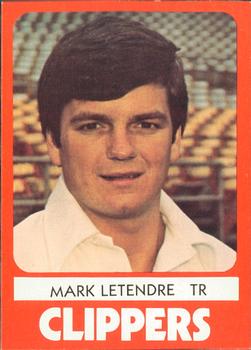

Mark Letendre

The 18-year-old student trainer was mortified. A 96-inch roll of cloth athletic tape unwound and rolled across the floor. The football team and adult training staff, along with the thunderstruck Mark Letendre, watched as eight yards of tape uncoiled. “What a rookie,” announced the Head Athletic Trainer. From that day forward Letendre was known as “Rookie.” The nickname endured through his 42-year career as a major- and minor-league trainer and MLB’s first Director of Umpire Medical Services.

The 18-year-old student trainer was mortified. A 96-inch roll of cloth athletic tape unwound and rolled across the floor. The football team and adult training staff, along with the thunderstruck Mark Letendre, watched as eight yards of tape uncoiled. “What a rookie,” announced the Head Athletic Trainer. From that day forward Letendre was known as “Rookie.” The nickname endured through his 42-year career as a major- and minor-league trainer and MLB’s first Director of Umpire Medical Services.

Mark Anthony Letendre was born on November 19, 1956 in Manchester, New Hampshire to Bertrand and Blanche (Brunelle) Letendre. Letendre’s grandparents had emigrated from Quebec, Canada. His parents were natives of Manchester, a mill and manufacturing hub and the state’s largest city. The Roman Catholic French-Canadian family owned a three-family home. Bertrand worked frequent double shifts as a loomer at the new US Velcro plant. Blanche worked as a seamstress, primarily at home while raising five children. Mark’s siblings were William (born 1946), Michel (1948), Gerald (1950), and Gloria (1959).

“We would routinely have one big meal on Sunday,” said Mark, “and then Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, were leftovers. Friday was fish and chips for Catholics. Saturday was franks and beans.” The family worshiped at St. Augustin’s Church where Letendre attended its French-speaking elementary school. After public junior high school, he enrolled in Manchester Central High School. “I was crazy for sports,” said Letendre. His favorites were baseball and basketball and he spent afternoons, evenings, and weekends at the Manchester Boys Club.1

But Letendre was small, and his November birthday made him one of the youngest in his class. At high school he said, “I could not compete to the level of my peers.” Still, “I was a gym rat all the time I had free time.”

One wise-guy moment in the gym generated an after-school detention for sophomore Letendre. He served it one afternoon while Assistant Football Coach Fred Cole was taping football players before practice. Letendre reprised but not without remarking about the teacher’s taping technique.

“You think this is easy?” said Cole. He tossed a roll of athletic tape at Letendre, who tried taping a player properly and couldn’t. “I was embarrassed I could not conquer it,” said Letendre, thinking, “I’ve really got to get good at this.”

That summer Cole found for Letendre a student athletic training camp at Northeastern University in Boston. Athletic Director H. Bink Smith requested funds from the school committee. When the board declined Smith paid the $100 registration himself. When Letendre learned about it years later he created a student athletic training scholarship in Smith’s parents’ names.2

As a junior and senior Letendre was trainer/manager for the football, basketball, and baseball teams.3 During 1973, his rising senior summer, Athletic Director Smith found another student athletic training opportunity at the University of Maine. It was run by Maine’s head athletic trainer, Wesley Jordan, Smith’s Colby College classmate.

During Letendre’s senior year at a basketball game in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Manchester Central Little Green coach suffered an attack of colitis.4 The coach was confined to the locker room, tended by medical professionals with Letendre poised at his side all the while, shuttling between the locker room and the bench. “I kept the assistant coach informed about how the coach was feeling,” said Letendre, “And the coach was able to gives pearls of wisdom to the assistant coach.”

The Little Green won the 1974 New Hampshire large high school basketball championship and played in the New England tournament in Bangor, Maine. The University of Maine’s Jordan was there. “It was a full-time rush,” said Letendre of Jordan’s recruitment pitch.

At graduation Letendre received an award from the school committee for his creative team support during the Portsmouth basketball game. He was also named “Boy of the Year” by The Boys Club for representing its mission as a member and employee through his part-time job there.

