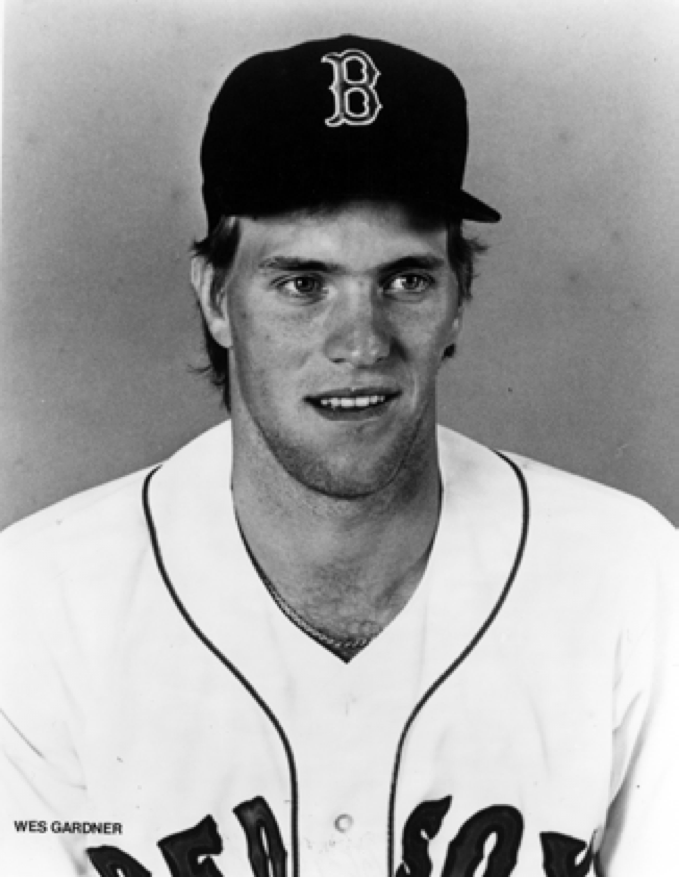

Wes Gardner

The score stood at 11-1 when Tim Lollar left the mound and Wes Gardner took over in the seventh inning in the sixth game of the season at Chicago. With Boston’s comfortable lead, Gardner could relax a little for this, his first game in a Red Sox uniform and his debut in the American League. The team’s lack of early-season luck was reflected in the 2-3 record they now held before this Sunday-afternoon game on April 13, 1986.

First up against Gardner, shortstop Ozzie Guillen hit a triple to center. Outfielder John Cangelosi struck out; Wayne Tolleson hit a sacrifice fly to right – Guillen scored – and Bobby Bonilla, pinch-hitting for Reid Nichols, popped a fly to shortstop Ed Romero. One run, one hit, none left. The lead still secure, the Red Sox went on to win 12-2, and returned to Boston no better or worse than at the beginning of the season. What Gardner did not know then was that the box score that day would tell all about him for the 1986 season:

1986 G W L ERA IP H R SO

1 0 0 9.00 1 1 1 1

Gardner left after the seventh inning with a sore shoulder. At the home opener the next day, he looked forward to his first encounter with the Boston fans. He noticed a “cloud of doom.”1 “It seems to be a sore spot on this team. There’s been so much emphasis on it, but we’ve only played six ballgames. If I can do what Wes Gardner can do, the Boston fans will have a lot to cheer about,”2 He soon found out that there was as much for him to learn about the Boston fans as the fans needed to learn about him. “I have to think I’m the best individual for the job,” said Gardner. “Pitching in the opener would make it more fun. I want to do that. It’s more fun when all the marbles are on the table.”3 Two days later, he was placed on the disabled list with what team physician Arthur Pappas described as “a muscle separation in his throwing shoulder.”4

Wesley Brian Gardner was born in Benton, Arkansas, on April 29, 1961. He never said much about his childhood other than that he had it rough. His life before baseball was not a part of conversations with teammates or others who asked. He steered conversations away from the subject, and in the lengthy interview for this biography, he expressed simply that baseball provided the happiest years of all. His life before baseball is a story only he can relate. His entrance into major-league baseball began in the 22nd round of the 1982 draft, a promising right-handed pitcher out of the University of Central Arkansas. He compiled 20 saves in 40 games with the 1984 Tidewater Tides. He tied for the league lead with 18 saves in 1985 and was named International League Fireman of the Year. But the Mets had a lot of relief pitchers.

