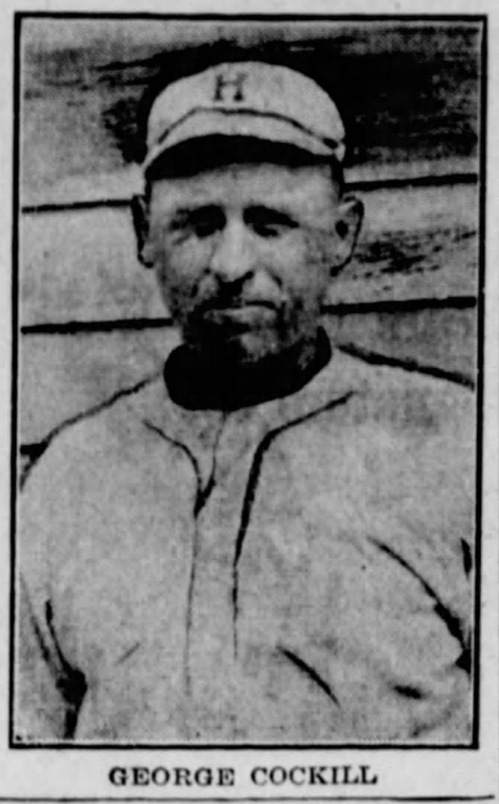

George Cockill

In the history of Bucknell University athletics, George Cockill’s name looms large. A three-sport varsity athlete in football, basketball, and baseball at the college in central Pennsylvania, the Class of 1905 alumnus returned to serve as varsity head coach in all three sports. He was posthumously selected to the school’s athletic Hall of Fame.1

In the history of Bucknell University athletics, George Cockill’s name looms large. A three-sport varsity athlete in football, basketball, and baseball at the college in central Pennsylvania, the Class of 1905 alumnus returned to serve as varsity head coach in all three sports. He was posthumously selected to the school’s athletic Hall of Fame.1

Cockill’s contribution to major-league baseball was much more modest. A successful minor-league first baseman and manager, Cockill spent one season, 1915, as a substitute umpire in the National League. He worked 61 games, all on the basepaths, mostly as the partner of future Hall of Famer Bill Klem. After that brief stint, Cockill went back to his home state of Pennsylvania, taking a baseball-adjacent position with industrial giant Bethlehem Steel and getting involved in local government.

George Washington Cockill2 was born on June 28, 1881, in Pottsville, Pennsylvania, the son of Thomas and Catherine “Kate” (Cooper) Cockill. Thomas Cockill worked as a foreman at a coal mine, and as a carpenter boss for the Philadelphia & Reading Coal & Iron Company.3 Kate Cockill died in 1902, and her husband subsequently remarried.4 Family records on Familysearch.org indicate that the Cockills had five children, and Thomas Cockill’s obituary in 1931 reported that he was survived by three daughters and two sons.5

Tom Cockill, also known as “Joe,” might have passed on some baseball talent to his son. In April 1901, employees of the Philadelphia & Reading company uncovered a layer of undisturbed snow while working and broke ranks for a snowball fight. “Joe Cockill makes a particularly hard snow ball and has a good throwing arm, the boys all agree,” a news story summarized.6

George began his journey to broader fame at the Keystone State Normal School in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, the predecessor to today’s Kutztown University. At the time, it was chiefly a teachers’ college.7 He served as president of the school’s literary society and graduated in 1901 with the unofficial title of “class optimist.”8 He excelled athletically, reeling off 80-yard runs on the football gridiron and striking out 14 hitters as a starting pitcher on the baseball field.9 Years later, when he was coaching at Bucknell, a Kutztown newspaper proudly noted that Cockill had “obtained considerable of his athletic training” at the local school.10

Cockill’s first exposure to pro baseball came in the summer of 1901, when he pitched with varied results for the Pottsville team in the Class D Pennsylvania State League.11 In one notable game, he pitched a complete-game five-hitter to beat a team from Olyphant, Pennsylvania, 2-1.12

