Hurley McNair

Early Black baseball figure Hurley McNair played professionally from 1910 through 1937. Yet despite being a key cog of the dominant Kansas City Monarchs lineups of the 1920s, the outfielder remains relatively unknown.

Early Black baseball figure Hurley McNair played professionally from 1910 through 1937. Yet despite being a key cog of the dominant Kansas City Monarchs lineups of the 1920s, the outfielder remains relatively unknown.

Statistics can build a legacy. But when stats are hard to come by, legacies are built by stories. Nothing crafts a compelling tale like a singular, seemingly superhuman skill—the prodigious power of Josh Gibson; the blazing speed of Cool Papa Bell; the dazzling “Bee-Ball” hurled by Satchel Paige. The blueprint for being overlooked is the jack of all trades and master of none—the ballplayer who can do it all but does not have that transcendent tool that makes fans and historians wax poetic.

The modern game has new metrics that better quantify a player’s overall contributions. These statistics measure contact, patience, power, and speed; they also capture details such as a player’s daring on the basepaths or opposing runners’ reluctance to try to advance on their arm. Through this modern lens, we can identify players whose excellence was not fully recognized (such as Larry Walker, Minnie Miñoso, Ron Santo, or Alan Trammell) and retroactively bestow on them the accolades they deserve.

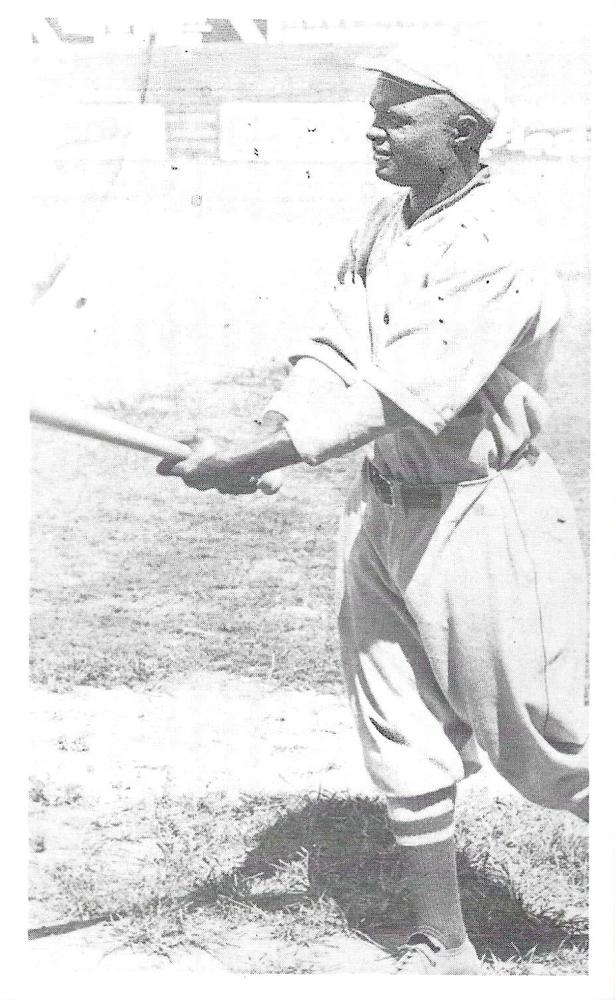

Of course, the Negro Leagues also had players with this profile—and McNair was one of them. A left-handed batter and thrower, his posthumous scouting report from premier Negro Leagues researcher Larry Lester effused about how he “hit to all fields” with both frequency and authority. He was a “speed merchant” who had a plate discipline that was far ahead of its time. Standing 5-foot-6 and weighing 150 pounds, the “original toy cannon1” possessed “Popeye-like arm strength” in the outfield—and, in his younger days, on the mound. Lester summarized that McNair “leads the league in excitement.”2 Endorsing this assessment is the statistical record compiled decades after McNair’s death by Negro Leagues researchers like Lester and the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database team.

Allen Hurley McNair was born October 28, 1888, in Marshall, Texas, a city near the Texas-Louisiana border about 40 miles west of Shreveport. Hurley (already using his middle name by the 1900 Census) was the son of Nelson McNair, a “fashionable barber”3 who was called “a worthy colored man.”4 Nelson went into business in 1868,5 one year before marrying his first wife, Jane.

