Gary Sheffield

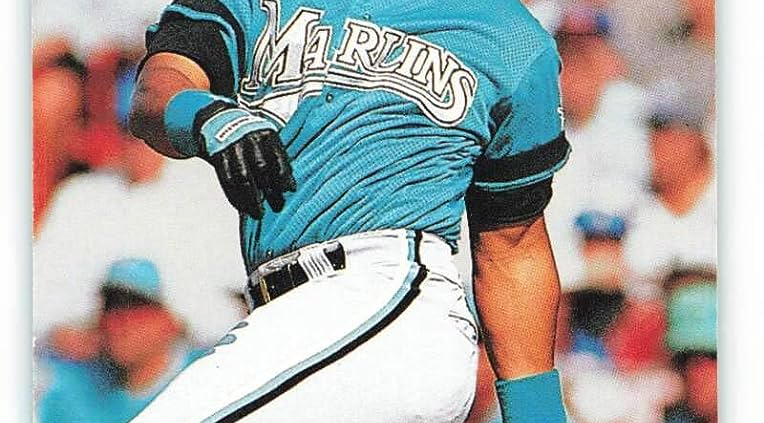

Gary Sheffield was known for a swing so quick “he could turn on a .38-caliber bullet.”1 The menacing way he waggled his bat and the screaming line drives it produced caused a frustrated Cincinnati Reds coach to promise to ban his pitchers from throwing Sheffield a strike.2 Sheffield emerged as a star in 1992, when he led the National League in batting average and was named The Sporting News’ Player of the Year. During a 22-year major-league career (1988-2009), the powerful right-handed batter hit 509 home runs, scored 1,636 runs, drove in 1,676, was a nine-time All Star, and finished in the top 10 in MVP voting six times.

Gary Sheffield was known for a swing so quick “he could turn on a .38-caliber bullet.”1 The menacing way he waggled his bat and the screaming line drives it produced caused a frustrated Cincinnati Reds coach to promise to ban his pitchers from throwing Sheffield a strike.2 Sheffield emerged as a star in 1992, when he led the National League in batting average and was named The Sporting News’ Player of the Year. During a 22-year major-league career (1988-2009), the powerful right-handed batter hit 509 home runs, scored 1,636 runs, drove in 1,676, was a nine-time All Star, and finished in the top 10 in MVP voting six times.

But Sheffield’s personality was as explosive as his bat, and he carried a large chip on his shoulder. He felt he was treated unfairly because he was a Black man, reacted emotionally to perceived slights, and did not hesitate to vent to the media. His outbursts often belittled management and sometimes teammates, creating distractions and disunity that led to stints with eight different teams. Writers described him as self-destructive, temperamental, mercurial, selfish, petulant, and duplicitous. Trouble seemed to follow him. He was arguably good enough to make the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but damaged his chances by using performance enhancing drugs (PEDs).

Gary Antonian Sheffield was born November 18, 1968, and grew up in the Belmont Heights section of Tampa, Florida. His father was Marvin Johnson.3 His stepfather and mother were Harold and Betty Jones. (Sheffield’s last name came from Lindsay Sheffield, the man Betty planned to marry after being abandoned by Johnson. However, before the wedding could be held, Sheffield was shot dead attempting to rob a nightclub.) Betty’s little brother was former New York Mets pitching star Dwight Gooden. Gary and his uncle Dwight grew up together and Gooden, four years older, always had the physical advantage. Exposed to Gooden’s blazing fastball, Sheffield developed quickly as a hitter. Their competition, Sheffield said, “ignited a fire in me that would never go out.”4

Sheffield’s Belmont Heights Little League team, which included future major leaguer Derek Bell, advanced to the finals of the 1980 Little League World Series, where it lost to Taiwan.5 The following year Sheffield was expelled from the team when, after being benched for skipping a practice, he chased his coach with a bat, finally having to be held back by teammates.6

Sheffield described himself as a product of his environment.7 It was rough and so was he. In eighth grade, he made a schoolmate pay him every day, otherwise he would thrash the kid. “There was no reason to do it,” Sheffield said. “I just did it because I felt I could.”8 In case fists weren’t enough, he sometimes brought a gun to school.9 When he and his friends went to another neighborhood, Sheffield said, “We’d have to fight our way out … The games we played almost always ended with blood.”10

With Gooden already tearing up the National League, Sheffield thought he would follow in his uncle’s footsteps as a pitcher. At 16, the right-handed Sheffield struck out 21 batters in one game.11 In 1986, his senior year at Hillsborough High School, his ERA was 1.81. But Sheffield was an even better hitter, batting .500 with 14 home runs and 31 RBIs in 22 games.12 Consequently, he was named the Gatorade National (High School) Player of the Year.13