Letendre attended Maine as a Physical Education and Health major. His first student athletic trainer work was preseason football. That’s where he accidently unrolled the athletic tape and Jordan dubbed him “Rookie.”5

The University of Maine became Letendre’s full-time home. He took classes year- round while working towards his teaching certification. In the summers of 1976 and 1977 in adjacent Old Town, he was a volunteer trainer with the American Legion baseball team managed by Maine assistant baseball coach Stump Merrill.

With Letendre pursuing a baseball athletic trainer career, Jordan contacted former Maine baseball coach Jack Butterfield, Director of Player Development for the New York Yankees. The Yankees needed a trainer for their Double-A team in West Haven, Connecticut. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner wanted a certified trainer, and Letendre had started taking the required tests. “Rookie’s” accelerated academic schedule allowed him to graduate in December, so Letendre headed to spring training in March 1978. Other than three trips to Massachusetts, he had never before left Northern New England.

Twenty-one-year-old Letendre reported to the World Champion Yankees lower minor-league facility in Hollywood, Florida. As the highest-ranking trainer despite his young age, Letendre also managed the clubhouse for 100 players. That included laundry, shoe polishing, and cleaning the locker room and bathrooms. There was one familiar face, Stump Merrill, the West Haven Yankees new manager.

The first visit from demanding Yankees owner Steinbrenner was unforgettable. Assembled with his clubhouse staff, Letendre received a grilling from Steinbrenner. “So, you’re the f****** clown that runs this place?” The owner pressed, “So you’re like this is a pretty good place?” Letendre answered, “I think it is standing tall,” an expression the owner often used. Steinbrenner poked a finger in Letendre’s chest and barked, “Then why is that trash can half full?”

“It just shattered me,” Letendre recalled. Merrill reassured him, “Rookie, if you really think about it, that’s the only thing he found wrong.”

At West Haven, Letendre’s game-day routines were demanding and rigorous. Before games he would check equipment and restock supplies for pre-game work with injured players. Next, he would stretch and rub down the starting pitcher and others, update the manager on player health, record treatments, and consult with the team physician. During games he was the first responder to injuries and ensured proper follow up. After the game he treated injured and game-worn players, cleaned equipment, and updated players’ health status for the medical and player development offices. He also ran the clubhouse.

To manage responsibilities, Letendre said, “I used my hard work ethic that I had acquired from my parents,” adding “If I didn’t have an answer, I didn’t really make anything up. I’d say, ‘Just let me get back to you.’” He described himself as a “ferocious information gatherer.”

Experienced players like six-year minor-league pitcher Doug Melvin guided Letendre.6 “Those kind of players would come through and nurse me along. And after a while things became repetitive and routine,” he said. He also shared a house with 12 players. “I basically lived, breathed, and ate baseball,” said Letendre.

In 1979 the Yankees promoted Letendre to their Triple-A Columbus Clippers. Expectations were high. “George Steinbrenner wanted the 25th best major-league team at Triple-A,” said Letendre. The 22-year-old “Rookie” was also replacing a five-year incumbent, Barry Weinberg, who was named assistant trainer for the major-league Yankees.

Letendre was prepared. He had obtained his trainer certification, one of just 1,600 certified by the National Association of Athletic Trainers since 1969.7 At spring training the Clippers shared the major-league Yankees facility in Fort Lauderdale. This allowed Letendre to work with Yankee trainer Gene Monahan, then in his sixth of 39 eventual Yankees seasons. “One thing I learned from Gene,” said Letendre, “was that it’s nice to be important, but it’s more important to be nice.”

Letendre adopted the philosophy of servant leadership, which focuses on the growth and well-being of people and the communities to which they belong.8 “I always treated every player the same, whether you were the star or you were the 25th guy on the roster,” he said. On game days, though, “As we got closer to game time, the guys that were eligible for play or were going to play, they got my unfettered attention,” he said. While Letendre was younger than almost every Clipper, he had the support of manager Gene Michael, a former Yankee shortstop. To focus on player treatment full time, Letendre recruited a clubhouse manager, Tom Graney, a West Haven Yankee clubhouse colleague.