The identity of Hurley’s mother is less clear. It certainly was not Jane, who died in 1880. Nelson married Tempy (or Tempie) Shavers in 1883, making it most likely that she is Hurley’s mother. Nelson married Victoria Calloway in 1898; it is unclear if Tempy and Nelson had separated, if Tempy passed away, or if Nelson had any relationships in between Tempy and Victoria that could have resulted in Hurley’s birth.

Hurley had several half-siblings, as Nelson and Jane had at least four children (Hannah in 1869, Nelson Jr. in 1872, Florence in 1876, and “Neely” or “Neal” around 1878). By 1900, Hurley was living with Hannah, Florence, and a pair of other siblings or half-siblings: Mattie (born in 1881) and Willie (born in 1886). At this time, Nelson was living with Victoria and three more children that may have also been Hurley’s half-siblings.

In Marshall, McNair began playing (and possibly managing) a team called the “Marshall Ned Ideas.”6 By 1910, he was playing professionally for Houston of the Texas Negro League.7 That season, the Minneapolis Keystones (managed by Bill Gatewood) came barnstorming through Texas and faced Houston. McNair started on the mound and defeated the Keystones, 3-2. Gatewood was impressed and signed McNair and his catcher, James Wills, before returning to Minnesota.8

McNair finished 1910 and began 1911 with the Keystones and was the team’s top hitter (.355 batting average and .632 slugging percentage) and pitcher (15-7).9 In May, he crushed three home runs while tossing an 8-3 victory against the Louisville Cubs. The Keystones folded in July10 and McNair latched on with the Kansas City Giants for the rest of the 1911 season. He made a pair of pitching appearances with the Giants that raised his stock in Black baseball—first defeating the Chicago American Giants (with Rube Foster on the mound) in September and then throwing seven scoreless, one-hit frames against the American Association’s Kansas City Blues in October. That game was called a scoreless stalemate on account of darkness after seven innings.11

The decade was a nomadic one for McNair, who played for several teams (over the next few years—and often many per season. In 1912, he played outfield and pitched for the Chicago Giants (managed by Joe Green), Brooklyn Royal Giants (managed by Grant “Home Run” Johnson), and the Kansas City Royal Giants (managed by Topeka Jack Johnson). In 1913, he joined W. S. Peters’ Chicago Union Giants and may have returned to the Chicago Giants and Kansas City Giants. His 1914 was mostly spent with the Chicago Union Giants and possibly another brief appearance for the Kansas City Royal Giants.12

McNair joined Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants for the 1915 season. In 59 games (as compiled by Seamheads), he hit .292/.351/.361 (a 139 OPS+) as the starting right fielder. By this point, he had essentially transitioned into a full-time position player while scattering a few more pitching appearances over the remainder of his career. Chicago faced the New York Lincoln Stars (managed by John Henry Lloyd and featuring Dick Redding, Louis Santop, Spottswood Poles, Bill Pierce, and Bill Pettus) for the “Colored Championship of the World.” The nine-game series was tied at four games apiece heading into the pivotal final contest. The game was called after just four innings with New York ahead by a single run. It was never replayed, and the Lincoln Stars declared themselves the winners of the series. Foster considered the series a tie.13

McNair joined Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants for the 1915 season. In 59 games (as compiled by Seamheads), he hit .292/.351/.361 (a 139 OPS+) as the starting right fielder. By this point, he had essentially transitioned into a full-time position player while scattering a few more pitching appearances over the remainder of his career. Chicago faced the New York Lincoln Stars (managed by John Henry Lloyd and featuring Dick Redding, Louis Santop, Spottswood Poles, Bill Pierce, and Bill Pettus) for the “Colored Championship of the World.” The nine-game series was tied at four games apiece heading into the pivotal final contest. The game was called after just four innings with New York ahead by a single run. It was never replayed, and the Lincoln Stars declared themselves the winners of the series. Foster considered the series a tie.13

Following the season, the American Giants played in both the integrated California Winter League and in Cuba, but McNair did not travel with the team for either trip. He later played in California but doesn’t appear to have ever played in Latin America.14 McNair married Emma Jackson in 1916.15 Perhaps the marriage was the reason he didn’t accompany the team.

