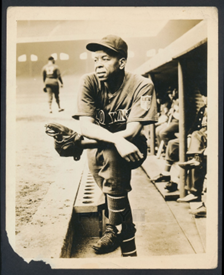

Jesse “Hoss” Walker

Hoss Walker was a baseball lifer. He enjoyed a 20-year playing career in Black Baseball and then managed for nearly a decade. Prior to playing a single game in the major Negro Leagues, he was a teenage pioneer playing a small role in growing the game of baseball in the Far East. He played with some of Black Baseball’s biggest stars on diamonds in Japan and Korea. Walker was born on September 10, 1911, in Austin, Texas. A “feisty infielder” and right-handed batter who was “clean cut and intellectual,”1 Walker stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 190 pounds. His birth year has long been published as 1904, but newly discovered research places his birth in 1911.2 Jesse’s mother, Ollie Tinnin (a laundress), was married twice – first to Fred Guest (a porter) in 1902, then to John Walker (a laborer) in 1919. Genealogy records suggest that Guest may have been Jesse’s biological father and that John Walker adopted Jesse after his marriage to Ollie in 1919.3

Hoss Walker was a baseball lifer. He enjoyed a 20-year playing career in Black Baseball and then managed for nearly a decade. Prior to playing a single game in the major Negro Leagues, he was a teenage pioneer playing a small role in growing the game of baseball in the Far East. He played with some of Black Baseball’s biggest stars on diamonds in Japan and Korea. Walker was born on September 10, 1911, in Austin, Texas. A “feisty infielder” and right-handed batter who was “clean cut and intellectual,”1 Walker stood 5-feet-11 and weighed 190 pounds. His birth year has long been published as 1904, but newly discovered research places his birth in 1911.2 Jesse’s mother, Ollie Tinnin (a laundress), was married twice – first to Fred Guest (a porter) in 1902, then to John Walker (a laborer) in 1919. Genealogy records suggest that Guest may have been Jesse’s biological father and that John Walker adopted Jesse after his marriage to Ollie in 1919.3

Sometime in the early 1920s, Walker moved to California. In the July 17, 1921, issue of the Austin American, Ollie Walker stated that her husband, “Jake Walker,” was killed. It’s quite possible that Jake was indeed Ollie’s husband John, and that this tragic event was the catalyst for the Walker family’s move west.4

In 1925 at age 14, Walker joined the Los Angeles Railway Panthers, a team managed by Robert Fagan, former second baseman of the Kansas City Monarchs, St. Louis Stars, and the 25th Infantry Wreckers, an all-Black US Army team that featured Bullet Rogan, Heavy Johnson, and Dobie Moore.5 By the following summer, Walker was playing third base with Fagan and O’Neal Pullen for the Los Angeles White Sox.6

The White Sox, managed by Lonnie Goodwin, were a top Black team that sometimes played in the integrated California Winter League (CWL). In the summer of 1926, the team barnstormed between CWL campaigns. In July, they played a highly publicized two-game series with the Fresno Athletic Club, managed by Japanese baseball pioneer Kenichi Zenimura. Fresno won both games, but Zenimura was impressed and recommended that Goodwin take the team to Japan for a tour.7

After the 1926-27 CWL season, Goodwin did just that, recruiting several players from his Philadelphia Royal Giants squad for a tour of the Pacific, years before Babe Ruth’s All Americans went to the Far East. Negro League superstars Biz Mackey, Andy Cooper, Rap Dixon, and Frank Duncan, all members of the first-place Royal Giants, formed the team’s nucleus. Walker was among the players Goodwin invited to fill out the lineup. Jesse was just 15 years old at the time but lied on his paperwork to make himself appear seven years older.

