Sherry Smith

Sherry Smith was a laconic Georgian who narrowly lost a World Series game to the young Bambino, fashioned a long mound career despite missing a season as a doughboy during World War I, and later nabbed small-town scofflaws as efficiently as he had baserunners who’d strayed too far off the first sack.

Sherry Smith was a laconic Georgian who narrowly lost a World Series game to the young Bambino, fashioned a long mound career despite missing a season as a doughboy during World War I, and later nabbed small-town scofflaws as efficiently as he had baserunners who’d strayed too far off the first sack.

Sherrod Malone Smith was born at Monticello, Georgia, on February 18, 1891, the sixth of eight children in the farming family of Henry and Zipora Smith. “They say daddy learned how to pitch throwing balls of cotton at rabbits in the cottonfields,” his daughter recalled nearly a century later. “I used to say, ‘Daddy, how about that story’ and he’d just laugh — he was a man of very few words, but knowing him it was probably true.”1

Reared and educated in Mansfield, Georgia, which he considered his hometown, Smith played football, basketball, and “in baseball, he could do anything but make the ball sit up and bark.”2 After finishing his schooling in 1909 he played town ball in Elberton, Madison, Monticello, Newborn, Mansfield, and Athens, all situated east of Atlanta.

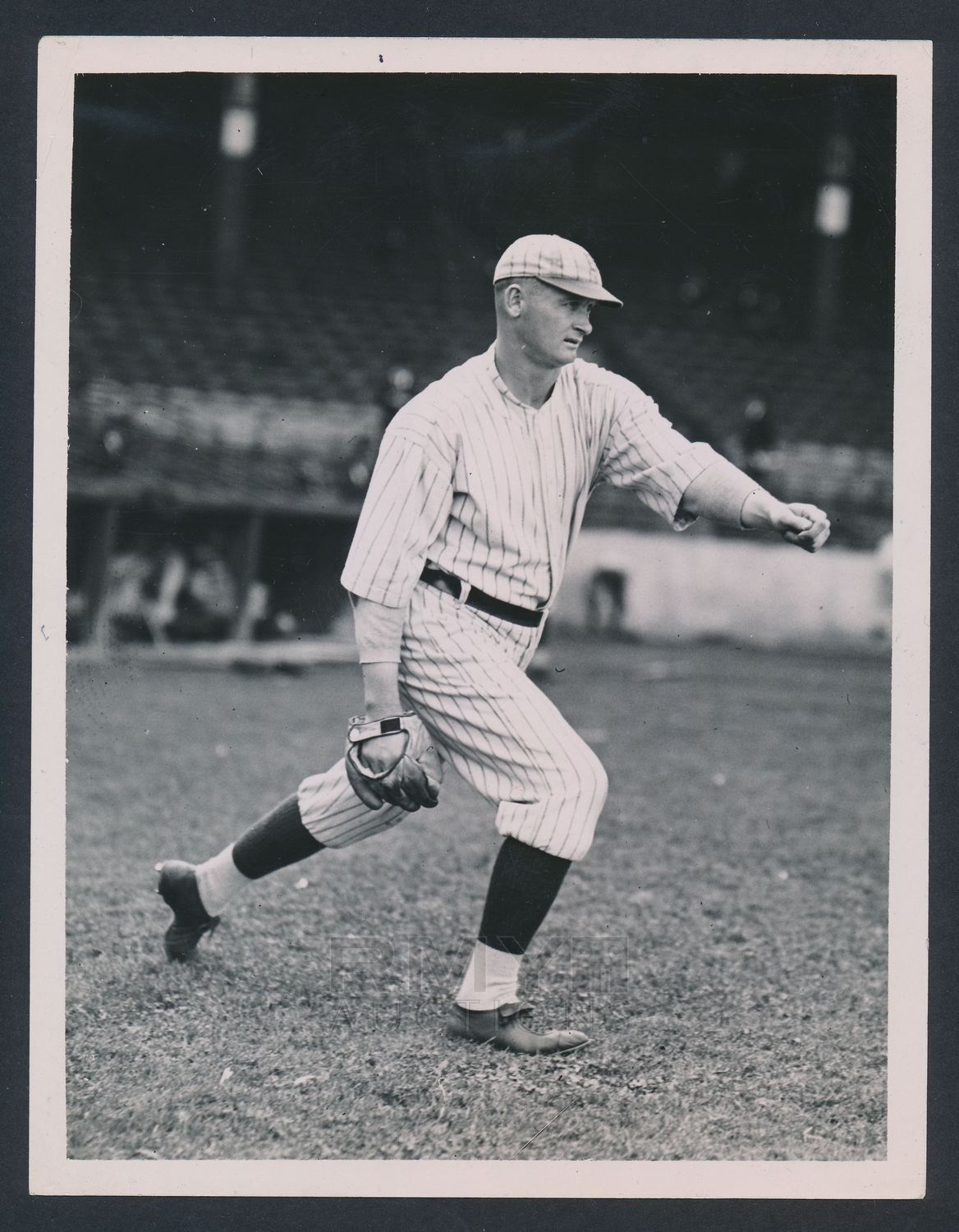

A side-arm left-hander, Smith broke into professional ball in May 1910 during a short stint with the Greensboro Champs in the Class D Carolina Association. He was a beanpole, an inch over 6 feet and 165 pounds, but steadily filled out during his career, sportswriters often commenting on his imposing size. “Somebody has said that lefthanders don’t have control — we guess it is so, and that Smith is just the exception to the rule — certainly he had his eyes focused on the center of the plate yesterday,” a Greensboro newspaper said after his sole victory there.3 Ten days later the club released him after a poor outing, local articles showing a record of 1-2 in four games.

Smith briefly returned to town ball before catching on with the Jacksonville Jays of the Class C South Atlantic League in August. He gained attention in Florida by throwing a complete-game shutout over the Augusta Tourists. “Only 29 visiting players came to the plate during the entire game and the southpaw’s control was perfect as he did not pass a man.”4 Often playing at third base when not pitching, the young lefty ended his month in Jacksonville with a record of 2-0-1. The Pittsburgh Pirates noticed and picked up his contract that winter.

Shenanigans by Jacksonville nearly cost Smith his big chance. The club told Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss the southpaw was sick, had been released, and was recuperating somewhere along the Gulf Coast. The magnate grew suspicious and started an investigation. “This resulted in the discovery that the Jacksonville club had tried an old trick and had signed Smith for the season of 1911,” the Pittsburg Press reported.5 Jacksonville lost its claim both to the pitcher and to his draft money, which went to the South Atlantic League.