McNair started the 1916 season with the American Giants before rejoining the Union Giants.16 In 1917, he played with the Lost Island Giants, a new resort team co-owned by Robert Gilkerson and William “Bingo” Bingham. The team entertained resort guests in Arnold’s Park, Iowa on Lake Okoboji.17 During his time with the Lost Island Giants, he appeared at least once for the Chicago Union Giants.18 Later in the year, McNair joined J.L. Wilkinson’s All Nations team. There, he played with several of his future Kansas City Monarchs teammates, including Bullet Rogan19, José Méndez, John Donaldson, Cristóbal Torriente, and Bill Drake.

It is unclear where McNair played in 1918, which has led to speculation that he served in the military during World War I. In the 1930 Census and on his death certificate, he is explicitly listed as not being a veteran. Nonetheless, for decades, several prominent Negro Leagues researchers (such as Jerry Malloy,20 James Riley,21 John Holway,22 William McNeil23, and Dr. Layton Revel24) have stated that McNair was a member of the U.S. Army’s 25th Infantry Wreckers, a dominant all-Black regiment team stationed in Hawaii and Arizona in the years surrounding World War I. The Wreckers featured several of McNair’s future Monarchs teammates (including Rogan, Dobie Moore, Heavy Johnson, Lemuel Hawkins, and Bob Fagan).

However, the author has conducted extensive research on the Wreckers25 and found no mention of McNair in over 200 box scores and game stories. John H. Nankivell’s history of the 25th Infantry includes a section on the famous baseball team that mentions Rogan, Moore, Johnson, Hawkins, Fagan, and several others—but not McNair (although there is a photograph from 1924 that includes a white officer named “Lieutenant McNary”). McNair may have been playing ball somewhere in 1918, but it almost certainly was not for Uncle Sam.

In 1919, McNair was playing with the Chicago Union Giants when he received an invitation from J.L. Wilkinson to join the 1920 Kansas City Monarchs in the maiden season of the Negro National League. Union Giants teammate Rube Curry also made the move. Donaldson, Méndez, and Sam Crawford joined from the Detroit Stars. Rogan, Moore, and Fagan joined from the 25th Infantry Wreckers with Heavy Johnson joining the Monarchs in 1922 after his discharge.26

By the time McNair debuted for the Monarchs, he was 31 years old with a decade of experience in Black baseball. Pre-1920 Black baseball statistics are not extensive, but Seamheads has records from 96 games that McNair played against top Black clubs prior to joining the Monarchs. In those games, he hit .331 with a .383 on-base percentage and .459 slugging percentage. McNair pitched in 13 of those contests, going 5-3. The Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research has a bit more data (117 games, likely including some games against lower-level competition). In that data set, McNair hit .349 with a .500 slugging percentage27 and 20-12 pitching record.28

McNair was an instant success upon joining the Monarchs, playing left field and leading the team in hits (103) and OPS (.849). He finished among the top 10 in the new Negro National League in just about every offensive category. As a “student of the game,” he excelled in all areas of his craft and shared this knowledge with younger players. Hall of Famer Willie Wells gave McNair “a lot of credit for teaching me how to become a better hitter.” Teammate George Sweatt shared that McNair would “take you to his room and tell us the different plays, how to play the position, and what men to watch. [He knew] every man in the league.” George Giles remembered that McNair “gave me a few ideas about shifting and standing different on different pitchers.”29 Giles added that “Mac could have taken two strikes on Jesus Christ and base-hit the next pitch.”30

The 1920 Census reports McNair renting a home in Kansas City with his wife Emma and his mother-in-law, also named Emma (Jackson). He was also living with Thelma Petway (nine years old) and Junior Allen Maxey (four years old and incorrectly transcribed as “Jamison Maxie”), listed as his adopted daughter and son. Hurley’s sister Leanna died in 1917 and it appears that Hurley and Emma stepped up to care for her family. Thelma (born in 1910) was the child of Leanna (McNair) and Sam Petway. It is less clear who Junior’s father is—and even if his mother was definitely Leanna. The timing of Leanna’s death coupled with McNair’s new family responsibilities could explain the gap in his playing career in 1918.