Gardner made his major-league debut with the Mets on July 29, 1984, and he stuck with the team the rest of the season, working in 21 games of relief with a 1-1 record and a 6.39 ERA.

Gardner credited Mets minor-league pitching coach John Cumberland with teaching him the no-windup delivery and helping him perfect the split-finger fastball, which he intended to use as a change of pace off his slider and regular fastball.5 He had been a reliever since 1983, but had occasionally worked as a starting pitcher, posting a 3-6 record and 3.71 ERA for the Little Falls Mets in 1982. He also recorded six saves, reflecting his ability in challenging situations, and the Mets sent him to the Instructional League to work on improving as a reliever.

Coming to the Red Sox, Gardner had just 105 days of major-league experience, but he did not lack confidence, another quality the team could use. “I want the ball every day,” he told a Boston sportswriter. “I have pitched as many as 14 days in a row. It doesn’t matter if I have good stuff or bad stuff. I’ll go out there and do what I can do.”6 And Gardner realized, “I just wasn’t going to get the opportunity (with the Mets) that I will get (with the Red Sox), especially with Jesse Orosco and Doug Sisk ahead of me. They had two or three years on me and had done very well.”7 Gardner looked durable, a quality that attracted the Red Sox along with his compact, smooth, no-windup delivery and his split-fingered fastball.

Gardner arrived in Boston along with Calvin Schiraldi, John Christensen, and a minor-leaguer as part of a trade that sent Bobby Ojeda and three minor leaguers to the Mets. Red Sox general manager Lou Gorman, who was in the Mets organization when Gardner and Schiraldi were signed, said, “We see Gardner as a stopper out of the bullpen. We feel he’s the guy to come in in the eighth or ninth and get the last four or five hitters out. He’s going to be an impact pitcher.”8

Gardner first saw Fenway Park in December 1985. “It kind of reminded me of Wrigley Field a little,” he said. Gardner wore uniform number 44. His first-year salary in Boston was $70,000. He was confident. “I look at it with the idea that if anybody can do it, I can. I’ve never had any problems. And I pitch more effectively the more times I have the ball. I have a hard time if I sit five or six days at once.”9

That sore shoulder in his Red Sox debut was something new. “Nothing like this has ever happened to me and it’s very upsetting.”10 One inning, a sore shoulder, 15 days on the disabled list on April 16, and a roster replacement marked the beginning of Gardner’s baseball experience in Boston. He now contributed to the woeful outcome of the Sox-Mets trade. Three of the players the Red Sox acquired in the trade – Schiraldi, Christensen, and Tarver – were biding their time in Pawtucket. Despite his misfortune Wes had spent one inning more in a Red Sox uniform than they had so far. “It’s about to kill my soul that I can’t pitch right now,” Gardner said after being placed on the DL. “It’s hard to come to the ballpark, do exercises and know you’re not going to pitch the rest of the day. And that’s what I’ve got to look forward to for the next 15 days. What’s done is done.”11

Dr. Pappas blamed the slight muscle separation on pitching batting practice in the bitter cold at Tiger Stadium. Rest and exercise were prescribed and after a one-inning rehab stint Gardner felt better but the next day it swelled up again. “I can’t get on top of the ball and throw a breaking ball. When I do, it bleeds and swells up,” he said.12 With replacements lining up, with little improvement from rest and exercise, and despite another good day of throwing batting practice, once he was completely healthy he’d likely return to the bullpen. But then the Sox would have a roster problem, and to relieve that, considered sending Gardner to Pawtucket for a 20-day rehab program until the dilemma was sorted out. All Gardner got from all of that was more uncertainty. “He simply needs to get in the time on the mound and pitch,” said one Red Sox official.13 On July 2, 1986, the Red Sox announced that Gardner, still on the disabled list, was lost for the rest of the season. He underwent arthroscopic surgery to repair the damage.

