New York Metropolitans team ownership history, 1883-1887

This article was written by Bill Lamb

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

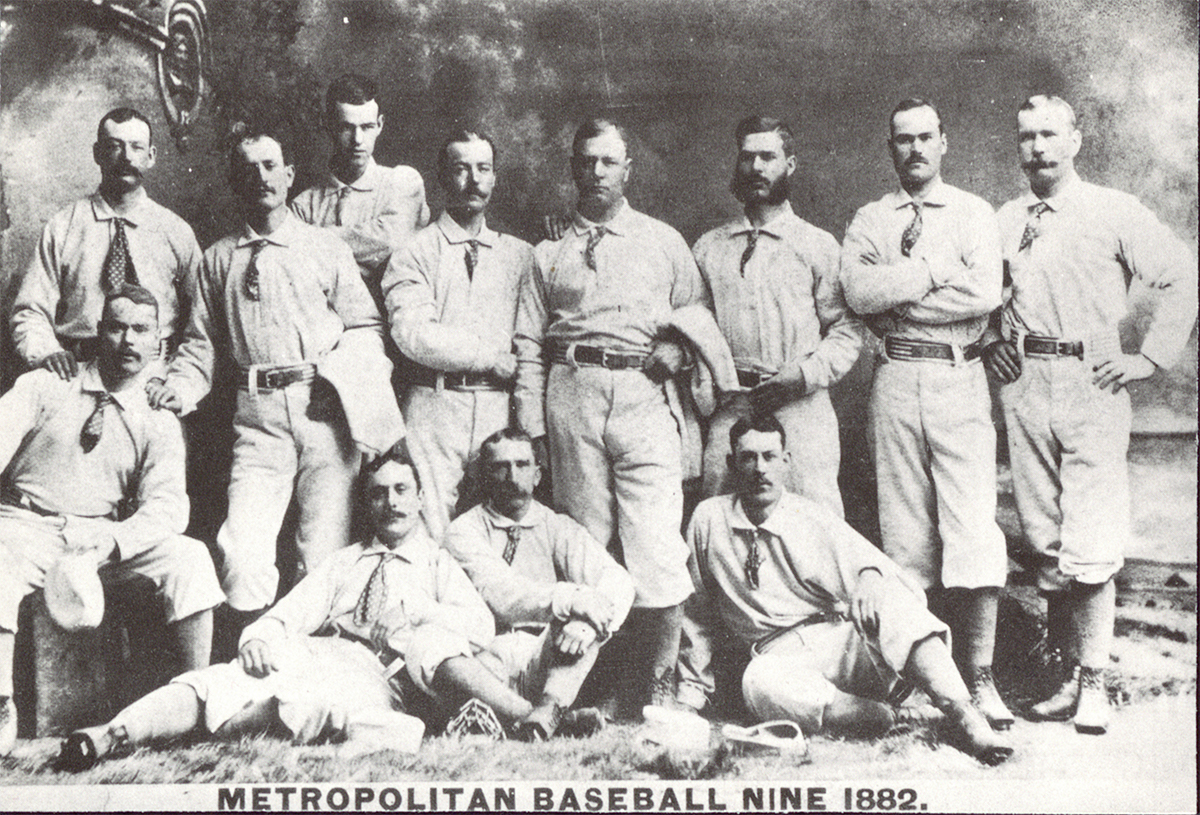

The 1882 New York Metropolitans were a strong independent professional club, winning 101 games against top competition, before joining the upstart American Association as a major-league team in 1883. (SABR-Rucker Archive)

On May 8, 1961, the name of the National League’s newest expansion club was officially announced. The fledgling team was to be called the New York Mets.1 Principal club owner Joan Payson revealed that the Mets nickname was selected from 644 candidates placed in nomination by New York baseball fans and other participants in the naming process.2 Some news reports on the new club’s moniker also mentioned, in passing, that a late nineteenth-century major-league team had been called the New York Metropolitans.3

Semi-furnishing a nickname was not the only trail blazed by the nascent club’s long-ago predecessor. In September 1880 the transfer of its games from Brooklyn to north Manhattan made the Metropolitan Base Ball Club the first professional nine that could legitimately call New York City home. Prior thereto, the National League New York Mutuals and other clubs effecting the New York name had been based in Brooklyn, then a municipality separate and distinct from New York City and the third largest city in the nation.4

In 1883 the New York Mets (as the team was popularly known) attained elite status, entering the major-league American Association. The Mets quickly achieved success on the playing field, capturing the AA pennant in 1884 – the first championship of a major league ever won by a New York team. Yet only three seasons later, the club was disbanded. In the paragraphs below, this essay will endeavor to recall the five-season life of the nineteenth-century Mets through focusing on its ownership history.

