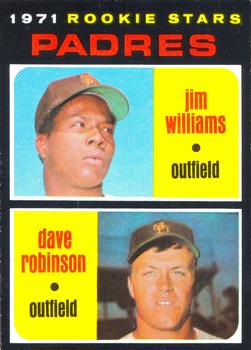

Dave Robinson

Dave Robinson was the first player signed by the San Diego Padres in 1968. The National League expansion team’s press conference on July 31 featured Hall of Famer Duke Snider, a fellow Southern Californian who had inadvertently discovered Robinson at San Diego State College.1 “He told me he went out to see [outfielder] Jim Nettles [younger brother of third baseman Graig Nettles] and then he came back telling everyone about me,” said Robinson.2 For San Diego, it was the first step in assembling the team that would open the 1969 season in eight months.

Dave Robinson was the first player signed by the San Diego Padres in 1968. The National League expansion team’s press conference on July 31 featured Hall of Famer Duke Snider, a fellow Southern Californian who had inadvertently discovered Robinson at San Diego State College.1 “He told me he went out to see [outfielder] Jim Nettles [younger brother of third baseman Graig Nettles] and then he came back telling everyone about me,” said Robinson.2 For San Diego, it was the first step in assembling the team that would open the 1969 season in eight months.

It was a joyous ceremony for Robinson, a graduate of nearby La Jolla High School and a baseball star at San Diego State. Ironically, Robinson had nowhere to play. Normally players chosen in the June amateur draft signed contracts and were quickly shuttled to a low-level minor league team. However, like their expansion brethren Montreal Expos, Kansas City Royals, and Seattle Pilots, the Padres had no minor-league teams — so Robinson had to wait until 1969 to start his professional career.

David Tanner Robinson was born on May 22, 1946 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He was the second child of John and Kathleen (Tanner)3 Robinson. An older brother, John, Jr., was born two years earlier. Younger brother Bruce, who played major-league baseball for the Athletics and the Yankees, was born in 1954. John Robinson received his law degree from the University of Minnesota and was a Navy officer. He was transferred with his family to San Diego in 1950. Upon his retirement from the Navy, he worked in the banking industry.

The Robinsons lived in La Jolla, about 12 miles north of downtown. John Robinson shared his passion for baseball with his family. When he lived in Minneapolis, he was a fan of the Triple-A Millers; in San Diego, he coached youth baseball for 17 years.4 “He loved baseball a lot,” said Dave. “He got me started…I made the ‘A’ League team when I was seven.” From that early age, Robinson competed against older players.

Mother Kathleen was at home and operated the “twirl-around,” the family baseball hitting aid. “My mom would stand in the middle of the yard with a rope and a ball on the end,” said Robinson. “We drilled a hole in the ball. She’d twirl that thing around for hours and hours… She’d get blasted by the ball sometimes and she just kept doing it.”

In high school Robinson was a multi-sport athlete, lettering in football, wrestling, and baseball. In ninth grade, at 95 pounds, he wrestled, ran cross country, and played junior varsity baseball. As a sophomore he lifted weights and gained 25 pounds but was still undersized for football. “I was so far down the depth chart that they didn’t have any more plastic helmets,” he said. “I had to use a leather helmet. They called them “Thorpies” for [early 20th century football star] Jim Thorpe.”

Robinson continued to play baseball through high school, but after growing to five-ten and 160 pounds as a senior, his talent emerged on the football field. In October 1963, during his first varsity season, he was named starting quarterback for the La Jolla High Vikings after a few games. A month later he was named the city’s “Prep of the Week” by the San Diego Union after the team’s third consecutive win. Robinson completed 18 of 26 passes for 230 yards and two touchdowns.5

Dave also enjoyed practicing and playing football with his brother Bruce. “He’d have his football uniform on and try to run past me and I’d stick my arm out and trip him.” Bruce entered the National Football League’s youth “Punt, Pass and Kick” competition annually and won the regional competition seven years in a row.6

In baseball, Dave was twice named to the All-Western League team.7 In tenth grade the lefty-throwing outfielder became a switch-hitter. His Colt League coach was the father of Ken Henderson, then a Giants outfielder. Joe Henderson said, “Dave, there’s nobody in the big leagues who throws left-handed and hits right-handed.”8 So Robinson converted.

