s and one of the wildest of any generation.

Bob Turley was a rich businessman who once won a Cy Young Award pitching for the Yankees. “Bullet Bob” was one of the hardest-throwing pitchers of the 1950s and one of the wildest of any generation.

Turley’s business success far surpassed his baseball accomplishments. His top baseball salary was $35,000, but he earned millions in insurance and finance, and built a castle in Florida worthy of a 21st century superstar. “The business world is the same as playing on a championship team,” he said. “You’ve got to put your winning team together and you’re going to win.”1

Robert Lee Turley was born in Troy, Illinois, on September 19, 1930, the second child of Delbert and Henrietta Turley. The family moved to East St. Louis, Illinois, when he was two months old. Delbert worked in a meatpacking house. After his parents divorced, Bob lived with his mother.

His first organized baseball team was sponsored by a funeral home in a junior chamber of commerce youth league. Bob was a big, strong boy—too big and strong to suit some of the players’ parents. He was banned from pitching as a 12-year-old. In his freshman year at East St. Louis High, the baseball coach refused to play him, so he quit the team and didn’t return until he was a junior. As a teenager he more than held his own pitching against adults in the local municipal league.

He attended a Yankee tryout camp with his uncle, Ralph Turley, who was about two years older. Bob impressed the scouts, and one of them made a note to follow up on “R. Turley.” Looking in the phone book, he found the listing for Bob’s grandfather and asked if there was a pitcher in the family. Sure, the grandfather said, my son Ralph. “R. Turley,” check. The Yankees signed Uncle Ralph.

Just across the Mississippi River, the St. Louis Browns had had their eye on Bob since he worked out at Sportsman’s Park and signed him on the night that he graduated from high school in June 1948. He received $200 a month in his first professional season, plus $1.75 a day for meal money on the road. The Browns sent the 17-year-old to Belleville in the Class D Illinois State League. Ralph was with the Marion club in the same league. After Bob pitched against the Marion Indians, he joined Ralph for dinner and found his uncle packing his gear; he had been released. Ralph said, “They told me they signed the wrong Turley.”2

Bob compiled a 9-3 record in two months with Belleville, but he walked 71 batters in 97 innings, setting the tone for his career. For the next three years he climbed through the Browns’ farm system, racking up dazzling strikeout totals and alarming walk totals. He won 23 games in Class C ball in 1949 and 20 as a 20-year-old in the fast Double-A Texas League in 1951. Turley was named the league’s outstanding pitcher after striking out 200 and walking 142 in 268 innings for San Antonio. He struck out 22 in a 16-inning tie game against Tulsa. (That night’s pitching matchup was Bob Turley vs. Bob Curley.)3 When the Texas League season ended, Turley joined the last-place Browns and made his big league debut on Sept. 29. He held the White Sox to one hit in the first five innings before he tired and gave up six runs in an 8-3 loss.

Turley’s 21st birthday present was a draft notice. To avoid being drafted, he enlisted at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, where the commanding officer wanted him for the baseball team. Teammates included Dr. Bobby Brown, Don Newcombe, and Gus Triandos. During the 1952 army season, according to contemporary accounts, he struck out 215 in 115 innings and pitched a no-hitter. While in the service he married Dollie Weaver.

He rejoined the Browns in August 1953, finding the club where he had left it two years earlier: in last place. The Browns had one decent young pitcher, Don Larsen; one decent old pitcher, Harry Brecheen; and one decent really old pitcher, Satchel Paige. Turley served notice that the sorry team had a new ace. He struck out 61 in 60 1/3 innings. His record was only 2-6, but he gave up no more than four earned runs in any of his starts. One of his victories was a 12-inning, three-hit shutout. By his 23rd birthday, he had grown into a beefy, intimidating presence at six-foot-two and around 215 pounds.

The Browns were failing on and off the field. They lost 100 games and drew fewer than 300,000 fans in 1953. Owner Bill Veeck was broke. The team ran out of new baseballs in its final game and had to finish with scuffed batting-practice balls. Other American League owners, determined to rid themselves of the maverick Veeck, forced him to sell the franchise before they would approve a move to Baltimore.