The Formation and Independent Years

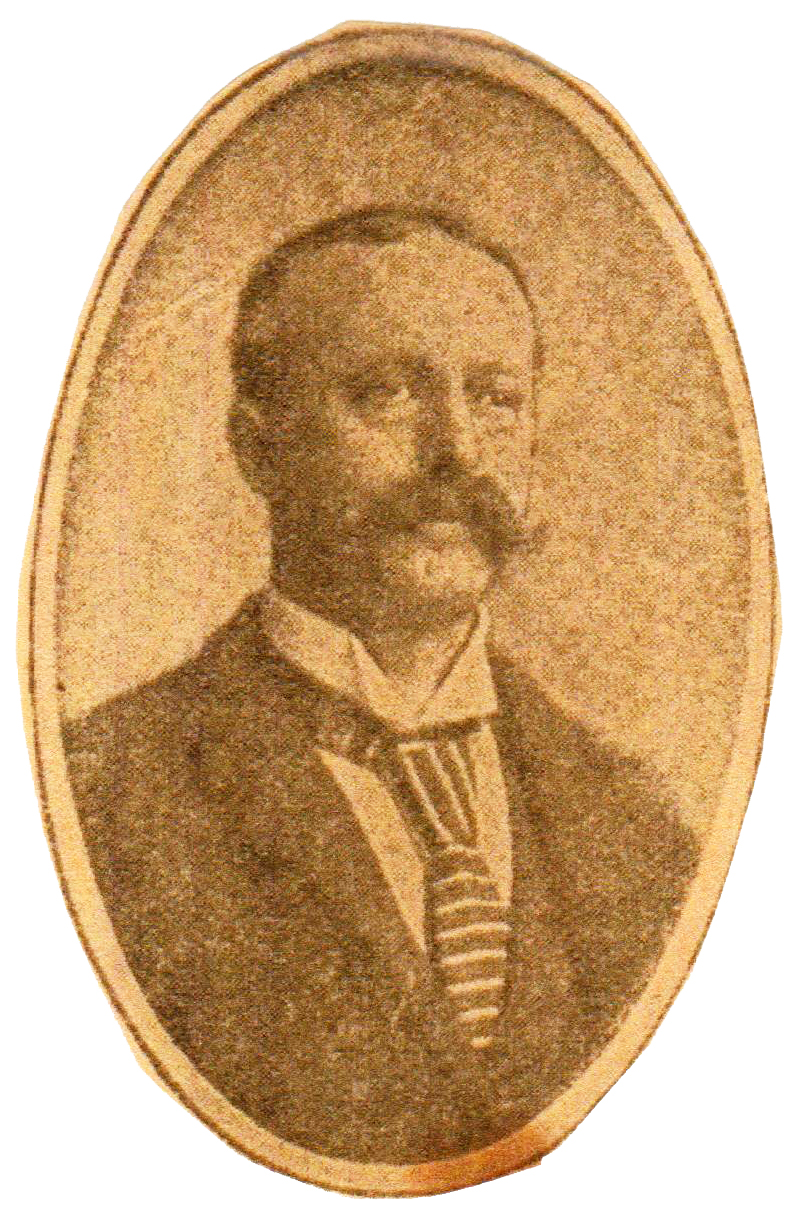

The founder of the original Mets, and of professional baseball in New York City, was John B. Day, a prosperous cigar manufacturer originally from Connecticut and an amateur baseball enthusiast. In the late 1870s, Day relocated to Manhattan to oversee operation of a newly opened tobacco processing plant on the Lower East Side. Only in his early 30s, Day was still young enough to play ball and devoted much of his leisure time to pitching for local amateur clubs.

The founder of the original Mets, and of professional baseball in New York City, was John B. Day, a prosperous cigar manufacturer originally from Connecticut and an amateur baseball enthusiast. In the late 1870s, Day relocated to Manhattan to oversee operation of a newly opened tobacco processing plant on the Lower East Side. Only in his early 30s, Day was still young enough to play ball and devoted much of his leisure time to pitching for local amateur clubs.