The Giants played 24 games in Japan, winning 23 (with one tie) from April through mid-May.8 From there they went to Korea, winning all five contests they played.9 They spent June in Hawaii, playing 11 games (winning nine). Walker played in every game in Hawaii, hitting .250 (10-for-40) with a pair of doubles.10 He made just two errors.11 Once back on the mainland, Walker joined Pullen on his Los Angeles Giants team.12

After the 1927-28 California Winter League season, the two Black clubs in the circuit, the Philadelphia Royal Giants and the Cleveland Stars, continued to barnstorm. Walker may not have played for either team during league play, but he appears to have played a part-time role for both during their exhibitions. For example, in mid-March Walker was the starting third baseman for the Cleveland All-Stars, managed by Pullen.13 Just a week later, he was injured in a serious car accident with the Philadelphia Royal Giants when the team was traveling between venues. Walker, Mackey, Frank Warfield, Crush Holloway, Jesse Hubbard, and Pullen required hospitalization.14

In July Walker was again recruited by Pullen for a Hawaiian tour organized by Goodwin, this time with the Cleveland Giants. Mackey, Dixon, Cooper, and Duncan did not join this tour, opting to return to their Negro League clubs. The Hawaii papers noted that Walker was “back and he is very much improved,” with his defense characterized as “nothing short of sensational.”15 The Giants returned to Los Angeles in September.16

The following spring, Jesse was back in Hawaii with the Pullen Giants (this time featuring Mackey, Dixon, George Carr, and Connie Day).17 Walker hit .305 in 15 games on the tour and made just two errors in 67 chances.18

Upon returning to the mainland, Walker made his major Negro Leagues debut (in the American Negro League) with the Atlantic City Bacharach Giants. He was joined on the club by his Pullen Giants teammates Day, Carr, Ping Gardner, and Joe Cade. Starting at shortstop and third base, he hit .248 in games available on Seamheads. After the Bacharachs disbanded, Walker played with Pullen and Carr on the Milwaukee Giants in 1930.19

In 1931 Walker joined the Cleveland Cubs for their only season in the Negro National League. The team got a few appearances from a 24-year-old Satchel Paige but had an otherwise modest roster. Walker was the everyday shortstop and hit .235. During the season, Newspapers began using his “Hoss” nickname.20 Nearly every reference to him in the press from then on used the moniker. That winter, he played in the California Winter League for the first time. As the Philadelphia Royal Giants’ second baseman, he joined a star-studded lineup that featured Mule Suttles, Willie Wells, Cool Papa Bell, and Vic Harris. The rotation included Paige and Willie Foster. The team went 22-2.21

Walker joined the Nashville Elite Giants of the Negro Southern League in 1932, the only season in which the circuit is classified as a major league. Again the starting shortstop, he hit .273. After the season, Nashville (the second-half champion) squared off against the Chicago American Giants (the first-half champion) in the NSL Championship Series.22 Chicago won the series four games to three.

Walker was back in the California Winter League after the season. His team was called the Nashville Elite Giants, but the roster was much different from the NSL squad (including Satchel Paige, Sam Bankhead, and Alex Radcliff in addition to his summer teammates Jim Willis and Felton Stratton). In 26 box scores collected by William McNeil, Walker hit .349 and tied for the league lead with 10 doubles.23

Nashville joined the second Negro National League in 1933 and Walker got the majority of starts at second base despite the presence of the 22-year-old Sam Bankhead. Among 37 box scores on Seamheads, Walker got into 20 games and hit just .169. The following season, Bankhead won the starting job for Nashville and Walker appeared in just 15 games among those on Seamheads (though he managed to hit .300).

The Elite Giants relocated to Columbus for the 1935 season. Hoss appeared in just five of 31 box scores for the team (hitting .176), and also appeared in two of 40 box scores for the Newark Dodgers (going 1-for-7). Despite the limited playing time, Walker played in the North-South All-Star Game in Memphis that September. He started and batted eighth for the North team (which featured Cool Papa Bell, Oscar Charleston, and Wild Bill Wright) and went 0-for-3.24

In 1936 Walker moved with the Elites to Washington, where he was again the starting shortstop. In 45 box scores, Walker appeared in 27 and hit .308. The Center for Negro League Research reports that Walker also managed the Nashville Black Vols of the NSL in 1936. Tom Wilson, owner of the Elite Giants, also served as the president of that league.25 Walker spent the 1936-37 winter in the California Winter League with Wilson’s Royal Giants, though he does not appear to have been a starter.26

Back with Washington in 1937, Walker appeared in all 37 known box scores and hit .238 as the starting shortstop. In the winter he played with the Philadelphia Royal Giants again in California. The stacked team featured Bell, Mackey, Suttles, Wright, Sammy Hughes, Leroy Matlock, and Chet Brewer. In 10 available game records, Walker hit .405 with three home runs (leading to an uncharacteristically high slugging percentage of .703).27