What did he do the rest of the season and during the World Series with Boston playing against the team he once was a part of? “I didn’t leave Boston. I was at Fenway every day, shagging balls in the outfield, throwing some batting practice. As much as they’d let me. It was a great time, even if I couldn’t pitch a game. We kept winning because we had fun.”14 Gardner gave credit to John McNamara, praising him as the best manager he ever had, because McNamara didn’t give up on him.

Gardner felt ready to get back to pitching when spring training began in February 1987. As Kevin Paul Dupont of the Boston Globe reported from Winter Haven in March, “Gardner’s slow return has progressed this spring at glacial speed. After six outings he owned the highest ERA on the staff (10.13) and without a decision in six appearances.”15 The post-surgery phase had been frustrating. “I thought after the surgery, ‘Heck, they’ll poke two holes in the shoulder and in a couple of weeks I’ll be good.’ Well, in a couple of weeks I was doin’ good just to lift up my arm.”16

At least the pain was gone, but now Gardner struggled with control. He was convinced that the only way he could improve was to just keep throwing. He that he had been hit hard, and had been wild. These days, in his mind, he was throwing “underneath the ball.”17 He wanted one of the five relief jobs, and apparently only Wes Gardner – and John McNamara – thought there was still hope, while sportswriters predicted nothing more for him than a Triple-A club.

To all the beat writers who had Gardner banished to the minor leagues searching for control of his slider, fastball, and splitter, he answered their grim assessment in a game against the Texas Rangers on April 15, 1987. Larry Whiteside, in a poetic tribute wrote, “On a lazy day in April, he rose like the ghost of Dick Radatz. His name is Wes Gardner, and he hardly had been an imposing figure. But yesterday he brought the Fenway faithful to their feet with a dazzling exhibition of speed and confidence.”18 With help from Dwight Evans’s sixth-inning grand slam, the score stood at 5-4 when Gardner came in during the seventh inning to preserve the precarious lead. What Bruce Hurst had left on the bases for Gardner to contend with – runners on second and third and nobody out – gave pause to the Fenway crowd of 16,870. The rest was up to Gardner, and he most definitely was up to the challenge. He struck out the side with 14 pitches, protected a one-run lead “as if it were the Royal Crown of England.”19 Gardner’s spring-training record was still a concern, but in this 40-pitch, 28-strike performance, the concern could be set aside for now. Gardner struck out two more in the eighth, another two in the ninth, and brought the howling crowd to their feet in celebration of a memorable performance that raised the Red Sox to the .500 level with their third straight victory. Lou Gorman, who drafted Gardner for the Mets in 1982 and sent him to the minor leagues to develop as a relief pitcher. Gorman, general manager of the Red Sox in 1984, was still impressed by Gardner’s pitching, saying, “That’s the Wes Gardner I knew when he was in the Mets organization.”20 The skeptics still wondered if Gardner’s performance was just a fluke.

In July Gardner went 8⅓ innings in a relief appearance against the California Angels and six days later was handed his first major-league start in a game in Toronto. “The long relief and that start gave me the chance to face guys over and over. It reminded me, I think, that you have to keep the ball over the plate. Sitting for a year, the way I did, maybe I forgot that.”21 As Kevin Paul Dupont of the Globe believed, the Red Sox had kept Gardner for no other reason than that they couldn’t turn to anyone else. “I didn’t have consistency. I’d pitch well in one game, then awful in the next. I had highs and lows. What I finally decided was to start over, I told myself to forget all the numbers, to just throw ’em away because there weren’t any worth saving, anyway. That’s the way I went for the rest of the year. I told myself to relax.”22