The transformation of Day from weekend hurler to professional baseball club owner stems from an encounter with Jim Mutrie during the summer of 1880. Mutrie, a marginally gifted minor-league shortstop but a man with organizational skills and a keen judge of playing ability, was then between engagements and killing time in Manhattan.

Two versions of the Day-Mutrie encounter endure. According to lore, Mutrie introduced himself to Day after watching the cigar magnate’s servings get pounded by opposition batsmen in nearby Orange, New Jersey.5 But according to the venerable Henry Chadwick, the Day-Mutrie meeting was arranged by New York sportswriters.6 Whichever the case, Mutrie had a proposition for Day. If the well-heeled capitalist would finance the venture, Mutrie would recruit, sign, and manage a professional baseball team that would play under Day auspices.

Intrigued, Day agreed, and soon Mutrie was busy stocking the roster of the new side – formally named the Metropolitan Base Ball Club – with first-rate talent, much of it coming from the Unions of Brooklyn and the recently disbanded Rochester Hop-Bitters.

On September 15, 1880, the newly organized Mets made a successful debut, thrashing the depleted Unions 13-0 on the home field of the Brooklyn club.7 At the time, the absence of suitable playing sites in heavily built-up Manhattan dictated that local professional teams, even those adopting the name New York, play their games in Brooklyn or elsewhere. But Day was determined to change that and to have his club play in Manhattan. A probably apocryphal tale has a Midtown bootblack tipping off Day to the availability of a grassy meadowland situated just north of Central Park at Fifth Avenue and 110th Street.8 Occasionally used by the Manhattan Polo Association but mostly vacant, the grounds were flat and dry, featured seating for several thousand spectators, and were already partially enclosed by fencing. Once a lease for use of the premises was obtained from property owner James Gordon Bennett Jr., the socialite-sportsman who published the New York Herald, Day relocated his ballclub to New York City proper.

On September 29 the Mets inaugurated their new home field at the “Polo Grounds” with a 4-2 win over the Nationals of Washington,9 the contest being played before an eye-catching crowd of 2,000 to 3,000 paying customers.10 Years later, club owner Day revealed that the late arrival of the Nationals had been cause for grave concern, the prospect of seeing the Mets play a hastily gathered pickup nine instead of the advertised opposition generating unrest among the crowd until the Nationals finally showed up.11 By the time that its brief first season ended, the Mets had compiled a creditable 16-7-1 log, which included a 12-3 victory over Manhattan College in which Day himself pitched a complete game.12

Smitten by baseball club ownership, Day quickly envisioned bigger things for the Mets. To underwrite his ambitions for the team, Day incorporated the Metropolitan Exhibition Company (MEC), with himself as president and dominant shareholder. Recruited as minority-stake investors were Walter S. Appleton and Charles T. Dillingham, both in the Manhattan bookselling trade and ardent baseball fans.13 Over the winter, additional grandstands were erected behind a home plate placed in the southeast quadrant of the property. Meanwhile, other alterations needed to convert the grounds from polo to baseball use were completed.

The Mets had held their own against National League opponents during their abbreviated late-1880 run, winning a respectable one of every three games played.14 Nevertheless, Day declined overtures to place his ballclub in the NL for the 1881 season.15 Rather, the Mets would play a taxing, self-created 151-game schedule, mixing contests with teams affiliated with the League Alliance and Eastern Championship Association amid those against local independent, semipro, and college nines.16 And again the Mets would have National League opponents on the docket.

Day’s decision to keep the Mets independent rather than join the NL is not as perplexing as it may seem to modern observers. Although an avid baseball buff, Day was also a clear-eyed businessman who expected to make a profit from his investment in the pro game. The National League, bereft of franchises in the nation’s three largest cities (New York, Philadelphia, and Brooklyn), was far from a surefire moneymaker in 1881. And traveling to distant venues like Chicago, Detroit, and Cleveland twice a season was an expensive proposition – with no guarantee of covering costs from game receipts. Indeed, the refusal of the Brooklyn-based New York Mutuals and Philadelphia Athletics to go on money-losing late-season road trips had prompted their expulsion from the NL only five years before.

The Mets’ fall 1880 run had demonstrated that money could be made outside the game’s “major league.” Keeping the Mets independent also allowed Day to craft the club’s playing schedule to his liking; confine travel to road trips likely to be profitable; and avoid payment of the admission fee, league dues, and other assessments attendant to joining the National League. And the independent New York Mets could still play a host of games against NL opposition – on dates and at places mutually agreeable to club boss Day and his NL counterpart.