From Kutztown Cockill moved on to Bucknell, which had recently sent future Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson to the pro baseball ranks.13 Cockill served as class vice president during his sophomore year, also serving on his class’s Executive Committee and on the Junior Prom Committee and joining two fraternities.14 But he made his greatest impact in athletics, where he won four varsity letters in football, three letters in basketball, and four in baseball, serving as captain of all three teams.15 Cockill began as a center fielder at Bucknell, then switched to first base.16 His height and weight were listed as 5-feet-9 and 175 pounds.17

Cockill was accused by Sporting Life magazine in March 1906 of having played two seasons in the independent Tri-State League under an assumed name, Potts – perhaps a reference to his birthplace of Pottsville.18 A Pennsylvania news story from July 1904 suggests there might have been truth behind the charge. The story mentions that a “Potts” on a Shamokin, Pennsylvania, team made a key error, but there is no Potts in the box score – only Cockill, credited with playing first base and making one of his team’s three errors.19

After graduation in 1905, Cockill ventured back into pro baseball as manager and first baseman of the Shamokin team in the independent Susquehanna League.20 The loop was a disorganized affair. In May it dissolved and then reorganized; in early July, team representatives quibbled over when the season officially opened or would open, with July 5 being chosen as a date.21 The league collapsed in early August.22 Through the chaos, Cockill established his talent. In August, a Scranton, Pennsylvania, newspaper urged the local nine to poach Cockill from Shamokin: “Cockill of the Shamokin team is the man the players want to see signed. He is better than any first baseman in this league according to those who have seen him play.”23

Beginning in his age-25 season, Cockill finally got his pro career on solid footing with three seasons at the Class B level – at the time two levels below the majors. He spent the 1906 and ’07 seasons with Albany of the New York State League and 1908 with Williamsport of the Tri-State League, hitting above .290 in the latter two seasons.

Near the end of July 1907, the Detroit Tigers purchased his rights for $2,500, effective the following season.24 Cockill hit .429 for the defending AL champion Tigers in spring training of 1908, but incumbent first baseman Claude Rossman hit .351 and kept his job.25 Manager Joe Cantillon of the Washington Nationals reportedly asked about Cockill that June, but the Tigers, not interested in helping an AL rival, wouldn’t let him go.26

Cockill, newly married to the former Mary Higgins, announced his retirement after the 1908 season to work full-time for a steel company, but returned to baseball the following spring.27 Cockill spent 1909 and 1910 with Montreal of the Class A Eastern League, one step below the majors. He didn’t seize the opportunity to show his skills at this higher level, as his batting average slumped to .247 in 1909 and .201 in 1910. This appears to be where his momentum to reach the majors as a player faltered.

The events that brought him to the bigs as an umpire were only just beginning, though. Retreating to Class B, Cockill purchased a share of the Reading (Pennsylvania) Pretzels of the Tri-State League, hitting .360 as their first baseman and co-manager with partner Bill Coughlin. He also fielded at a .995 clip as the Pretzels won the league title.28

His stock again on the rise, Cockill signed on in 1912 as player-manager of the Tri-State League’s Harrisburg Senators, selling his share of the Reading team.29 He stayed there for three seasons and became something of a local hero, hitting .286, .287, and .313 in regular duty and guiding the team to league championships in 1912 and 1914.30 “Cockill is the Connie Mack of the Tri-State League,” one Harrisburg newspaper summarized.31

During his run of success in Harrisburg, Cockill on several occasions met John Tener, a former major-league pitcher who served concurrently as governor of Pennsylvania and NL president.32 In January 1915 Tener appointed Cockill an NL umpire even though Cockill had no recorded experience as a professional arbiter.33 It appears that Cockill’s reputation as the proverbial “good baseball man” – experienced, trustworthy, and successful as a player, manager, and co-owner – outweighed his lack of direct experience. “Cockill is a level-headed, up-standing, courageous baseball man and it is the belief of his friends that he will make good in the trying place to which he has been assigned,” the Harrisburg Telegraph editorialized.34

Cockill had another qualification for an NL job: He’d avoided the Federal League, whose emergence as an outlaw third major league in 1914 had doubtless tempted other minor-league lifers. Cockill was reportedly offered the job of managing the FL’s Baltimore Terrapins before the 1914 season but was passed over after demanding a guarantee of three years’ salary.35 (His pay for his first season as an umpire was reported as $2,400, equivalent to more than $76,000 in 2024.36)

