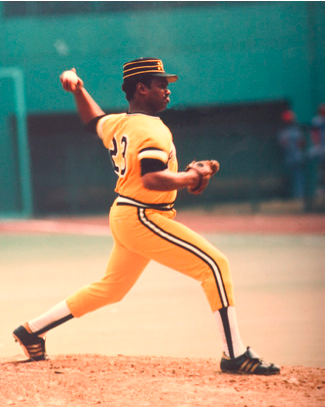

Grant Jackson

He pitched 18 seasons in the major leagues but for Grant Jackson, it all came down to one inning in the final game ever played in the 1970s. It was familiar territory for the left-hander. Eight years before, the Baltimore Orioles took a lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1971 World Series, which culminated with Game Seven at Memorial Stadium. Jim Palmer was still pitching for the Orioles, Earl Weaver managing, Frank Robinson back as a coach. In the opposing dugout, Willie Stargell, Manny Sanguillen, and Bruce Kison were holdovers from 1971. Jackson pitched in both contests but unlike any of the other players, he pitched in one Series for each side. He had appeared in relief for the Orioles in 1971. Now he was trying to win the World Series for “the ’Burgh.”

He pitched 18 seasons in the major leagues but for Grant Jackson, it all came down to one inning in the final game ever played in the 1970s. It was familiar territory for the left-hander. Eight years before, the Baltimore Orioles took a lead over the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1971 World Series, which culminated with Game Seven at Memorial Stadium. Jim Palmer was still pitching for the Orioles, Earl Weaver managing, Frank Robinson back as a coach. In the opposing dugout, Willie Stargell, Manny Sanguillen, and Bruce Kison were holdovers from 1971. Jackson pitched in both contests but unlike any of the other players, he pitched in one Series for each side. He had appeared in relief for the Orioles in 1971. Now he was trying to win the World Series for “the ’Burgh.”

The fourth son of Joseph and Luella Jackson’s nine children, Grant Dwight Jackson was born on September 28, 1942, in Fostoria, Ohio. In 2005 he told reporter Ron Musselman of the Toledo Blade that he retained fond memories of his hometown:

“Fostoria was a great place to grow up. I still go back there quite a few times a year. I have two sisters that still live there. And I help out some with the high school baseball team. … I enjoy working with the kids.”1 Jackson lettered in football, baseball, and track at Fostoria High School and once fanned 33 batters in a doubleheader at an American Legion tournament.2 Times were tough, however, for the Jackson family, as they were living on the lower end of the socioeconomic scale:

Joseph Jackson died of a heart attack in 1960, at age 52.3 Carlos Jackson, Grant’s older brother and also his biology teacher, then assumed the role of paternal influence “My dad, Joe … had the greatest influence on me when I was younger,” Grant said. “Those two took me under their wing at a very young age and helped make sure I did things the right way. My dad taught me how to be a man early on … to keep my nose clean and just keep working hard and things would work out.”4

Jackson graduated from Fostoria High in 1961 but his grades were too low to qualify for a scholarship to Bowling Green State University.5 That was when he decided to contact perhaps the most famous of Fostoria’s 15,000 residents, Philadelphia Phillies scout Tony Lucadello.6

Lucadello was remembered as “a great judge of talent” in his 32 years as a scout for Philadelphia.7 His pedigree included a virtual All-Star team of Midwestern athletes, including Alex Johnson, Mike Marshall, John Herrnstein, Toby Harrah, Mike Schmidt, and Mickey Morandini, along with Canadians John Upham and Fergie Jenkins.