Managed by Jim Mutrie and with a lineup that included past or future major leaguers Dude Esterbrook, Steve Brady, Ed Kennedy, and Chief Roseman, the 1881 Mets captured the Eastern Championship Association title handily, finishing 10½ games better than the Athletics of Philadelphia.17 The ECA crown was the first professional baseball championship of any kind garnered by a New York club. The Metropolitans also continued their respectable showings in head-to-head matches against the game’s top-echelon clubs, winning 18 of 59 games played against National League teams during the 1881 season.18

Such performance made the Mets an attractive prospect to those intent on forming a rival major league for the following season. On November 2, 1881, manager Mutrie and Metropolitan Exhibition Company minority stockholder Walter Appleton represented the Mets at the American Association’s organizational meeting in Cincinnati. But acting on Day’s instructions, the pair declined to commit their club to the fledgling circuit.19 Days later, they informed National League President William Hulbert of the decision to keep the Mets out of the AA – at least for the time being.20 But Day also declined another invitation to place the Mets in the National League.21

Entry into the American Association

The Mets remained an independent professional club in 1882, again playing major-league (National League and American Association) competition tough while running roughshod over ECA clubs and other nines on the way to posting an overall 101-58-3 (.635) record and taking another ECA title.22 After the season, MEC boss Day confounded expectations by again declining an invitation to place the Mets in the National League. Instead, the Mets accepted membership in the upstart American Association for the 1883 season. Likely in gratitude, MEC junior partner Appleton, nominally New York Metropolitans club president, was appointed to the American Association board of directors at the circuit’s annual meeting that November. Simultaneously, Mets manager Mutrie was tabbed for the AA schedule committee.23

Later that offseason, John B. Day unveiled his master plan. In addition to putting the Mets in the AA, Day was intent on placement of an entirely different MEC ballclub in the National League. The necessary vacancy in league ranks was promptly created by the jettisoning of the NL’s weakling franchise in Troy (while Worcester was axed to accommodate Philadelphia’s entry into the league). Troy also furnished the player nucleus – Buck Ewing, Roger Connor, Mickey Welch, and Patrick Gillespie – of New York’s new NL club. Lesser lights on the Troy roster were assigned to the Mets.24

That the NL team, soon to be known as the Giants,25 was the MEC’s favored club was reflected not only in the allocation of playing talent, but also by Day’s appointing himself club president. Also signaling the Mets’ second-class status with the MEC brain trust was dispatch of the Mets to the inferior landfill-based diamond with separate grandstand newly constructed on the southwest quadrant of the Polo Grounds. The premier southeast diamond was reserved for the Giants. The customer base targeted for the two clubs was also stratified. The upper-crust clientele desired by the NL Giants would have to pay 50 cents for general admission. The working-class fans of the AA Mets would get to see games for half that price.

Notwithstanding the attitude of management, the roster of the 1883 New York Mets was far from barren. The right-handed pitching tandem of Tim Keefe and Jack Lynch was promising, while major-league veterans Candy Nelson (shortstop), Steve Brady (first base), Bill Holbert (catcher), and John O’Rourke (outfield), plus rookie Dude Esterbrook (third base) provided respectable lineup material. And the retention of Jim Mutrie at the managing helm added stability to the club mix. But preseason exhibition game play between the two MEC teams indicated that the Giants (with Cooperstown-bound John Montgomery Ward having joined future Hall of Famers Ewing, Connor, and Welch) were the stronger nine. The corporation’s National League club topped the Mets in seven of eight intramural contests.26 The Mets also stumbled out of the regular-season gate, committing 13 errors behind Keefe in their major-league debut, an 11-inning, 4-3 loss to Baltimore played before a turn-away crowd of more than 5,000 at Orioles Park.27 A day later, Lynch hurled the Mets into the win column with a 2-1 triumph over the Orioles.