To boost player safety, Letendre assisted catcher Bruce Robinson who devised an invention that would forever change catchers’ protective gear. Robinson wanted to protect his right throwing shoulder from foul tips and errant pitches. Catchers’ chest protectors left that shoulder uncovered to avoid impeding throws. Robinson wanted to attach a flexible hinged flap to his chest protector to cover his right shoulder.

Using training room tools, shoelaces and an old chest protector, the pair fashioned the first “Robbypad.” They attached the flap to Robinson’s game chest protector. The prototype used by Robinson is now in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.9

As a trainer, Robinson said, Letendre had an “uncanny ability to command respect from the players.” The catcher said he was “supportive and protective of his players in a most caring manner.”

That fall Letendre worked in the Florida Instructional League with Pittsburgh Pirates trainer Tony Bartirome on the Yankees-Pirates co-op Bradenton team.10 From Bartirome Letendre learned a subtle way to gauge pain. “If you focus on their eyes,” said Letendre, “on the [training] table or in an emergency situation. If they’re blinking, rinsing, tearing, looking away, if the cornea is dilated, they’re telling you a story.”

In 1980 Joe Altobelli managed the Clippers. Letendre’s ability to assess on-field injuries prompted Altobelli to nickname him “Doc.” If the manager needed guidance he would ask, “What do you think, Doc?”

Letendre’s view of the game also changed. When a Clipper hit a home run and the batter returned to the dugout the trainer ignored the celebration. “The next hitter was in an injurious situation for payback,” said Letendre, so he watched the next pitch in case of a brushback or worse.

Between the 1980 and 1981 seasons, Letendre returned to his offseason job at the Franklin County (Ohio) Jail. The Clippers were one of the rare publicly owned professional sports teams in America, so other Franklin County entities were a source of non-baseball work for residents like Letendre. This was Letendre’s third winter as a medical assistant. His first year he prepared medications. The second year he assisted the dentist, whose primary task was tooth extractions. Along the way he refined what he learned from Bartirome. “I learned a lot about blinking and tearing and how to understand pain,” he said. “There was a lot of wincing and blank stares. Dealing with pain guys sometimes go to a different place.” His third year Letendre administered medication to the isolated population.

Frank Verdi managed the Clippers in 1981. The fiery Verdi sometimes needed to unwind during tense games. At Verdi’s request, Letendre added brandy to his trainer’s kit. “Doc. Doc, I have a little tickle,” Verdi would cough. The trainer would pass him his personal apothecary bottle.11

Four winning seasons in West Haven and Columbus reduced pressure in the clubhouse.12 This allowed Letendre to refine his communication skills as he evaluated player readiness for the lineup. Altobelli, seeking a “yes” or “no,” would ask, “Can he play or not play?” Letendre might respond, “I can’t give you that answer. The reason is 80 percent of this guy is better than 100 percent of his replacement.” Baseball reality was not black and white, Letendre learned, but “I knew in my heart I was giving him the truth.”

Before a game Letendre used the empty shower room for private player conferences. He’d ask: “Do you feel that if the manager played you today you would do no harm to yourself or to the team?” Most players would say: “I’m ready to go.” But, Letendre said, “Either the eyes or the hesitancy in his voice or answer would allow me to ascertain the full story.”

Letendre remembers the December 1981 phone call from Yankees Assistant General Manager Bill Bergesch promoting him to assistant trainer with New York. He replaced Weinberg, his Columbus predecessor, who had been hired by Oakland. He headed to New York with his wife of one year, Judy. “If you can make it there, you can make it anywhere,” said Letendre.

In New York, head trainer Monahan treated veteran Yankees and established players. Letendre saw lower-profile and acquired players. But one day 6-foot-6, 220-pound all-star Dave Winfield visited Letendre. “He was just too strong for me, and I was just too small,” said the 5-foot-9, 140-pound trainer, so stretching took place on the floor. “When people would come in and the first million-dollar player was on the floor with this 25-year-old getting worked on that added to my cachet.”13 Other starters followed. “I wasn’t the smartest or the most skilled, but no one ever outworked me,” said Letendre.