Lucadello’s signing of Jackson was representative of an era when high-school athletes did not retain agents or hold press conferences, but rather relied on the good word of professional organizations. In 1962, the 6-foot, 190-pound Jackson signed for $1,500.8

“I signed on a Thursday,” Jackson recalled. “On Saturday, Ray Hayworth, who was scouting for the [Milwaukee] Braves, said he was prepared to give me $35,000. I had to tell him I’d already signed.”9 The family needed the money and Jackson could not afford the luxury of waiting two days for an offer he did not know would arrive. Years later, he admitted that “I wish then I could have called the Phillies back and told them I wasn’t going to accept their offer.”10

The 19-year-old Jackson began his professional career at Bakersfield of the then Class C California League, posting a record of 4-5 (5.79 ERA) in 1962. The league was reclassified to Single A before the next season, and Jackson improved to 12-8 (3.89) in 1963. A Bakersfield teammate, infielder Lou Garvin, tagged him with the nickname Buck.

“I reminded him of a cowboy when I walked to the mound. You know, bow legged, pigeon toed, walking like I was ready to draw a gun.”11 Jackson rose quickly through the Phillies system, to Eugene, Chattanooga, and finally Arkansas (Little Rock), where in 1965 he posted a record of 9-11 with a 3.95 earned-run average.12

Fergie Jenkins told how it was for Northern blacks unfamiliar with the racial climate in Little Rock. “Things were tenser, more overt in Arkansas,” he said. “One day we came out of the ballpark and found the car covered with signs and scrawls on the windows.” The messages were full of obscenities and racial invective. Position players like Dick Allen took the most abuse and was, for example, booed mercilessly when he misjudged a fly ball that landed for a double. Allen admitted that “these country hicks are getting me down, I can’t stand it.”13

Jackson’s tenure in Arkansas did not last long. He was called up to Philadelphia on September 1 when the rosters expanded and pitched in his first major-league game two days later in Cincinnati. His baptism at Crosley Field served as proof that he was now pitching in a higher league.

The Phillies were leading, 6-3, with two Reds runners on base and nobody out in the bottom of the fifth. Jackson was summoned to relieve Ray Culp, and struck out pinch-hitter Tony Perez and Deron Johnson on six pitches. Then he faced Frank Robinson. Ahead in the count 2-and-0, Robinson slammed the pitch over the emblematic Crosley Field scoreboard, into “Hudepohl Heaven” and toward Interstate 75, for a three-run homer. The Reds won 16-7 and Jackson was tagged with the loss.14 Despite the unpleasant initiation by Frank Robinson, the Phillies management retained their confidence in Jackson’s potential. He won his first game later in the month in relief, and struck out 11 Mets in nine innings while yielding one run during a no-decision start in the season finale. Pitching coach Al Widmar was convinced he was “headed for stardom.”15

Jackson had two short relief outings in April 1966, and was returned to the Pacific Coast League after Philadelphia acquired a pair of veteran starting pitchers from the Chicago Cubs. Fortunately for him, the Phillies had moved their Triple-A affiliate from Little Rock to San Diego. He was recalled again in September, but did not appear in the final month for the fourth-place club. Still, in 1967 he was in the major leagues to stay. By now the Phillies were an aging team and Jackson had hoped there would be room in the rotation for a young left-hander to complement Jim Bunning, Chris Short, Larry Jackson, and Ray Culp. Jackson did not like relief work and, according to Allen Lewis of the Philadelphia Inquirer, he “seldom did well coming out of the bullpen.”16 At the end of the 1968 season, his lifetime record was 4-10. The National League expanded to include two new teams and Jackson was disappointed that neither San Diego nor Montreal claimed him in the expansion draft. He wanted the opportunity to prove himself as a starting pitcher and was not getting it in Philadelphia.

Gene Mauch was fired as the Phillies’ skipper two months into the ’68 campaign. Under new manager Bob Skinner, Jackson was able to correct his delivery and improve as a pitcher. Unlike many young pitchers, often accused of pitching too quickly, Jackson’s workmanship was considered too slow and deliberate.