On May 12, the club returned to New York and dropped a sloppily played (10 errors) 11-4 home opener to the Philadelphia Athletics before some 3,000 Polo Grounds spectators.28 Soon thereafter, MEC brass confronted the spatial problems attending simultaneously-played Giants and Mets home games. The inelegant solution: erection of a temporary canvas fence to separate the outfields of the Polo Grounds diamonds. This meant that on long fly balls, outfielders might have to hop the fence, going from one league’s playing ground to that of another. Including Decoration Day (May 30) doubleheaders, the two New York clubs played at the Polo Grounds at the same time on 12 occasions that season.29

The Mets’ performance improved as the season progressed and, behind the pitching of Keefe (41-27) and the batting of Nelson (.305), the club finished the campaign with a 54-42-1 (.562) mark, good for fourth place in final AA standings. Home-game attendance, however, was a disappointment. Only 50,000 patrons paid their way through the southwest Polo Grounds turnstiles to see the Mets play.30 The Polo Grounds attendance of the Giants (75,000 at twice the general admission ticket price) further cemented the NL club as the MEC favorite, even if the Giants’ 46-50-2 (.479) sixth-place finish was unsatisfactory.

During the campaign, Mets club President Appleton denied reports that the club was to be disbanded at season’s end. “The club has been successful, financially, this year,” Appleton declared. “And whether it wins the pennant or not, it will represent New York in the American Association of 1884. The management has not entertained so much as a thought of its discontinuance.”31 In October Appleton and manager Mutrie repeated that assurance, adding that the Mets would be playing on new grounds the next season.32

Unease about MEC ownership of franchises in both major leagues surfaced at the AA winter meeting. League secretary Jimmy Williams was instructed to notify the Metropolitans that they must cut loose from their National League connection or forfeit membership in the American Association.”33 Mets President Appleton was also removed from the AA board of directors.34 Meanwhile, the MEC commenced construction of a new ballpark for the Mets in Upper East Side Manhattan along the Harlem River. Situated between 107th and 109th streets on a site that had previously been a garbage dump, the unoriginally named Metropolitan Park was a conventionally sized ballpark surrounded by 14-foot-high walls, capable of accommodating 10,000 patrons (but would never have occasion to do so).35

Shortly before the 1884 season commenced, “the Metropolitan Exhibition Company announced the disposal of all their right, title, and interest in the Metropolitan baseball club.”36 Ostensibly the new club owner was the Metropolitan Base Ball Company, incorporated by wealthy Manhattan furniture dealer Frank Rhoner, Mets manager Jim Mutrie, and one W.H. Kipp. The organization was capitalized at $25,000,37 with 175 of the 250 shares issued by the new company held by Rhoner. Mutrie and Kipp divided the remainder. Rhoner also assumed the Mets club presidency.38 It was further announced that “the Metropolitan Exhibition Company has no further connection with the Metropolitan Base Ball Club and will push the interests of the New York club” instead.39 Few baseball insiders, however, were taken in. The ownership transfer was dismissed as a sham designed only to pay lip service to the complaints of other AA club owners about the influence of New York Giants boss John B. Day over Mets’ operations. Incoming New York Mets club President Rhoner was viewed as merely another Day factotum.40

The Championship Season

Back on field, the Mets began the 1884 season in grand style. Before an estimated crowd of 4,000 to 4,500 for the home opener at Metropolitan Park, the Mets breezed to a 13-4 victory over the Pittsburgh Alleghenies.41 The win augured Mets dominance at their new ballpark. But everyone – Mets players, sporting press, baseball fans – hated the place. Sitting amid gas works, manufacturing plants, and slum housing, Metropolitan Park was an uninviting destination. Worse yet, the ballpark was often encased in haze and smoke emanating from nearby factory smokestacks. Fans largely avoided “The Dump,” with home game crowds often measured in the hundreds. Those whose attendance was compulsory did so at purported risk to their health. Resident club wit Jack Lynch was said to have observed that infielders at Metropolitan Park “could go down for a grounder and come up with malaria.”42

Despite their disdain of Metropolitan Park, the Mets had won 20 of 26 games played there by the time the team left home for an extended road trip on June 19. While the team was away, the MEC decided to pull the plug on Metropolitan Park. When the Mets returned, their home games were shifted to the Polo Grounds. Metropolitan Park was used only when a Mets home playing date conflicted with a Giants home game.43

Regardless of where they called home, the New York Mets were the class of the American Association that season. Paced by the yeoman hurling of Keefe (37-17) and Lynch (37-15),44 the batting of burly young Dave Orr (a league-leading .354 BA with 112 RBIs) and Dude Esterbrook (.314), and the generalship of manager Jim Mutrie, the Mets posted a sterling 75-32-5 (.701) record and cruised to the American Association championship. In the years to come, the New York Giants, New York Yankees, and twentieth-century New York Mets would win 61 major-league pennants. But the honor of being the very first Gotham club to win such a title belongs to the 1884 New York Metropolitans. The Metropolitans’ bubble was burst, however, when matched against the National League champion Providence Grays in a three-game postseason precursor of the modern World Series. Behind the pitching of 60-game winner Hoss Radbourn, Providence swept the series via lopsided, poorly attended victories, all recorded at the Polo Grounds.45