“I helped the Jax in their attempt to cover me up,” Smith admitted. “I am only 20 years old, and I feared I would not make good if I jumped into the big league right away, so I agreed not to answer letters from the Pittsburgh club. However, I finally got a registered letter, and had to respond.”6 Dreyfuss sent him train fare to join the team and made sure he used it.

The left-hander stuck briefly with Pittsburgh, the youngest player on the roster. He debuted in relief on May 11, 1911, as the Pirates were getting drubbed by Pete Alexander in Philadelphia. The game saw multiple Pittsburgh ejections, Honus Wagner getting the heave either through mistaken identity or for laughing at the guilty party, Dots Miller, who had played with the umpire’s whisk broom. Wagner wandered out to help Smith warm up. A fan in the bleachers began razzing the rookie as he worked.

“Smith is a hot-blooded southerner, and refused to stand for talk from a colored gentleman,” a Pittsburgh newspaper said.7 The Georgian fired a baseball at his tormenter and missed. The fan retaliated with a soda bottle that also missed. “A big copper thereupon landed on the offending negro and sent him to the police station.”8 Smith certainly had a temper, and photos often showed him wearing an intimidating glower, but the ugly confrontation wasn’t typical. No similar incident with a fan of any race emerged later during his career.

The southpaw entered the blowout in the eighth inning with a runner on third after three Phillies already had scored. “It was the Mississippian’s [sic] first appearance in a big league game and the situation was too shaky to calm his nerves. Smithy was swatted four times before he succeeded in getting the side retired.”9 The Pirates lost 19-10, Alexander going the distance during Smith’s sole big-league appearance of 1911.

The Pirates sent the youngster the next month to manager Joe Cantillon’s Minneapolis Millers in the Class A American Association. “Sherrod Smith had everything except experience,” Dreyfuss explained.10 A Minneapolis newspaper reported, “He is big and strong, has wonderful control for a southpaw and appears to possess every requisite for a star.”11 Appearing both as a starter and in relief, Smith had a 1-2 record with eight appearances when the Millers released him in July to the Cotton States League.12

“Smith looked to be a good pitcher … and great things were predicted for him,” the Minneapolis Tribune said, “but he has been hit hard in nearly every game in which he has participated, failing to deliver the goods.”13 The southpaw performed better in Class D, winning his first three starts for the Greenwood Scouts in Mississippi. He was 9-4 in mid-August when Pittsburgh ordered him to finish the year with the Class B Fort Worth Panthers. A leg injury, however, ended his season before he could head for the Texas League.