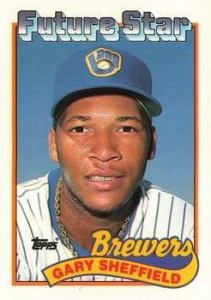

Sheffield hoped to play for the Braves, like his hero Hank Aaron.14 But in June, the Milwaukee Brewers chose Sheffield with the sixth overall pick of the amateur draft. Brewers vice president Al Goldis called Sheffield the best hitter he ever scouted.15

Seventeen years old and already the father of two, Sheffield was sent to the Brewers’ rookie-level team in Helena, Montana. He said the transition from his predominantly Black neighborhood to lily-white Helena made him feel as though he was “on the moon.”16 Nevertheless, he hit .365 with 15 homers and led the Pioneer League with 71 RBIs in 57 games.17

That December, Sheffield and Gooden were arrested after a late-night altercation with Tampa police. The police report stated that the two, driving separate cars, were pulled over for weaving recklessly. The encounter became physical and, while being handcuffed, Sheffield allegedly told the officer, “I’m going to kill you.”18 The ballplayers were charged with resisting arrest and battery of a police officer. Sheffield, by then an 18 year-old adult, pleaded no contest and was put on two years’ probation.19 He later claimed he and Gooden were targeted because they were driving fancy cars and that the charges were dropped.20

Sheffield excelled at all his minor-league stops. In 1987, he played the entire season with Single-A Stockton (California) and drove in 103 runs. He started the 1988 season at Double-A El Paso, hit .314 with 19 home runs in 77 games, and was named the Texas League’s Best Batting Prospect.21 Later that year, he advanced to Triple-A Denver, batted .344, cracked nine homers, and drove in 54 runs in 57 games.22 He was called up to the majors in September and started the Brewers’ final 23 games at shortstop.

As the 1989 season began, Sheffield was called the American League’s best prospect in 15 years and the favorite to win the Rookie of the Year Award.23 However, by mid-July, he was mired in a deep slump, led the Brewers in errors,24 and was sent back to Denver.25 While there, doctors discovered a broken bone in his foot.26 Sheffield had complained of discomfort since mid-May, but at the time it was diagnosed as a bone bruise.27 The misdiagnosis likely contributed to Sheffield’s poor performance and subsequent mistrust of the Milwaukee organization.

When Sheffield returned to the Brewers in September, he was displeased to find manager Tom Trebelhorn had installed Bill Spiers at shortstop and wanted Sheffield to play third base.28 “If they don’t need me to play shortstop, I’d rather go somewhere else,” Sheffield said. 29 Overall, he hit .247, with five homers and 32 RBIs in 95 games, and his predicted Rookie of the Year Award did not materialize.

Despite his complaints, the Brewers kept Sheffield at third base in 1990. On June 22, Sheffield’s .319 batting average led the Brewers, and he was on a 13-game hitting streak. But he still didn’t like playing third, and lobbied to return to shortstop, saying, “[Spiers is] a good player, but he’s not a Gary Sheffield-type player.”30 Trebelhorn’s response was, “Tough sh–.”31

Despite his complaints, the Brewers kept Sheffield at third base in 1990. On June 22, Sheffield’s .319 batting average led the Brewers, and he was on a 13-game hitting streak. But he still didn’t like playing third, and lobbied to return to shortstop, saying, “[Spiers is] a good player, but he’s not a Gary Sheffield-type player.”30 Trebelhorn’s response was, “Tough sh–.”31

Sheffield felt he was being mistreated, saying, “There was a lot of pressure put on me last season (1989). I felt some of it was because of racism.” He added, “Racism is everywhere. Some guys just hide it better than others.”32

Seeds of Sheffield’s perception of racism were sown by his grandfather, Dan Gooden, who told the five-year-old Sheffield about the hate mail Aaron received during his quest to break Babe Ruth’s career home run record. “Most white people are fine,” Gooden said, but others don’t want to see the record broken by a Black man. “They think the color of their skin entitles them to every honor [and] makes them superior.”33

Although Sheffield didn’t show much power, in 1990 he kept his batting average above .300 through late August before a slump reduced his final mark to .294 with an OPS34 of .771. An injured shoulder, which would plague his entire career, ended his season on September 12.

In early 1991, angry that Milwaukee had traded Dave Parker, Sheffield said, “[General Manager Harry Dalton] is ruining the team and will keep ruining it, because, as far as I’m concerned, he doesn’t know too much about [baseball].” Brewers coach Don Baylor, who doubled as Sheffield’s counselor, was asked if they had discussed the grievances and replied, “I’m sick of talking to him about complaints.”35

Sheffield’s season was a washout due to a jammed left shoulder and irritated wrist tendon.36 He played only 32 games after April 30, the last on July 24. A month later, he underwent surgery to relieve an impingement in the shoulder. His final batting average was .194 and his OPS, .597.

