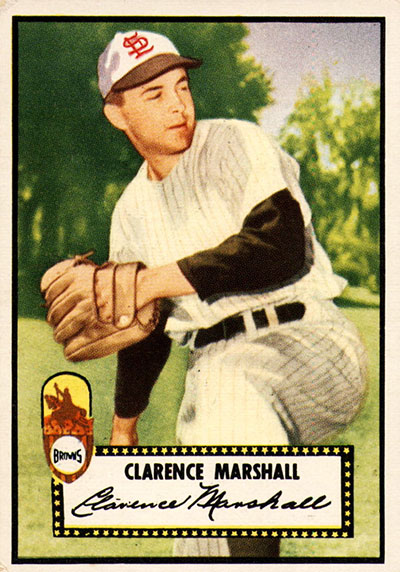

Cuddles Marshall

Baseball has had its share of memorable nicknames, particularly in a bygone era. The moniker ‘Cuddles’ bestowed on Clarence Marshall is certainly one of these. Marshall pitched for the New York Yankees and St. Louis Browns in parts of four seasons between 1946 to 1950. He was a tall righty with a lively fastball but erratic control. Highlights of his relatively brief career included starting the inaugural night game at Yankee Stadium and being a part of the Yankee team that won the 1949 World Series.

Baseball has had its share of memorable nicknames, particularly in a bygone era. The moniker ‘Cuddles’ bestowed on Clarence Marshall is certainly one of these. Marshall pitched for the New York Yankees and St. Louis Browns in parts of four seasons between 1946 to 1950. He was a tall righty with a lively fastball but erratic control. Highlights of his relatively brief career included starting the inaugural night game at Yankee Stadium and being a part of the Yankee team that won the 1949 World Series.

Clarence Westly Marshall was born on April 28, 1925 in Bellingham, Washington. He was the second of three boys born to Clarence and Esther (née Ady) Marshall, following John and preceding Ernest. His father ran streetcars and then operated a gas station while his mother raised the boys at home. Clarence Sr. built the family a home on Elm Street with the help of his sons. Bellingham, a bayside town just 18 miles south of the United States-Canada border, had not produced a major-leaguer until Marshall. Roger Repoz and Ty Taubenheim are the only other big-league ballplayers from Bellingham.

The younger Clarence picked up a baseball at an early age. He got his first glove by winning a contest for collecting Wheaties box tops. “There were two vacant lots next to our house and we’d go and play. The kids would yell out who they were and almost everyone wanted to be Babe Ruth. I was Lou Gehrig. I just liked him,” he recalled in 1999.1 When he was eight or nine, he was helping his mom with chores in the kitchen one day when he exclaimed: “One day I’m going to play for the Yankees and play in the World Series.”2

Clarence attended Bellingham High School, where he played basketball and baseball. He pitched and also played third base. In 1943, his senior season, the hard-throwing right-hander was nearly unhittable. In at least one game he was. On April 15, he struck out 14 and homered while throwing a no-hitter versus Mount Vernon.3 For the season he posted a record of 9-1 and did not allow an earned run.4

After high school graduation, Marshall signed with the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League. The 18-year-old, who was exempt from military service because of a hernia, reportedly held out on signing until he received $2,500.5 Clarence became the second member of his family to pitch for the Rainiers in 1943; his older brother John had played for the team earlier in the year before being released in May. John pitched in the PCL for two more seasons before spending over a decade toeing the rubber for teams in the Western International and Northwest Leagues.

Clarence made his first appearance with the Rainiers on July 5, pitching in relief against the Los Angeles Angels. It was a rough debut against a talented lineup that included eight future major-leaguers, including Andy Pafko. Marshall allowed 10 earned runs while walking eight in 6 1/3 innings.6 He fared better in his second game, another long relief outing, when he allowed two earned runs over innings.7 Marshall made several more relief appearances for Seattle that year and re-signed with the team for the 1944 season. During the off-season he took courses at Western Washington University.