The pitcher spent 1912 with the Springfield Reapers in the Class B Central League, going 18-16. “Smith has been pitching good ball and is not wholly to blame for the number of defeats credited to him,” a newspaper said. “In a number of the games it was the failure of his team mates to hit that lost the contests by narrow margins.”14 Smith returned to Pittsburgh after the minor-league season ended and pitched three times in relief, including both ends of a doubleheader.

Still unable to stick permanently with the Pittsburgh team, Smith began 1913 with the Louisville Colonels back in the American Association. He began well but after a “little incident” with his manager was shipped out to the Grand Rapids Bill-eds, again in the Central League, “where his work virtually won the flag for the Grand Rapids club.”15

Scout Larry Sutton signed Smith for Charles Ebbets Jr.’s International League club at Newark. Sutton also nabbed his main objective, Smith’s teammate pitcher Jeff Pfeffer, a coup he called his “daily double.”16 Sutton considered Smith something of an iron man. “The ‘Old Scout’ tells how ‘Sherry’ Smith pitched three and four times a week, and stood the strain like a southpaw Joe McGinnity.”17

Smith had an offer from the new Federal League but signed with Newark, where he intended to make good. “If ever there was one who is working to land a job here with Newark, it is this youngster,” the Newark Evening Star said. “Sherrod has a ball in his hand from the moment he appears on the ball field until [player-manager] Harry Smith gives the orders to hike for the hotel.”18

The hurler started the season with a lingering sore arm he attributed to throwing too long during a spring-training outing against the Yankees. “Sherrod Smith is a persistent victim of the thing they call the ‘jinx’ this season,” the Star said after a 1-0 loss in June.19 Smith overall posted an 8-12 record in 23 appearances, but a former teammate put in a good word for him. “Pitcher Edward J. Pfeffer of the Brooklyn Club was with Smith on the Grand Rapids Club in 1913, says he will make a good pitcher and strongly recommends him.”20 Charles Ebbets Sr. signed Smith that winter for the Brooklyn Dodgers, the Georgian’s 10th professional team.

Smith hit the ground running for manager Wilbert Robinson — while keeping opponents from literally doing the same. An Atlanta writer noted that the left-hander “led the National league in snagging men off first base in1915, his first year in the big show. He had a total of 15 victims.”21 Two decades later Smith was “still looked upon as having possessed the most deceptive move to first base that any pitcher ever had.”22 Smith’s daughter later recalled, “Dad used to say he would purposely walk a batter just so he could pick him off.”23

He remained almost seven full seasons with the Dodgers and pitched three complete games during two World Series. Smith is best remembered for the first, an extra-inning classic in 1916 vs. the Boston Red Sox. His opponent was pitcher Babe Ruth, who later called their October 9 encounter “one of the greatest World Series battles ever put into the book.”24

Played at Braves Field rather than Fenway Park, Game Two was a compelling duel between the two young hurlers. “Smith might have won his own game but for a bit of foolish base running in the third inning, when he tried to stretch a double into a three base hit,” the New York Sun observed.25 Both starters were still in the game at the bottom of the 14th inning with the score tied 1-1 and “gray shadows creeping down over the stands to the playing field.”26

“Sherrod Smith, the Georgia shrapnel, pitched his arm off and his heart out in a heroic effort to hold his hard pressed mates in the fight,” sportswriter Grantland Rice wrote.27 Dick Hoblitzell reached second on a walk and a bunt and Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan sent speedy Mike McNally in to run for him. With Minooka Mike running on contact, pinch-hitter Del Gainer sliced a liner between third and short. Zack Wheat scooped up the ball in left and fired home, but “McNally went over the plate like a hound after a fox and the game was over.”28

“It’s tough, it’s tough! After all them endeavors, deed ’tis,” Boston Globe cartoonist Wallace Goldsmith drew Smith saying mournfully on the mound.29 “Sherrod M. Smith never pitched a more brilliant game in his life, and he showed to far better advantage than the vaunted Babe Ruth,” the New York Tribune declared.30

Smith went 28-18 during his first two full seasons in the majors. After America entered World War I the following April, he dutifully registered for the draft and was among the first major leaguers summoned into service after finishing the 1917 season with a 12-12 record. The Georgian reported to the Army that December at Camp Gordon, north of Atlanta.