Turley pitched the Orioles’ home opener in 1954, the first major league game in Baltimore since 1902, following a parade that jammed the city’s streets. He struck out nine White Sox in a 3-1 victory. In his next start, he struck out 14 Cleveland Indians and carried a no-hitter into the ninth before a single and a home run beat him.

Collier’s magazine clocked his fastball at 94.2 miles per hour, using a DuMont cathode ray oscilloscope. He said he wasn’t at full strength because he had pitched a complete game two days before the test.4 (Bob Feller had once been timed at 98.6 mph by a different instrument.) Turley’s was a live fastball, with sharp movement that made it hard to hit as well as hard to control.

His control vanished in midseason. In consecutive starts he walked 11, then nine, then 11 again. Next he passed five out of 11 batters in the first two innings. Three weeks later he walked a dozen in 6 2/3; no big-league pitcher has ever issued more bases on balls in fewer than seven innings. He said he threw 212 pitches in one complete game.

The 1954 Orioles were, after all, still the 1953 Browns. They lost 100 games again, but more than one million fans turned out in their new home town. Turley finished 14-15 with a 3.46 ERA, leading the league with 185 strikeouts, 181 walks, and just 6.5 hits allowed per nine innings. Despite his wildness, he was dominating opposing batters. The new manager and general manager, Paul Richards, told him, “We’re going to build this team around you.”5

Six weeks later Turley was at home in the Baltimore suburb of Lutherville, feeding his new baby son a bottle and watching the “Tonight” show, when his picture popped up on the screen in a news bulletin. Richards had traded him to the New York Yankees in the biggest deal in major league history. He was the centerpiece of a 17-player swap. Baltimore got veteran outfielder Gene Woodling, shortstop Willy Miranda, pitchers Jim McDonald and Harry Byrd, and two Triple-A catchers, Hal Smith and Gus Triandos, in exchange for Turley, Don Larsen, and shortstop Billy Hunter. Eight other minor leaguers also changed hands. The Yankees thought they had the right Turley this time.

Baltimore fans erupted. “Richards must have lost his mind,” one said. Another thought, “It’s like trading skilled mechanics for laborers.”6

Turley recalled, “The next morning, when I went out to the car, someone had written ‘Damn Yankee’ on it in the dust.” When he got over the shock, he saw opportunity: “I’d have crawled to New York.”7

The Yankees had won five straight World Series from 1949 through 1953, but 1954 was “the year the Yankees lost the pennant.” They fell to second behind Cleveland. The New York Times’s Arthur Daley wrote, “The Bronx Bombers clinched next year’s pennant yesterday by whisking away from the Baltimore Orioles two youthful strong-armed pitchers and a flashy shortstop in exchange for no one they’ll miss.”8

Turley said walking into the Yankee clubhouse for spring training in 1955 was “the scariest time of my life.” He soon realized that the men wearing pinstripes weren’t seven feet tall, but they were united by a single purpose: “We all wanted to be in the World Series, and you could just feel it and sense it.”9

When the regular season opened, Turley lived up to the hype by winning his first five starts, all complete games. He missed a no-hitter against the White Sox when his former minor league catcher, Sherman Lollar, singled in the second inning for the only hit. He struck out 46 in his first 45 innings. Then his control deserted him. In his sixth start, he walked eight. Then eight again, then nine. On June 12 he held the defending champion Indians to three hits through five innings before he blew up, allowing four homers and 10 runs. He had other games like that, when he’d be overpowering hitters until he suddenly imploded. Manager Casey Stengel usually relieved him before too much damage was done. Turley’s erratic season closed with a disappointing 17-13 record, but he compiled a 3.06 ERA with six shutouts, a league-low 6.1 hits per nine innings, and a career-high 210 strikeouts. He also led the league in walks.

The Yankees reclaimed their usual place atop the standings in 1955 but lost the World Series to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Starting Game Three in Ebbets Field, Turley gave up two home runs to Roy Campanella and didn’t make it out of the second inning.