By August 1987 he had made 60 major-league appearances without recording a victory since August 5, 1984, in a Mets game in Pittsburgh. On August 15, 1987, in a game against the Texas Rangers at Fenway Park, Gardner was handed the ball in the seventh inning with his 1987 record of 0-5 in 33 appearances hanging on his back. This time he held the Rangers off, allowing the Red Sox to eke out a lead and hold it for the win. Somewhere between the mound and the clubhouse, someone asked Gardner the obvious question: “Hey, Wes. Did you get the ball?”

“What would I want the ball for?” he said.23 What might have been a better memento for Gardner’s first victory in a Red Sox uniform, wrote Dupont, would have been a picture of the final out of the game. With runners at first and second and Larry Parrish at the plate, Gardner turned around and threw the ball to Marty Barrett who picked Jerry Browne off second base for the final out. With a dramatic gesture and a well-timed toss, he finished off his second career victory flashing an “out!” sign as Mary Barrett raised his glove in celebration. “A straight daylight play,” said Gardner, with a little daylight back in his life.24

Training for the 1988 season began on January 1, when Wes recruited Rich Gedman to help him work on pitching. “We went to Fenway Park. Never missed a day. Then we came down here [Winter Haven] and kept working.”25 He followed Roger Clemens’s exercise regimen, ran two miles farther than Clemens did, and was able to throw freely and loosely, better than he had been able to do in two years. With all that was going on during spring training, no one was paying much attention to Gardner. But Leigh Montville noticed that Gardner, very quietly, had pitched 10 closeout innings allowing only one run, and very quietly, struck out nine batters. There had been a grand hoopla about all the things Lee Smith was doing, but very quietly, Wes Gardner was developing into the closer others thought Smith was going to be. John McNamara pointed out that he couldn’t realistically use Smith as closer in every game, that there was enough room in the bullpen for another.

On June 28, 1988, Gardner made his first start of the year and the second of his major-league career when he was pressed into service after Jeff Sellers suffered a broken hand.

Gardner remembered that day, in an interview in 2011: “John McNamara said, ‘I’ve got to have a starter, and he came up to me one night and said I’m going to start you in a ballgame. I just want you to go as far as you can go.’”26 Giving up one run and three hits in seven innings and striking out four, Gardner won 6-1 in his 99th appearance in the major leagues, and he lowered his ERA to 1.49.

At the All-Star break the Sox were nine games out of first place, but Gardner seemed to be writing a new chapter in his pitching career. Then everything changed. Red Sox president John Harrington had warned that John McNamara would be fired if the team was not in the pennant race by Memorial Day. Despite the recent encouraging turnaround, McNamara was out, and third-base coach Joe Morgan was in. Gardner spent the All-Star break back home in Benton and didn’t know about the firing. When he arrived in Boston a few days later, he found a message on his answering machine. “He said, ‘Have the clubhouse guys put all of my stuff out of my office into your truck and bring it by here when you come home. ‘Uh-huh, they did it,’ he said.”27

Disappointed by McNamara’s firing, Gardner recalled that the manager had always treated him fairly, and credited the ex-skipper for his recent winning streak. “We won because we had fun,” he said, and he didn’t appreciate the way the firing was handled. He found Mac easy to talk to and was comfortable with his different approach to the game.28 We already knew where Mac stood and what he expected out of each and every one of us. We didn’t know how Joe (Morgan) was going to be because he had never been a manager before. He made some guys mad to start with and after everybody got on the same page, we started playing. He was all right.”29

At first, Morgan was named the interim manager until it was clear that under his direction the Red Sox made an immediate turnaround, giving birth to the term “Morgan Magic.” The team won its first 12 games and 19 of 20 under his management. The bullpen endured a rash of injuries, affording Gardner more time on the mound, and by August, though normally utilized as a reliever, he made his seventh start. Paul Harber of the Boston Globe asked him if he wanted to return to the bullpen. “I’d rather not answer that,” said Gardner.30 After enduring three hard-luck losses in August, on September 6 Gardner pitched the first complete game of his career to lead the Red Sox to a 6-1 victory over the Baltimore Orioles, throwing 130 pitches, giving up one run in nine innings to put Boston two games ahead of Detroit as the Red Sox held on to the division lead until the end of the season.