On March 26, 1992, the Brewers traded Sheffield to the San Diego Padres along with Geoff Kellogg for Ricky Bones, Matt Mieske, and José Valentín. Afterward, Sheffield smiled and said, “It’s a load off my back. It’s what I’ve been wanting for … a long time.”37 He added, “The Brewers brought out the hate in me … I was a crazy man. I hated Dalton so much I wanted to hurt the man.” 38

He also admitted, “If the official scorer gave me an error, I didn’t think was an error, I’d say, ‘OK here’s a real error,’ and I’d throw the ball into the stands on purpose.” Sheffield asserted that Milwaukee’s management never wanted him to be the face of their franchise. “If I was white …,” Sheffield said, “I would have been the All-American guy.” 39

In San Diego, Sheffield was given a clean slate by Padres’ manager Greg Riddoch. After watching him play for two months, Riddoch said, “He’s been a godsend, an absolute gift from above.” 40

Indeed. Sheffield was named The Sporting News’s Player of the Year and nearly won the Triple Crown,41 leading the National League with a career-high batting average of .330 and finishing third in home runs (just two off the lead) and fifth in RBIs (just nine back). Sheffield also won The Sporting News’s National League Comeback Player of the Year Award and, for the first time, made the All-Star Team and won a Silver Slugger Award.

But after Sheffield’s great year, the Padres feared they would not be able to afford him when his contract expired at the end of the following season. Not wanting to lose him in free agency, they traded Sheffield and Rich Rodriguez to the Florida Marlins for two minor leaguers and future Hall of Famer Trevor Hoffman on June 24, 1993.

Although Sheffield had an above-average season, all his offensive statistics declined from 1992. Nevertheless, unlike the Padres, the Marlins were not afraid to give him a huge payday. In late September, they signed him to a four-year, $22.45 million contract, making him the highest-paid third baseman in baseball.

On December 5, 1993, around 3 a.m., Sheffield was arrested for driving 110 mph under the influence. He apologized to Marlins’ manager Rene Lachemann and General Manager Dave Dombrowski and began counseling with the team psychologist.42

After Sheffield led major-league third basemen with 34 errors in 1993,43 the Marlins moved him to right field in 1994. Except for a handful of games, he remained a corner outfielder the rest of his career. Despite playing only 87 games in ’94 due to his troublesome left shoulder and the players’ strike that shortened the season, Sheffield drove in 78 runs, a pace of 145 in 162 games.

The following year, Sheffield was again hampered by injury. On June 10, 1995, he tore a ligament in his left thumb. It was thought he would be out for the season.44 But he gamely returned and hit .343 with 10 homers and 27 RBIs in September. Although he played just 63 games overall, he excelled, batting .324 with a 1.054 OPS.

Between the early parts of 1995 and 1996, Sheffield was beset by a series of disturbing events. First, he was told a former girlfriend was plotting to kill his mother.45 Then, he was pulled off the team plane by sheriff’s deputies after they received a tip that he was carrying illegal drugs.46 Next, while stopped at a red light in Tampa, an unknown man fired a shot at Sheffield which grazed his shoulder. 47 Last, he was slapped with a restraining order after the mother of one of his children (before marrying, he had four, with four women) received a threatening phone call from a man claiming to be Sheffield. On her driveway, she found a menacing note with two bullets on top.48

Sheffield was never shown to be at fault in any of those incidents, and no drugs were found on him on the team plane. Even so, the Marlins brought in Major League Baseball security to investigate and had Sheffield undergo a psychiatric evaluation. 49 Shortly thereafter, he hired a public relations firm to help transform his image.50

Sheffield gave generously to the Miami community. He sponsored Sheff’s Kitchen, a program that provided free tickets to all Marlins home games and autographs for 25 underprivileged kids.51 He also donated $200 for every home run and $100 for every double and triple to the Florida RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) program. Most philanthropic of all, he paid $100,000 for a man’s liver transplant.52

Sheffield started the 1996 season by tying the then-major-league record53 with 11 home runs in April54 and continued his hot hitting throughout the summer. Injury-free, he played a career-high 161 games, and led the NL in OBP (on-base percentage55) (.465), OPS (1.090), and OPS+56 (189) – all of which would remain career highs.57 His 42 homers ranked second, and – exemplifying the fear that Sheffield struck in opposing pitchers – he was walked 142 times (19 intentional), the second-most in the major leagues in the 27 seasons since 1969.58

However, after Dombrowski told him he would be traded if ownership decided to play younger players, on August 16 Sheffield let loose with what was described as his “longest and most vicious tirade of the season.” He called Dombrowski a liar and criticized his ability, saying, “This team is not set up to [win the division],” a statement denouncing not only the GM, but also Sheffield’s own teammates. Dombrowski said, “I knew he wouldn’t be happy [if the youth movement happened], because I understand he wants to be with a winner. I didn’t say we were going to trade him. I said if … I felt like I was doing him a favor [by letting him know].”59

But rather than go with young players in 1997, the Marlins did the opposite. In an effort to boost declining attendance, Miami committed nearly $100 million to six free agents including Alex Fernandez, Moisés Alou, and Bobby Bonilla. 60 They even added two-time Manager of the Year, Jim Leyland.