His problems carried over into 1956. The question around the league was “What’s the matter with Turley?” He said he was weak after losing nearly 20 pounds during the offseason. Stengel lost confidence in him, and he started only 21 games, completing just five. His 8-4 record was testimony to the powerful Yankee lineup; his ERA ballooned to 5.05 and he walked seven per nine innings, the worst of his career. “You had to baby him a little bit,” Yogi Berra said. “You know, he’d get a little wild. You had to go out there and say, ‘C’mon, Bob, you’re better than that.’”10

In September Turley was dropped from the starting rotation. Pitching coach Jim Turner urged him to try a no-windup delivery. Teammate Larsen had adopted it because he had been tipping his pitches. Turner thought it would help Turley’s control. The so-called no-windup is the short, simple delivery used by most 21st century pitchers, but it was revolutionary in 1956, when many pitchers kicked their front legs high before throwing. Stengel suggested the effect was psychological, “on the pitcher, who thinks he has a magic weapon, and on the batter, who thinks he is up against a very dangerous new thing.”11

When the Yankees and Dodgers met again in the World Series, Turley was stuck in the bullpen. After Brooklyn won the first two games, Stengel bypassed him and started Whitey Ford on two days’ rest. In Game Five, Larsen’s new delivery baffled the Dodgers and, as the Daily News’s Joe Trimble wrote, “The imperfect man pitched a perfect game.”12 With the Yankees up three games to two, Stengel apparently thought that since the no-windup had worked once, maybe lightning would strike twice. He chose Turley to start Game Six.

Turley called it the best game he ever pitched. He struck out 11 Dodgers, getting Campanella three times. “Man!” Campy said. “When you see me take three swings at three fastballs and not even foul tip one, the fellow throwing ‘em must have something. Maybe he was using a little gun to fire that ball up there.”13 Turley and Brooklyn’s Clem Labine pitched shutout ball for nine innings, as the Dodgers managed only three hits. Labine set down the Yankees in order in the tenth. In the bottom half, after Turley walked two (one intentionally), Jackie Robinson smacked a liner to left. Enos Slaughter misjudged the ball and it sailed over his head to bring home the winning run. The Yankees rebounded the next day to win the championship.

The sterling World Series performance was not enough to win back Stengel’s confidence. For the first two months of the 1957 season, Turley served as a spot starter and reliever before injuries forced the manager to put him into the rotation. He had regained the lost weight, building himself up to around 220 pounds. A sportswriter, who had been a track athlete, taught him to take deep breaths to relax. With the no-windup delivery, his control improved dramatically; he walked 4.3 per nine innings, a career low, while registering a league-leading 7.8 strikeouts per nine. In July and August he reeled off 24 consecutive scoreless innings. Opposing batters hit .194 against him and his 2.71 ERA was fourth best in the league. With a 13-6 record in 23 starts, he looked like the ace the Yankees had hoped for.

Turley started Game Three of the World Series at Milwaukee. He loaded the bases in the first but struck out Joe Adcock to escape without a score. Staked to a 3-0 lead, he gave up a run in the second and filled the bases again. He had walked four and thrown a wild pitch. Stengel brought out his quick hook and pulled him from the game.

Turley pitched the final scoreless inning in relief of Ford as the Yankees lost Game Five. After a travel day, Stengel sent him to the mound for the sixth game, with New York facing elimination. He held the Braves to four hits in a 3-2 victory. The Yankees lived to play another day, but Milwaukee’s Lew Burdette shut them out in the decisive Game Seven for his third win of the Series.

Turley’s dominance continued into 1958, the season of his life. “Everything came together,” he said.14 He won his first seven starts, all complete games, including four shutouts and a one-hitter. His strikeout rate fell as he relied more on his curve and slider, but he was pitching deeper into games, completing 19 of 31 starts. He ran his record to 13-3 in July and started the All-Star Game in Baltimore, his adopted home town. It was a disaster; he was knocked out in the second inning after giving up three runs.

The Yankees cruised to their fourth straight pennant, although they slumped in the second half. Turley finished 21-7, led the league with 6.5 hits allowed per nine innings, and won the Cy Young Award. He was second to Boston’s Jackie Jensen in the MVP voting.

He ran into another disaster when he started the second game of the World Series. Milwaukee leadoff man Bill Bruton greeted him with a home run. He pitched to only five batters, getting one out, and was charged with four runs as the Braves scored a record seven times in the first inning.