“We speeded him up on purpose,” said Skinner. “We want him to pitch fast. Before when he took his time, he went through check points instead of falling into a rhythm.”17 Widmar agreed, observing that Jackson “was trying to make every pitch a masterpiece.”18 As the 1969 Phillies headed north from Clearwater, Jackson was penciled as the fifth starter in the rotation. The Phillies had quickly sunk to the bottom of the National League East but defeated Pittsburgh 8-1 on April 12 to notch their first win of the season, with Jackson on the mound. He saved two of his better starts for the Cardinals, the defending National League champions, yielding only an unearned run on April 25 and shutting out St. Louis on May 4. Skinner was pleased with his pupil’s progress:

“He doesn’t pitch any faster than Bob Gibson. It’s just that he’s taking a completely different approach to pitching. He’s staying within himself.” Widmar concurred that Jackson “changed his delivery, the way he grips the ball, and he’s concentrating much better. We’ve got him throwing a fastball that sinks now.”19 Augmenting the sinking fastball in his repertoire were a slider, curveball, and changeup.20 He called his predominant pitch “a jive fastball,” which he described as “a fastball, hit it if you can catch up with it.”21

Jackson’s newfound poise earned him a berth as the Phillies’ representative at the 1969 All-Star Game in Washington. In what would be the only All-Star selection of his career, Jackson did not appear in the NL’s 9-3 victory at RFK Stadium. Despite a season record of 14-18, Jackson had earned the respect of both his coaches and his peers.

“He makes a lot of good pitches now and he doesn’t waste any time,” observed Phillies catcher Mike Ryan. “Get it and throw it, that’s the way he likes to pitch. We used the simplest signs when he’s pitching so as not to slow him down.”22 Jackson’s personal life was developing as well. While playing winter baseball in Puerto Rico, he met and married his wife, Milagros. Grant and Milagros had three children and lived year-round in Puerto Rico for much of his playing career.

Entering the 1970 season, the Phillies were rebuilding with Frank Lucchesi now as their manager. Jackson’s record in 1970 regressed to 5-15 with a 5.29 earned-run average. Frustrated at the lack of progress of his club, Jackson finally received his wish on December 16, 1970, when the Phillies traded him along with utilityman Jim Hutto and outfielder Sam Parrilla to the defending World Series champion Baltimore Orioles for outfielder and prized prospect Roger Freed. Never again would he post a losing record in the major leagues.

Jackson had hoped to join the Orioles rotation as the fifth starter but in a season when Dave McNally, Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar, and Pat Dobson each won 20 games, he was limited to nine starts with the 1971 Orioles.23 Under the tutelage of manager Earl Weaver and pitching coach George Bamberger, Jackson began to appreciate his role as a left-handed relief specialist:

“I like to start,” he told Lou Hatter of the Baltimore Sun. “That’s where the money is. … On the other hand, working out of the bullpen you’ve got to have a whole lot of saves, keep the earned-run average low, and slip in a few wins to get a big contract.”24 Though he did not register any saves in 1971, Jackson posted a record of 4-3 with a 3.13 ERA as the Orioles secured their third consecutive berth in the World Series. He pitched two-thirds of an inning in Game Four; both the game and the Series were 4-3 losses to the Pittsburgh Pirates.

It was during the 1972 season that Jackson entered his prime. After the All-Star break he won one and saved four while surrendering only four earned runs in 17 appearances. His success continued into 1973, when his season totals were nine saves, a 1.90 earned-run average, and an undefeated record of 8-0.25 As the Orioles hosted the Chicago White Sox on June 5, Jackson was credited with the decision in a comeback victory. The following night, Jackson got the save as the Orioles won again. Later that month, he contributed 5⅔ innings, allowing just one hit in a 16-inning marathon victory over the Texas Rangers. In this drawn-out affair, he retired the last 12 batters he faced. This outing occurred during a stretch in which Jackson hurled 14 straight scoreless innings bringing his ERA down to 1.19. From June 5 to 9, Jackson pitched in four of Baltimore’s five games:

“When he pitched the fourth [time],” observed Bamberger, “I felt he threw the ball better than in any of the three previous games. … That’s what makes Buck such an ideal bullpen man.”26 Jackson credited an exercise regimen of running, shagging fly balls, and playing “flip” toward his success, adding, “Call the bullpen, I’m ready! Just give me the ball!”27