Morgan Magic did not transport the Red Sox deep into the postseason. On October 9 the Oakland Athletics completed a four-game sweep of the ALCS with Dennis Eckersley saving all four games for the A’s. Gardner pitched in relief of Mike Boddicker in Game Three, the only playoff appearance of his career. Gardner had come into the game with two outs in the bottom of the third inning after Ron Hassey hit a two-run homer that put the Athletics up 6-5. He gave up three runs, six hits, and two walks while striking out eight. Bob Stanley replaced Gardner in the eighth inning, gave up another run, and Boston went down to defeat, 10-6.

Despite the rough start to the 1988 season, the fistfights, scandals, a manager fired, the adjustments to a new leader, the antics on and off the field, more than 25 years later Wes Gardner recalled, “1988 was a fun year, and 1989, too. We just couldn’t get past Oakland. Don Baylor used to say we were the only team that could hit four singles and score only one run, so we had to hit home runs or doubles. … We had a chemistry and we all got along.”31 Despite the negative publicity that haunted the 1988 team, something had to click, Gardner said, in order for the team to have gone to the ALCS.

On January 16, 1989, Gardner filed for salary arbitration and then signed for one year at $285,000, more than double his 1988 salary of $117,000. With the departure of Bruce Hurst, it seemed Gardner was set to assume a full-time starting role, as he had been a starter in 18 of his 36 appearances in 1988. Pitching coach Bill Fischer was cautious, saying, “I like his stuff. He’s got a good fastball and better-than-average control. He’s been working with a forkball, and that has helped him. But one of the things we’re going to talk about this spring is coming up with a curveball. If you throw everything hard like he does, the hitter has a pretty good idea of what to look for the second or third time he faces a pitcher. He’s going to have to work on that.”32

On March 4, 1989, Gardner threw his first curveball since he pitched at the University of Central Arkansas where, he recalled, the ball went foul into the seats. He decided then to leave it out of his pitching repertoire. His father had discouraged throwing curveballs until Wes was older than 18, concerned about damage it might do to his arm. Besides the crash course in curves, Gardner, as the Red Sox player representative, was involved with the threatened 1990 strike. He figured he had more time to devote to the job, since he was a starting pitcher. “While everybody else is fishing, I’ll be working on this.”33 Rich Gedman, whom Gardner succeeded, said he felt no pressure from management while he was the player representative and didn’t think his place on the roster was in jeopardy: “If I‘m still around after all that’s happened the last three years, it can’t be true.”34 One week later, the Red Sox reportedly talked with the Kansas City Royals about a possible deal that would bring Danny Tartabull and Floyd Bannister to Boston for Wade Boggs and Gardner.35

There was confidence that Gardner could contribute significantly in 1989 now that he was a full-time starter and had made some adjustments to his fastball and breaking ball while adding a curve. But he didn’t pitch well in his first 1989 start, against Kansas City; his velocity was down and his control was off. He redeemed himself in 3⅓ innings of relief against Cleveland. At the end of April he would turn 28, and he was learning valuable lessons: Nothing comes easy, and a starting pitcher is constantly adjusting.36

By early May elbow soreness returned and worsened. Joe Morgan had predicted that Gardner would be a significant part of the bullpen, but so far his pitching had been a concern: He exhibited brief flashes of success and future promise, then was neutralized by problems with control and inconsistency. Steve Fainaru of the Boston Globe wrote that when he was ahead in the count, Gardner could be devastating, that he could throw a slider, the key to his success, while setting up his fastball.37 He had won just 12 games since he came to the Red Sox, and he had been on and off the disabled list, pitching in relief, as a closer, and now a starter. He was the player representative, had endured trade rumors, and earned a modicum of fame for his handsome features that appeared in magazines as well as that popular clothing advertisement on the wall of the Copley T station.