Through June 1, Sheffield’s slugging percentage was just .386, but from then until the end of the season, he slugged .471 with an .889 OPS, not as impressive as usual, but enough to give the Marlins a boost. The team finished with the NL’s second-best record, 92-70, and earned a wild-card playoff spot.

The Marlins swept San Francisco in the Division Series, and defeated Atlanta in the NLCS, four games to two. Against Cleveland, Florida won the World Series on Edgar Renteria’s two-out single in the 11th inning of the seventh game. In Game Three, Sheffield led the Marlins to a 14-11 victory, as he went 3-for-5 with a double, homer, and five RBIs, and robbed Jim Thome of an extra-base hit with a leaping catch at the wall to preserve a seventh-inning tie. Sheffield’s cumulative postseason slash line was .321/.521/.540/1.061,61 with 20 walks in 71 plate appearances.

Although the Marlins’ attendance increased by about 35 percent in 1997, to 2.4 million fans, the team still failed to turn a profit. With ownership claiming to need to cut salary by more than half, the franchise broke up its championship roster, trading most of its top players. On April 19, 1998, Sheffield, still with the team, told ESPN he felt betrayed, was having a hard time staying motivated, and was embarrassed by the Marlins’ poor performance.62 It was apparently the last straw for Marlins’ brass.

On May 14, Sheffield was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers, along with Manuel Barrios, Jim Eisenreich, Bonilla, and Charles Johnson for future Hall of Famer Mike Piazza and Todd Zeile. To coax Sheffield to waive his no-trade clause, the Dodgers paid him $5 million.63

Sheffield was voted to the All-Star team but said he would skip the game because he missed his family in Florida. “My kids have been … calling me all the time,” he said. “It’s making me homesick, and I need to see their faces.”64 Fearing the organization would look bad if Sheffield didn’t show up, the Dodgers reportedly paid for his family to attend.65

On June 28, Sheffield fought with Pirates catcher Jason Kendall when Kendall thought Sheffield had maliciously knocked his helmet off during a play at the plate. Sheffield said the contact was unintentional. Both players were ejected and later suspended for three games.66

Though Sheffield’s home run and RBI totals were not gaudy, he exceeded the benchmarks of .300 BA (.302), .400 OBA (.428), and .500 SLG (.524), an achievement indicating all-around excellent batting performance. In his career, he accomplished this triad seven times.

Though Sheffield’s home run and RBI totals were not gaudy, he exceeded the benchmarks of .300 BA (.302), .400 OBA (.428), and .500 SLG (.524), an achievement indicating all-around excellent batting performance. In his career, he accomplished this triad seven times.

In 1999, Sheffield became the first L.A. Dodger to exceed a .300 batting average with at least 30 homers, and 100 walks, RBIs, and runs scored in a season.67 The only Brooklyn Dodger to do it was Duke Snider in 1955.

When Sheffield duplicated the feat in 2000, his career-high 43 homers tied Snider’s 1956 franchise record.68 Sheffield finished second in the NL with a 176 OPS+ and ninth in MVP voting.

On February 5, 2000, Sheffield married gospel singer DeLeon Richards, who had been the youngest person ever nominated for a Grammy,69 for an album she recorded when she was just seven years old.70 As of 2023, the couple remained married and had three children together.71

In February 2001, the Dodgers said Sheffield demanded to be traded or given a lifetime contract extension. Sheffield denied it, called the team’s brass “liars,” and said club chairman Bob Daly bungled the situation and had “set out to bury” Sheffield.”72 Sheffield threatened to boycott spring training and implied that – if forced to play for the Dodgers – he would give less than full effort. “If they keep me, I will play,” he said, “but I don’t want to hit one more home run for the Dodgers.” 73

Sheffield played, and hit home runs, 36 of them, but he remained irritated because he believed the Dodgers had given bigger contracts to less-worthy players. The focus of his animosity was Shawn Green, who made $2 million more annually. He fumed when Green broke his single-season Dodgers home run record, grumbled when he batted behind Green in the lineup, and the two nearly came to blows when Sheffield thought Green didn’t try hard enough to score on a hit that would have gotten Sheffield closer to his 100th RBI.74

On New Year’s Day 2002, Sheffield said, “I don’t want to be with an organization that constantly tells me one thing and then does another.”75 Nor did the Dodgers want to endure another season of turmoil. On January 15, L.A. accommodated Sheffield by trading him to the Atlanta Braves for Brian Jordan, Odalis Pérez, and Andrew Brown.