Robinson’s high school career batting average was .3679 but he showed little power. “I always had a great arm and I was fast,” he said, “but I really didn’t have a whole lot of pop in high school.” As a result, his only college sports scholarship offers were to play football at University of California, Berkeley and Missouri State — if he made the team.

Robinson decided to attend San Diego State, where most of his friends were going. He played junior varsity baseball in 1965. The next year he played varsity for Coach Lyle Olsen, whom Robinson called “the best coach I ever had.” Olsen reached Triple-A in the Dodgers chain at shortstop in the 1950s while Pee Wee Reese owned the position.

Unfortunately, Robinson’s sophomore playing time was limited by a back injury sustained while representing his fraternity in the intramural wrestling finals. “I didn’t play much,” said Robinson. “I was in pain. I hit over .400 but only in about 20 at bats.”

As a junior in 1967, by then six-feet-one and 180 pounds, Robinson had a breakout year. Before practice he would meet Aztec senior Mike Everett in the batting cage for intense hard-toss drills at a distance of about ten feet. “We’d hit a ball into the net. Then two seconds later another one. And two seconds later another one,” said Robinson. “Just rapid fire…He’d pitch to me and then I’d pitch to him. We really got strong doing that…I really got some pop in my bat.”

Robinson responded to the demanding defensive workouts of Coach Olsen. “He’d get out behind second base,” he said, “and I’d be in center field, and he would work me out until I’d almost threw up. He’d hit a ball to my right. I’d have to circle it and come in the right way towards the base and catch the ball and throw it towards the base I was going to. And then he’d hit one to my left, then over my head and he wouldn’t give me any time to rest.”

The 1967 Aztecs had their highest California Collegiate Athletic Conference finish (second) in six years behind the bats of Everett and Jim Nettles, who between them led the team in every major offensive category.10 Robinson hit .475 in conference games and was named co-MVP with pitcher Bob Cluck, a future major-league pitching coach. He was also selected to the All-Conference First Team and All-NCAA District Eight second team. That summer he was invited to join the Basin League, based in Nebraska and South Dakota — at that time the nation’s top college summer baseball league, and frequented by big-league scouts.11

Packed with his baseball gear for his trip to the Midwest was an NCAA football provided by Aztecs football coach Don Coryell. Robinson’s success as a high-school quarterback had been reinforced by his two years of fraternity football. Word spread to Coryell, who twice took Robinson to dinner with his assistant John Madden, who also went on to great success as an NFL head coach. During informal workouts, Robinson impressed the coaches while passing to future NFL Pro Bowl receiver Haven Moses. Also on Robinson’s mind as he prepared for his two-month trip was being away from his girlfriend Connie Carr.

In the Basin League, Robinson played for the Valentine (Nebraska) Hearts. He lived in the basement apartment of his host family’s home. He received a small weekly stipend for maintaining Veterans Memorial Field. “My job was to take care of the field, the infield, batter’s box, drag the field,” said Robinson.12

“It really helps when you are playing every day,” said Robinson of the experience he gained that summer. “You find out what your weaknesses are, and you work on those and get stronger.” Robinson hit .318, second in the league. He became team MVP and was named to the all-star team.13

Upon his return to campus, Robinson said, “I gave back the football [to the coaches] and told them I think I have a future in baseball.” He also established his family future, marrying Connie in November.

In 1968 Robinson was named Aztecs MVP again as the team finished third in the conference. He hit .325 with four home runs and 23 stolen bases, while setting school records with 16 doubles and 68 hits. He had a perfect 1.000 fielding percentage in the outfield.14 His .347 career average was fourth all-time in the program’s history (for up to 350 at-bats).15

On June 6, Robinson was selected in the seventh round of the amateur draft. (The four expansion teams were granted selections from the fourth to 19th rounds.) Robinson was one of seven hometown San Diego players selected by the Padres among their 16 June draftees. He was the first to sign a contract on July 31; the pact included a $10,000 bonus and incentive payments for promotions to Double-A, Triple-A, and the majors. Major League Baseball had given the four expansion teams a jump start in assembling players even though they had no operating minor-league teams.16

“After I got drafted I needed a job,” said Robinson. Thus, he returned for his third summer to the Del Mar Race Track. He was a busboy at the prestigious Turf Club, and chatted with Hollywood celebrities like Hollywood’s John Wayne, Mickey Rooney, and Carol Channing, as well as FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The Padres senior staff also dined at the Turf Club. “I would see [team President] Buzzie Bavasi and [general manager] Eddie Leishman almost every day,” said Robinson, who told them, “‘This is almost strange. I should be playing baseball and here I am waiting on you guys.’ They said, ‘Teams are going to start next year.’” So, Robinson worked out on his own with a friend throwing batting practice.