White Sox backup catcher Joe Jenkins also trained at the camp. Photos of the pair, each striking a baseball pose in his khaki uniform without a glove or other gear, ran together in newspapers across the country. “Having been originally drafted from the minor leagues to the majors, and then drafted from the majors to the Army, the battery has been drafted into the series of intercantonment games for the championship of Uncle Sam’s fighting forces at home and abroad,” one paper reported, although the series never happened.31

In March 1918 the hurler-turned-doughboy sailed for France, where the Army assigned him to a front-line unit, the 102nd Field Artillery Regiment. But Smith wasn’t an artilleryman and instead served mostly on detached duty in Paris as a military policeman. Unlike many ballplayers in the service, Smith maintained little contact with his ballclub back home. “Less has been heard about him than about any other Brooklyn player who went abroad,” the Brooklyn Eagle observed, adding that “the masterly inactivity of S. Smith as regards pitching and trying out his good left wing is puzzling sharps.”32

Promoted to supply sergeant, Smith pitched at least twice in rear areas while overseas. The first time was in a “hotly contested game” against an Army team boasting several former minor leaguers, which he lost.33 Another strong doughboy team “hammered him all over the lot” in a second game, chasing him after at the end of the fifth inning.34 After returning to America in April 1919, Smith pitched in a third game for the 26th “Yankee” Division at Camp Devens, outside Boston, his team winning the five-inning contest. “Sherrod Smith, the former Brooklyn National leaguer, was in the box for the divisioners for two innings, giving way to Lieutenant [Shorty] Des Jardien, the Cleveland American league twirler.”35

The ex-MP returned to Brooklyn after his discharge, sportswriter Rice speculating that he “would just as soon pitch three or four hours a week as to officiate eight hours a day as an MP in France.”36 Despite winning his first game, the southpaw experienced his first losing season with the Dodgers. As with Alexander of the Cubs, Ernie Shore of the Yankees, and other players returned from the armed forces, Smith’s performance declined from prewar levels. “If you are going to play good baseball you have got to play baseball all the time,” he said. “I came out of the army feeling like a two-year-old, but it took me half the summer to make the old ball behave rightly.”37

That winter, on his 29th birthday, Smith wed Addilu Ozburn of Mansfield, Georgia, who had turned 22 three days earlier. Her family would recall her as “an accomplished pianist who attended the Juilliard School of Music in New York City,” although whether this was before her marriage or while Smith pitched in Brooklyn is unclear.38 The couple had two children, Sara and Sherrod Jr.

The newlywed hurler regained a winning record (11-9) in 1920 and returned that fall to the World Series, pitching twice for the Dodgers against Tris Speaker’s Cleveland Indians. Smith first faced Ray Caldwell in Game Three at home on October 7 with the series tied 1-1. Caldwell lasted one-third of an inning, giving up the only runs Brooklyn needed. Smith pitched the complete game to win by the old familiar score, 2-1.

“It was Sherrod Smith, the massive left-hander, who let Cleveland down with three scattered blows, but outside of his pitching Smith had no chance to lose with a supporting cast that swarmed all over the field for everything in sight,” Rice wrote in the New York Tribune.39 The Indians “did not merely dislike Smith’s left handed offerings,” the New York Herald added. “They positively hated them.”40

The Dodgers dropped the next two rounds to enter Game Six trailing 3 games to 2 in the best-of-nine-games series. Smith took the ball October 11 in Cleveland versus former Dodger Walter “Duster” Mails, who had tossed 6⅔ scoreless innings in relief during Game Three. The Georgian was again brilliant, surrendering only one run when Speaker singled in the sixth inning and scored on George Burns’ double. But the Dodgers were harmless behind Smith and the run held up for a 1-0 victory by Cleveland, which took the series in Game Seven.