In the winter of 1920-21, McNair played for the Los Angeles White Sox in the integrated California Winter League (CWL). The CWL featured many players from the major leagues and the high minors, including many stars from the Negro Leagues. The White Sox were stacked with Kansas City Monarchs players. In addition to McNair, the team boasted Rogan, Moore, Curry, Hawkins, and George “Tank” Carr. McNair was one of the league’s offensive stars, hitting .313 and leading the league with 11 doubles and six triples. He also pitched once, a complete-game win.31

In 1921, McNair proved his 1920 NNL season was no fluke by essentially repeating his production. Once again, his name appeared in the league’s Top 10 of most categories as he hit .344 and led the Monarchs in hits, extra-base hits, and runs batted in. McNair also pitched a little for the Monarchs, starting three games and appearing once more in relief. He spent the winter back in California, this time with the Colored All-Stars of the CWL. McNair, Moore, Carr, Fagan, and Hawkins were joined by Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston, Biz Mackey, and Méndez. McNair batted .290 with a league-leading six triples. He was also 4-1 on the mound.32

McNair had the best season of his career in 1922, hitting .374 and leading the league in walks and on-base percentage. He once again ranked in the Top 10 in just about every category. He pitched three more times, including his final documented start. Following the season, the Monarchs avenged their 1921 postseason series loss to the American Association’s Kansas City Blues by defeating their white city rivals in five of six games. Following that series, they defeated Babe Ruth’s barnstorming All-Stars in a pair of games.33 It is unclear if McNair played in the CWL that winter. William McNeil lists him with the Los Angeles White Sox but provides no statistics.34

The Monarchs won their first pennant in 1923 and McNair was again a huge part of the team’s success. He hit .327 with power and speed, setting a career high among recorded games with 23 steals in his age-34 season. He once again led the Negro National League in bases on balls.

The Monarchs repeated as league champions in 1924 to earn a spot in the first Negro World Series against Hilldale, winners of the Eastern Colored League. After excelling again during the regular season (hitting .339), McNair struggled mightily against Hilldale. Per Larry Lester, he was the “Least Valuable Player” of the series, hitting just .143 (5-for-35) with no extra-base hits and just a single run batted in. Despite that, he played a big part in the Monarchs’ come-from-behind win in Game Eight, singling to drive in Rogan in the ninth and later scoring the winning run. Overall, he left 32 men on base (15 of them in scoring position),35 but the Monarchs still managed to win the series in 10 games (five wins, four losses, and a tie).

In the winter, he returned to the Los Angeles White Sox, but appeared in less than half of the team’s games. When he was in the lineup, he hit well (.407 in 15 games).36 This was his last appearance in the California Winter League. His known overall stats in the circuit included a .322 batting average and .513 slugging percentage in 79 games.37

McNair hit .332 in 1925 as the Monarchs won their third straight league title. They faced the second-half champion St. Louis Stars in the playoffs and prevailed, four games to three, while McNair hit .316. In a World Series rematch, Hilldale quickly disposed of Kansas City in six games (winning five). McNair batted .273 with a pair of doubles in the series.

McNair entered the 1926 season at 37 years old. His batting average finally dipped below .300 for the first time (.297). The Monarchs continued to excel, winning the Negro National League’s first half to set up a playoff clash with the second-half champion Chicago American Giants. After winning four of the first five games, the Monarchs dropped four in a row to crash out of the playoffs. McNair struggled again, hitting .103 in his final postseason appearance. Overall, in 31 career playoff games, he hit just .190 with three doubles.

In 1927, McNair’s final season with Kansas City, his batting average dipped to .278. After the season, he was traded along with George Mitchell and Grady Orange to the Detroit Stars for future Hall of Famer Andy Cooper.38 McNair hit .274 for Detroit in 1928, sharing outfield duties with Turkey Stearnes, Torriente, and Wade Johnston.