The excitement of reporting to the Padres spring training in 1969 faded quickly. “The first thing they tell me is to change my hitting style, which totally affected me for the next two years. I never hit close to what I did in college ball,” said Robinson. “I kind of hit like (Carl) Yastrzemski with my bat wrapped back around. All of a sudden I can’t do that anymore. I have to hit with my hands back like most people do.”

Assigned to the Elmira Pioneers, a Double-A cooperative team shared by the Padres and Kansas City Royals,17 Robinson’s extra base power disappeared. He had only 21 extra base hits in 444 at-bats, with a slugging percentage of .322. “I cooperated with them,” said Robinson, “because of my manager in Double-A, Harry Bright. If I didn’t do what they told me to do I’d hear about it. I followed directions and hit .255.”

His power and batting average notwithstanding, Robinson was an offensive contributor to the expansion team’s success and near-.500 record (70-71-1). His 96 walks were fourth in the Eastern League; his .388 on base percentage led the team and was seventh in the league. He had 25 stolen bases.

Defensively, Robinson had to transition to a new position. “They put me in left field,” said Robinson. “Jerry Morales was the center fielder. I could field circles around him. All the players on my team said I was the best outfielder. Nevertheless, Robinson led Eastern League outfielders in fielding percentage, was fourth in assists with 13, and tied for the lead in double plays with four.

Pioneer first baseman Jeff Pentland,18 a professional scout and coach for over 20 years, including four stints as a major-league hitting coach, said, “His tools were well above average on everything he did.” Defensively, Pentland said that Robinson had “one of the best arms I ever was around. He could stand at home plate and throw the ball over [the] center field [fence].19

Robinson played in 142 games for the Pioneers, even though 140 were scheduled. One game was replayed because of a tie.20 The other extra game was played in error — Elmira and Waterbury had so many postponements the teams played a make-up game that was not needed.21

“I remember all the doubleheaders,” said Robinson. Despite the postponements, many games were played unless there was steady rain, he said, including one at Wahconah Park in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, against the Pittsfield Red Sox. The Housatonic River was just beyond the outfield fence and it had overflowed its banks. “A ball was hit to left field and the river was in left field,” said Robinson. “The ball was flowing away from me and I had to run after the ball.”22

In 1970 Robinson was promoted to the Padres’ brand new Triple-A team in Salt Lake City, managed by Don Zimmer. “I loved playing for Zimmer. He was a great guy for me,” said Robinson. The manager allowed Robinson to modify his stance and moved him back to center field, adding to his comfort in Salt Lake City. “I had basically adjusted to what they had told me to do,” said Robinson. “I created a hybrid style which was in between both [stances].”

Robinson’s power returned. He had 41 extra-base hits in 445 at bats, including 13 home runs, 17 doubles, and 11 triples. He led the Bees in triples and was second in homers and RBIs.23 Robinson had a hitting target at Derks Field. “There was a sign in right-center field. ‘Continental Airlines — the proud bird with the golden tail.’ and I used to aim for that,” he said. “That was my triple area.”

That summer the Robinson family visited Salt Lake City. Sixteen-year-old Bruce, a highly regarded high school catching prospect as a sophomore, joined the Bees for pregame drills. “I put on a Padres Triple-A uniform and went out and took batting practice” said Bruce. “I hit home runs left-handed and right-handed. At Salt Lake City the ball jumped. I said to myself, ‘I can do this.”’24

The PCL season ended on August 29. Robinson headed home to San Diego. He was not called up by the Padres on September 1. when the active roster could be expanded to 40 players. He moved into his parents’ home with Connie and two-year old son David. At midday on September 9, Robinson had returned from the beach and his mother told him the Padres had called. “They said, ‘You need to be at the ballpark today,” said Robinson. “I went from wearing a bathing suit that day to wearing a uniform.”

Robinson’s first appearance was on September 10 as a defensive replacement for left fielder Al Ferrara in the eighth inning of a Padres home win against Atlanta. Two games later, against Cincinnati, his family was in the stands at San Diego Stadium. Robinson was in the starting lineup, hitting seventh and playing left. In the top of the second Robinson settled in the batter’s box. “I looked down. There’s Johnny Bench [catching]! I’m going ‘My God!’ said Robinson. “Pete Rose is out there. The Big Red Machine.”