“Sherrod Smith fell heir to a hopeless enterprise in his second start,” Rice wrote. “If he had shut out the Indians for a dozen innings the best he would have drawn was a tie. He never had a chance to win with Mails breaking up the Brooklyn attack as if it was made of dry cedar.”41 The left-hander “still possesses his hurling brilliancy,” a Cleveland scribe wrote. “He was at his best yesterday. He delivered the best brand of pitching of all of the Brooklyn pitchers during the series.”42

Smith never again reached the World Series. He was 1-2 over his three complete games, during which he surrendered three runs over 30⅓ innings for an ERA of 0.89. The hard-luck lefty played two more seasons for Brooklyn before the Indians claimed him off waivers in September 1922. Owner Ebbets was exceptionally gracious in letting him go.

“From the day he joined the team at the training camp in 1915 he has been a man who played to win, and was at all times willing to give his best services in any direction,” Ebbets said. Smith had never complained about becoming a relief pitcher. “On the contrary he has ever been willing to sacrifice himself in the interest of winning games. That class of man is a credit to the sport and a credit to himself.” Smith’s record in Brooklyn was 69-70 with 18 saves. Ebbets hoped that in new surroundings and a different league, “he may prolong his major career several years.”43

Smith did exactly that. He appeared in two games for the Indians that year followed by another five full seasons, ultimately going 45-49 in Cleveland with four saves. He said later that his best experience in baseball came on August 9, 1925, when he defeated the Senators in Washington on the day his son was born. “Smith declares … that becoming a ‘papa’ and beating Walter Johnson in the same afternoon afforded him the biggest thrill in 15 years in the major leagues.”44

While playing in the American League he became good friends with pitcher-turned-slugger Ruth, who often dropped by for Addilu’s home cooking when the Yankees visited Cleveland. “Babe when he came to our home — he brought me what looked like a ton of lollypops,” Smith’s daughter remembered. “And he always wanted my mom to cook country ham and redeye gravy.”45

Smith filled multiple roles while in Cleveland. In 1926 he “was a great help to the Indians because of his ability to steal the pitching signs” and tip off batters, the Cleveland Plain Dealer said. But opponents caught on, and in 1927 “he was used almost exclusively as a coacher at third base and a coach of the young pitchers.”46 Smith’s long run in “The Show” ended with his unconditional release the first week of 1928. His major-league record after 14 seasons was 114-118, with 23 saves.

Sportswriters thought he might next try managing. Smith did so, but without entirely abandoning the mound. He went back to Georgia and caught on with the Southern Association Atlanta Crackers as a player, unofficial pitching coach, and occasional substitute for manager Bert Niehoff. “I want to help all these youngsters as much as I can,” he said of coaching. “Fifteen years in the majors can teach you something, anyhow.”47

Smith weighed 200 pounds and had slowed with age. A local sports cartoonist cracked in a caption that he had been “throwing baseballs left handed for the last 64 years.”48 Smith became an effective pinch-hitter, once swatting a triple, but did little to help himself on the mound. He went 0-4 in seven appearances as a starter and spot reliever during the opening weeks of the 1928 season. “If Sherry continued to hurl baseballs from now on he might win a ball game, but even such a charitable statement as that is doubtful,” a sportswriter wrote shortly before Smith’s release.49

Competition was easier down in Class D ball. The first week of August the left-hander took over as player-manager of the Cedartown (Georgia) Sea Cows in the Georgia-Alabama League. Smith kept pitching, often in relief, for Cedartown and for every club he managed afterward, finishing the season there with a 4-1 record. He stayed with Cedartown through the 1930 season, still taking the mound.

“If there’s anything Talladega fans like better than humbling the Cedartown outfit, it is licking them when the portly Sherrod Smith is in the box,” an Alabama newspaper crowed in 1930.50 Smith went 14-2 during 20 games that season to lead the league. “His own splendid pitching was mainly the reason for the pennant going to the Cedartown club.”51

The following season Smith took over the Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners in the Palmetto League, a Class D circuit that proved to be a “weak swimmer in a turbulent sea.”52 The league folded in late July as the Depression deepened, a local newspaper editorializing that “this year the baseball fan has not had the wherewithal to support his family and the game.”53

Smith next was named player-manager for the 1932 Macon (Georgia) Peaches in the Southeastern League, where he still pitched occasionally. The Class B league also folded, in mid-May, another victim of plummeting attendance. Smith soon began managing the Tallahassee Capitals in the semipro Georgia-Florida League, but was released within a month when the club couldn’t afford his salary. Smith’s long baseball career ended there.

A newspaper had once called Smith the “scion of a wealthy southern family.”54 It was an exaggeration, but even recently the Atlanta Constitution had labeled him “a prosperous planter of Mansfield, Ga., and who, by his own statement, has everything on his farm but a collection of white mice.”55 With the economy in tatters and baseball behind him, however, the former hurler needed a job. Looking back his Army days as an MP, he began a new career as a lawman.