On September 22, 1982, the reigning AL champions were under .500, on their third manager of the season. 14 The Yankees were battling the Cleveland Indians for fifth place in the AL East. Ken Griffey Sr. was in right field. “I had been hurt and going out there every day and not complaining,” said the three-time All-Star. Rick Manning hit a double in the sixth inning that Griffey reached slower than fans expected. “There was a cascading amount of boos,” said Letendre, who realized Monahan was in the clubhouse. Fans were throwing objects at Griffey.

After checking with manager Clyde King, Letendre ran to Griffey and said, “You can stand out here and you can continue to be the tough guy that you are, but you’ve already seen what’s happened and you don’t deserve this.” Griffey walked off the field with Letendre. Going forward, the right fielder said, “Mark was the one that pushed me to make sure I did the weights and did my work, and that’s what kept me on the field.”

Over the next three years Letendre treated more Hall of Famers15 and All-Stars but was also drawn into the owner-fueled turmoil as the Yankees failed to make the postseason. In 1985 Billy Martin returned for his fourth stint as manager, assured by Steinbrenner he would stop an old habit of calling the manager in the dugout during games.

Instead, the owner had a television feed installed in the Yankees training room that Letendre was ordered to watch. Instead of calling Martin, Steinbrenner would call Letendre. He would ask a question, said Letendre. “I would go down to the dugout ask the question of Billy and then come back and give the answer.” Steinbrenner observed the process from his perch in the owner’s box.

The plan worked for one homestand. Then Martin told Monahan, “If you don’t get this f****** assistant out of here I’m going to kill him.” Letendre continued to show up at Martin’s side, but instead pantomimed speech. “I’d run up, call Steinbrenner and just make up an answer.” The workaround soon stopped, but not before the frustrated Letendre once answered the phone with, “Who the f*** is this?” and hung up. The trainer avoided Steinbrenner’s wrath by immediately delegating phone duties for the rest of the game.

On Halloween 1985, the rebuilding San Francisco Giants hired Letendre as head trainer.16 He applied Monahan’s Yankees model. “I just mimicked everything he had done right down to the [road trip] trunks,” He hired an assistant, Gregg Lynn, who later became the Cincinnati Reds head trainer.17

In the second series of 1986 at Dodger Stadium, the new head trainer was tested. “I’m working on a non-starter just before the game,” Letendre recalled. Starting left fielder Jeffrey Leonard entered the training room and announced, “Get the f*** off the table. I want to get ready for the game.” Letendre told Leonard, “I’ll finish him. I’ll get to you.” Leonard flipped over the other training table with another expletive. Letendre said, “You can leave now. This is my training room. When I’m ready for you I’ll give you a call.” Leonard quietly returned later to get stretched. In 1988 it was a sad day for both when Leonard was traded to the Brewers.

The rebuilding Giants were coming off three straight losing seasons. The bench was not deep, so there was tension between getting players onto the field and maintaining long-term health. With team doctors, said Letendre, “I constantly balanced the two.”

In 1987 San Francisco lost the NLCS to St. Louis.18 Inspired by the 1988 World Champion Dodgers’ use of an in-house physical therapist, Letendre contracted with physical therapists, massage therapists, and chiropractors. When MVP first baseman Will Clark, who lived in New Orleans, needed a trainer in 1989 the Giants hired Louisiana fitness expert Mackey Shilstone. They did the same for Matt Williams, another high draft pick.

As the complexity of his work increased, Letendre used grease boards to track treatments. “Everything was manageable as long as I stayed organized,” he said. A computer tracked the cost/benefit analysis of treatment programs and provided player health reports. When Bob Quinn became general manager in 1993, Letendre said, “The first time I met him I had a large four-inch binder full of information.”

The 1993 Giants were the first team with a training staff of three, including assistant trainer Barney Nugent and physical therapist Stan Conte. To prevent player “treatment shopping” Letendre used a phrase to cue his colleagues. When Letendre said, “Johnny Omahundro the football Cardinals trainer would do it this way,” Nugent and Conte were to follow the head trainer’s approach if they were seeking a treatment second opinion.

Across San Francisco Bay, Barry Weinberg was in the middle of his 16 years as the Athletics’ head trainer. “Mark was the type of guy who wanted to learn, he had a thirst for knowledge and had passion for what he did,” said Weinberg. “He had a personality that helped him get along with players and staff.” Eventually, said Weinberg, “I called him ‘Commish’ because he was such a go-getter. I thought he’d be Commissioner [of baseball] one day.”