In 1938 the Elites went to Baltimore and Walker played a utility role (hitting .256 in 25 box scores). He also appeared for the Memphis Red Sox three times, going 1-for-11. Walker stayed with Memphis for the playoffs as they faced the Atlanta Black Crackers in the NAL Championship Series (by being first-half champions). The series was halted after just two games were played. Walker started both and went 2-for-8 with a pair of doubles.28 In October Walker played in his second North-South All-Star Game, starting at shortstop for the South and going 0-for-3 with a sacrifice in the 3-1 victory over the North.29

Walker was again an All-Star in 1939 (starting at shortstop for the North and collecting two hits) and returned to the playoffs, this time with Baltimore. In the series against the Newark Eagles (won by Baltimore, three games to one), he appeared in one game, getting two hits in two at-bats. In the five-game Negro National League Championship Series, he appeared in three games and went 0-for-6 as Baltimore surprised the Homestead Grays to win the pennant. Back in California that winter, Hoss played second base for the Philadelphia Royal Giants.30

Walker spent the 1940 season with the New York Black Yankees (and also played a pair of games with Baltimore). Now 30 years old and the starting shortstop, he hit just .156 in 26 box scores found on Seamheads. He split the 1941 season between the Black Yankees and Birmingham Black Barons. Hoss was again the starting shortstop for Birmingham in both 1942 and 1943, returning to the postseason in 1943 as first-half champions. Birmingham faced the Chicago American Giants in the NAL Championship Series and won the five-game series three games to two. The Black Barons advanced to the Negro World Series against the mighty Homestead Grays, who prevailed by winning four of the eight games. (One was a tie.) Box scores are available for seven of the games. Walker played in six of them, going 3-for-20 (.150) with a double. In the winter, Hoss returned to the California Winter League with the Baltimore Elite Giants.

Before the 1944 season, Walker was traded to the Cincinnati-Indianapolis Clowns for John Britton.31 He was named the team’s manager and shared the starting shortstop duties with Henry Smith.32 It was his first of many major-league managing roles. A “teacher and coach in the offseason,” Walker was “loved and completely respected by his players.”33 The team still entertained fans with clowning in nonleague matches, but had done away with such hijinks in league contests.34 The team improved from sixth place in the NAL to third under Walker’s tutelage. Walker again played winter ball in California with Chet Brewer’s Kansas City Royals.

In 1945, the Clowns slumped back to fifth place in the NAL. After the season Walker appeared in a handful of games in California for the Royals. Overall, in parts of nine CWL seasons recorded by William McNeil, Walker hit .328 and slugged .480 in 73 games – far above his Negro Leagues offensive performance.

The Clowns improved to second place in 1946, as Walker reduced his own playing time significantly (with Coco Ferrer and Gene Smith splitting most of the starts at shortstop). In August he was honored with “Hoss Walker Night” in Nashville as his Clowns faced the Nashville Cubs of the Negro Southern Association.35

Hoss was one of three Clowns managers in 1947, sharing the duties with Willie Wells and Reinaldo Drake. The team finished fifth, but was slightly better under Walker’s guidance (17-23) than the others (23-49-2). Walker continued to back up the third base and shortstop positions.

Walker joined the Baltimore Elite Giants as manager for the 1948 season. The legendary manager Candy Jim Taylor was set to begin his first season leading the Elites in 1948, but died in April just before the season began. Walker was brought in to replace Taylor (with Henry Kimbro briefly acting as manager in the interim).36 By this time, Walker had almost completely stepped back as a player, inserting himself into only three league games during the season. Baltimore had a very strong team with an exceptional rotation (headlined by Bill Byrd and Joe Black) and a robust lineup featuring Kimbro, Lester Lockett, Tommy Butts, and a young Jim Gilliam. The Elite Giants finished second in the league to a dominant Homestead squad led by Luke Easter. The two teams squared off in the League Championship Series and the Grays emerged as winners in controversial fashion. After Homestead won the first two games, the squads entered the ninth inning of the third match tied, 4-4. Homestead scored four times in the ninth to take an 8-4 lead, but the game was called before it reached completion (due to an 11:00 P.M. curfew). Baltimore won the fourth game 11-3, but when the league ruled that the third game would resume at the point at which it was halted (with the Grays up 8-4 rather than tied), Baltimore chose to forfeit and hand the series to the Grays.