The rift grew wider between Morgan and Gardner, who learned about his removal from the rotation by way of the media, not from Morgan himself. Morgan complained about Gardner’s inconsistency, about the poor performance in 1⅓ innings against Oakland on May 20, when he was removed from the game by Morgan and tossed the ball to Joe Price instead of handing it to Morgan. The manager acknowledged that Gardner was a victim of bad luck but that he also had nothing good – no breaking ball, no slider, only his fastball was effective and that wouldn’t last long. Morgan added to Gardner’s frustration when he publicly mused that he couldn’t understand how a guy “pitching professionally for a long time … ought to know how to make things happen.”38

Neither the relationship with Morgan, the curveball, the day-to-day pitching rotation, his private life, nor the right elbow were working well for Gardner, and a July 17 game in Texas was no help. With two outs and runners on second and third in the first inning, he was ordered to walk Julio Franco, the American League RBI leader at the time, and he then pitched a fastball to the slumping Pete Incaviglia, who proceeded to hit a grand slam. Said Gardner afterward, “I take full responsibility for everything that happened tonight. If I don’t give up two home runs, we win the ballgame. Incaviglia hit a homer off me and if you check the books, you’ll see it was his first hit off me. I just threw him a bad pitch.” “We got trounced,” said Joe Morgan.39

On August 27 Gardner collapsed on the mound after he was struck by Mike Brumley’s smash in the fifth inning of the Red Sox win over Detroit and suffered a fractured cheekbone that put him on the 21-day disabled list. The hit was the first time his head had met with a batted ball, and the injury cut short a frustrating and painful season.

On April 12, 1990, in the third inning in Detroit, Gardner walked off the mound to the disabled list when his right elbow again failed him. According to Dr. Arthur Pappas, Gardner’s injury was common to pitchers who threw sliders. Steve Fainaru of the Globe mused, “One has to wonder what will become of Gardner, a fixture in Boston despite a long run of mediocrity. The team’s player representative, he will turn 29 on April 29. He has a 14-19 record with the Red Sox and a 4.75 ERA. This is the fifth time on the disabled list, leading him to mutter an expletive yesterday while croaking, ‘So what’s new?’ when talking about his elbow.”40

As he was coming back from the latest DL stint, rumors circulated that the Red Sox were interested in working out a trade, offering Gardner and Marty Barrett to the Kansas City Royals, “to deal either or both for a humble return.”41 Trade talks all year long would become the bane of Gardner’s existence, not that he hadn’t seen the writing on the wall. But he hoped for the best. Gardner recalled that though the Boston fans were great, sometimes the writers were not. He remembered that the curly red-haired one often irritated him, and recalled the tall blond sports reporter who waited patiently outside the Fenway Park clubhouse door, politely asking for some comments from him – words he returned as cordially as she had asked of him. While some of those writers were beginning to write his pitching obituary, Gardner carried on, pitching a good game alternating with another disaster. Morgan pulled him out of a 1-0 game in the sixth inning on June 10, 1990, conceding that he was “very good,” that he had pitched a nice game, but he had given up three walks and they all scored, didn’t they? (Only two of them scored.) The game was Gardner’s first start since August 27, 1989, the one in which he had been injured by Mike Brumley’s hit to his face.