Although performance-enhancing drugs cast a shadow over baseball during in the mid-1990s, Letendre noted that they were not banned by baseball. Despite clubhouse murmurs about PEDs, said Letendre, “Medical staffs were not in the position to be enforcers.” The daily priority was preparing for games.

When Giants players needed enhanced protective gear, Letendre added a removable flap to Kevin Mitchell’s shin guard. Barry Bonds nearly had his right elbow broken by a pitch so Letendre helped design a dual-purpose elbow pad. It shielded the joint and also discouraged Bonds from overextending his swing and chasing pitches off the plate.

With MVP Bonds, the Giants won 103 games in 1993 but finished second in the NL West.19 The next three years the team finished under .500. The front office said the Giants suffered because medical services weren’t fully coordinated. Letendre absorbed some of the criticism, even though outside the training room he was a medical colleague, not a supervisor.

Nevertheless, he proposed to Quinn, “Give me control and if we have the same results I won’t even come upstairs [for an annual review]. I’ll just go home.” As Director of Medical Services, he coordinated health services for the entire Giants organization. Led by Bonds and Jeff Kent, the Giants won the NL West in 1997 and finished second in 1998 and 1999.

In 2000 Major League Baseball became the first professional league to provide medical services for its officials, hiring Letendre as its Director of Umpire Medical Services. “We didn’t have anything formal prior to that,” said Larry Young. Young was an umpire for 25 years beginning in 1983, then continued with MLB in 2008 as an umpire supervisor (a position he still held as of this writing in 2022). Injured umpires relied on team trainers for medical oversight. For umpires it was joints that suffered the most — knees, back, hips and neck. “All those things would break down eventually,” said Young.

The umpires’ preseason physical was “an executive physical that was not germane to umpiring,” said Letendre. “Perception had become that umpires were fat and out of shape, and therefore missing calls,” he said.20 Three years earlier NL umpire John McSherry, 51, who was seriously overweight, collapsed and died of a heart attack on the field on Opening Day 1996.

This was more than a culture change job, Weinberg noted, “There’s no groundwork. There’s no protocol to what you do. You have to create it yourself.” And with no home ballparks, he said, each four-person crew was on the road 100% of the time. “You have 15 teams in 15 towns.”21

Letendre was curious about umpiring demands so he met with firefighters and police officers in Scottsdale, Arizona where he lived. 22 Firefighters, like umpires, transition from a static state to dynamic movement. Police officers, like umpires, enforce rules under pressure.

The 2000 season for MLB’s 68 umpires began with spring training pre-employment physicals in Florida and Arizona.23 Letendre added dental, oral health, and enhanced vision screening. Oral health included the anti-spit tobacco project he started in the late 1980s with the Professional Baseball Athletic Trainers Society. “He got a lot of people to throw tins of smokeless tobacco, dip and chew into the waste basket,” said Young.

Scottsdale, 12 miles from Phoenix, was the hub of Umpire Medical Services. MLB’s Umpiring Vice President Ralph Nelson lived there, as did Letendre with his wife and two daughters. Nelson and Letendre met with umpires when they traveled to Chase Field for Diamondbacks games. New Orleans-based trainer Shilstone oversaw performance enhancement. Letendre rotated through all 30 stadiums to meet athletic trainers and ensure attendants were properly stocking umpire rooms. He educated and advocated. “I never in 20 years mandated anything,” he said.

Letendre graded the first year a “C.” “We’re a suspicious lot, kind of paranoid,” said Young. “Some people were saying here comes a guy and he’s going to be the reason why some guys are let go.” Some older umpires did not adjust how they managed stress, said Letendre. “The two biggest stress relievers are alcohol and food.”

In 2001 the program added a medical consultant, Dr. Steven Erickson. Two years later psychologist Ray Karesky started a wellness program. Umpires were encouraged to stay in hotels that had full fitness centers. Letendre created city-to-city care continuity led by the home team training staff. Weinberg was head trainer for St. Louis through 2011. “You could get a call or a note from Mark saying someone is,arriving who got hit with a ball. Please check them,” said Weinberg. “Or they’re fighting the flu, or can you find a doctor for him to see when he gets there.” Weinberg would then share updates with Letendre.