In 1949 Walker was chosen to manage the East in the East-West All-Star Game.37 His squad won 4-0 behind a combined two-hitter by Bob Griffith, Andy Porter, and Patricio Scantlebury.38 Baltimore won the East Division (the Negro American League had split into Eastern and Western Divisions in 1949) with a 59-30 record and faced the Western Division’s Chicago American Giants in the playoffs. (The Kansas City Monarchs had won the Eastern Division but did not participate in the playoffs because so many of its players had been signed by the American and National Leagues).39 Baltimore swept Chicago to win the championship.40 Walker was ejected from the deciding game for arguing with and shoving umpire Virgil Bluitt. He was handed a 10-game suspension.41

Hoss avoided the suspension by leaving the Negro American League, purchasing his hometown Nashville Cubs of the NSL, and naming himself the manager.42 In December of 1950, Walker was announced as manager of the Raleigh Tigers.43 However, by the time the Tigers NSA campaign kicked off, Fred Worthy was installed as skipper.44 Instead, Walker returned to Baltimore one last time to manage the Elite Giants for the 1951 season.45 Baltimore finished second in the East – but well below .500 and far behind the first-place Indianapolis Clowns.46

In 1953, Walker rejoined the Birmingham Black Barons as manager. Birmingham finished a distant second (of four teams) to the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro American League.47 He once again took part in the East-West All-Star Game as a coach for the East squad.48 In all, he made four All-Star appearances in his career – two North-South games (both as a player) and two East-West games (one as a manager and another as a coach).

Willie Wells began the 1954 season as Birmingham’s manager, but Walker replaced him in July.49 Birmingham finished third in the expanded six-team circuit.50 Despite already being announced as Birmingham’s manager for 1955,51 Walker started the season with the Detroit Stars of the Negro American League. He lasted until June before being replaced by Ed Steele.52 His last managerial role came in 1956 with one last turn for the Black Barons.53

After his career in baseball, Walker worked as a janitor in Nashville and lived with his second wife, Gustavia. Walker had previously been married to Hattie Bush Walker, but they had split up by 1950.54 Walker died suddenly on February 10, 1971, at just 59 years old, his cause of death not reported. In addition to Gustavia, he left behind six daughters (all of whom lived in Nashville) and two grandchildren.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the authors used Baseball-Reference.com and the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, as of December 13, 2023.

Photo credit: Hoss Walker, courtesy of RMY Auctions.

Notes

1 Alan J. Pollack, Barnstorming to Heaven: Syd Pollock and His Great Black Teams (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2012), 150.

2 Bill Staples Jr., “The International Origins of Jesse ‘Hoss’ Walker’s Storied Negro Leagues Baseball Career,” International Pastime, http://billstaples.blogspot.com/2023/03/the-international-origins-of-jesse-hoss.html, accessed November 26, 2023.

3 Staples. The occupations of Fred Guest and John Walker are as reported respectively in the 1900 and 1920 US Censuses.

4 Staples.

5 “Farley Knocked Out of Box but the Panthers Win,” California Eagle (Los Angeles), April 23, 1926: 7.

6 “Pirrone’s Colts Easy for Sox Who Take Doubleheader,” California Eagle, July 2, 1926: 7.

7 Coop Daley, “Breaking Barriers, Crossing Oceans: The History of Black Ballplayers in Japan, Part I,” JapanBall, https://japanball.com/articles-features/japanese-baseball-historical-profiles/breaking-barriers-black-ballplayers-in-japan/, accessed December 11, 2023.

8 Kazuo Sayama and Bill Staples Jr., Gentle Black Giants: A History of Negro Leaguers in Japan (Fresno: Nisei Baseball Research Project Press, 2019), 27.

9 “Rogan’s Giants Make Fine Record During Japan Tour,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 6, 1927: 27.

10 “Heavy Hitting by Giants,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 1, 1927: 36.

11 “Shortstop Pounds Out 18 Hits; Filipino Team Plays Errorless Ball,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 1, 1927: 16.