The Rainiers loaned Marshall to the Memphis Chickasaws of the Southern Association for most of the 1944 season. He had a record of 9-5 with a 4.50 ERA in 21 games. Marshall’s teammates with Memphis, an affiliate of the St. Louis Browns, included the one-armed ballplayer Pete Gray and Ellis Kinder.

In December 1944, Seattle manager Bill Skiff traded Marshall to the Yankees for the rights to pitchers Dick Hearne and John Babich.8 The Nashville Banner reported that Yankee scout Johnny Nee had been “sweet” on the young hurler after seeing him pitch with Memphis.9

Marshall spent the 1945 season pitching with Kansas City, a Double-A affiliate of the Yankees. His skipper was Casey Stengel, who had nine losing seasons under his belt as manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Bees/Braves. Marshall pitched in 39 games, completing 15 of 20 starts, compiling a 12-9 record and 4.27 ERA. He racked up 121 strikeouts and issued 107 walks in 173 innings. Following the season, the Yankees purchased Marshall’s contract from Kansas City in preparation for the 1946 campaign.

Marshall reported to St. Petersburg, Florida for his first big-league spring training in February 1946. He was starstruck when he first entered the clubhouse and found his locker between those of Charlie Keller and Bill Dickey.10 Stepping onto the field for the first time, Marshall heard another player asking him to play catch. It was Joe DiMaggio. “The first ball I threw went 20 feet over his head,” Marshall later remembered.11

Marshall broke camp with the big-league club. During a trip to Dallas to play an exhibition game in early April, a reporter overheard some players, including Joe Page, talking about how girls wanted to cuddle Marshall like a teddy bear.12 The reporter used the nickname Cuddles in the paper and it stuck. During his playing career Marshall wished people would just call him Clarence, but later in life he grew to like the name.13

The 1946 Yankees welcomed back DiMaggio after a three-year absence in military service. Their talented lineup also included Keller, Dickey, Phil Rizzuto, and Tommy Henrich. On the pitching side, there were question marks. At 21 years old, Marshall was the youngest member of the staff.

Marshall saw his first action on April 24 in a Wednesday afternoon game versus the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. It was New York’s ninth game of the season. The Yankees had a 5-2 lead in the bottom of the fourth when starting pitcher Randy Gumpert ran into trouble. Ted Williams tripled and Bobby Doerr singled, cutting the deficit to 5-3. After George Metkovich singled to put runners on the corners, New York manager Joe McCarthy called Marshall in from the bullpen. Marshall allowed a sacrifice fly to Hal Wagner before Metkovich was caught stealing to end the inning.

Marshall recorded his first career strikeout when he fanned Eddie Pellagrini to start the fifth. He then walked the bases loaded. Williams strolled to the plate. The Splendid Splinter would win the MVP award in 1946 while hitting .342 with 38 home runs and 123 RBIs. But the rookie got out of the jam by inducing a 4-6-3 double-play off the bat of Williams.

Marshall allowed three hits and a walk in the sixth, but an outfield assist by DiMaggio mitigated the damage. His final line read: 2 2/3 innings pitched, one earned run, five walks, and three strikeouts. Though the American League had established a four-inning minimum for a starting pitcher to be awarded with a win, official scorers occasionally ignored the standard.14 Gumpert was credited with the victory despite only pitching 3 1/3 innings. Marshall would have been the winning pitcher under the modern criteria officially established in 1950.

Marshall picked up his first official major-league win on May 23. He replaced starter Al Gettel with two out and a runner on third in the third inning with the Yankees trailing Detroit, 3-0. Marshall finished out the game, allowing just two earned runs over the final 6 1/3 innings. The Yankee bats came to life, and the Bronx Bombers won, 12-6.