“It was combination of diet and exercise that he put together specifically for our profession,” said Young. Programs were later personalized based on individual physical profiles. Healthy restaurant directories were created. Preseason preparation expanded to two days for on-field topics and two days of physical exams and health awareness sessions.

By 2004 umpires had become fans of Umpire Medical Services. “You wouldn’t believe the difference in the size of the uniforms from four years ago. We have a multitude of umpires who request smaller belts,” Letendre observed.24

Letendre viewed the umpires as the 31st major-league team, so he developed a player-like return-to-work program. After long layoffs, umpires worked with Shilstone in New Orleans. “You would start out doing exercises that pertain to your injury, and then you would work minor-league games in New Orleans,” said Young. “You could tell if you were ready to go back to the big stage. Before that I think there was always doubt in your mind.”

Squatting behind home plate was no longer a grind to be quietly endured. Beginning in 2003, MLB created an annual “Squats Crown,” with Jeff Nelson the first “king.” The highest season total was 11,570 by Chuck Meriwether in 2004. In 2019 leader Dan Iassogna averaged 323 squats per game in his 33 home-plate assignments.25

To mimic game conditions, the pre-employment physical added on-field movements including repetitive squats, sprinting from the outfield to the infield, and moving between bases. For concussion management, there was baseline cognitive, vestibular, and ocular testing. For home plate umpires, protective shoes were updated, and a modified hockey goalie head bucket was developed. It had more vents for air circulation, larger ear holes for sound detection and enhanced energy absorption. Sunglass options were expanded to match different sky conditions. Cooling packs were used for heat management.

As baseball evolved, there were more demands. Eight additional umpires were hired in 2014 for expanded replay monitoring.26 Average game length broke the three-hour barrier. While postgame lifestyles improved with healthy meals and reduced alcohol, a new distraction emerged, said Letendre. Video games became a threat to relaxation. “They’re going back [to their hotel room] to compete,” said Letendre. Umpires were cautioned that video games raised heart, brain, and hormone activity and could undo their postgame relaxation work.

New and veteran umpires praised Letendre’s program. Cory Blaser, a 2014 MLB hire, said, “If you have a head blow, if you take a foul ball off the mask, you have a text message before you even get off the field, and you have to call and check in.” Paul Schrieber, a 19-year veteran who retired in 2015 said, “He’s an amazing resource for us. Anything you call him about – anything – he’s on top of it.” 27

Umpire Medical Services became more than medical care. “It became a labor of love for me,” said Letendre. “I was able to see a side of them that’s human, which the fans and major-league baseball don’t see, which is how much pride they take in their job, and how they live with a call that they missed.”

Health awareness also occurred off the field. In 2015, Young attended a meeting in New York. Letendre saw the umpire supervisor and said, “What’s the matter with you? You look terrible.” He noticed that Young’s skin and eyes were yellow. When Young mentioned that his urine was discolored, Letendre arranged for an MRI the next day. The symptoms were caused by early-stage pancreatic cancer. After prompt treatment, Young became cancer-free. “If Mark hadn’t recognized those signs, things would have turned out a lot differently,” said Young.

Over 20 years there were painful moments. Letendre relentlessly encouraged one umpire and his wife to aggressively manage his chronic condition. Those efforts were waved off. It wasn’t until the umpire had disfiguring surgery that his wife called to apologize, finally understanding “all I was trying to do was save his life,” said Letendre. “That was very humbling.” The passing of two active umpires hit hard. They were Wally Bell, 48, in 2013 of a heart attack a week after working the NLDS and Eric Cooper, 52, in 2019 of a post-surgical blood clot two weeks after working the ALDS.

Over his 20-year Umpire Medical Services career, Letendre was pleased with umpires’ fewer missed days, faster return to the field, and their appearance. “Before you would have probably three out of four umpires out of shape and less than athletic looking. Now, you probably have a half a dozen out of the 76,” he said.