12 Staples, “The International Origins of Jesse ‘Hoss’ Walker’s Storied Negro Leagues Baseball Career.”

13 “Beavers Take 4 to 3 Decision in Fast Game,” Anaheim (California) Bulletin, March 19, 1928: 6.

14 “Slippery Paving Injures Ten Men,” Bakersfield (California) Morning Echo, March 24, 1928: 1.

15 “Collection of Best Negro Baseball Players To Be in Honolulu on Friday,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 14, 1928: 11.

16 “Royal Giants Win Two Games Over Weekend in Stadium,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 15, 1928: 29.

17 “Pullen Giants Play Between Loop Games; Impressive Opening Ceremonies Are Planned,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, March 23, 1929: 9.

18 “Giants’ Records,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, May 17, 1929: 35.

19 “Colored Players,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 16, 1930: 24.

20 “Louisville Takes First from Cubs,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 20, 1931: 14.

21 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 156.

22 Retrosheet, “1932 Negro League Postseason,” https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/1932PS.html, accessed November 26, 2023.

23 McNeil, 160.

24 Retrosheet, “North All Stars(N) (NAS) 6 South All Stars(S) (SAS) 4,” https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1935/B09290SAS1935.htm, accessed November 26, 2023.

25 Dr. Layton Revel, “Forgotten Heroes: Henry Kimbro,” Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/Henry_Kimbro%202019-10.pdf, accessed November 26, 2023.

26 McNeil, 262.

27 McNeil, 190.

28 Retrosheet, “1938 Negro League Postseason,” https://www.retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/1938PS.html, accessed November 26, 2023.

29 Retrosheet, “South All Stars(S) (SAS) 3 North All Stars(N) (NAS) 1,” https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/1938/B10020SAS1938.htm, accessed November 26, 2023.

30 McNeil, 200.

31 William J. Plott, Black Baseball’s Last Team Standing: The Birmingham Black Barons, 1919-1962 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2019), 149.

32 “Leads Negro Club Here,” Muncie (Indiana) Evening Press, June 27, 1945: 10.

33 Barnstorming to Heaven: Syd Pollock and His Great Black Teams, 150.

34 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 810.

35 “Hoss Walker Night,” Nashville Banner, August 6, 1946: 15.

36 Riley, 810.

37 “Hoss Walker to Manage Giants,” Weekly Review (Birmingham, Alabama), July 29, 1949: 5.

38 Retrosheet, “East All Stars(E) (ASE) 4 West All Stars(W) (ASW) 0,” https://retrosheet.org/NegroLeagues/boxesetc/EW/B08140ASW1949.htm, accessed November 26, 2023.

39 Dr. Layton Revel, “Negro American League Standings (1937-1962),” Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Standings/Negro%20American%20League%20(1937-1962)-2020.pdf, accessed November 26, 2023.

40 Riley, 50.

41 “Victorious Manager, ‘Hoss’ Walker, in Ten-Day Suspension in ’50 for Dispute,” St. Louis Argus, September 30, 1949: 21.

42 “Sports of the World,” Atlanta Daily World, February 19, 1950: 7.

43 “Hoss Walker to Pilot Raleigh Tiger Nine,” Baltimore Afro-American, December 16, 1950: 18.

44 “Raleigh Nips Stars, 9-7; Routs Sox,” New Journal and Guide (Norfolk, Virginia), April 22, 1950: 19.

45 “Elites Here Tomorrow,” Baltimore Evening Sun, August 4, 1951: 9.

46 “Negro American League Standings (1937-1962).”

47 “Negro American League Standings (1937-1962).”

48 “East-West Pilots, Coaches, Named,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 11, 1953: 11.

49 “Jesse ‘Hoss’ Walker Replaces Wells as Birmingham Black Barons’ Pilot,” Chicago Defender, July 24, 1954: 24.

50 “Negro American League Standings (1937-1962).”

51 “Change of Pace,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 1, 1955: 13.

52 “Steele Replaces Walker as Manager of the Stars,” Chicago Defender, June 18, 1955: 10.

53 “Jesse ‘Hoss’ Walker Manager Black Barons,” Huntsville (Alabama) Mirror, June 2, 1956: 7.

54 “The International Origins of Jesse ‘Hoss’ Walker’s Storied Negro Leagues Baseball Career.”

Full Name

Jesse Walker

Born

September 10, 1904 at Austin, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.