In 1974 Jackson contributed a 6-4 record with 12 saves as the Orioles made their fifth postseason appearance in six years. His teammates noted that he was beginning to believe in himself: “Just being able to throw strikes in any situation without being nervous is the key to relief pitching. I don’t get upset easy. I try to keep everything easy. I don’t feel any pressure going in there.”28

In 1976 free agency arrived and rumors circulated that club owner Jerold Hoffberger was selling the Orioles. The order of the day was to cut payroll. Following his third consecutive subpar outing on June 13, Jackson had a 1-1 record with a 5.12 ERA for Baltimore. At the trading deadline on June 15, impending free-agent pitchers Doyle Alexander and Ken Holtzman were traded to the first-place New York Yankees for pitchers Rudy May, Tippy Martinez, Scott McGregor, and Dave Pagan, and catcher Rick Dempsey. Joining Alexander and Holtzman in the Bronx were catcher Elrod Hendricks and pitcher Grant Jackson. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner was jubilant about the trade, conveying to manager Billy Martin that “this trade just won you a pennant” and “you now have the best team on paper, and now you’re just a push-button manager.”29

The 1976 Yankees did, in fact, win their first American League pennant since 1964. Jackson contributed a record of 6-0 with an earned-run average of 1.69.30 But his postseason record was not up to his usual standards, as he surrendered five earned runs between the American League Championship Series and the World Series.

In November 1976 the Seattle Mariners “surprised everybody” by selecting Jackson in the expansion draft.31 Jackson never pitched an inning for Seattle; he was traded to Pittsburgh in December. The Pirates had won division titles in five of the previous seven years which translated into only one world championship. Competing with the Steelers’ NFL dynasty, the Pirates drew sparse crowds to cavernous Three Rivers Stadium. It was clear to new general manager Harding Peterson that second place was no longer good enough for the Pirates fans.

The Pirates boasted an abundant farm system that included Tony Armas, Al Holland, Rick Langford, Mitchell Page, Craig Reynolds, Jimmy Sexton, and Ed Whitson — players who would have kept the Pirates in contention well into the 1980s. Peterson had no objection to sacrificing the future in order to win immediately. The same day as the expansion draft, he dealt catcher Manny Sanguillen and $100,000 to the Oakland A’s for manager Chuck Tanner. Slugging outfielder Richie Zisk was traded to the White Sox for Rich “Goose” Gossage and Terry Forster — relievers who had pitched for Tanner in Chicago. In March 1977, a nine-player deal with Oakland landed infielder Phil Garner, while Reynolds and Sexton were dispatched to Seattle for Jackson. Joining a lineup that boasted sluggers Willie Stargell, Al Oliver, Ed Ott, and Dave Parker along with speedsters Omar Moreno, Bill Robinson, and Frank Taveras, the Pirates in 1977 became known as “lumber and lightning.” Stargell felt that Tanner’s influence would bolster attendance and put the Pirates over the top in the standings:

“Chuck’s optimistic outlook on life and enthusiastic personality bred life on our club. He was also a very innovative leader who rarely managed by the book. He created whatever results a situation necessitated, whatever way possible.”32

Tanner allowed his pitchers to bat after they had entered the game as a reliever. As Jackson himself remembered, “I took pride in knowing how to play the game, not just pitch. When you run the bases, you’ve got to run with your eyes wide open so you can see what’s going on around and you know what to do. If you know the game, then you know how to run the bases and you can help the team in another way.”33

Clad in their new disco-influenced black and gold attire, the Pirates raced toward the divisional lead in April and May before settling once again for second place. As Jackson remembered, it was a special season when the Pirates “had the best bullpen in baseball. Remember Goose Gossage? Terry Forster? [Kent Tekulve] and myself? All of baseball was saying if you got past the fifth inning and we were winning, you lost.”34 Indeed, the Pirates and their bullpen were credited with 34 wins and 39 saves in 1977. However, for the second year in a row, they finished in second place behind Philadelphia.