There were also better health, longer careers, and improved quality of life after retirement. Looking back, said Young, “Everybody in my generation has some kind of knee, back, or hip problem and we owe the longevity of our careers to a large point to Mark. He got us into rehab. He got us into surgery.” In 2001, only four of 68 umpires were over 55, although that number may have been suppressed by the mandatory age-55 retirement required into the 1980s. In 2019, 19 of MLB’s 76 umpires were over 55.28

Letendre retired in 2019, the year after his induction into the University of Maine Sports Hall of Fame, his third Hall of Fame induction.29 “I was as successful in my career as an aggregation of the staff that I was able to pull together,” he said. In 2020 Letendre was an advisor to Umpire Medical Services and that year was inducted into the National Athletic Trainers Association Hall of Fame.30

Last revised: April 14, 2022

Acknowledgments

This article was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Joe DeSantis and checked for accuracy by SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted all quotations, observations and by and about Mark Letendre were obtained and concluded from telephone interviews, electronic messages noted below, and endnote sources.

Personal Interviews and Correspondence

Mark Letendre, telephone interviews, January 12 and 17, 2022; also emails and text messages

Ken Griffey, Sr., telephone interview, February 10, 2022

Larry Young, telephone interview, February 24, 2022

Barry Weinberg, telephone interview, February 28, 2022

Bruce Robinson, email, February 18, 2022

Notes

1 As of 1983 it became known as the Boys and Girls Club of Manchester.

2 The Bertrand & Blanche Letendre Memorial Summer Athletic Training Camp Scholarship was created in 2006. It is offered through the New Hampshire Musculoskeletal Institute of Manchester.

3 Letendre was the baseball team’s student manager in his sophomore year, 1972.

4 Manchester Central High School took the name Little Green for its sports teams from Dartmouth College’s sports teams the Big Green. Dartmouth is located in Hanover, NH 75 miles northwest of Manchester.

5 Both Jordan and Letendre have awards in their name at the University of Maine. The Mark A. “Rookie” Letendre award was created in 1991, presented to the outstanding student trainer who best reflects the ideals, dedication, loyalty, and commitment to the athletic training profession and the University of Maine. Jordan retired in 1997, the first year of the Wesley D. Jordan Athletic Service Award, recognizing outstanding dedication, loyalty, and perseverance in the name of Maine athletics.

6 Doug Melvin retired after the 1978 season with a career minor-league record of 29-19 and an ERA of 3.43 in 128 games as a starter and reliever. From 1983 to 1993 he worked in the front office for the Yankees and Orioles. From 1994 to 2001 he was the General Manager for the Texas Rangers. For the next 13 years he was President of Baseball Operations and General Manager of the Milwaukee Brewers.

7 “Milestones in Athletic Trainer Certification,” Journal of Athletic Training, July-September, 1999, Paul Grace page 287 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1322924/?page=3

8 https://www.greenleaf.org/what-is-servant-leadership/. While traditional leadership generally involves the accumulation and exercise of power by one at the “top of the pyramid,” servant leadership is different. The servant-leader shares power, puts the needs of others first, and helps people develop and perform as highly as possible.

9 Background and history about the Robbypad can be found at Baseball By the Sea Media. https://sites.google.com/view/baseballbythesea/home/the-robbypad.

10 Letendre said the Pirates could not afford its own Instructional League team, so the Yankees had some players play for Pittsburgh’s Bradenton team. Bartirome is believed to be the only person in major-league baseball history to have participated as a player, trainer, and coach at the major-league level.

https://thebradentontimes.com/bradenton-man-who-was-longtime-pirates-trainer-passes-p19965-158.htm.

11 Verdi’s minor-league playing and managerial career spanned 50 years, with over 5,000 games as a player and manager. His 1981 season as Clippers manager, and his occasional in-game alcoholic sips, is covered in the book Almost Yankees: The Summer of ’81 and the Greatest Baseball Team You’ve Never Heard Of, by J. David Herman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2019).

12 West Haven had the best overall record in the Eastern League in 1978 at 82-57 but finished in second place in both halves of the split season and did not qualify for the playoffs. The Clippers finished in first place in 1979, 1980 and 1981 and won the International League playoffs each year, becoming the first Triple-A team to accomplish this dual feat. They were a combined 94 games over .500. In 1979 65 percent of the players were prior or future major leaguers; in 1980 76 percent; and in 1981 71 percent.