McNair may have commenced the 1929 season with Detroit, but by the end he was playing for Gilkerson’s Union Giants.39 McNair had previously played for Gilkerson in 1917 with the Lost Island Giants. The Union Giants were one of the top barnstorming minor Black ball clubs in the country. McNair played with the team in 193040 and 1931, when they had a particularly strong lineup that boasted Torriente, Alex Radcliff, and Steel Arm Davis.41

In 1932, McNair joined John Donaldson’s All-Stars for a barnstorming tour of the Midwest. In eight box scores discovered by the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, McNair hit .424 (14-for-33).42 The following season, McNair played for and managed the semipro Arkansas City Beavers (from Arkansas City, Kansas).43 The Beavers, with former Monarchs pitcher Alfred “Army” Cooper as their ace, played in the Kansas championship tournament against other top semipro clubs. Following the tournament, McNair and Cooper joined an all-star team of tournament participants to face the Kansas City Monarchs.44 They lost, 15-1.45

McNair returned to the Monarchs in 1934 for the first time since 1927. The club played an independent schedule that season, barnstorming as far as Canada (often facing Grover Alexander’s House of David squad).46 In August, the Monarchs participated in the Denver Post Tournament, a prestigious semipro competition that was open only to white clubs in its first 19 years. The Monarchs were the first Black club invited to participate. The House of David also registered for the tournament but bolstered its roster with the addition of Satchel Paige and catcher Bill Perkins. In response, the Monarchs supplemented their lineup with Turkey Stearnes, Bill Foster, and Sam Bankhead.47 The Monarchs lost the championship game to the House of David, but it was Miles “Spike” Hunter rather than Paige who defeated Chet Brewer, 2-0.48

McNair seems to have started the 1935 season with Kansas City,49 but does not appear in any available box scores. By May, McNair was playing for the independent Paseo Taverns50 (also often referred to as the McNair All-Stars). Former Monarch Dink Mothell also played for the Taverns.51 It is unclear where McNair played in 1936, but he played a few games in 1937 with the Cincinnati Tigers of the Negro American League. When the Tigers faced the Monarchs for a Sunday doubleheader in May, the 48-year-old McNair was batting cleanup in both contests.52 In July, he played for Newt Joseph’s All-Stars.53

Following the 1937 season, McNair traded playing for umpiring. This second act had some highlights (such as umpiring in the 1942 Negro World Series), but also some low points. His umpiring career ended after an incident in 1946 in a game between the Monarchs and the Birmingham Black Barons. Tommy Sampson pushed McNair following a disagreement on a play at first base. McNair reportedly responded by pulling a knife. Sampson grabbed a bat, chased McNair, and struck his leg with a swing. McNair was ejected from the contest while Sampson remained in the game.54

McNair became a janitor upon his departure from the game, but unfortunately his retirement was a short one. On December 2, 1948, he died at his Kansas City home of cardiac failure. He was survived by his wife Emma and two adopted children.

McNair was named to J.L. Wilkinson’s all-time Negro League team in 194955 and Tom Baird’s all-time Monarchs team in 1956.56 Yet he was not listed at all on the influential 1952 Pittsburgh Courier poll that asked 31 Black Baseball players, sportswriters, and executives to name the greatest players in Negro Leagues history. In 2006, he was among 94 candidates named to the preliminary ballot for the National Baseball Hall of Fame via the Committee on African-American Baseball. He failed to make the final ballot and has not been considered for the Hall of Fame since.

The inclusion of statistical data from the Negro Leagues compiled by the Seamheads Negro Leagues database and presented on Baseball Reference has helped raise McNair’s profile with a modern audience. His all-around play made him roughly a five-win player on a 162-game basis, similar in production value to Hall of Fame outfielders Al Simmons, Vladimir Guerrero, and Kirby Puckett—a player with whom he shares both a statistical profile and physical resemblance.

Year after year, Hurley McNair hit well over .300 with patience, power, and speed, while playing excellent defense. His name rarely topped the leaderboards, but he could be spotted among the league’s best in every offensive category. By the time the Negro National League was founded in 1920 he was already past 30 years old, suggesting this dynamic, all-around performer could have been even better in his younger days (where comparatively little data exists). However, like many of his peers, McNair’s legacy remains a work in progress.

Sources and acknowledgments

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball Reference and the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database. Thank you to Gary Ashwill and Mark Aubrey for assistance with biographical information.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Kurt Blumenau and check for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Photo credits: SABR-Rucker Archive, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 “Toy Cannon” is a nickname sometimes given to players who are small but powerful. The nickname is most closely associated with Jim Wynn, an outfielder who played mostly for the Houston Astros from 1963 to 1977.