The Braves won three of the first four games, and the Yankees were on the verge of losing their second straight Series to Milwaukee when Turley started Game Five. He responded with a five-hit shutout, striking out 10. After one day off, he relieved in the 10th inning of the sixth game and got the last out as the Yankees won again to even the Series. The next day, Larsen started Game Seven, but Turley replaced him with two men on in the third. He escaped without giving up a run, then pitched shutout ball until the sixth, when Del Crandall’s home run tied the score at 2-2. Stengel stuck with his ace. Turley allowed only one more hit over the final three innings while the Yankees rallied to win the game and the championship. Turley took home the Corvette as the Series MVP.

A panel of writers and broadcasters awarded him the $10,000 diamond-studded Hickok belt as the Professional Athlete of the Year. At 28, he was on top of the sports world.

Besides his pitching, Turley helped the Yankees with his mastery of baseball’s dark arts. He could call opponents’ pitches. He maintained that every pitcher tipped what was coming with some movement of his hands or body. For example, Early Wynn set his hands differently for his fastball, knuckler, and curve. Connie Johnson moved to the opposite side of the rubber to throw his screwball. Turley read those “tells” from the dugout and signaled Yankee hitters with a loud whistle. Mickey Mantle was an especially enthusiastic listener.15

Turley picked up his Cy Young Award in a ceremony on Opening Day in 1959, then shut out Boston on two hits. The season went downhill from there for him and his pinstriped teammates. The Yankees sank to last place in May. Turley hit bottom on May 26 when he walked eight Red Sox and his record fell to 3-6. Stengel demoted him to the bullpen in August as his ERA rose close to 4.50. “Last year he pitched like Cy Young,” wrote Dick Young of the New York Daily News. “This year he pitches like Dick Young.”16 The Yankees finished third with Turley contributing an 8-11 record and 4.32 ERA. Stengel said, “He don’t smoke, he don’t drink and he don’t chase around none. But he can’t win as good as that drunk [Larsen] I got.”17

What happened? One opposing player said Turley couldn’t get his breaking stuff over, so hitters were sitting on his fastball. Turley thought the fastball had lost some movement. The next spring This Week magazine timed several pitchers with high-speed cameras. Turley registered 90.7 miles per hour, three-and-a-half mph slower than the 1954 test under different conditions, but hardly a junk-baller’s pace. (Baltimore’s Steve Barber and Los Angeles’s Don Drysdale topped 95.)18

Turley opened the 1960 season with a sore back and started only once in the first month. In midseason his elbow began hurting. He spent time in the bullpen, going nearly two months without a complete game. He finished 9-3 with a 3.27 ERA, but his strikeout rate fell off a cliff to 4.5 per nine innings, below league average. As he reached his 30th birthday in September, he acknowledged, “I’m just not that fast any more. I have to do other things to help that fastball, and then it’s all right.”19

The Yankees reclaimed first place and faced Pittsburgh in the World Series. Turley started Game Two, a 16-3 Yankee blowout, but he staggered through 8 1/3 innings, allowing 13 hits. He struck out nobody, the only time in his career that he pitched more than six innings without a strikeout.

Although the Yankees battered Pirates pitching, the Series went to a seventh game. Stengel chose Turley to start rather than using Ralph Terry on three days’ rest. Turley threw only 20 pitches before he left the game in the second with his elbow aching. Bill Mazeroski’s ninth-inning homer sent the Yankees home losers.

Ralph Houk succeeded Stengel as manager in 1961. By June 1 he had seen enough of the struggling former ace, buried him in the bullpen, and pretty much wrote him off. In July x-rays revealed bone chips in Turley’s elbow. He went on the disabled list for a month, but was put back on the roster for the World Series. That was a courtesy based on past services rendered; he did not pitch in the Series as the Yankees defeated Cincinnati. Houk said later, “His arm was gone…. He was a power pitcher and he’d lost it and it never did come back.”20

After the Series, Turley underwent surgery to remove the bone chips. He was not ready for Opening Day in 1962, but in May he declared, “My arm is 100 percent okay.”21 By August he was denying rumors of retirement. He pitched only 69 innings and did not appear in the World Series against San Francisco. When the Series was over, and the Yankees had won again, he emptied his locker and took his uniform number 19 home with him. He knew he wouldn’t be wearing it again.

