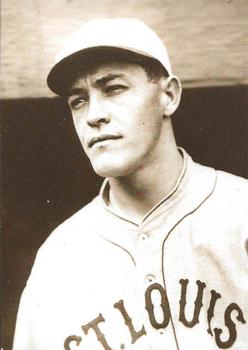

Hub Pruett

Hub Pruett was an unassuming lefty with a screwball so good that Babe Ruth once told him, “If all pitchers were like you, no one would have heard of me.”1 But Pruett’s peak was brief. It served merely as the prologue to a lengthy and remarkable career outside the game.

Hub Pruett was an unassuming lefty with a screwball so good that Babe Ruth once told him, “If all pitchers were like you, no one would have heard of me.”1 But Pruett’s peak was brief. It served merely as the prologue to a lengthy and remarkable career outside the game.

Hubert Shelby Pruett was born on September 1, 1900, in Malden, Missouri, to “prosperous farmer and stock dealer”2 Shelby Pruett and his wife, Grace.3 Shelby died when Hubert was four years old—Pruett family lore holds that he was in a carriage that overturned,4 though contemporary accounts suggest that an illness took the elder Pruett.5 Gracie, as she was known, was suddenly a single mother of five boys—Hub, his older brothers Elonzo and William, and his younger siblings Vernon and Robert. Gracie sent her children to school in Dexter, Missouri. When Hub graduated, the family dedicated the funds necessary to send him to the University of Missouri.6

Two things happened to Hub Pruett sometime in his youth, though the chronological particulars are lost to us now. But first of all, he was saddled with the nickname “Shucks” because, it was said, that was the saltiest word in his vocabulary.7 The second event of importance was his making the acquaintance of Barney Pelty. Pelty was a righty curveball specialist who debuted with the Browns in 1903 and hung on with them for a decade before finishing up with a stint in Washington. Pelty was from Farmington, Missouri, and remained in the Show Me State once he retired from the game, keeping busy with a variety of ventures, including coaching high school sports. Young Pruett, like most baseball-loving boys of the era, worshipped Christy Mathewson, and longed to learn Matty’s signature pitch, the fadeaway. Pruett approached Pelty and, in Pruett’s own words, “asked him if I could learn the fadeaway even though I was a left-hander. Barney said he would coach me and pretty soon I was throwing it pretty well.”8

Presently the young Pruett was suiting up for the University of Missouri Tigers, and his specialty pitch was the key to his success. “By the time I was pitching for the varsity at the University of Missouri,” said Pruett, “the opposing hitters weren’t getting a foul off the fadeaway. I threw the fadeaway three ways. Thrown overhand, it acted somewhat like a slider—it moved out. Underhand [sidearm], the ball nose-dived—this was my big strikeout pitch. I also threw it with a three-quarter motion. Any way I threw it, the ball would break sharply away from a right-handed batter, break into a left-handed hitter.”9

The southpaw soon drew the attention of St. Louis Cardinals scout Charley Barrett, who told the hurler that if he ever wanted to play pro ball he should head up to St. Louis and the Cards would see what they could do for him. Pruett did just that, presenting himself at the Cardinals’ office one day in June 1920, after his first year of college had wrapped up. But the Redbirds were on the road, and so, finding no one at the team’s office at 3623 Dodier Street, he wandered to the Browns’ suite, located around the corner at 2911 North Grand Boulevard, where he encountered Bob Quinn, the American Leaguers’ business manager. Quinn greeted Hub, listened to his story, and asked if Pruett had his heart set on playing big-league ball for the Cardinals, or if he just wanted to play big-league ball. Hub said it didn’t matter to him, so Quinn offered to let Pruett work out for Browns manager Jimmy Burke. Burke was impressed, so the Browns offered Pruett a contract. After some thought, Hub returned to his studies.10

In spring 1921, Pruett again suited up for the University of Missouri Tigers. Early that season, the team traveled to play Washington University in St. Louis. Now that he was securely on their radar, the Browns sent scout Pat Monahan to offer Pruett a chance to reconsider.11 This time he signed.