Some news accounts described Cockill’s role as a regular umpiring job. But others described him as a substitute ump, with some noting that he was replacing Fred Lincoln, a sub who’d worked just 31 games in his only season in the majors.37 Tener assigned Cockill to begin the season on unspecified “special duty.” The new hire did not make his big-league debut until May 29, umpiring alongside Klem at a Philadelphia Phillies-Boston Braves game at Fenway Park.38

From a historical viewpoint, Cockill’s stint in the majors was quiet. He did not umpire any no-hitters or cycles and was not chosen to work the World Series. He made no ejections. News accounts tended to speak of him positively, although one Philadelphia newspaper tut-tutted him in August for making calls too quickly.39 In addition to Klem, he also partnered with Cy Rigler and Hank O’Day.

Cockill’s game record indicates that he did not work during a stretch of late June and early July and was absent from the majors throughout September, although he called a Chicago White Sox-Pittsburgh Pirates exhibition game on September 9 in Pittsburgh.40 The author of this biography found no indication that Cockill was either injured or out of favor during these periods. It seems most likely that he was hired as a substitute, and the NL simply didn’t need him.

After his September layoff, the league called Cockill to Boston in early October to work the final few days of the season.41 Cockill’s most interesting game in the majors might have been his last, a faceoff between the New York Giants and Boston Braves at Braves Field on the season’s final day, October 7. The teams combined for 41 hits and 23 runs yet finished the nine-inning slugfest in just 62 minutes. The Giants won, 15-8. The Boston Globe described the game as a “burlesque,” with both pitchers lobbing the ball to the plate, and noted that neither Braves manager George Stallings nor New York’s John McGraw appeared to be present.42

The fact that Cockill never umpired behind the plate was consistent with some other NL umpires’ experience. Four umps – Klem, Rigler, Lord Byron, and Ernie Quigley – handled the lion’s share of the work behind the plate, and other arbiters got few or no opportunities there.43 Bob Emslie worked 145 games in 1915 without a plate assignment, while Bill Hart drew one in 99 games.44

Hart quit the league in early August, and Cockill was rumored as a replacement for his full-time position.45 But Cockill apparently decided that he preferred managing the on-field action to impartially judging it. In January 1916 he announced that he had given up umpiring and hoped to return to Harrisburg as the manager of a new team in the Class B New York State League.46

In June of that year, Cockill overcame resistance from the league’s president and arranged for the Troy, New York, franchise to move to Harrisburg in midseason. Cockill served as manager and main financial backer, though he hoped to sell stock to local investors after the team arrived.47 By the end of July, a parade was being planned to celebrate Cockill, partner Walter Blair, and the city’s new team.48

The success didn’t last. Cockill failed to secure outside investment, and by early June 1917, he made clear that he would fold the team without additional support.49 It didn’t come, and the team went under.50 This lack of support was not unique to Cockill’s operation – all teams in the league lost money in a season described as “disastrous.”51 The loop did not return for 1918.

This marked the end of Cockill’s involvement with professional baseball, but his work provided him with a different kind of diamond opportunity. In mid-1917 he was hired by Bethlehem Steel to work at the industrial titan’s plant in the community of Steelton, near Harrisburg. He took charge of Steelton’s baseball team, which competed against the company’s other plants and also played exhibitions against teams from outside Bethlehem Steel.52

This was no run-of-the-mill industrial league. During World War I, numerous professional ballplayers, including major leaguers, opted to take defense-related jobs rather than serve in the military, and officials at Bethlehem Steel’s plants competed to recruit them. One report in April 1918 said the Steel league’s accumulation of talent was becoming a concern for the majors. It called the league “the most powerful body of exploiting the national sport outside of the major circuits.” The headline summed it up: “Bethlehem Steel League Has Big Fellows Worried.”53

Future Hall of Famer and three-time World Series champ Eddie Plank, 41 years old, signed with Steelton, as did future Hall of Fame manager Joe McCarthy and 1912 World Series champion Steve Yerkes. Players who opted to play for other Bethlehem Steel plants included Babe Ruth, Shoeless Joe Jackson, Jeff Tesreau, Wally Pipp, and Dutch Leonard.54 Cockill’s Steelton team beat Bethlehem for the league championship in a 10-inning battle in mid-September.55