Unflustered, Robinson worked a walk off Tony Cloninger. In the fifth he singled to right off Cloninger for his first major-league hit and stole second. He later singled again and was walked intentionally. He started again the next night, hitting seventh and playing center field. He recorded his first RBI on a force play and had a single.

After coming off the bench for four games, he started six of the Padres’ last seven games, hitting second in all but one. In a four-game spurt he went 7-for-16. It started in San Francisco, where he homered in consecutive games. On September 25 he hit a ninth-inning solo home run off Giant lefty Skip Pitlock, notching his second RBI of the night in a 7-4 win. The next day he hit a two-run homer off Hall of Famer Juan Marichal to give the Padres a lead they held into the ninth inning. Ken Henderson, son of Robinson’s Colt League coach, contributed two RBIs when the Giants rallied for the win.25

Robinson’s 15-game 1970 record for the Padres was strong: a .316 batting average, a .395 on-base percentage, and a .922 OPS in 38 at-bats. He had two doubles, two homers, and six RBIs. He added two stolen bases. “I felt that I can do this,” said Robinson. “I saw the ball real well. Hit the ball real well. Played pretty good in the outfield. I ran the bases good. I thought ‘This is not that much different from AAA.’”

In 1971 spring training, Robinson was one of many contenders for an outfield position. He said. “There were eight outfielders going for five spots.” Newspapers reported conflicting observations from manager Preston Gomez. On March 21, according to one newspaper, Gomez said that Robinson would be one of three outfielders who “probably will receive more seasoning in the minors.”26 Another on March 23 reported that Gomez said Robinson would be given “a solid chance to win the job.”27 But information from Gomez was rare, said Robinson, “He hardly ever spoke to me…I don’t know that I even had more than five words with him.” Still, “The last cut was between John Sipin and myself,” he said, “and I made it.”

In the Padres’ first 14 games Robinson was limited to seven pinch-hitting appearances. He went hitless, facing Hall of Fame pitchers in four of those at-bats: Gaylord Perry (twice), Juan Marichal, and Bob Gibson. He drew a walk on April 21 off Bill Singer.

On April 25, the Padres had a doubleheader in Atlanta. After the first game, Gomez called Robinson and Ron Slocum into his office and told them they were being sent to the team’s new Triple-A affiliate, Hawaii. “We had to sit in the stands for the second game,” said Robinson.

The Hawaii Islanders were set in the outfield. “When I got there all the outfielders were hitting over .300 and I couldn’t break into the lineup,” said Robinson. “I understand that. It was frustrating. I gained a lot of weight. I went to the beach every day and I went to the ballpark and sat on the bench.” Through June, Robinson had two singles in 22 at-bats in 21 games with only seven defensive appearances.

On July 1 Robinson was loaned to Evansville, the Milwaukee Brewers’ Triple-A team. “They thought I played first base. I never played first base in my life.” He played one game at first for the Triplets, making one error in three chances. He returned to the outfield and played 46 more games, hitting .240 with three home runs, 18 RBIs, and an OPS of .631.

Robinson prepared well for 1972 and reported for spring training. “I was hitting the ball so hard and one day they call me in and tell me they are going to send me to Class A.” That was the Kinston (North Carolina) Eagles. a New York Yankees affiliate.

“I could see the handwriting on the wall of this ball club. I’m not going anywhere,” said Robinson. He would turn 26 in May, a month after his second child was expected. He also needed nine credits for his college degree. It was time to move on from baseball. Pentland, who also played with Robinson in Salt Lake City, said, “If you look at his major-league record, I think the Padres gave up on him early.”

Robinson hit only two career home runs, just the ninth switch-hitter to hit exactly one career home run from each side of the plate.28 Robinson is the only one (of 16) to do it in consecutive games with one off a Hall of Famer.

For the next three years, while raising his family and finishing his degree at San Diego State, Robinson worked construction, sold cars, and went door to door as a Fuller Brush salesman. He added courses to earn his teaching certificate and coached freshman football at Mt. Miguel High School in Spring Valley.