After the trade, former teammate Paul Lo Duca revealed that Sheffield’s feud with management had caused internal trouble. Lo Duca said, “It set a tone for the entire season, and I think a lot of guys walked lightly around Gary. That’s something you don’t want in a clubhouse.”76 Nevertheless, through 2022, Sheffield held Dodgers career records for OBP (.424), slugging (.573), and OPS (.998).77

During the 2001-2002 offseason, Sheffield spent two months at Barry Bonds’s home, where the two worked out daily.78 Fresh off his record-setting, 73-homer season, Bonds introduced Sheffield to his new diet and training regimens. 79

Although Sheffield’s homer and RBI totals declined in 2002 because he missed games due to injuries, his batting average and OPS were typically excellent. The Braves moved into first place in the NL East on May 28 and never left, building a 19½ game lead by August 15 and winning the most games in the NL. Despite that, they lost to the San Francisco Giants in the first round of the playoffs. Sheffield went 1-for-16 but drew seven walks and hit a home run.

In 2003 Sheffield, age 34, had his best season. He attained career highs in runs, hits, doubles, RBIs, and total bases, batted over .300 for the sixth year in a row, and his OBP exceeded .400 for the ninth consecutive season. He finished third in NL MVP voting, made his seventh All-Star team, and won his third Silver Slugger Award.

The Braves again won the NL East in a runaway (their ninth straight NL East title) and again won the most games in the National League. But again, they lost in the NLDS, this time to the Chicago Cubs. Sheffield contributed just two singles and one RBI in 14 at bats.

An investigation into the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) – a company suspected of selling illegal steroids to athletes – had begun that summer. Sheffield’s name appeared in BALCO’s records, and in December, he and Bonds were called to testify before a grand jury.

Afterward, Sheffield denied taking PEDs, saying he hadn’t put on a pound since he was a rookie.80 “Anybody that wants to say I (should) take the challenge of taking a test,” Sheffield said, “I’ll be the first guy up there and I won’t back down.”81 However, when Newsday reporter Jon Heyman set up a drug test, Sheffield did back down, saying, “Talk to the Players Association.”82

In October 2003, Sheffield admitted he used a BALCO-supplied topical ointment (known as “the cream”) to heal scars on his leg and was shocked to find out it was a testosterone-based steroid. 83 But Sheffield’s name appeared on a drug calendar kept by BALCO trainer Greg Anderson, which suggested Sheffield used not only the cream, but also human growth hormone and injectable testosterone.84

The cost-cutting Braves, coming off an eighth consecutive playoff failure, offered free agent Sheffield $10 million for 2004, a decrease from his $11.4 million salary the previous year.85 Instead, negotiating without an agent, Sheffield got a better deal from the New York Yankees, a reported $39 million over three years, despite the BALCO reports.

Over Sheffield’s 12 NL seasons (1992-2003), he produced the league’s second-highest OPS+ (156), trailing Bonds’ 200, but better than future Hall-of-Famers Jeff Bagwell, Larry Walker, Chipper Jones, and Piazza.

Despite a shoulder injury that caused “unbearable” 86 pain and later required surgery, Sheffield was terrific in 2004. He hit 36 home runs, led the Yankees in RBIs (121), runs scored (117), and OPS+ (141), and finished second to Vladimir Guerrero in American League MVP voting.

New York won the most games in the AL and defeated the Minnesota Twins in the Division Series. But the Yankees famously lost the ALCS to the Red Sox after leading three games to none. Sheffield batted .333 with a homer and seven walks in that series, but after a torrid 9-for-13 with five RBIs in the Yankees’ three wins, he (along with several teammates) disappeared in the four subsequent losses, a single his only hit in 17 at-bats.

Sheffield turned in another fine year in 2005, producing batting statistics remarkably similar to 2004. For the third consecutive season – and final time in his career – he exceeded 30 home runs and 120 RBIs, finished in the top eight in MVP voting, made the All-Star team, and won a Silver Slugger Award.

A midsummer magazine article quoted Sheffield as saying, “I know who the leader is on the team. I know who the opposing team comes in knowing they have to defend to stop the Yankees. The [fans] don’t know. Why? The media don’t want them to know. They want to promote two players in a positive light, and everyone else is garbage.”87 It was widely assumed the two players were Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez. Initially, Sheffield claimed the writer “lied.”88 Later he recanted saying, “If that’s what I said, that’s what I said.”89

In 2006, Sheffield had a great start, batting .341 with 18 RBIs in the first 22 games. But he injured his left wrist, underwent surgery, and appeared in just 39 contests. 90 The Yankees led the AL with 97 victories, and won the first game of the ALDS against the Tigers. But Detroit swept the next three, eliminating New York in the first round of the playoffs for the second consecutive season — following being knocked out in five games by the Angels of Anaheim in 2005. Sheffield returned to action for the playoffs but mustered just a single in 12 at bats.