The Steel league briefly burned as hot as a blast furnace, but quickly cooled. By October 1918, a month before an armistice ended the war, most pro players who’d taken jobs in Steelton had left again – though Cockill was reportedly still “doing a full day’s work in the open hearth department.”56

After the big names went back to the pros, “the Steel” retained its in-house leagues as a perk for employees, and Cockill remained involved as player-manager.57 In July 1920, playing first base, he collaborated with former big-leaguer Roxey Roach to pull off a triple play for the Steelton team.58 Approaching his 39th birthday, Cockill was described as “not trained down to the condition that a good first baseman should be in,” as his lack of foot speed turned two potential doubles into singles.59

As his playing career wound down, Cockill returned to Bucknell as baseball coach in 1921 and 1922, resuming a position he’d held from 1915 through 1917. The Bison went 10-4 in his final season, and he ended his head-coaching career with a 41-35-1 record.60

He’d previously coached the football team in 1914 with a record of 4-4-161 and led the basketball team from 1914-15 through 1916-17, posting a record of 28-20-1. As of 2024, the 30-30 basketball tie Cockill coached against Susquehanna University on March 2, 1917, remained the only deadlocked game in Bucknell hoops history, going back to 1895.62 Cockill was elected to the college’s athletic Hall of Fame in 1984.63

The 1930 US Census found Cockill making $5,000 as a steel mill foreman, living in Steelton with wife Mary, 19-year-old son George Jr., and 4-year-old daughter Elizabeth.64 The following year he won election to Steelton Borough Council, running as a Republican and defeating two other candidates.65 He served in that local government position until April 1933, when he was appointed president of the Dauphin County Poor Board.66

Cockill was still serving on that board when he suffered a paralyzing stroke in January 1936 that left him in fragile health for the remainder of his life. He died at age 56 on the morning of November 2, 1937, in Steelton. A local sports columnist described Cockill as an inspirational leader on the field, and a man whose judgment was trusted when college coaches were evaluating student-athletes for potential scholarships.67

Cockill was survived by his wife and two children; a brother; three sisters; and two grandchildren. He is buried in Lewisburg Cemetery, which is, appropriately, adjacent to the Bucknell campus.68

Acknowledgments

This story was reviewed by Rory Costello and Len Levin and fact-checked by Jeff Findley,.

Sources and photo credit

In addition to the sources credited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. SABR member Brian McKenna’s article on the Bethlehem Steel League, cited in the notes, was a fascinating and informative primary source for the relevant section of this biography. The author thanks the Giamatti Research Center of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum for research assistance.

Image from the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, January 19, 1915: 9.

Notes

1 “George W. Cockill,” Bucknell University Athletics Hall of Fame website, accessed May 2024. https://bucknellbison.com/honors/bucknell-athletics-hall-of-fame/george-w-cockill/129.

2 Middle name from Cockill’s listing in the 1905 Bucknell University yearbook, L’Agenda: 37. https://archive.org/details/lagenda190500unse/page/36/mode/2up?view=theater.

3 “Thomas Cockill,” Pottsville (Pennsylvania) Daily Republican, November 16, 1931: 10; “Mrs. Thos. Cockill Very Ill,” Pottsville Daily Republican, November 27, 1902: 2.

4 “Minersville Mention,” Pottsville Daily Republican, December 4, 1902: 3; “Obituary,” Pottsville (Pennsylvania) Miners Journal, December 8, 1902: 4; “Thomas Cockill.”

5 “Thomas Clinton Cockill,” Familysearch.org, accessed May 2024, https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/LB4X-M12.

6 “Snow Balling Battle,” Pottsville Daily Republican, April 20, 1901: 4. The Pottsville paper attributes the story to a newspaper in nearby Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania.

7 “History,” Kutztown University website, accessed May 2024. As of 2024, Kutztown University had produced four major-league players. The most accomplished was pitcher Ryan Vogelsong, who won two World Series titles and made one All-Star team in a 12-season career between 2000 and 2016. https://www.kutztown.edu/about-ku/history.html.

8 “Keystone Anniversary,” Kutztown (Pennsylvania) Patriot, March 16, 1901: 1, https://cdm17189.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/patriot/id/8957/rec/4; “Keystone Normal School,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Daily Leader, June 27, 1901: 6.