With Forster’s departure to the Los Angeles Dodgers as a free agent, Jackson became Chuck Tanner’s left-handed specialist in the bullpen. The Pirates fine-tuned their roster by trading the popular veteran outfielder Oliver to the Texas Rangers for starting pitcher Bert Blyleven and first baseman-outfielder John Milner in a four-team transaction during the winter meetings in December 1977. Sanguillen was reacquired from Oakland while hard-throwing pitcher Don Robinson was promoted from the minor leagues. Despite another fine season by Jackson out of the bullpen, the Pirates finished once again in second place, once again behind Philadelphia. The fans responded by staying home as the Pirates drew fewer than one million in 1978.

Additional roster changes were in order for 1979. Pitcher Jerry Reuss was traded to the Los Angeles Dodgers for Rick Rhoden while Rhoden’s teammate Lee Lacy joined him in Pittsburgh as a free agent. Meanwhile, reliever Enrique Romo was picked up in a deal with Seattle. Early in the season, the Pirates swapped shortstops with the Mets, sending Taveras to New York for Tim Foli. The Pirates responded by sinking to the bottom of their division, posting a 7-11 record by the end of April. What followed exemplified why Willie Stargell was the National League’s co-Most Valuable Player in 1979, both on and off the field:

“I kicked all nonplaying personnel out of the clubhouse. … My speech was simple. I reminded the guys that our slow start in ’78 had cost us the pennant. I told them to become more consistent — never too high, never too low. I told them to keep their minds in the gray area in between. Then I told them to just go out and play some good old country baseball, and most of all, to have fun.”35

True to the message of their theme song, “We Are Family,” the Pirates jelled as team with Stargell as the “Pops.” They went on to win 16 of their next 26 and vaulted into the pennant race by mid-July. Grant Jackson remained confident that he could get anyone out, no matter which side of the plate they faced.36 In 72 appearances, he went 8-5 with 14 saves and an earned-run average of 2.96.37 Once the Pirates returned to contention, it was not the Phillies but the Montreal Expos who gave them the most trouble. Jackson proved central to a critical moment of the season for both clubs.

After the Pirates acquired Bill Madlock in a blockbuster deal with the San Francisco Giants, the Expos, in the words of general manager John McHale, “had to counter” by trading for Rusty Staub.38 A folk hero in the early years of the franchise, Staub made his first plate appearance in Montreal as a pinch-hitter on July 27. A sellout crowd of 59,260 gave Staub the most raucous standing ovation ever awarded to an Expos player.39 With the Pirates ahead 5-4, two outs and a runner on in the eighth inning of the first game of a twi-night doubleheader, Staub faced Jackson amid a backdrop of deafening noise. Proving his statement that nothing ever bothered him, Jackson enticed Staub to slap an easy popup to Dave Parker in right field to end the inning. Pittsburgh won three games out of four in Montreal, making a statement that their early-season futility was little more than an aberration.

Pittsburgh and Montreal continued to fight a tough battle until the final day of the season when the Jolly Roger was raised over Three Rivers Stadium. Tanner continued to rely heavily on relievers Jackson, Tekulve, and Romo during the postseason after they combined for 250 regular season appearances. The Pirates swept Cincinnati in the best-of-five NLCS, thanks in part to Jackson’s perfect 10th inning in Game One. As the Pirates broke the tie in the bottom half of the inning, Jackson was credited with a 5-2 victory.40 His biggest fan it, would seem, was closer Kent Tekulve, who credited Jackson with “doing a helluva job” all season, especially early on when the Rubber Band Man was struggling.41

The 1979 World Series would be Jackson’s third of the decade, each with a different team. After Bruce Kison lit up the scoreboard with Orioles in Game One by surrendering five runs in the first inning, Jackson pitched a scoreless ninth as part of an impressive bullpen effort, albeit a losing one.42 “We lost the first game in that Series 5-4 but we weren’t worried. I remember breaking out the crabs and beer and partying to Sister Sledge.’”43