That off-season, the Yankees sought to trade Sheffield against his wishes. As he had before, he tried to sabotage the effort, announcing that any team trading for him would be getting an unhappy player. The ploy did not work, and he was dealt to the Tigers for minor-leaguers Anthony Claggett, Humberto Sánchez, and Kevin Whelan. Sheffield later said he was glad to rejoin former Marlins colleagues Leyland and Dombrowski in Detroit.91

Sheffield remained an above-average offensive player (cumulative 109 OPS+) his final three seasons, two with the Tigers and his last, with the Mets, with whom he hit his 500th career homer on April 17, 2009.

Sheffield was a unique player, one of just seven to amass at least 500 home runs, 1,500 runs scored, 1,500 RBIs, and 200 stolen bases.92 A good contact hitter who rarely swung at pitches outside the strike zone, he also walked more than he struck out. Only three players in baseball history meet each of the five preceding criteria: Sheffield, Bonds, and Aaron.

Setting aside his link to PEDs, Sheffield’s career totals justify him as a serious candidate for the Hall of Fame. As of 2023, his career totals in home runs, RBIs, runs scored, and walks all ranked in the top 40 all-time. His 140 OPS+ was better than Hall-of-Fame right fielders Al Kaline (134) and Roberto Clemente (130). But, unlike them, Sheffield was a defensive liability. In 15 of the 16 seasons in which he played at least 50 games, advanced statistics rated him a below-average fielder.93 However, even after taking defense into account – as wins above replacement (WAR)94 does – Sheffield compares favorably. Of the 28 right fielders in the Hall, Sheffield’s 61 WAR ranked 15th, smack in the middle, behind Dave Winfield (64) and ahead of Guerrero (60).95

After retiring, Sheffield returned to Tampa and worked as an agent for baseball players. From 2013 through 2020, Sheffield was a studio analyst for TBS. After retiring from the role, he admitted he no longer watched baseball, and stated that while at TBS, “I never watched the games during the season. I would get educated on it when I got there.”96

Sheffield received between 11 and 14 percent of votes in his first five years on the Hall of Fame ballot. He jumped to 31 percent in 2020, 41 percent in 2021 and 2022, and 55 percent in 2023, still short of the 75 percent required for induction. The 2024 ballot will be his 10th and final chance to be voted in by the baseball writers, although the various veterans committees could later vote him in.

In an interview in January 2023, Sheffield stated he believed he should be elected to Cooperstown, saying: “I grew up in an era where they say there are the benchmarks, once you hit the benchmarks [like 500 home runs] that’s … it. All the things people want to put into play … It’s good to get all the facts straight and if you get the facts straight, you’ll see a lot of things you’re saying [about alleged steroid use] are not true. There’s always hope.”97

Last revised: August 9, 2023

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Steve Ferenchick.

Photo credits: Trading Card DB.

Sources

In addition to sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted www.baseball-reference.com.

Notes

1 Bob Nightengale, “A Dugout from Hell,” Los Angeles Times, June 9, 1992: C4.

2 Michelle Genz, “Gary Sheffield: The Bat Man,” Miami Herald, June 1, 1997: 9A.

3 Gary Sheffield and David Ritz, Inside Power, (New York, New York: Crown Publishers, 2007), 154.

4 Gary Sheffield, “Where I’m Coming From,” The Players’ Tribune, July 15, 2016. https://www.theplayerstribune.com/articles/gary-sheffield-where-im-coming-from

5 Chris De Luca, “Hard Knocks,” Times-Advocate (Escondido, California), March 21, 1993: C1.

6 Sheffield, “Where I’m Coming From.”

7 Sheffield, “Where I’m Coming From.”

8 De Luca, “Hard Knocks.”

9 Scott Tolley, “Trouble Plagues Marlins Star,” Palm Beach Post, March 24, 1996: 1A.

10 Sheffield, “Where I’m Coming From.”

11 “Notes & Quotes,” Tampa Bay Times, September 2, 1984: 4C.

12 Bob Nightengale, “No More Trouble Brewing,” Los Angeles Times, March 29, 1992: C3.

13 https://playeroftheyear.gatorade.com/winner/gary-sheffield/20847.

14 Sheffield, Inside Power, 43.

15 Nightengale, “No More Trouble Brewing.”

16 Sheffield, Inside Power, 59.

17 Sheffield, Inside Power, 154.

18 Joey Johnston, “Tampa Police Arrest Mets Pitcher Gooden,” Tampa Tribune, December 15, 1986: 1A.

19 Nightengale, “A Dugout from Hell.”

20 Sheffield, Inside Power, 52.

21 1989 Score Gary Sheffield Rookie Card #625.

22 1989 Fleer #196 Gary Sheffield Baseball Card.