13 Winfield’s multimillion dollar Yankee contract was actually signed following the 1980 season, about a year after Nolan Ryan signed a four-year $4.5 million per year free agent contract with the Houston Astros.

14 Managers for the 1982 Yankees were Bob Lemon (14 games), Gene Michael (86 games), and Clyde King (62 games).

15 Hall of Famers on the Yankees during Letendre’s time with team were Phil Niekro, Rickey Henderson, Dave Winfield, and Goose Gossage.

16 Al Rosen, who was Yankees president for 18 months through July 1979, became the Giants General Manager in 1985. That was the second consecutive year the Giants finished last in NL West. Rosen offered the position to Gene Monahan first, but when Monahan declined, Rosen offered the job to Letendre.

17 Lynn was a Double-A trainer in 1984. He was the Giants assistant trainer until 1992. He the Cincinnati Reds head trainer from 1993 to 2002.

18 In 1997 Letendre was selected as a trainer for the National League All-Star team, a recognition repeated in 1994.

19 Clark, Williams, Bonds, and Robby Thompson led the offense. Bill Swift (21 wins), John Burkett (22 wins) and Rod Beck (48 saves) led the pitching staff.

20 “Major League umpires getting help from trainer Mackie Shilstone,” East Jefferson General Hospital News, [undated] https://ejgh.org/major-league-umpires-getting-help-from-trainer-mackie-shilstone/.

21 In 2001 there were 17 umpire crews, according to the 2001 MLB Umpire Media Guide.

22 Letendre was actively involved in Scottsdale civic and non-profit groups, including the Boys and Girls Club of Scottsdale and the Scottsdale Charros, an all-volunteer, nonprofit group of business and civic leaders supporting youth sports, education, and charitable causes. In 2000, while attending a Diamondbacks game, he was invited by Joe Garagiola, Sr., then an Arizona television broadcaster, to join the Baseball Assistance Team. B.A.T confidentially helps members of the baseball family in need of assistance. In 2022, Letendre was B.A.T. Vice President.

23 Previously umpires flew to New York City during the winter for physicals. Letendre calculated that the process was more expensive and sometimes physicals were delayed due to weather-related flight delays. By holding the physical exams as part of pre-spring training activity they could be expanded and combined with other professional development activities over several days.

24 Barry M. Bloom, “Umpires benefit from medical policy,” MLB.com, February 9, 2004.

25 2014 and 2020 MLB Umpire Media Guides http://www.stevetheump.com/reports/2020%20Umpire%20Media%20Guide.pdf

http://www.stevetheump.com/reports/2014_Umpire_Media_Guide.pdf

26 There were about 80 reviews per year from 2009-2013. When replay expanded in 2014 the annual average through 2019 was 313. http://www.stevetheump.com/reports/2020%20Umpire%20Media%20Guide.pdf.

27 Bill Nowlin, Working a “Perfect” Game — Conversations with Umpires (South Orange, New Jersey: Summer Game Books, 2020). Quotes taken from an MS Word file of the book provided by the author. (Page numbers do not correspond to the published version.) Chapter 5 “Laz Diaz, Chris Guccione, Cory Blaser, and Clint Fagan” and Chapter 15 “Fieldin Culbreth, Jim Reynolds, and Paul Schrieber.” Schrieber passed away in 2020 of a cerebral brain hemorrhage.

28 This information was obtained from umpire profiles in 2001 and 2020 Umpire Media Guide released by MLB. The 2020 media guide is available at http://www.stevetheump.com/reports/2020%20Umpire%20Media%20Guide.pdf. The 2001 media guide was temporarily loaned to the author by Mark Letendre.

29 He was inducted into the Manchester Central High School Hall of Fame in 2006 https://central.mansd.org/our-school/hall-of-fame and the Boys and Girls Club of Manchester Hall of Fame in 2011 https://www.mbgcnh.org/hall-of-fame-inductees.

30 Other career recognitions included: National Athletic Trainers Association, Most Distinguished Athletic Trainer, 2010; Professional Baseball Athletic Trainers Society, President’s Distinguished Service Award, 2011; Outstanding Alumni Award, University of Maine, 2014; Visionary Award, Professional Baseball Chiropractic Society, 2015.

Full Name

Mark Anthony Letendre

Born

November 19, 1956 at Manchester, NH (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.