On May 28, the Yankees hosted the Washington Senators in the first ever night game at Yankee Stadium. New player-manager Dickey, who had just replaced McCarthy, made the surprise choice to start Marshall. Dickey based this decision on Marshall’s success pitching in night games with Kansas City.15 A crowd of 49,917 braved cold weather and a chance of rain to watch history.16 Pre-game activities were performed at dusk with Rose Bampton of the Metropolitan Opera House singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” and the two teams standing along the base lines.17 Then, one by one, each tower of the newly installed General Electric floodlights was lit until the field was aglow.18

Marshall walked the first batter on four pitches and then threw two balls to the second hitter. Dickey came to the mound and settled the rookie down. Marshall found his groove and went seven innings, allowing seven hits and five walks while striking out two batters and allowing just two earned runs. Washington starter Dutch Leonard was just a little better, using his knuckleball to hold the Yankees to one run, and Marshall took the loss.

Versus the St. Louis Browns on June 3, Marshall had the best all-around game of his career. He pitched a complete game and allowed just two earned runs to earn the win. At the plate, he collected three hits, all singles, and drove in a run.

In addition to being referred to in newspapers as Cuddles, many mentions of Marshall in the press included references to his good looks. “Handsomest twirler on the staff” was how one reporter described the rookie.19 Another writer referred to him as “pretty boy.”20 Marshall, 6-foot-3, bore a resemblance to Tyrone Power, a popular Hollywood star known for his romantic and swashbuckler roles, including The Mark of Zorro. On June 5, 1946, The Sporting News ran side-by-side pictures of Marshall and Power. The caption under the photos read: “They’re handsome look-a-likes. One is a prominent Hollywood cinema star. The other is a rookie Yankee pitcher. Do you know which is which?”21

After two rough starts against the Detroit Tigers, Marshall was used sparingly in July, first on July 6 and then on July 31. He pitched in 11 games in August and September, including three starts in late September when the Yankees were out of the playoff race. Marshall finished his rookie season with a record of 3-4 and an ERA of 5.33 in 81 innings.

Marshall had the opportunity to pursue another career path after the 1946 season. He was offered a movie contract which would have paid him $250 per week for 40 weeks with a six-year option to earn up to $1,200 per week. “I want to try baseball for another year before making up my mind,” Marshall said at the time.22

During spring training in 1947, new Yankee manager Bucky Harris optioned Marshall to Kansas City, now a Triple-A affiliate. Marshall spent the entire season with Kansas City. He started 25 games and finished the season with a record of 11-6 with an ERA of 4.28 in 166 innings. Control was a problem — he walked 123 batters. Kansas City won the American Association pennant, and the Yankees defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series.

Marshall was again sent to Kansas City out of spring training in 1948. After posting a record of 1-2 with an ERA of 6.69 in 10 games, he was traded to the Newark Bears, another Yankee Triple-A farm team. Marshall fared better with the change of scenery. In 23 games with Newark, he had a record of 9-7 and an ERA of 3.66. He was able to cut down on his walks, allowing 87 in 155 innings. In September, he was called up to the Yankees and pitched a single scoreless inning in the season’s penultimate game.

Coming off a strong showing in Newark, Marshall was in the Yankees’ plans for the 1949 season. Yankees general manager George Weiss gave this quote during the offseason: “We are counting on Marshall to fit into our pitching staff. He is lots better than the Marshall you saw in 1947. For one thing he has a forkball now and can do things with it.”23

Stengel, Marshall’s former minor league manager, was hired as the Yankees’ skipper in 1949. Marshall was shelled in his first two spring training outings, allowing eight runs in three innings.24 In April he spent a week in the hospital with strep throat and did not make his first appearance until May 6.25 He then went on a successful two-month stretch. After picking up a win versus Boston on July 4, Marshall had a record of 3-0 with two saves, and an ERA of 2.76 in 13 games out of the bullpen.