Smith first became chief of police at Porterdale, Georgia, and sheriff of surrounding Newton County. Later he was captain of the guard at Tattnall State Prison in Reidsville. During World War II the southpaw worked as sergeant of the guard force at the Southeastern shipyard in Savannah. “He looks grand and to tell you the truth I wouldn’t like for him to turn one loose with that left hand right now,” Addilu wrote to an inquisitive sportswriter.56

The town of Madison, Georgia, appointed Smith its chief of police in November 1945, following the murder of his predecessor. Like Andy Taylor’s sheriff’s department in Mayberry, the force had one patrol car, which the chief used to pull over former football coach Harry Mehre for speeding. “Coach Mehre told him that he didn’t realize who he was, that he was the former coach of the Georgia Bulldogs,” a resident remembered. “Chief Smith replied, he didn’t care if he was the King of England and issued him a ticket.”57

The southpaw served as chief for exactly three years, until his abrupt replacement in a shakeup that saw a councilman resign in protest. A letter to the editor of a local paper hailed Smith as “a gentleman of honesty, fairness and high-class.”58 Smith then returned to Reidsville as captain of the prison guards. Less than a year later, he died suddenly at home of a heart attack.

A New York Times obituary remembered Smith for his classic 1916 World Series loss and as “a mainstay of Manager Wilbert Robinson’s mound corps.”59 He was posthumously inducted into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 1980. A state historical marker erected in his hometown in 1994 now memorializes him as MANSFIELD’S FAMOUS SOUTHPAW.60

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Len Levin and fact-checked by Bill Johnson.

Sources

Besides the sources listed in the Notes, the author consulted Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com. Newspaper sources for minor-league data not found in Baseball-Reference.com are cited in the Notes.

Notes

1 Jerry Grillo, “Sherrod Smith Was a Hard Luck Pitcher,” Madison (Georgia) Madisonian, May 17, 1990.

2 Roger Simmons, “Time Out,” Madison Madisonian, January 9, 1948.

3 “Left the Cellar,” Greensboro News, May 15, 1910.

4 “Smith Stingy to Tourist Players,” Tampa Tribune, August 19, 1910.

5 “Twenty-three Men Are in Pirate Fold,” Pittsburg Press, February 3, 1911.

6 “Baseball Notes,” Pittsburg Press, March 10, 1911.

7 “Little Bits of Baseball,” Pittsburg Press, May 12, 1911.

8 Bal’s Baseball Biffs, Pittsburgh Post, May 12, 1911.

9 Edward F. Balinger, “Awful Drubbing Given Pirates by Quakers,” Pittsburgh Post, May 12, 1911.

10 A.E. Cratty, “Pittsburg Points,” Sporting Life, June 17, 1911.

11 “Millers Get New Pitcher,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 1, 1911.

12 Smith’s record with the Millers compiled from Minneapolis Tribune game coverage, June 6 through July 1, 1911.

13 “Sharrod [sic] Smith Is Released,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 2, 1911. The Tribune consistently misspelled Smith’s first name during his stint with the Millers.

14 Springfield (Ohio) Sun, quoted in “Pitcher Smith Is Not Stogie,” Wheeling Intelligencer, July 10, 1912.

15 “Much Depends on Tiger Youngsters,” Newark Evening Star, April 21, 1914.

16 Frank Graham, The Brooklyn Dodgers: An Informal History (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2002), 45. Author Graham has Smith pitching for Springfield against Grand Rapids when Pfeffer persuades the scout to sign the southpaw as well as himself. Such a game would have occurred in 1912, however, not in 1913 when they were teammates.

17 “Sutton Says That Smith Is Iron-armed Southpaw,” Newark Star, January 8, 1914.

18 “Sherrod Smith Working Hard to Earn Tiger Job,” Newark Evening Star, March 13, 1914.

19 “Sherrod Smith Has a Right to Use ‘Hard Luck’ Alibi,” Newark Evening Star, June 10, 1914.

20 “Pitcher Sherrod Smith’s Record,” January 1915, Sherrod Malone Smith Player File, National Baseball Hall of Fame.

21 Bradley Morgan, “Sherrod Smith, Mansfield Star, Has a Birthday,” Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1917.