“Everybody would like to be Roger and win 20 games. But certain people have to fill a role and pick up the slack here and there. I got on a roll in 1988 and I’d like to get on another one of those rolls. And I think I will, sooner or later, if they don’t give up on me.”42 But the 1990 season was the best of times and the worst of times for Wes Gardner. A great game here, a blowout there, no run support, a start, a short relief, a perfect game spoiled in the fifth inning, stints on the disabled list. “I just have buzzard’s luck,” said Gardner. “What can I do?”43

The Red Sox somehow found a way to win the division title on the last day of the season and again faced the Athletics, who had swept them in the 1988 ALCS. Gardner was cut from the postseason roster. He declined when invited to travel with the team. The Athletics repeated that four-game postseason sweep. Trade talks heated up as Boston looked to improve the bullpen and considered the available free agents and many promising young players. Gardner was on the auction block, although previous offers had not been successful and he hadn’t gathered much interest as a reliever. Lou Gorman declined to comment on the possibility that Gardner might be released, hoping he might be at least useful for that once sought-after “humble return.” On December 15 the deal was made. Gardner was traded to San Diego for two minor-league prospects, outfielder Steve Hendricks and pitcher Brad Hoyer. Boston also acquired the high-priced Astros free agent Danny Darwin, who was next to wear Red Sox number 44. Gardner left Boston behind, declared “a bust” by Boston Globe writers Peter Gammons and Nick Cafardo.44

1990 G W L ERA IP H R SO

34 3 7 4.89 77.1 77 43 58

When Gardner landed in San Diego in 1991, several former teammates were already there. Calvin Schiraldi had arrived the year before at what became a refugee camp for Red Sox players who also included Bruce Hurst, Marty Barrett, and Tony Torchia, once a Red Sox coach who had a lawsuit pending against his former employer. Gardner avoided placing blame for his problems on Boston’s management of him or the team. He thought most of his problems stemmed from an abundance of talent that led to being shuffled from relief to closer to starter. “I feel good about being over here,” Gardner said. “At least I know what my role is going to be.”45 But the sore right elbow continued to cause trouble. He pitched in relief in 14 games with San Diego before being handed his unconditional release on May 31. He was picked up by Kansas City but pitched in only three games for the Royals and spent most of his time with their Omaha affiliate.

A telephone interview with Gardner was a 2½-hour riot through baseball anecdotes, nostalgia, reflections on life as a pitcher, and life after the career he had that was filled with fun, challenges, and the inevitable regret of a retired major-league pitcher. He recalled that Boston had been trying to improve the bullpen, and he was part of a project that would give him more opportunity to pitch. He didn’t care if he was a starter, closer, or reliever, the position he thought he was best suited for. “I like the challenge of coming in for a tight situation and trying to get out of it,” he said. “You gotta have a thick skin for that stuff. I didn’t only come in a game a reliever, I did sometimes start – and close a few times. Rich Gedman caught me a lot.”

Gardner’s pleasant memories of playing in Boston, he said, have never faded. “Tony Peña! What a great guy! He caught me the last two years I was in Boston. He knew how to get me going and calm me down. I remember one time Tony walked out to the mound when I was having a bad time of it, and he said: ‘Wes, now or never, ball up.’ Great memories,” he laughed. “It was a great time for me.”46

Leaving baseball behind was difficult. Back in Benton, Arkansas, he was far from a major-league team to watch up close. He enjoyed watching young players coming up like Torii Hunter, Travis Wood, and Bo Jackson. He especially was interested in the second talented pitcher to graduate from Benton High School, Cliff Lee, who has accomplished much that he admires.

In 2001, Gardner was inducted into the University of Central Arkansas Bears Hall of Fame. Beyond baseball, he worked as a master electrician, lived with his family in his hometown, but still thought back about his years playing baseball. Former catcher Ed Hearn, a teammate of Gardner’s on the Mets who kept in touch with him, said he thought Gardner had the perfect mentality as a reliever, and that he still has a big heart, one that remains full of baseball.47 After all that he experienced in Boston, one might presume Gardner would be contrite about the time spent with the Red Sox, that he might have wished he’d been somewhere else, but he said, “If I went back to baseball now, I’d go back there. My heart is in Boston.”48

Notes

1 Dan Shaughnessy, “The Opening Act Is a Show,” Boston Globe, April 14, 1986: 33.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Larry Whiteside, “Gardner Placed on Disabled List,” Boston Globe, April 17, 1986: 55.