Yogi Berra later shared a story with Marshall’s daughter Barbara when the old batterymates met up at the ballpark in retirement. Stengel would get frustrated by Marshall’s wildness. One game, Marshall was having trouble finding the strike zone and was running deep into counts. He was going to take Marshall out of the game until Berra showed Stengel his hand, which was red and swollen from catching Marshall’s heaters.26

Stengel rewarded Marshall with starts versus the Senators and White Sox on July 8 and July 18, respectively. He allowed a combined nine walks and 12 hits in 11 innings between the two starts, neither of which resulted in a decision. He made six more relief appearances and then started an exhibition game versus Kansas City on August 30 in which he allowed 16 hits in six innings. He threw batting practice in September but did not appear in another game.27 His final ERA for the season was 5.11 to go with his 3-0 record. In 21 games, he walked 48 in innings while striking out 13. Marshall would point out that his erratic control kept hitters from getting comfortable at the plate.28 George Kell reportedly said he preferred to be in the safety of the dugout rather than at the plate when Marshall was pitching.29

The Yankees advanced to the 1949 World Series for their third cross-town matchup against the Dodgers in nine years. Marshall did not appear in the series, which the Yankees won 4 games to 1. His World Series ring was a cherished possession.

Marshall returned home to Washington and spent the off-season working out with Cliff “Lefty” Chambers, a Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher and fellow Bellingham High School alum.30 Marshall also spent the winter working as an instructor with a baseball clinic for coaches that traveled around Eastern Washington and made a stop at Seattle’s Garfield High School to pass along some wisdom to the school’s pitchers.31

In 1950, Marshall was on the Yankee roster to start the season but did not appear in a game. When rosters had to be trimmed to 25 in mid-May, the talent-rich Yankees sold him to the St. Louis Browns for an undisclosed sum.32 Explaining the move to reporters, Stengel said “There is nothing wrong with Marshall’s arm. He simply needs the work that he can get with the Browns and could not get with a one-two club like the Yanks, who must keep their regular starting pitchers working in the rotation.”33

Marshall appeared out of the bullpen for the Browns the day after the transaction was announced. A sore arm then kept Marshall out of action during the first week of June.34 His return to action came in a historic game on June 8 when the Browns visited Boston. The Red Sox scored 29 runs and hit for 60 total bases, both major-league records at the time.35 Marshall pitched in relief and accounted for nine of the runs allowed.

In 28 games for the Browns, Marshall had a 1-3 record and an ERA of 8.05. He again walked almost a batter per inning. “Marshall has a lot of stuff and if we can get him into perfect condition in the spring, he may become a top-notch pitcher,” said Browns manager Zack Taylor. “Cuddles just doesn’t get his curveball over the plate and enemy batters know this. They wait for his fast one and slap it.”36

Marshall took and passed a physical exam for military service before the 1950 season ended.37 The Browns expected to lose him in the Korean War draft and released him to Toronto of the International League on October 12.38 Marshall was indeed drafted in November and served two years in the U.S. Army. He was stationed at Fort Lewis in Tacoma, Washington and pitched for the semipro Bellingham Bells on several Sundays in the summer of 1951.39 He then spent nine months serving overseas in Austria.40 He did not have the opportunity to do much pitching during this period, but he did manage his battalion’s team to a championship.41

Prior to leaving for Austria, Marshall married Margaret Suzow, a native of New Castle, Pennsylvania. The two had originally been set up on a blind date by Margaret’s sister, who worked at a Detroit hotel where the Yankees stayed.42 Clarence stayed in touch with Margaret after she had relocated to California, and the pair tied the knot on June 30, 1951.

Upon Marshall’s discharge from the army, he signed a contact with the Browns for the 1953 season. Manager Marty Marion said he would give the pitcher a chance to make the team, and owner Bill Veeck commented that Marshall would be “a terrific draw on Ladies Day.”43 After pitching with the Browns in spring training, his contract was sold to the Triple-A Baltimore Orioles of the International League on a “30-day trial basis.”44 He pitched in three games with the Orioles, including two starts, before being returned to the Browns.45 In five innings, he allowed eight runs, issued 11 walks, and struck out only two.46

After he was subsequently released by the Browns, the 28-year-old free agent signed with the independent Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League in June 1953.47 He pitched in four games for the Stars, surrendering seven earned runs in three innings, walking seven, and failing to record a strikeout. These lackluster results led to his release on July 30.48