9 “First Game a Big Victory,” Kutztown Patriot, October 6, 1900: 1, https://cdm17189.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/patriot/id/9017/rec/9; “Town Nine Got a Shut-Out,” Kutztown Patriot, June 22, 1901: 3, https://cdm17189.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/patriot/id/9010/rec/3.

10 “New Coach for Bucknell,” Kutztown Patriot, June 27, 1914: 10, https://cdm17189.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/patriot/id/14272/rec/8. The author of this biography was unable to find published reports of Cockill’s high-school athletic career. However, since Cockill starred in multiple sports at both Kutztown and Bucknell, it seems probable that he did the same at the high-school level as well.

11 It would seem that playing for a pro team would have made Cockill ineligible to play for Bucknell, as he would no longer have been an amateur. The author of this story can offer no explanation for the fact that Cockill played for a pro baseball team under his own name – being identified in several newspaper stories from the summer of 1901 – and then went on to play four more years of college athletics. While news stories from that summer refer to the player only by his last name, “George Cockill” is specifically named as a “former Pottsville pitcher” in “High School 20 Minersville 6,” Pottsville (Pennsylvania) Miners’ Journal, October 7, 1901: 1. As of May 2024, Baseball-Reference listed Cockill as a member of the 1901 Pottsville team but did not list statistics for him.

12 “Won Out in the Ninth,” Pottsville Daily Republican, August 3, 1901: 4.

13 Cockill and Mathewson did not cross paths at Bucknell. Mathewson broke into the major leagues in July 1900, and Cockill did not get to Bucknell until the fall of 1901. Cockill umpired games in which Mathewson pitched in 1915.

14 Cockill’s listing in the 1905 Bucknell University yearbook, cited above, and the 1906 yearbook: 39. https://archive.org/details/lagenda190600unse/page/38/mode/2up?q=cockill.

15 This record is compiled from Cockill’s listing in the 1905 Bucknell University yearbook, which covered his accomplishments through his junior year, and the university’s 2022 and 2023 record books in football, basketball and baseball, which are cited elsewhere in these notes.

16 F.B. Jaekel, “Review of Baseball Season,” 1905 Bucknell University yearbook: 206. https://archive.org/details/lagenda190500unse/page/206/mode/2up?q=cockill&view=theater. The season reviewed in the 1905 yearbook is actually 1903, Cockill’s sophomore year; future years’ Bucknell yearbooks confirm that he remained a first baseman.

17 “Football,” L’Agenda (Bucknell University yearbook), 1906: 215, https://archive.org/details/lagenda190600unse/page/214/mode/2up?view=theater.

18 Specifically, Sporting Life reported on page 4 of its March 17, 1906, issue: “Kockill [sic], the Albany first baseman, played for two seasons in the Tri-State league under the name of Potts.” https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll17/id/34971/rec/1.

19 “Turned Victory into Defeat,” Carlisle (Pennsylvania) Evening Sentinel, July 13, 1904: 3.

20 “In the World of Sport,” Miners’ Journal, January 13, 1905: 6. As of May 2024, Baseball-Reference identified the league as the Tri-State League, but news reports from 1905 called it the Susquehanna League. The eight teams listed by Baseball-Reference as league members were all based in one state, Pennsylvania.

21 Untitled news item, Milton (Pennsylvania) Miltonian, May 19, 1905: 3; “Base Ball Meeting at Sunbury,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Daily News, July 8, 1905: 1.

22 “Susquehanna League Disbands,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 11, 1905: 15.

23 According to the report, Cockill had been offered more money to come to Scranton but had chosen to stay in Shamokin because he had been promised offseason employment there. “Still Changing Make-up of Team,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Truth, August 5, 1905: 9.

24 “Cockill to Go to Detroit,” Pottsville Republican, July 27, 1907: 3.

25 “Tigers Set Some Great Records on Their Spring Training Trip,” Detroit Times, April 13, 1908: 2.

26 “Cantillon After Tiger Cockill,” Detroit Times, June 30, 1908: 2.

27 “Promising Tiger Kit Weds, Retires from Baseball,” Detroit Times, December 15, 1908: 7.