When he reported to the Browns, the 5-foot-10, 165-pound Pruett was banged up. “I was a sore-armed pitcher from the day I broke into Organized Baseball,” he would later say. “I broke three ribs pitching for Missouri University in my last year of college ball and I was never again able to throw freely.”12 The Browns sent their bruised acquisition down to the Tulsa Oilers of the Class A Western League, where he saw action in 30 games in 1921, totaling 135 innings of work, giving up an even 100 runs. He won four games for the last place club and lost seven.

Pruett broke camp with the Browns in 1922, but he saw no game action for the first couple of weeks of the season. He finally made his major-league debut on April 26 at Sportsman’s Park, when he entered the game in the ninth and held Detroit scoreless in an eventual 2-0 loss. Pruett next appeared on May 8 in Washington when he relieved Dave Danforth, down two runs in the fourth inning. Hub struck out the Senators’ Bucky Harris before getting a bit shaky, walking the next two batters, retiring Joe Judge on a ground ball, then allowing Sam Rice to score on a wild pitch. Pruett finished the frame by striking out Frank Brower. In all, Hub pitched four innings, giving up that one run but otherwise avoiding damage, and the Browns scored twice in the seventh and twice more in the ninth for a comeback win.

Acknowledging Pruett’s effectiveness, manager Lee Fohl gave the southpaw a start in the series finale. Pruett pitched into the fifth and though he was a little wild—surrendering five bases on balls—he earned the win in a 5-3 Browns victory.

Hub did an inning of mop-up duty against the A’s in a lopsided defeat on May 15 and then sat for a week. When he was next summoned, the Browns were visiting the Yankees at the Polo Grounds. With the game tied at three, New York had Mike McNally on first in the bottom of the ninth inning. Pruett got Elmer Miller to pop out to the first baseman and Aaron Ward to line out to third to end the inning.

In the bottom of the 10th, with the score still knotted, Ruth strode to the plate. Pruett broke out the fadeaway, and Ruth went down swinging. They next faced each other on June 12, when Hub was again given the start. He struck Ruth out in the first, walked him in the fourth, struck him out in the sixth, and again in the eighth. The press loved it. They told of how the “puny collegian”13 was “poison to Ruth.”14

On July 12, the Browns and the Yankees met again. Pruett made the start, inducing the Babe to ground out to first in the inaugural frame, strike out swinging in the third, strike out looking in the fifth, and strike out swinging in the sixth.

On August 25, Hub came in with the bases loaded, none out, and Ruth up. He fanned the Babe once more.

The most momentous meetings between Pruett’s Browns and Ruth’s Yankees came during a three-game series in St. Louis in mid-September that would all but determine the American League pennant. Given the importance of the games, it was dubbed “The Little World Series.”

New York took the opener, 2-1, behind a strong start by Bob Shawkey. The middle game featured Waite Hoyt on the mound for the Yankees. Fohl countered with Pruett, starting his eighth game of the year, his 36th appearance overall. Hub struck out Whitey Witt and Joe Dugan to start the contest, then walked Ruth, but got lucky when Wally Pipp tried to stretch a single and was put out at second, stranding the Babe at third.

Hub struck out Ruth in the fourth, and the game remained scoreless until the sixth when, with two out and nobody on, Ruth again swaggered to the dish. With the count at 2-2, Hub reared and delivered. Babe deposited the offering over the wall in right. Yankees 1, Browns 0, and Ruth’s blanking at Hub’s hand ended. But the Browns weren’t quite sunk. In the bottom of the inning, third baseman Eddie Foster walked and George Sisler singled him to second, extending his hitting streak to 41 games in the process. Ken Williams drove in Foster, and Hank Severeid knocked in Sisler and Williams. In the eighth, Williams homered to right with Sisler on base to make the score 5-1.

Pruett, meanwhile, was cruising, with Ruth’s homer the only hiccup. The Yankees had a little something going in the top of the ninth with Shucks still pitching, but the threat ended on a nifty double play when Hub struck out Wally Schang and catcher Severeid nailed Pipp trying to steal his way into scoring position.

While Ruth had to a degree solved Pruett, at least on this afternoon, Hub’s line was impressive: one run on five hits, eight strikeouts, and a single walk. The victory brought the Browns back to within a half-game of New York, with one more head-to-head matchup the following afternoon.