Within a few days, Marshall landed another gig, signing with the Vancouver Capilanos of the Class A Western International League. “I just haven’t had enough work all season,” Marshall told a Vancouver reporter. “In one stretch of 60 days I pitched just two innings. And when you’ve been away for a couple years, it’s work you need.”49

In just his second start with Vancouver, Marshall hurled a no-hitter versus Salem. He was effectively wild — the feat included nine free passes. He finished the season with two wins and three losses for Vancouver.50

A couple of weeks after the season ended, Marshall suffered a fractured leg and hand in a car accident near Bellingham.51 After that he called it quits on his baseball career. His final career major league record was 7-7 to go with 4 saves and an ERA of 5.98. In 73 games, he pitched 185 innings, struck out 69 and walked 158.

Following his baseball career, Clarence and Margaret moved to Los Angeles. They had two daughters: Margaret and Barbara. Clarence worked as a financial analyst for Litton Data Systems for 27 years. He also worked second jobs at a liquor store and then as a security guard at Dodger Stadium to support his family and pay for his daughters’ private school education. The Dodger Stadium gig hardly seemed like work because he got to watch the games and visit with old teammates who came through town. The family eventually settled in Simi Valley in the mid-1960s.52 The elder Margaret passed away in 1976 after an extended illness.

Years after his career ended, Marshall’s image appeared in a Richard Merkin painting titled A Set of Notes in Search of Cuddles Marshall. Merkin was a well-known 20th century artist whose brightly colored works often included jazz musicians, actors, writers, and athletes. He was a regular contributor to The New Yorker, and his works are included in the permanent collections at the Modern Museum of Art and the Smithsonian. He was even on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers’ Lonely Heart Club Band album.53 A 1970 Boston Globe article describes the piece featuring Marshall: “Cuddles, snapshot real, hurls from the focal point of the picture.”54

In 1978, Marshall’s prized 1949 World Series ring vanished. A man doing some work in his home was suspected of having taken it. Twenty-one years later, his daughter Margie’s company paid to replace the lost ring. A 1999 story in the Los Angeles Times documented Marshall’s career and his appreciation for having a replacement ring that looked exactly like the original.55

In 1986, Marshall moved to Saugus, California, where he spent his remaining years. He died on December 14, 2007 at the age of 82. He was survived by his two daughters and a grandson, Jonathan. Fittingly, he was buried in his Yankee uniform at Assumption Catholic Cemetery in Simi Valley.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Barbara Marshall-Housel, Clarence Marshall’s daughter, for sharing information and memories about her father’s life and career.

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Fernando Dominguez, “A Certain Ring,” Los Angeles Times, December 2, 1999: 71.

2 Interview between Barbara Marshall-Housel and the author, December 17, 2020.

3 “Bellingham Youth Tosses No-hit Game,” Spokesman-Review (Spokane, Washington), April 16, 1943: 15.

4 Dominguez.

5 Pete Sallaway, “Sports Mirror,” Times Colonist (Victoria British Columbia, Canada), June 26, 1943: 8.

6 Seattle versus Los Angeles Box score, Seattle Daily Times, July 6, 1943: 19.

7 Hollywood versus Seattle Box score, Seattle Daily Times, July 25, 1943: 5.

8 Alex Shults, “Rainier Shake-up; Hurler is Added,” Seattle Daily Times, December 10, 1944: 18.

9 Fred Russell, “Sideline Sidelights,” Nashville Banner, December 15, 1944: 32.

10 Dominguez.

11 Dominguez.

12 Barbara Marshall-Housel Interview.

13 Barbara Marshall-Housel interview.

14 Frank Vaccaro, “Origin of the Modern Pitching Win,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2013. https://sabr.org/journal/article/origin-of-the-modern-pitching-win/, Accessed November 19, 2020.