Jackson pitched again in Games Three and Four, extinguishing rallies both times before the Pirates received a double dose of “Oriole Magic.” Baltimore was now one game away from winning the World Series. “Even after we got down 3-1 in the Series, it bothered our fans but it didn’t bother us,” Jackson said. “We knew we had a better team than the Orioles.”44

When it mattered most, Jackson rose to the occasion. The Pirates were down 1-0 in Game Seven when he was summoned from the bullpen in the fifth inning to replace reliever Don Robinson. With two on and two outs, Jackson retired Al Bumbry on a foul pop to Madlock to end the scoring threat. In the sixth and seventh, Jackson retired every hitter he faced. Meanwhile, Willie Stargell did what team leaders are supposed to do in Game Seven of the World Series, as “Pops” put Pittsburgh ahead with a two-run homer in the sixth inning. The Pirates scored two insurance runs in the ninth as Tekulve earned a save in the bottom half of the inning. The Pirates were world champions.45

“Winning Game [Seven] of the 1979 World Series was my biggest thrill in baseball, no doubt. People from that era here in Pittsburgh still remember it like it was yesterday,” Jackson said.46 He credited the team for its collective success but believed that the championship would have remained elusive without its captain: “Willie Stargell was the star of our team. He was a great leader, on and off the field. He was one of the best players and best teammates I ever came into contact with. The day he died was one of the sorriest days of my life.”47

For his part, Jackson was impeccable in relief during the ’79 postseason. Winning two and losing none, he surrendered no runs and two hits in 6⅔ innings. The strongest accolades he earned were once again from Tekulve: “In 1979, this guy was my setup man, so they say. I didn’t look at it that way. He was my co-closer. Setup guys don’t save 14 games. … When you’re playing a major league baseball season, the whole idea when you go to spring training is you want to play in the last game of the season and you want to win that last game of the season because that means you are going to be the world champions. This guy won the last game of the season and made us world champions.”48

Even during the offseason, the Pirates remained a “family.” Jackson, by now living year-round in Pittsburgh, remembered attending Steelers games with Stargell, Parker, and Madlock in the offseason. “We’d sit up at the very top of the stadium. When it got too cold, we’d go down to the Allegheny Club and we’d sit in there with John Henry Johnson and just talk. The game would be over and we’d still be in there talking about things.”49

The Pirates’ celebration was short-lived. Despite a successful record of 8-4 on Jackson’s part, the team fell to third place in 1980 before plummeting to last place in the second half of the strike-shortened 1981 season. Jackson was sent in a cash deal to the Expos as the rosters expanded in September.50 Though he struggled in Montreal, he was rewarded by a Pittsburgh teammate once the season was over. After Bill Madlock won the batting title, “he gave [coach] Joe Lonnett and myself each $5,000 because we would throw extra batting practice for him all the time during the season.”51

In March 1982, Jackson was traded once again, to the Kansas City Royals for Ken Phelps.52 Posting a record of 3-1 with a 5.17 ERA in 20 appearances, Jackson was released at the All-Star break. He returned to Pittsburgh for one final game before retiring as a player. His career totals showed a record of 86-75 with 79 saves and an earned-run average of 3.46.53

The next chapter of Jackson’s career consisted of two decades as a coach in the major and minor leagues. In 1983 he became the Pirates’ bullpen coach, remaining as long as Chuck Tanner was the manager, until 1985. In 1994 he joined former Orioles teammate Davey Johnson in Cincinnati as the Reds bullpen coach. In between, he accepted minor-league assignments with the Cubs, Reds, and Orioles organizations. Asked if he tried to instill a philosophy among young pitchers, Jackson replied, “I tell them the good ones put into action what they have worked on and then make it work in games. I tell them to take some pride in what they do.”54