The day after Pruett’s gem, Bullet Joe Bush took the mound for the Yankees and the Browns countered with Dixie Davis. Both righties pitched well, keeping the game scoreless until the fifth when Severeid cashed in Baby Doll Jacobson. Marty McManus knocked in Ken Williams in the seventh to make it 2-0, St. Louis. The Yanks scored one in the eighth to make it 2-1.

Davis retook the hill in the ninth but gave up a leadoff single to Schang, who then scampered to second on a wild pitch. Fohl turned to Pruett, who only the day before had thrown a full nine innings. Hub’s balky arm was tired, and he wouldn’t manage to record an out. McNally laid down a bunt that Severeid couldn’t field in time. Pruett then walked Everett Scott to load the bases.

Fohl had seen enough. He sized up his bullpen and opted for Urban Shocker, calling the veteran in on one day’s rest. Hope flickered when Shocker got the first out on a force at the plate, but Witt singled to score McNally and Scott. Shocker finished the inning by getting Dugan to ground into a double play, 5-4-3.

Suddenly trailing 3-2, the Browns could muster nothing in the ninth as Sisler, Williams, and Jacobson went down in order. Pruett, whose runners Shocker had inherited, was stuck with the loss. In the span of 24 hours, he had gone from hero to heel, and the Browns slipped another game back. St. Louis won six of nine games down the homestretch after the Yankees series, but it wasn’t enough. They finished the season exactly one game behind New York.

Pruett had thrown 119 2/3 innings in his rookie year, with an opponent’s batting average of .235. In 15 plate appearances, Pruett had struck Ruth out nine times, walked him three, and allowed him only two hits, including a home run.

On September 27, Pruett left the Browns to resume his studies.15 “My early ambition was to be a doctor, and I never started to be a ball player,” he later said. “When I was pitching for the University of Missouri, it never occurred to me that my little curve could fool big league hitters. Then, when an offer came to play pro ball, I accepted with the idea of earning some money while working my way through medical school.”16

“He doesn’t dissipate,” the Dexter Statesman wrote of Hub. “He saves his money. He gets $3000 for six months with the Browns, and he salts down 2 out of every three to pay his way in the university in the winter.”17

Hub returned to the team in spring 1923. The Browns’ season began with a pair of losses to Ty Cobb and the Tigers at Sportsman’s Park. Pruett started the second game and was roughed up, surrendering seven runs (six earned) and taking the loss. He pitched in relief twice over the next few days, and started again at Detroit, giving up five runs and taking his second loss. After four appearances, Pruett was 0-2 with an ERA of 6.19.

His arm still hurt. The winter had done little to heal it, and no sooner had the season started when Lee Fohl began to lean heavily on his crafty second-year left-hander, tasked with starting or finishing games depending on circumstances, and rarely given more than a day or two between outings.

Pruett got his first shot at Ruth that year at home on May 16. Fohl inserted Hub in relief of Elam Vangilder in the eighth, down 4-1. Hub walked Joe Dugan. The Babe followed Dugan in the order. Shucks sat him down on three pitches. Pruett faced Ruth 13 times in 1923, and Ruth didn’t fare much better than he had the year before, eking out a sacrifice and four walks, a pair of hits including a homer, while striking out five times.

But overall, Hub had come back down to earth. He would finish the season with a 4-7 record, an ERA that ballooned to 4.31, and considerable discomfort in his left arm. His inning total was down to 104 1/3. Without George Sisler—who missed the season while suffering the aftereffects of a sinus infection that had interfered with his vision—and with a few other players backsliding, the Browns sank to the second division.

The club improved to fourth place in 1924, but Pruett was good for only 65 innings of work, almost exclusively in relief. He returned to the Browns for the 1925 season, but his arm troubles continued, and the team optioned him to Oakland of the Pacific Coast League.18 His peregrinations had begun.

He threw 209 innings for the Oaks in 1925. He threw another 277 in 1926. Ahead of the 1927 season, Hub latched on with the Phillies, appearing in 31 games and going 7-17 for a team that lost 103 games. The Phillies put him on their reserve list for 1928, and he returned to provide steady work through most of the summer, until the club sold him to the Newark Bears of the International League. Bears manager Tris Speaker leaned on him heavily down the stretch and then brought him back for 1929. All the while, Pruett was keeping up his medical studies, taking classes at several universities, whichever institution was closest to wherever he happened to be playing ball.19

At the end of the 1929 season, none other than John McGraw purchased Hub’s contract from Newark with the aim of slotting him into the Giants rotation. Pruett worked 135 2/3 innings in 1930 with middling results, which failed to impress McGraw. “Hub,” he said, “you’d make one of the greatest pitchers in the business if you’d keep your mind on baseball instead of on medicine.”20

In spring training 1931, Hub’s mind wandered too far from the game for Muggsy’s liking. The Sporting News said the skipper was “not paying much attention to Pruett, who has asked permission to continue his hospital work until late in May.”21 The Giants held onto him until the end of June, then shipped him back to Newark.