2 Larry Lester, Baseball’s First Colored World Series: The 1924 Meeting of the Hilldale Giants and Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014), 77-78.

3 “Nelson McNair, Fashionable Barber,” Marshall (Texas) Messenger, September 15, 1877: 3.

4 “The Messenger,” Marshall Messenger, February 27, 1880: 3.

5 “Nelson McNair,” Marshall Messenger, December 16, 1892: 10.

6 “Kansas City Monarchs to Tour Texas in Training Trip,” Dallas Express, March 24, 1923: 7.

7 Phil S. Dixon, Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010), 14.

8 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair,” https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Hero/322533%20Forgotten%20Heroes%20Hurley%20McNair%20Single%20Pages.pdf, The Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research, accessed March 23, 2024.

9 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

10 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

11 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

12 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

13 Dr. Layton Revel and Luis Muñoz, “‘Colored Championship’ Series,” The Center for Negro Leagues Baseball Research, https://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/RL/Colored%20Championship%20Series%20(1900-1919)%202018-04.pdf, accessed March 23, 2024.

14 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

15 Lester, 78.

16 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

17 Gary Ashwill, “Lost Island Giants,” Agate Type, https://agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2008/12/lost-island-giants.html, accessed March 23, 2024.

18 “Union Giants at Geneseo Sunday,” Davenport (Iowa) Daily Times, May 26, 1917: 21.

19 Dixon, 28.

20 Jerry Malloy, “The 25th Infantry Takes the Field,” Society for American Baseball Research, The National Pastime, Vol. 15, https://sabr.org/research/article/the-25th-infantry-regiment-takes-the-field/, accessed March 23, 2024.

21 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 541.

22 John B. Holway, Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers (Westport, Connecticut: Meckler Books, 1988), 172.

23 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2015), 53.

24 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

25 Adam Darowski, 25th Infantry Wreckers, https://darowski.com/wreckers/, accessed March 23, 2024.

26 Dixon, 29.

27 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

28 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

29 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

30 Lester, 78.

31 William F. McNeil, The California Winter League: America’s First Integrated Professional Baseball League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2002), 68.

32 McNeil, The California Winter League, 82.

33 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

34 McNeil, The California Winter League, 257.

35 Lester, 182-183.

36 McNeil, The California Winter League, 100.

37 McNeil, The California Winter League, 257.

38 Dixon, 73.

39 “Hurley McNair Back Home for Winter,” Kansas City (Missouri) Call, October 11, 1929: b1.

40 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

41 Scott Simkus, “Gilkerson’s Union Giants,” Scott Simkus, https://web.archive.org/web/20130113022716/https://scottsimkus.wordpress.com/2009/03/09/gilkersons-union-giants/, accessed March 23, 2024.

42 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

43 “Five Former Monarchs with Ark. City Nine; H. McNair is Manager,” Kansas City Call, May 26, 1933: 1B.

44 “Says Kansas Stars May Win,” Wichita (Kansas) Beacon, September 5, 1933: 18.

45 “Monarchs Crush All-Stars Here,” Wichita Beacon, September 11, 1933: 5.

46 Revel and Muñoz, “Forgotten Heroes: Hurley McNair.”

47 Dixon, 142.

48 Dixon, 144.

49 “K.C. Monarchs to Play Larks,” Hutchinson (Kansas) News, April 29, 1935: 2.

50 “Amateur Baseball Notes,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, May 7, 1935: 12.

51 “Taverns Seeking Monarchs’ Title,” Kansas City (Missouri) Journal, June 23, 1935: 11.

52 “Monarchs Cop Tiger Series Three to One,” Kansas City Call, May 28, 1937: 6.

53 “Harry Burns Hurls No-Hit Game Sunday,” Kansas City Call, July 30, 1937: a15.

54 Dixon, 181-182.

55 “Wendell Smith’s Sports Beat: This Man Believes in the Game,” Pittsburgh Courier, September 3, 1949: 22.

56 “Names of Players Sold by Monarchs,” Kansas City Call, February 10, 1956: 12.

Full Name

Allen Hurley McNair

Born

October 28, 1888 at Marshall, TX (USA)

Died

December 2, 1948 at Kansas City, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.