Meanwhile, brother Bruce, a lefty-hitting catcher, was a first-round draft pick in 1975. He reached the majors with Oakland in 1978, making the Robinsons the 282nd brother combination to play in the majors.” 29 He played with the New York Yankees in 1979 and 1980.

During the summer of 1975, Robinson completed his student teaching experience and was hired as a physical education teacher at a middle school just a few miles north of the Mexican border. At Mar Vista Middle School, many student families were in transition and in need. Its multi-racial student body regularly heard Robinson’s message: “With hard work you can do whatever you want.”

Robinson as gym teacher leveraged the running craze that was sweeping the country and became an informal cross country coach. Every gym class began with a half-mile run and after Friday’s timed 1.5-mile run, he posted student times on a leaderboard. “They wanted to see their name move up,” said Robinson. “Then if they broke nine minutes they got their picture taken.”

“Robinson’s Road Runners,” a group of student long-distance runners, joined their teacher for a six- to eight-mile run before classes. Robinson met students on weekends at Cowles Mountain, the highest viewpoint in San Diego at 1,593 feet. They would run to the peak, 1.5 miles with a 1,000-foot elevation gain.

“He came in and he was the bomb for all of us,” said Will Guarino, a seventh grader in 1977. “It gave everyone a motivation to work, train and be together, to be friends, to be brothers. He basically broke down color barriers and brought us closer together.”

The middle school running program had a citywide athletic impact, said Robinson. “I’d take my kids to [non-school] cross country meets around the city and they’d win everything. They’d win all the age groups. Boys and girls.”

When Robinson’s students got to high school, those schools won San Diego city championships. “A lot of teachers and kids told me later on they probably would have dropped out of school after tenth grade,” said Robinson, “but they were interested and went out for cross country in high school.”

Guarino’s parents died when he was a high school junior, and in that time of need, Robinson was there. “The first 30 days, when there was no money and I was trying to figure it all out, he took me to the Social Security office, to the Red Cross, to figure out where I could get some money.” Guarino said Robinson prepared him “to survive in life and not give up even if your parents aren’t around.” Today Guarino is married and has three children. He is in his 16th year at Division I University of San Diego as head coach for men’s and women’s Cross Country and women’s track.

Guarino’s seventh-grade training partner also received a boost from Robinson. Guarino and Matt Clayton trained in 1977 to run a marathon with the goal of breaking the 13-year-old age group record of 2:57. A twisted ankle kept Guarino out of the race, so Robinson ran with Clayton. As they crossed the finish line together in 3:04, the race announcer proclaimed, “Here comes the first father/son team,” said Robinson.

As a college runner, Clayton said, “It all started in junior high. Coach Robinson doesn’t get much publicity, but he gave us great background in our formative years. Who knows what would have happened without running?”30 Clayton earned All-America cross country recognition at San Diego State in 1987,31 ran a 2:14 marathon in 1991, and ran in the U.S. Olympic Trials in 1992 and 1996.32

Student Mark Dearing was motivated by Robinson’s “Superstars” competition, where students competed in athletic events, just like the long-running television series. In the seventh grade, Dearing lived with his adoptive grandmother in Imperial Beach, known for its gangs and drugs.33 “The two people that drove me were Coach Robinson and Grandma,” said Dearing. Life lessons Robinson taught through sports propelled Dearing, a Robinson Superstars award winner, as he wrote in an autobiography. 34

“Everything was a competition,” said Dearing, recalling Robinson’s advice. “Anything you do, you are going to have to be better than other people.” Dearing earned a PhD in education and for 30 years has worked in the fields of education, social services, and community development.35 “I wouldn’t be the man I am or had the success I’ve had if not for him,” said Dearing. “I have one baseball card,” he said, “and it’s his.”

Robinson’s formal coaching career began in 1980. He was coach of track and cross country at Mar Vista High School from 1980 to 1987. From 1987 until 1990 he was the track and cross country coach at Southwestern Community College in adjacent Chula Vista.

In the early 1980s Robinson set a goal of running a marathon in under three hours. It took about six tries. “As soon as I broke three hours I wasn’t going to run marathons anymore. The training took too much time,” he said. A few years later one of his track athletes at Mar Vista High suggested to Robinson that they enter the local decathlon. “I stunk it up but I liked it,” said Robinson of the ten-part track and field event. It appealed to his athleticism.