15 Joe Trimble, “Yanks Play Tonight; Flock Ditto,” Daily News (New York, New York), May 28, 1946: 467.

16 Jim McCulley, “49,917 See Nats Nip Yanks, 2-1, In Stadium Arclight Opener,” Daily News, May 29, 1946: 355.

17 John Drebinger, “Leonard, Senators, Subdues Yanks, 2-1.” New York Times, May 29, 1953: 26.

18 Drebinger.

19 Jim McCulley, “Dickey, Lights Make Debut at Yankee Stadium,” Daily News, May 29, 1946: 76.

20 Joe Trimble, “Yanks Mop Up Rebels, 11-3, as Rookie Goes 9,” Daily News, April 4, 1946: 53.

21 “Pick the Pitcher — and the Picture Star,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1946: 14.

22 Alex Shults, “From the Scorebook: Cuddles Gets Bid from Films; Hunters Learn to Handle Guns,” Seattle Daily Times, October 15, 1946: 18.

23 Dan Daniel, “Fat Yanks to Find Themselves in the Grease, Weiss’ Warning,” The Sporting News, January 19, 1949: 9.

24 Joe Trimble, “Braves Beat Yanks, 5-3, After Raschi Departs,” Daily News, March 27, 1949: 448.

25 “Clarence Marshall Off Yankees’ Sick List,” Spokesman-Review, April 26, 1949: 13.

26 Barbara Marshall-Housel Interview.

27 Jim McCulley, “DiMag in No Shape to Bolster Yanks,” Daily News, September 29, 1949: 20.

28 Lenny Anderson, “But He’s Still Looking for Work,” Seattle Daily Times, February 14, 1950: 22.

29 Anderson.

30 Wallie Lindsley, “Cliff and Clarence in Tandem Role in Home-Team Talks,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1949: 21.

31 Anderson.

32 “Yanks Sell Marshall, Lindell; Farm Three,” Seattle Daily Times, May 15, 1950: 22.

33 Ray Gillespie, “5 Days’ Grace Makes Gustine 10-Year Man,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1950: 21.

34 Harry Mitauer, “Smash Five Marks and Tie Another; Seven Home Runs Clouted in 28-Hit Attack,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 9, 1950: 21.

35 Mitauer.

36 Ray Gillespie, “Will Zack be Back? His Grin Hints ‘Yes’,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1951: 18.

37 Bob Broeg, “Bucky Harris Keeps Promise with Room to Spare; Sweep of Browns Assures Fifth Spot,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 21, 1950: 26.

38 “Browns Release Three Pitchers to Toronto,” Joplin Globe, October 13, 1950: 10.

39 Bob Schwarzmann, “Major-League Hurler to Work for Bellingham,” Seattle Daily Times, May 6, 1951: 41.

40 Walter Taylor, “Marshall Contented,” Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), April 9, 1953: 44.

41 Clancy Loranger, “’Cuddles’ Marshall Finds Distances Shorter Nowadays,” Province (Vancouver, British Columbia), August 5, 1953: 17.

42 Barbara Marshall-Housel Interview.

43 Jimmy Powers, “The Powerhouse,” Daily News, December 7, 1952: 43.

44 C.M. Gibbs, “Hurler Marshall Returned as Northern Trip Starts,” Evening Sun, May 18, 1953: 29.

45 Gibbs.

46 Gibbs.

47 “Stars Sign Up Pitcher,” Valley Times (Hollywood, California), June 18, 1953: 16.

48 Al Wolf, “L.A. Wins, 5-4 Before 13,153,” Los Angeles Times, July 31, 1953: 60.

49 Loranger.

50 “Cuddles Gets Caps Big Win,” Vancouver Sun, September 5, 1953: 19.

51 “City Baseball Player ‘Good’ After Crash,” Vancouver News-Herald, September 21, 1953: 1.

52 Dominguez.

53 William Grimes, “Richard Merkin, Painter, Illustrator and Fashion Plate, Dies at 70,” New York Times, September 12, 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/13/us/13merkin.html, Accessed 11/24/2020.

54 Robert Taylor, “Like History Under a Strobe Light,” Boston Globe, March 22, 1970: 271.

55 Dominguez.

Full Name

Clarence Westly Marshall

Born

April 28, 1925 at Bellingham, WA (USA)

Died

December 14, 2007 at Saugus, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.