28 “Reading Baseball Franchise Is Bought by Coughlin and Cockill,” Harrisburg Telegraph, March 4, 1911: 1; “Tri-State Averages,” Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Semi-Weekly Intelligencer, September 27, 1911: 7; “Success Lies in Management in Tri-State Ball,” Wilmington (Delaware) Morning News, September 27, 1911: 10.

29 “Cockill Will Lead the H.A.C.,” Harrisburg Independent, January 10, 1912: 1; “Cockill Will Pilot Harrisburg Team,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Morning Tribune, January 12, 1912: 10.

30 “Harrisburg Ball Team Celebrated Pennant Raising by Winning Two Games from York,” Harrisburg Telegraph, September 4, 1912: 10; “1914 Pennant Is Swung on Island,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, September 7, 1914: 1.

31 Unheadlined one-liner, Harrisburg Telegraph, September 8, 1914: 6.

32 Cockill and Tener are known to have attended several baseball celebratory banquets during Cockill’s period as Harrisburg manager. They might well have encountered each other in other settings as well.

33 A Newspapers.com search for the phrase “Umpire Cockill,” run in May 2024, revealed a few cases of Cockill serving as umpire at college football games, but none in a baseball setting. Also, Retrosheet had no Sporting News umpire card on file for Cockill as of May 2024, suggesting that he had no other umpiring experience to record. A story that appeared in Pennsylvania newspapers in February 1915 said Cockill had “very little experience” but gave no supporting proof for even that claim. “Cockill Will Make Good,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, February 11, 1915: 8.

34 “Cockill’s Departure,” Harrisburg Telegraph, January 19, 1915: 6.

35 “Barber Shop Baseball,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, January 10, 1914: 8.

36 “Harrisburg Manager Who Will Become Ump in Tener Circuit,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, January 19, 1915: 8; online inflation calculator made available by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, accessed June 2024, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

37 “Cockill, Harrisburg’s Manager Made National League ‘Ump,’” Harrisburg Telegraph, January 19, 1915: 9; “National League Adopts Schedule,” Lancaster Morning Journal, February 11, 1915: 7; “National Adheres to Limit of 21 Players,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, February 10, 1915: 8; “Baker’s Retirement Puts Mack More on Defensive,” Brooklyn Times, February 17, 1915: 4.

38 “Umpire Cockill to Do Special Duty,” Harrisburg Telegraph, April 13, 1915: 12. The Braves’ planned home ballpark, Braves Field, was under construction in late May 1915; it opened in mid-August.

39 “Umpire Cockill a Little Too Speedy,” Philadelphia Evening Ledger, August 25, 1915: 12. Examples of positive news references to Cockill’s work: “Cockill Doing Good Work,” Lewisburg Journal, June 11, 1915: 3; “Praise for Cockill,” Reading (Pennsylvania) News-Times, August 18, 1915: 11.

40 “Eason Praises Retiring Pirate Manager,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, September 10, 1915: 10. This newspaper’s box score for the exhibition credits Mal Eason and Otis Stocksdale as umpires, but the box score on page 9 of the Chicago Tribune of September 10 lists Eason and Cockill.

41 “Personal Mention,” Lewisburg Journal, October 15, 1915: 5.

42 “Giants Beat Boston in Burlesque Game,” Boston Globe, October 8, 1915: 7. Both starting pitchers – Sailor Stroud for New York, Iron Davis for Boston – went the distance. Neither issued a walk, suggesting that hitters on both sides were lunging for the first pitch.

43 According to Retrosheet, NL umps got 625 home-plate assignments in 1915. Between them, Byron, Klem, Quigley, and Rigler handled 532 of the games, or 85 percent. “The 1915 Umpires by League,” Retrosheet, accessed May 2024. https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1915/YPU_1915X.htm.

44 A similar work pattern was in place in the 1915 Federal League, in which 467 of the 615 home–plate assignments (or 75 percent) went to just four umps – Bill Brennan, Bill Finneran, Jim Johnstone, and Barry McCormick. The American League was alone in more evenly distributing its home-plate assignments that season: Of the 10 umps to work in the AL in 1915, seven worked 70 or more games behind the plate.

45 “May Land Place as National Umpire,” Harrisburg Telegraph, August 5, 1915: 9.