Hub had made no secret of his plan to retire once he began to practice medicine, and he was nearing the end of his studies. Baseball had done just about everything he’d needed it to. He got one more trip to the majors when the National League’s hard-luck Boston club picked him up for the 1932 season. He appeared in 18 games, starting seven of them, but by the end of the year Boston’s manager, Bill McKechnie, was echoing McGraw, telling Pruett that he ought to concentrate on medicine. “Your patients need you,” wrote The Sporting News, putting words in McKechnie’s mouth, “and my patience is gone.”22

Hub graduated from St. Louis University as a Doctor of Medicine on June 7, 1932.23 It had taken 13 years of schooling and 12 seasons of pro ball to get him there. He’d studied at St. Louis University, the University of Chicago, Washington University in St. Louis, the University of Tennessee, and Rush University, always returning to St. Louis University to write his exams and to intern.

He never made it back to the American League after leaving the Browns, so he never had another chance to face Ruth on a ball field. His final professional record, across all levels, was 92 wins against 103 losses. He’d racked up 1,791 innings of work. He took the Missouri state medical exam in January 1933, and then Dr. Pruett slipped away from baseball as easily as he’d slid into it, moving instead into a lifetime of service.24

While still with the Browns, Hub had married Elsie Borgmann, and the couple had lived with her parents in a house on Sullivan Avenue in St. Louis, about a block east of Sportsman’s Park. When he retired from baseball, Hub set up his medical practice on St. Louis Avenue, just south of the ballpark.25 He and Elsie eventually had two daughters, Mary Jane and Marjorie, and two sons, Hubert, Jr. and Don, raising them all in a house in Ladue, a suburb west of downtown St. Louis.

In June 1948, Pruett saw Babe Ruth again. It was the first time they’d spoken, the first time they’d met outside of the simple binary arrangement of a mound and a plate. The occasion was a luncheon in St. Louis in Ruth’s honor. Ruth was quite ill; in a month he’d be dead.

Hub thanked the Babe for putting him through medical school. “If it hadn’t been for you,” he told the slugger, “I would have been a baseball unknown. Whatever fame I had was due to you.” Ruth expressed gratitude that not all pitchers were like Shucks, then told the physician, “If I helped you through school, I feel proud of it, and it gives me a source of much satisfaction.”26

Pruett sponsored Little League teams and played in Old Timers games. He did repairs around the house, injuring his back in 1958 after falling while trying to fix a downspout.27 He watched his sons play football,28 and he played in dads-vs.-dads baseball games at John Burroughs Preparatory School with his old teammate George Sisler.29 He wrote a book called Baseball Hygienics.30 He collected jazz records.31

He treated Dizzy Dean’s sore pitching arm,32 and when Lefty Leifield returned from a quail-hunting trip with some pellets in his leg, Shucks patched him up. Leifield had pitched for the Browns a few years before Hub, then turned to coaching. He’d helped the young Pruett with his curveball. When Lefty asked what he owed for the medical services, Pruett said, “Not a thing.”33

Pruett’s name surfaced from time to time in the baseball press as a curio, a fun fact, a where-are-they-now piece. The doctor who struck out Babe Ruth. It seems likely that his unusual story popped back into the heads of writers for the St. Louis-based The Sporting News as they encountered him around town. There are times of the year when baseball stories are few and far between, and Shucks was always right there.

Pruett also turned up in George Plimpton’s 1961 book Out of My League. The writer/amateur athlete included an anecdote featuring a conversation between two old-time fans watching his exhibition performance on the mound at Yankee Stadium after the 1958 season. Pruett was the subject of friendly bickering about how often one of the men mentioned the pitcher’s name.