22 Jimmy Jones, “Sherry Smith Recalls Great Duel with Ruth,” Atlanta Constitution, March 2, 1935.

23 Jerry Grillo, “The Amazing Life and Times of Sherrod Smith,” Madison Madisonian, May 17, 1990.

24 Babe Ruth and Bob Considine, The Babe Ruth Story (New York: Scholastic Book Service, 1963), 38.

25 “Boston Victor Over Brooklyn in 14th, 2 to 1,” New York Sun, October 10, 1916.

26 “Red Sox Triumph After Fourteen Frames of Play,” Omaha Bee, October 10, 1916.

27 Grantland Rice, “World Series Habit Clings to Red Sox,” New York Tribune, October 10, 1916.

28 T.H. Murnane, “Count Is 2 to 1 at Braves Field,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1916.

29 Wallace Goldsmith, “Sparking Moments in a Game Jam-full of Baseball Gems,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1916.

30 Frank O’Neill, “‘Dodgers’ Mistakes Aid Red Sox to Win’ — Robbie,” New York Tribune, October 10, 1916.

31 “Crack Big League Battery Working for Uncle Sam,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 11, 1918.

32 Abe Yager, “Pitcher Sherrod Smith Is Due to Arrive in Boston Today,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 10, 1919.

33 Jack Remington, “Sherrod Smith, Former Dodger, Beaten in France,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 30, 1918.

34 “Football Popular in Y.M.C.A. Camps,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 24, 1918.

35 “YD Regulars Beat Yans, 5-4,” Boston Post, April 16, 1919.

36 Grantland Rice, “The Sportlight,” New York Tribune, May 10, 1919.

37 “Blame Result on Army Life,” Chicago Eagle, December 20, 1919.

38 In Memory: “Sara Anderson,” Macon (Georgia) Telegraph, March 24, 2016.

39 Grantland Rice, “Three Dodgers Join Mates in Baseball Hall of Fame,” New York Tribune, October 8, 1920.

40 “Dodgers Take the Third, 2-1; Lead in Series,” New York Herald, October 8, 1920.

41 Grantland Rice, “Former Brooklyn Pitcher Shuts Out Old Mates with Three Hits,” New York Tribune, October 12, 1920.

42 Henry P. Edwards, “Victory Today Gives Tribe Title,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 12, 1920.

43 Thomas S. Rice, “Departure of Smith to Cleveland Much Regretted,” Brooklyn Eagle, September 19, 1922.

44 Simmons, “Time Out.” Johnson actually pitched nine innings, with reliever Firpo Marberry taking the loss in the twelfth inning, 7-6.

45 Grillo, “Amazing Life.”

46 Henry P. Edwards, “Indians Give Sherry Smith His Unconditional Release,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 5, 1928.

47 Ben Cothran, “A Cracker a Day,” Atlanta Constitution, March 12, 1928.

48 Thad Taylor, “Some Crackers,” Atlanta Constitution, April 15, 1928.

49 Dick Hawkins, “Crackers Lose Final to ’Nooga, 3-0; Game Called in Sixth,” Atlanta Constitution, May 20, 1928.

50 “Pitcher Drives in Winning Run to Beat Braves,” Anniston (Alabama) Star, June 11, 1930.

51 Carl Weimer, “Sherry Smith to Manage Greenville Spinners,” Greenville (South Carolina) News, May 31, 1931.

52 Carl Weimer, “The Morning After,” Greenville News, July 24, 1931.

53 “The Palmetto League,” editorial, Greenville News, July 25, 1931.

54 “Wealthy Hurler Will Play Here,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel, May 16, 1912.

55 Jimmy Jones, “Greatest Lefthanders Now Close to Atlanta,” Atlanta Constitution, March 13, 1932.

56 Jack Troy, “All in the Game,” Atlanta Constitution, September 20, 1943.

57 Bill Jago Jr., “Letter to the Editor,” Madison (Georgia) Madisonian, March 23, 1989.

58 (Signed) A Taxpayer of Madison, “Letter to the Editor,” Madison (Georgia) Morgan County News, November 5, 1948.

59 “Sherrod M. Smith, Once Dodger Star,” New York Times, September 14, 1949.

60 Historical Marker Database, https://hmdb.org/m.asp?m=12260.

Full Name

Sherrod Malone Smith

Born

February 18, 1891 at Monticello, GA (USA)

Died

September 12, 1949 at Reidsville, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.