46 “Cockill May Be Chosen Manager of Local Team,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Star-Independent, January 25, 1916: 1.

47 “Cockill Is Sore: Leaves for Home,” Harrisburg Telegraph, June 15, 1916: 10; “President Surrenders; Troy Team Comes Here,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, June 17, 1916: 11.

48 “Baseball Fans to Celebrate in Great Parade,” Harrisburg Courier, July 30, 1916: 1.

49 “Future League Game in Doubt; Farrell is Here,” Harrisburg Telegraph, June 6, 1917: 10.

50 “Harrisburg Barred from League Ball,” Harrisburg Courier, June 10, 1917: 1.

51 “York State League Club Owners Lose $50,000,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Evening News, September 1, 1917: 8. According to the online inflation calculator provided by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, $50,000 in September 1917 had the same purchasing power as almost $1.2 million in April 2024.

52 “State League Is in Bad Shape,” Harrisburg Courier, July 1, 1917: 5; “Formidable Teams in Steel League,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 18, 1920: 18.

53 “Bethlehem Steel League Has Big Fellows Worried,” Harrisburg Evening News, April 22, 1918: 13.

54 Brian McKenna, “Bethlehem Steel League,” SABR.org, accessed May 2024. Bethlehem Steel was not the only defense-related company to lure pro players into its recreational leagues, as McKenna’s article details. https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/bethlehem-steel-league/.

55 “6,000 Fans See Steelton Win Deciding Game from Bethlehem,” Harrisburg Telegraph, September 16, 1918: 11.

56 “Steel League Players Quit,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Evening News, October 7, 1918: 5.

57 “Formidable Teams in Steel League.”

58 “Bethlehem Wins Over Steelton,” Harrisburg Telegraph, July 12, 1920: 11. With two runners on base, Cockill caught a line drive at first base, stepped on the bag, and threw to Roach covering second.

59 “Former Tri-State Men Playing with Steelton,” Harrisburg Evening News, June 16, 1920: 12. As of May 2024, Cockill’s Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet pages did not list a playing or umping height and weight for him, and Retrosheet had no record of a Sporting News umpire card for him. The military draft card filled out by Cockill in September 1918 describes his height as “medium” and his build as “stout.” Draft card accessed via Familysearch.org in May 2024. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-L1JQ-8RK?i=1202&cc=1968530&personaUrl=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AK6VH-T57.

60 “Bucknell Baseball: Year-by-Year Records 1886-1990,” Bucknell University 2024 baseball record book, accessed August 2024: 3. https://bucknellbison.com/documents/2023/6/23/BASE_Record_Book_2024.pdf. Baseball-Reference’s Bucknell University page does not indicate that any players who played while Cockill was coaching later reached the major leagues.

61 Bucknell University 2023 football record book accessed May 2024: 56. https://bucknellbison.com/documents/2023/9/1/Record_Book_23.pdf.

62 “Year-by-Year Records,” 2023-24 Bucknell University men’s basketball record book, accessed May 2024: 2. https://bucknellbison.com/documents/2023/7/28/MBBRecordBook2324.pdf.

63 “George W. Cockill,” Bucknell University athletics Hall of Fame website.

64 1930 US Census listing for George Cockill and family accessed through Familysearch.org in May 2024. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ online inflation calculator (cited above), $5,000 in May 1930 had the same purchasing power as $92,765 in April 2024. Cockill’s son George was also working at the mill; his salary went unrecorded. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GRCD-6CB?view=index&personArk=%2Fark%3A%2F61903%2F1%3A1%3AXHS7-BH3&action=view.

65 A “borough” is one classification of independent community in Pennsylvania; other types are townships and cities. “Zerance Wins for Councilman,” Harrisburg Evening News, November 4, 1931: 9.

66 United Press, “Dauphin County Poor Director,” Shenandoah (Pennsylvania) Evening Herald, April 11, 1933: 8.

67 “George Cockill Dies in Steelton; Known as Athlete,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, November 2, 1937: 1; Al Clark, “The Sports Shop,” Harrisburg Telegraph, November 3, 1937: 20.

68 Christy Mathewson is buried in the same cemetery.

Full Name

George W. Cockill

Born

June 28, 1881 at Pottsville, PA (US)

Died

November 2, 1937 at Steelton, PA (US)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.