23 Andy Baggot, “Unhappy Sheffield Unloads,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), May 27, 1989: 1B.

24 Staff, “Sheffield Fires at Brewers,” Wisconsin State Journal, July 18, 1989: 1D.

25 AP, “Sour Notes Spoil Sheffield’s Tune,” La Crosse Tribune (La Crosse, Wisconsin), July 16, 1989: B-1.

26 AP, “Sheffield Returns as Third Baseman; Molitor at Second,” Capital Times, July 18, 1989: 16.

27 Andy Baggot, “Sheffield Break May Be Old One,” Wisconsin State Journal, September 16, 1989: 3B.

28 AP, “Sheffield Questions Future,” Chippewa Herald-Telegram (Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin), September 20, 1989: 1B.

29 Andy Baggot, “Take My Advice,” Wisconsin State Journal, September 20, 1989: 1B.

30 Andy Baggot, “Sheffield Erupts Again,” Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), July 20, 1990: 1C.

31 Gregg Hoffmann, “Sheffield Checks Out in Confusion,” Kenosha News, September 27, 1990: 21.

32 Gregg Hoffmann, “Baylor Helped Sheffield Adjust,” Kenosha News, July 29, 1990: D5.

33 Sheffield, Inside Power, 16.

34 OPS is short for On-base percentage Plus Slugging percentage (OBP+SLG). It has become popular because it correlates well with team runs scored and is easy to calculate. https://www.eg.bucknell.edu/~bvollmay/baseball/runs1.html

35 Gregg Hoffmann, “Sheffield Stirs Resentment,” Kenosha News, April 6, 1991: 19.

36 Andy Baggot, “Sheffield Tries to Hit, Encounters Pain in Arm,” Wisconsin State Journal, May 26, 1991: 6E.

37 AP, “Brewers Roll the Bones, Trade Sheffield,” Sheboygan Press, March 28, 1992: 11.

38 Nightengale, “A Dugout from Hell.”

39 Nightengale, “A Dugout from Hell.”

40 Nightengale, “A Dugout from Hell.”

41 Bob Nightengale, “Sheffield Honored by TSN,” Los Angeles Times, October 24, 1992: C2.

42 Amy Niedzielka, “Sheffield Apologizes, Seeks Help,” Miami Herald, December 9, 1993: 2D.

43 Amy Niedzielka, “Money Can’t Buy Gary Glove,” Miami Herald, October 1, 1993: 1D.

44 Dave Sheinin, “Sheffield Out for Season,” Miami Herald, June 12, 1995: 6D.

45 Ken Rodriguez, “Sheffield’s Ex-Girlfriend: Plot on his Mom ‘A Hoax’,” Miami Herald, February 19, 1995: 11C.

46 Gordon Edes, “FBI, League Investigating Sheffield Incident,” News Press (Fort Myers, Florida), January 8, 1996: 6B.

47 Bill Chastain, “Sheffield Thankful to Be Alive,” Tampa Tribune, November 1, 1995: Sports-3.

48 Edes, “FBI, League Investigating Sheffield Incident.”

49 Tolley, “Trouble Plagues Marlins Star.”

50 Gordon Edes, “Sheff Concocts Image Makeover,” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), April 4, 1996: 1C.

51 Evan Grant, “Shades of Sheffield,” Florida Today (Cocoa, Florida), March 12, 1996: 1C.

52 Mike Phillips, “Bright Future, Troubled Past,” Miami Herald, April 30, 1995: 12B.

53 The record of 11 in April previously held by Sheffield and Mike Schmidt (1976) has since been shattered and stands at 14 as of 2023, held by Albert Pujols (2006), Alex Rodriguez (2007), Cody Bellinger (2019) and Christian Yelich (also 2019).

54 Phillips, “Bright Future, Troubled Past.”

55 Also known as on-base average. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/On-base_percentage

56 OPS+ is defined by baseball-reference.com as 100*(OBP/league OBP + SLG/league SLG -1) adjusted to the player’s ballpark. It is NOT 100 times the ratio of a player’s OPS to league OPS (100*OPS/league OPS). OPS+ is a more meaningful statistic than OPS because it correlates well to run production for players with a similar number of plate appearances and it shows how much the player is above-average (an OPS+ of 150 is 50 percent above average). It also penalizes the player whose home park helps run scoring, and vice versa. For example, this is why Larry Walker’s career OBP and SLG (.400 and .565) are both higher than Sheffield’s (.393 and .514), yet Walker (who played nine seasons at Coors Field) and Sheffield have nearly the same career OPS+ (Walker, 141 and Sheffield, 140).

57 For seasons in which he qualified for the batting title.

58 Bonds walked 151 times, also in 1996.

59 Mike Phillips, “Sheffield Tirade Rips Dombrowski,” Miami Herald, August 17, 1996: 12C.

60 AP, “Sheffield Gets Biggest Bucks,” Tampa Bay Times, April 3, 1997: 5C.

61 A batter’s slash line gives batting average (BA)/on-base percentage (OBP)/slugging percentage (SLG)/ and sometimes OPS (OBP+SLG).