Turley went to Puerto Rico for winter ball. He believed he needed to pitch regularly to strengthen his arm and regain his rhythm. He had been there just two days when a telegram informed him that the Yankees had sold him to the Los Angeles Angels in a contingency deal: The Angels would pay if he was able to pitch.

“I’m convinced I’ve got enough stuff to get by,” he said when he reported to spring training in 1963.22 His first victory for the Angels was a three-hit shutout of Minnesota, with nine strikeouts. “I didn’t walk a man,” he said. “I’m proud of that because it’s the only time I ever did it in my life.”23 He didn’t get his second win until a month later, but it was a gem. Pete Ward’s sixth-inning single was the White Sox’ only hit. It was Turley’s fourth career one-hitter and his 100th victory. Despite his 3.30 ERA, the Angels released him in July to make way for younger pitchers.

The Boston Red Sox picked him up, but he pitched effectively only once in seven starts. Boston released him after the season and hired him as pitching coach under manager Johnny Pesky. That job lasted just one year.

Still only 34, Turley was regretting his decision to retire. “I should not have quit because I could still throw good,” he said years later. “But I hadn’t been pitching enough … to stay in major league condition.”24 He got another chance from Paul Richards, who had traded him away from Baltimore and was now general manager in Houston. Richards invited him to spring training with the Astros in 1965, but he was cut before Opening Day.

Driving from Florida home to Maryland, he stopped in Atlanta to visit a friend and ran into John McHale, general manager of the Milwaukee Braves. McHale hired him as pitching coach for the Triple-A Atlanta farm club. The next year, when the big league Braves moved to Atlanta, Turley was invited to transfer with their Triple-A team to Richmond, but he had started working as a stockbroker and was involved in real estate development in Georgia. He left baseball for good.

Turley’s career arc mirrors those of other young phenoms from Smoky Joe Wood to Mark Fidrych to Mark Prior, shooting stars who lit up the heavens, then “lost it and it never did come back.” But Turley’s life had a second act, one of the most successful of any former athlete.

As a young player, Turley had opened an insurance agency in the Baltimore area in partnership with Orioles catcher Gus Triandos and an experienced agent. He found that he loved business “with a passion.”25 After he moved to Atlanta in the ‘60s, he went back into insurance along with his real estate investments. He came to believe that term life insurance, which covers the policyholder for a fixed number of years, was a better fit for most customers than whole life, or cash-value, insurance. Two companies fired him because term life, with lower premiums, was less profitable.26 He lost most of his real estate and other businesses, and filed for bankruptcy.

He met a fellow agent, Art Williams, who shared his view of the insurance business. In 1977 Williams led a group of seven principals who founded A.L. Williams & Associates. Williams was a balding, drawling former high school football coach with a preacher’s cadence and a salesman’s confidence. “We were a bunch of people that wanted to be somebody,” he said. “We wanted to make a difference in our lives. We wanted to do something for our families.” Williams built the company into the largest insurance sales organization in America. At raucous pep rallies for the sales force, he chanted, “Just do it. Do it. And do it. And do it until the job is done.”27

A.L. Williams was a multilevel marketing business, like Amway and Mary Kay cosmetics. Top executives recruited salespeople, who recruited others, who recruited others, and the high-level agents took a cut of each team member’s commissions. Art Williams said Turley’s greatest impact in the early years was “to give credibility to A.L. Williams” because of his fame.28 Turley was an effective recruiter; his own nationwide sales team grew to 20,000 people. He traveled in his private jet named Bullet Bob. A.L. Williams merged with Primerica Corp. and branched out into other financial services, making its original investors millionaires many times over.