Did Jackson ever consider managing? “No” was his quick reply. “When you do that, you get gray hair, you get fat, and you start smoking. Lloyd [McClendon] doesn’t have any gray hair because he’s smart. He cuts it all off so you can’t tell.”55

Following the 2002 season as pitching coach for the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings, Jackson decided to retire from baseball. In 2004 he was part of the inaugural class of the Fostoria High School Hall of Fame. By 2005 he had as many grandchildren as are needed to field a team.56 The sandlot where he played as a child in Fostoria was renamed Grant Jackson Field in his honor. Not one to dwell on his individual accomplishments, Jackson said, “I would only focus on what the team did but if the team did well, then that meant everyone on the team was having some success. If someone asks me what my stats were, I tell them to talk to my wife. She knows all of that stuff much better than I do. All I know is, I signed my contract in 1962 and I retired in 2002. I had a lot of fun in between and it was all because of baseball.”57

Notes

1 Ron Musselman, “Baseball Very Good to Jackson,” Toledo Blade, June 19, 2005.

2 Musselman.

3 “Seizure Fatal to Joseph Jackson,” Findlay (Ohio) Republican-Courier, June 20, 1960: 15.

4 Ibid.

5 Musselman.

6 1960 US Census.

7 Fergie Jenkins, and Lew Freedman, Fergie: My Life from the Cubs to Cooperstown (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2009), 34.

8 Allen Lewis, “Rookie Jackson Front Runner in Race for Phil Starter Berth,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1966: 24.

9 Ibid.

10 Musselman.

11 Doug Brown, “Jackson a Stone Wall as Oriole Fireman,” The Sporting News, January 18, 1975: 50.

12 Lewis, “Rookie Jackson.”

13 Jenkins, 54-55.

14 Lewis, “Rookie Jackson.”

15 Ibid.

16 Allen Lewis, “Speed-Up on Hill Puffs Out Jackson’s Victory Bag,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1969: 21.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Bill Ranier and David Finoli, When the Bucs Won It All: The 1979 World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2005), 175.

21 Brown.

22 Allen Lewis, “Speed-Up on Hill Puffs Out Jackson’s Victory Bag.”

23 Brown.

24 Lou Hatter, “Jackson Shelves Curve to Outflank Bird Foes,” The Sporting News, July 7, 1973: 15.

25 Ranier, 174.

26 Hatter.

27 Ibid.

28 Brown.

29 Dan Epstein, Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ’76 (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2014), 175.

30 Ranier, 175.

31 Jack Lang, “Youth Has Its Fling in A.L. Expansion Draft,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1976: 34.

32 Willie Stargell and Tom Bird, Willie Stargell: An Autobiography (New York: Harper & Row, 1984), 180.

33 Rich Emert, “Where Are They Now? Grant Jackson,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 29, 2002.

34 Mike Mastovich, “Talking Baseball: Ex-Big Leaguers Entertain AAABA Crowd,” Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Tribune-Democrat, August 10, 2009.

35 Stargell, 192.

36 Lou Sahadi, The Pirates (Markham, Ontario: Fitzhenry & Whiteside Ltd., 1980),129.

37 Ranier, 176.

38 Maxwell Kates, “The Expos Emerge,” in Elysian Fields Quarterly, Vol. 23, No.4, 2006, Tom Goldstein, ed., 49.

39 Alain Usereau, The Expos In Their Prime: The Short-Lived Glory of Montreal’s Team, 1977-1984 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 58.

40 Ranier, 176.

41 Sahadi, 129.

42 Ranier, 63.

43 Musselman.

44 Ibid.

45 Ranier, 83-87.

46 Musselman.

47 Ibid.

48 Mastovich.

49 Emert.

50 Usereau, 126.

51 Emert.

52 Usereau, 153.

53 Emert.

54 Ibid.

55 Ibid.

56 Musselman.

57 Ibid.

Full Name

Grant Dwight Jackson

Born

September 28, 1942 at Fostoria, OH (USA)

Died

February 2, 2021 at Canonsburg, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.