5 Ibid.

6 Larry Whiteside, “Gardner Longs for Short Relief,” Boston Globe, February 27, 1986.

7 Ibid.

8 “Sox Acquire Schiraldi, Gardner,” Boston Herald, November 14, 1985.

9 Ibid.

10 Whiteside, “Gardner Placed on Disabled List.”

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Larry Whiteside, “KC’s Park is a Royal Pain,” Boston Globe, April 25, 1986: 45.

14 Ibid.

15 Kevin Paul Dupont, “Gardner Is Trying to Get Back in Control,” Boston Globe, March 28, 1987: 25.

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 Larry Whiteside, “Gardner Gives Sox Shot in Arm, 5-4,” Boston Globe, April 16, 1987: 35.

19 Ibid.

20 Associated Press, “Gardner’s Relief, Evans’ Grand Shot Floors Texas,” Paris (Texas) News, April 16, 1987: 15.

21 Kevin Paul Dupont, “His Sun Shines – At Last Three Years After the First One, Gardner Notches Another Win,” Boston Globe, August 16, 1987: 58.

22 Leigh Montville, “Relief At Last Gardner Finds Belated Success,” Boston Globe, March 31, 1988: 33.

23 Kevin Paul Dupont, “His Sun Shines.”

24 Ibid.

25 Leigh Montville, “Relief At Last – Gardner Finds Belated Success.”

26 Tony Lenahan, “Former Major League Pitcher Wes Gardner Talks Baseball, Playoffs,” Saline Courier, Saline County, Arkansas, December 16, 2011.

27 Ibid.

28 Telephone conversation with Wes Gardner, May 1, 2015.

29 Lenahan, “Former Major League Pitcher Wes Gardner Talks Baseball, Playoffs.”

30 Paul Harber, “Gardner Refused to Give the Rangers a Break,” Boston Globe, August 3, 1988: 25.

31 Lenahan, “Former Major League Pitcher Wes Gardner Talks Baseball, Playoffs.”

32 Larry Whiteside, “Gardner Signs One-Year Pact,” Boston Globe, January 19, 1989: 55.

33 Dan Shaughnessy, “Gardner Takes Over As Player Rep,” Boston Globe, March 21, 1989: 83.

34 Ibid.

35 Jim Brown, “The Clipboard,” Macon (Missouri) Chronicle-Herald, March 28, 1989: 2.

36 Larry Whiteside, “Sox Show Confidence in Gardner,” Boston Globe, April 17, 1989: 37.

37 Steve Fainaru, “Still On Hold Injuries, Lapses Stalling Gardner,” Boston Globe, May 13, 1989.

38 Steve Fainaru, “Demotion Irks Gardner,” Boston Globe, May 21, 1986: 21.

39 “Rangers Rout Red Sox, 12-6,” Kerrville (Texas) Times, July 18, 1989: 9.

40 Steve Fainaru, “Pitching Staff Shows Signs of Deep Trouble,” Boston Globe, April 13, 1990: 73.

41 Nick Cafardo, “No Takers on These Two, Gorman Unsuccessful in Dealing Gardner, Barrett,” Boston Globe, May 15, 1990: 68.

42 Dan Shaughnessy, “Gardner Remains Confident That His Luck Will Change,” Boston Globe, June 11, 1990: 41.

43 Nick Cafardo, “Red Sox Keep Skidding on the Road,” Boston Globe, July 7, 1990: 29.

44 John Snyder, Red Sox Journal (Cincinnati: Emmis Books, 2006), 567.

45 Larry Whiteside, “The San Diego Red Sox,” Boston Globe, March 19, 1991.

46 Ibid.

47 Telephone conversation with Ed Hearn, April 26, 2015.

48 Telephone conversation with Wes Gardner, May 1, 2015.

Full Name

Wesley Brian Gardner

Born

April 29, 1961 at Benton, AR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.