“Most successful people are driven because they want to prove something to somebody,” Turley said. “They’re not in it for money. They are driven because they want to prove something to someone, maybe a mother, a father, a brother, a coach who told them you’re no good, [you] never could do it.”29 Who was Turley trying to prove it to? Probably the Yankees, who he thought had dumped him when he could still pitch. His son Terry says, “He took great delight in coming to [Yankee] old-timers games and being one of the most successful Yankees ever.”30

Turley had bought a winter home on Marco Island, near Naples, Florida, and indulged his hobby of buying and selling houses. He and his third wife, Carolyn Dawson, built an opulent 13,500-square-foot stone mansion with a 500-pound chandelier and a replica of a Michelangelo painting on the ceiling of its grand entrance hall. The Turleys called it Casa Nel Sole, “our house in the sun;” locals called it the Turley Castle. He told an interviewer that just one of the many palm trees ringing the house had cost more than his 1955 World Series check.

After a divorce from Carolyn, he remarried his second wife, Janet, in 2009. They had two children together, son Troy, who died young, and daughter Rowena. Turley had two sons, Terry and Donald, from his first marriage.

Turley contracted liver cancer and died at 82 on March 30, 2013, in Atlanta. His friend Andy Young said, “Every time I went to see him, even in the last days, in the nursing home, in the hospice, every time he’d look up, he would say, ‘Boy, didn’t we have some fun.’”31

Notes

1 Bob Turley interview with Bill Stevens, February 3, 2003, Naples, Florida. SABR Oral History Committee.

2 Bob Turley interview with Dan Austin, January 28, 1992, Naples, Florida. SABR Oral History Committee. This story sounds too pat to be true, but Bob Turley stuck with it for more than 50 years.

3 Frank Jackson, “Major achievements in minor league ball,” The Hardball Times, April 5, 2013.

http://www.hardballtimes.com/main/major-achievements-in-minor-league-ball/

4 Tom Meany, “Turley’s Fast Ball: 94.2 mph,” Collier’s, June 25, 1954, 42-43.

5 Stevens interview.

6 Associated Press-New York Times, November 19, 1954, 28.

7 Stevens interview.

8 New York Times, November 19, 1954, 30.

9 Austin interview.

10 Primerica tribute video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Inv6djoSoic. Accessed February 10, 2015.

11 The Sporting News, March 13, 1957, 12.

12 New York Daily News, October 9, 1956.

13 New York Times, March 30, 2013, A16.

14 Austin interview.

15 The Sporting News, May 14, 1958, 3.

16 Peter Golenbock, Dynasty (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975), 246.

17 New York Times, September 9, 1959, 54.

18 Tim Wendel, High Heat (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2010), 112.

19 The Sporting News, October 5, 1960, 13.

20 Ralph Houk and Robert W. Creamer, Season of Glory (New York: Putnam, 1988), 144.

21 The Sporting News, June 9, 1962, 7.

22 Associated Press-Baltimore Sun, February 19, 1963, S19.

23 Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, July 20, 1963, C2.

24 Austin interview.

25 Brian Jensen, Where Have All Our Yankees Gone? (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade Publications, 2004), 278.

26 Terry Turley interview, February 10, 2015.

27 Art Williams, 1987 speech to the National Religious Broadcasters. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fOyNap86O_Y, accessed February 10, 2015.

28 Primerica tribute video.

29 Stevens interview.

30 Terry Turley interview, February 24, 2015.

31 Primerica tribute video.

Additional sources

Bill Madden, “Former Yankees hurler Bob Turley dies at 82,” New York Daily News, March 30, 2013. http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/yankees/yankees-pitcher-bullet-bob-dead-82-article-1.1303733, accessed July 2, 2014.

Rich Marazzi, “Bullet Bob Turley,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 7, 2000.

Obituary, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 6, 2013, online archive.

T.S. O’Connell, “Out of Left Field,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 21, 2003.

Sporting News annual guides, provided by Mike Galbreath and Andrew North.

Bob Turley with Tim Cohane, “With the Yanks, You Win or Else,” Look, March 29, 1956.

“Bob Turley, Cy Young winner and seasonal Marco resident, dies at 82,” Naples (Florida) Daily News, April 1, 2013, online archive. Accessed July 2, 2014.

Full Name

Robert Lee Turley

Born

September 19, 1930 at Troy, IL (USA)

Died

March 30, 2013 at Atlanta, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.