62 David O’Brien, “Sheffield Stands by Betrayal Statements,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, April 19, 1998: 10C.

63 Jason Reid, “Sheffield Is Officially on the Block,” Los Angeles Times, February 19, 2001: D1.

64 Staff, “Sheffield Recants, Accepts His All-Star Assignment,” Los Angeles Times, July 2, 1998: C8.

65 Ross Newhan, “Dodgers Need to Find Answers,” Los Angeles Times, March 15, 1999: B1.

66 Jim Hodges, “After Brawl, Dodgers Not So Sure What Hit Them,” Los Angeles Times, June 29, 1998: C1.

67 Jason Reid, “Sheffield Discovers a New Motivation,” Los Angeles Times, February 25, 2000: D14.

68 Sheffield’s share of the team record lasted just one year, as Shawn Green set a new record (still standing through 2022) with 49 home runs in 2001.

69 https://www.grammy.com/artists/deleon-richards/13725.

70 Susan Taylor-Martin, “No More Trouble Brewing,” Tampa Bay Times, December 7, 2017: C3.

71 Sheffield, Inside Power, 221.

72 Jason Reid, “Sheffield Says Daly Is One to Blame,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 2001: D1.

73 Reid, “Sheffield Says Daly Is One to Blame.”

74 Bill Plaschke, “Last Word Belongs to Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, January 16, 2002: D1.

75 Jason Reid, “Sheffield Claims Dodgers, Evans Have Misled Him,” Los Angeles Times, January 2, 2002: D1.

76 Thomas Stinson, “Sheffield’s Best Might Be Ahead,” Atlanta Constitution, March 31, 2002: P1.

77 Among Dodgers with 2,000 or more plate appearances.

78 Tim Tucker, “Bonds Helps Sheffield Keep His Eye on the Prize,” Atlanta Constitution, April 7, 2002: E2.

79 Stinson, “Sheffield’s Best Might Be Ahead.”

80 Thomas Stinson, “High Profile,” Atlanta Constitution, March 9, 2004: C1.

81 Sam Borden, “Ready for Tests and Any Challenge,” Daily News, February 20, 2003: 85.

82 Mike Penner, “Steroid Use is Putting Pro Leagues to the Test,” Los Angeles Times, March 3, 2004: D2.

83 Ken Davidoff, “Sheff’s Bombshell,” Newsday (New York, New York), October 5, 2004: 72

84 Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams, Game of Shadows, (New York, New York: Gotham Books, 2006), 130,131.

85 Stinson, “High Profile.”

86 Jim Baumbach, “Sheffield Gets Good News on Aching Shoulder,” Newsday, August 19, 2004: 74.

87 Stephen Rodrick, “Gary Sheffield is the Yankees’ MVP,” New York Magazine, August 3, 2005.

https://nymag.com/nymetro/news/sports/features/12398/

88 Sam Borden, “Sheffield Claims Mag Writer ‘Lied’,” Daily News, August 6, 2005: 47.

89 Wallace Matthews, “When Sheff Stirs Pot, Anger Bubbles Over,” Newsday, August 10, 2005: 74.

90 Anthony Rieber, “Slumping Rodriguez Hears Jeers,” Newsday, June 14, 2006: 61.

91 Sheffield, Inside Power, 225.

92 The other 6 players in baseball history through 2022 with such numbers are Hank Aaron, Barry Bonds, Reggie Jackson, Willie Mays, Frank Robinson and Alex Rodriguez.

93 https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sheffga01.shtml (Standard Defense Table, Rtot column).

94 WAR measures a player’s value in all facets of the game by deciphering how many more wins he’s worth than a player just good enough to play in the majors. Piper Slowinski, “What Is WAR,” February 15, 2010.

https://library.fangraphs.com/misc/war/

95 Three right fielders, Dwight Evans (67), Reggie Smith (65), and Shoeless Joe Jackson accumulated more WAR than Sheffield, but are not yet enshrined.

96 Kyle Koster, “Is It Too Much to Ask That Studio Analysts Watch the Sport They’re Analyzing?”, The Big Lead, April 22, 2021. https://www.thebiglead.com/posts/gary-sheffield-tbs-didnt-watch-baseball-01f3x47b59yb

97 Tom D’Angelo, “Gary Sheffield says he belongs in Baseball Hall of Fame: ‘It’s good to get all the facts straight’,” Palm Beach Post, January 31, 2023. https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/mlb/2023/01/31/gary-sheffield-derek-jeter-speak-out-hall-fame-voting-process/11155312002/

Full Name

Gary Antonian Sheffield

Born

November 18, 1968 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.