In March 1985 Robinson broke the unofficial36 decathlon record at age 38 with 6,386 points, winning the USA Masters (over 35) Track and Field Championships at Occidental College in Los Angeles. That summer, in San Diego, he set another unofficial record, this time for 39-year-olds, with 6,450 points. He lost by just 62 points to Rex Harvey, who holds the Masters record for the most decathlon competitions and most points lifetime.37

Robinson fell short of his goal to be the first Masters decathlete to reach 7,000 points, just 500 points below the (all-age) Olympic Trials qualifying threshold.38 “I never had a chance to run track because it was the same time of year as baseball in high school,” said Robinson, reflecting about choosing baseball over track. “I made the right choice because I got to the big leagues and hit a few home runs and got on a few baseball cards. That’s a dream of a lot of people.”39

Robinson later took up cycling and competed in the Senior Olympics, and became a competitive tennis player and scratch golfer. One of his greatest achievements, he said, was dunking a basketball at 40. His decathlon training made it possible. “People say you can’t run faster and can’t jump higher. That’s not true,” he said.

After 30 years as a teacher, Robinson retired in 2005. He lives in San Diego with his wife Connie. His son, daughter and families live nearby. He continues to run up Cowles Mountain, as he did 40 years ago with his students.

The professional career of the San Diego Padres’ first player was shorter than Robinson had hoped — just 367 games (22 at the major-league level) in three years. Still, it was “a blessing in disguise,” he said, because being an athlete helped him get hired as a teacher.40 Will Guarino agreed. “The benefit of it all came to us as a community.”

Last revised: April 8, 2021

Author’s Note

The author first contacted Dave Robinson in 2018 while researching a story about his playing in an unscheduled minor league game in 1969 for the Elmira Pioneers. He found Dave through his brother Bruce, a musician and former MLB player. In 2019 the author wrote Bruce’s SABR biography. In 2020 the author self-published a story about Bruce’s invention of the Robbypad, a flexible throwing shoulder protector attached to a catcher’s chest protector. In late 2020 the author reconnected with Dave to write his SABR biography.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Tom Larwin of the Ted Williams (San Diego) Chapter of SABR for forwarding several stories about Dave Robinson from the San Diego Union. Also, thanks to Cassidy Lent, Manager of Reference Services of the Baseball Hall of Fame, for her assistance in providing Dave Robinson’s Hall of Fame file, and for her ongoing assistance with my baseball research.

This biography was reviewed by Paul Proia and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin,

Sources

All quoted information attributed to Dave Robinson was provided in telephone interviews detailed below.

Dave Robinson telephone interviews, December 21, 2020 and January 4 and 29, 2021.

Will Guarino telephone interview, January 5, 2021.

Jeff Pentland telephone interview, December 21, 2020.

Larry Agrella, telephone interview, December 29, 2020.

Allan Simpson, telephone interview, January 4, 2021.

Mark Dearing, telephone interview, January 27, 2021.

Other primary sources were: Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Padres Sign Ex-Aztec Outfielder Robinson,” San Diego Union, August 1, 1968, 21. San Diego State was known as San Diego State College until 1972 when it changed its name to California State University, San Diego. Two years later it became San Diego State University.

2 Nettles was selected by the Minnesota Twins as the 16th pick in the fourth round of the draft, seven slots before the first Padres draft pick at number 23.

3 Robinson’s middle name, Tanner, was his mother’s maiden name, according to his parents’ Virginia marriage certificate.

4 Mark McCarter, “Experience Helps Bruce Aid Lookouts Attack,” Chattanooga Free Press, June 12, 1977.

5 Wayne Lockwood, “La Jolla Back Prep of the Week,” San Diego Union, November 18, 1963: 28/

6 Bruce Robinson text message December 21, 2020.

7 David Robinson, Hall of Fame file.

8 Among the rare exceptions at that time were Cleon Jones and Lee Maye.

9 Hall of Fame file.

10 San Diego Aztecs 2019 Baseball Media Guide.

11 The Basin League was named for the location of its teams, in the Missouri River Basin. In its 21-year history, from 1953 to 1973 more than 130 Basin Leaguers played in MLB. According to Allan Simpson, the 1981 founder of Baseball America, the leading summer college baseball league has shifted over time. In the mid-1960s the Basin League was the preferred destination for summer college players.

12 Robinson prepared the field with his roommate Jerry Feldman, who led the Basin League with nine triples and 44 RBIs. He was drafted by the Angels in 1968 and played as high as Triple-A during six seasons in the minor leagues.