Elsie died in 1972.34 Hub continued to practice medicine, putting in 41 years once all was said and done. He lived almost 50 years after he’d thrown his last big-league pitch. He died in Ladue on January 28, 1982.35 His remains were thereafter interred in Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to James Pruett, grandson of Hub, for a lengthy and illuminating conversation on March 17, 2023, which proved instrumental in directing the research.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Bill Lamb and fact-checked by Jeff Findley.

Photo credit: Hub Pruett, Trading Card Database.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed below, the author also consulted Ancestry.com, Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Stan Mockler, “He Could Fool Babe Ruth and Did it with Sore Arm,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1955, 15.

2 “Shelby Pruett Dead,” Malden (Missouri) Press-Merit, Friday, July 14, 1905, 4.

3 The family name appears as “Pruitt” in data from the 1900 US Federal Census, with Shelby’s name rendered “Sheby,” and Hubert’s listed as “Herbert.” The 1910 Census restores proper spelling of Hubert Pruett’s name.

4 Anna McDonald, “Pruett Heir remembers Ruthian Legacy,” ESPN SweetSpot, March 2, 2014. Accessed September 5, 2024, https://www.espn.com/blog/sweetspot/post/_/id/44743/pruett-heir-remembers-ruthian-legacy.

5 “Shelby Pruett Dead,” above.

6 “A Close-Up of Hubert “Shucks” Pruett, Pitcher,” Dexter (Missouri) Statesman, June 2, 1922, 1.

7 McDonald.

8 Gerald Holland, “A Pitch that Baffled the Babe,” Sports Illustrated, May 18, 1964.

9 Holland.

10 Mockler.

11 Bob Broeg, “Birds Battle Brownies in Dinner Loop,” The Sporting News, January 30, 1952, 8.

12 Mockler.

13 Billy Evans, “Puny Collegian May Win Pennant for the St. Louis Americans,” (Bartlesville, Oklahoma) Morning Examiner, July 7, 1922, 4.

14 Billy Evans, “Pruett Uncrowns King of Swat,” New Castle (Pennsylvania) Herald, July 20, 1922, 8.

15 “‘Shucks’ Pruett Leaves Browns to Resume Work at Missouri University,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, September 28, 1922, 6.

16 Dr. Hubert Pruett (as told to Frederick G. Lieb), “My Greatest Diamond Thrill,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1944, 11.

17 “A Close-Up of Hubert “Shucks” Pruett, Pitcher,” above.

18 The Sporting News Player Contract Cards, ScanID: 1099019434 Hubert S. Pruett. Accessed January 11, 2024, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/104021/rec/2.

19 Mockler.

20 Maurice O. Shevlin, “The Sporting Mill,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 6, 1936, 13.

21 Joe Vila, “Giants Speed Work with Terry in Fold,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1931, 1.

22 “Training Camp Notes,” The Sporting News, March 16, 1933, 5.

23 “530 Candidates Will Get Degrees Tuesday from St. Louis U.,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 5, 1932, 14.

24 ““Shucks” Pruett, Former Brownie Hurler, Takes State Medical Exams,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 3, 1933, 8.

25 “Dr. Pruett Practices Near Scene of Diamond Thrills,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1944, 11.

26 Oscar Kahan, “Bambino and Pruett Meet Socially for First Time,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1948, 11.

27 “Dr. Hub Pruett, Ex-Pitcher, Injures Back in Fall at Home,” The Sporting News, June 25, 1958, 39.

28 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1949, 34.

29 “Major Flashes,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1948, 28.

30 Oscar Ruhl, “From the Ruhl Book,” The Sporting News, August 29, 1951, 16.

31 Bob Broeg, “King Carl: Superb Mound Craftsman,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1970, 18.

32 “Dizzy Dean Doomed to Stay with Cards,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1937, 10.

33 Dick Farrington, “Diz Now Ranks High in Cards’ Affection,” The Sporting News, December 3, 1936, 3.

34 “Obituaries: Mrs. Elsie Borgmann Pruett,” The Sporting News, March 17, 1972, 52.

35 “Obituaries: Dr. Hubert S. Pruett,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1982, 62.

Full Name

Hubert Shelby Pruett

Born

September 1, 1900 at Malden, MO (USA)

Died

January 28, 1982 at Ladue, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.