14 E-mail from Jim Solien, Assistant Media Relations Director, San Diego State Athletics, January, 11, 2021

15 As of 2019 he ranked 7th all-time for careers of less than 350 at bats, according to the San Diego Aztecs 2019 Baseball Media Guide.

16 The Padres shared a fall 1968 Arizona Instructional League team with the Seattle Pilots. The team played 48 games. The season ended on November 24, according to the 1969 Baseball Guide. According to Baseball Reference 38 players were on the roster, most from the Pilots. About 16 were Padres and only one, John Preston, was a June draftee. Five were October, 1968 expansion draft picks. The remaining players may have been free agents. Jeff Pentland played on the team but was not aware of the selection process. Robinson was not aware of the team.

17 Most of the Pioneers were Padres. There were a few Royals. Apparently other teams loaned players to Elmira, as Skip Lockwood (Seattle) was on the team.

18 Pentland was signed as a free agent by the Padres, and was the Pioneers’ first baseman. He pitched for Arizona State from 1966-68 with a 32-12 record and a 2.25 ERA. His career totals in victories (32), shut outs (5) and ERA (2.24) are still in the ASU all-time top ten. In 1971 he was a left-handed catcher for 15 games for Lodi of the Single-A California League. He was the hitting coach for the New York Yankees and Los Angeles Dodgers during his 22-year professional coaching career. In 2002 he was inducted into the ASU Hall of Fame.

19 The distance to the 12-foot fence in center field at Dunn Field in Elmira was 386 feet. If Pentland was referring to Derks Field in Salt Lake City, where he played with Robinson in 1970, the distance was 400 feet to the center field wall.

20 Elmira and Pittsfield split 28 games and they had one tie, according to the Official 1970 Baseball Guide, The Sporting News, 434.

21 Official 1970 Baseball Guide, 434.

22 This quote and paragraph are excerpted from the SABR story “August 4, 1969: When Waterbury and Elmira played a minor-league game by mistake written by the author, accessed February 7, 2021.

23 Robinson hit .255 with an OPS of .774.

24 Excerpted from Bruce Robinson’s SABR biography. https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/bruce-robinson/, accessed February 7, 2021.

25 Both nights Robinson was named “Player of the Game” by Padres KOGO radio and was the post-game radio guest.

26 Ferd Borsch, “Gomez Promises Hawaii 2 Good Hurlers,” Sunday Star Bulletin & Advertiser, March 21, 1971, 44

27 Joe Sargis (UPI), “Gomez Welcomes New Spirit on Padres Team,” The [Zanesville, OH] Times Recorder, March 23, 1971, 3B

28 This information was created by the author on January 14, 2021 using the Baseball Reference Season and Career Finder. Results were cross-referenced and verified using Baseball Reference and Retrosheet.

29 Baseball Almanac, https://www.baseball-almanac.com/family/fam1a.shtml, accessed February 7, 2021.

30 Jeff Nahill, “Runners Have a Rough Day at CIF,” Star News Sunday Chula Vista, CA], November 30, 1986, 19

31 “SDSU’s Clayton Earns All-America Honors,” Los Angeles Times, November 24, 1987

32 Association of Road Running Statisticians, Matt Clayton profile, http://arrs.auguszt.in/runner/2652, accessed February 7, 2021.

33 Mark Dearing, telephone interview, January 27, 2021.

34 Alex Amani, A Nomad’s Journey: Lessons From an Eclectic Soul, (Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2010), Chapter Two. Dearing has published three books under the name of Alex Amani.

35 https://www.linkedin.com/in/mark-dearing-edd-40b5a670/, accessed February 7, 2021.

36 Single-age records are unofficial records, according to Jeff Davison, Masters Track and Field History Chair. Official records are kept in five-year brackets. Email from Davison, December 27, 2020.

37 Davison e-mail. Robinson said he finished first at the meet and was presented with the first-place medal. He was later contacted at home and told that Harvey had actually won the meet when the scoring was reviewed.

39 Nahill.

40 Archive Story Corps.org, “Dave Robinson shares his life adventures with his granddaughter,” November 24, 2017, 15:40 of interview, https://archive.storycorps.org/interviews/my-grandpa-dave/, accessed February 7, 2021.

Full Name

David Tanner Robinson

Born

May 22, 1946 at Minneapolis, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.