The Ensuing Decline

Notwithstanding the postseason disappointment, a New York City parade was held in the Mets’ honor. But things were not so cheery back at MEC headquarters. Even with a pennant winner, the Mets drew only 68,000 home fans and posted a $15,000 loss for the season.46 The MEC’s other ballclub presented the reverse situation. The talent-laden Giants had done no better than tied for fourth in National League final standings, but had drawn 105,000 patrons to the Polo Grounds47 and returned a $35,000 profit for the company.48 Corrective action was therefore privately formulated by John B. Day. In the meantime, the appearance of normalcy was retained with figurehead Mets President Rhoner and manager Mutrie attending the winter meeting of the American Association in December.49 But belying the publicly proclaimed divorce of the MEC from operation of the Metropolitans, MEC honcho Day, plus corporate sidekicks Walter Appleton and Charles T. Dillingham, also put in an appearance at the AA conclave.50

The design to bolster the Giants at Mets expense first manifested itself with the offseason reassignment of Mutrie to the helm of the company’s National League club. Some rule-bending chicanery was thereafter deployed to spirit away Tim Keefe and Dude Esterbrook. New contracts were not extended to the Mets stars, making them available for signing by other AA clubs. But during the 10-day contract signing window, Keefe and Esterbrook were incommunicado, reportedly vacationing with Mutrie at John B. Day’s onion farm in Bermuda.51 Other reports had the trio sunning themselves in Cuba.52 Wherever they had gone, by the time Keefe and Esterbrook returned home they were newly-engaged members of the New York Giants.53

When news of the Keefe and Esterbrook defections broke, American Association club owners howled in protest. At a hastily called circuit meeting, Mutrie was expelled from the AA54 (an empty gesture, given that Mutrie was now employed by a National League club). The Association also imposed a $500 fine on the Mets.55 The sanction, in turn, was denounced as “highway robbery” by Mets club President Frank Rhoner,56 but events exposed his irrelevance to operation of the franchise. Only days before the Keefe-Esterbrook move was publicly revealed, Rhoner stated that “he knows no facts of a deal between the New Yorks and the Metropolitans for the transfer of Keefe and Esterbrook.”57 In an embarrassed huff, Rhoner resigned his position as club president. This prompted an unidentified Sporting Life commentator to remark: “Did anyone ever charge or suppose for a moment that Rhoner ever knew anything of these matters? How quickly, though … he washed his hands of the whole thing when he found out what little account he was.”58

Acquiring Rhoner’s paper interest in the franchise was Joseph Gordon, a prosperous Manhattan coal dealer and Tammany Hall insider.59 Gordon, once a standout pitcher as a city schoolboy, would become an important adviser to MEC boss Day and go on to have a long association with major-league baseball in New York.60 For the time being, he immediately assumed the post of New York Metropolitans club president,61 while incoming team manager Jim Gifford took Mutrie’s place on the Mets board of directors.62

Under new skipper Gifford, the wounded and demoralized 1885 Mets club plummeted to seventh place in the AA standings. Although Dave Orr (.342 BA, with 56 extra-base hits and a league-leading .543 slugging average), Candy Nelson, Steve Brady, and Chief Roseman still gave the Mets a decent everyday lineup, there was no replacing pitching ace Keefe. In fact, Jack Lynch’s fall-off 23 wins exceeded the total posted by nonentities Ed Cushman (8-14), Doug Crothers (7-11), Ed Bagley (4-9), and Buck Becannon (2-8), combined. At the same time, the addition of Keefe and former Buffalo star Jim O’Rourke brought the count of future Hall of Famers on the Giants roster to six. Thus fortified, the MEC’s favored club skyrocketed to an exceptional 85-27 (.759) record, only to be edged out in the National League pennant chase by the even-better 87-25-1 (.777) Chicago White Stockings.

Sale and Relocation

The reversal in team fortunes, plus the fact that the Giants had outdrawn the Mets by nearly three to one in Polo Grounds attendance, convinced the MEC to concentrate its holdings.63 To that end, the New York Metropolitans were put up for sale. Enter Erastus Wiman, a Canadian-born millionaire businessman-entrepreneur looking to add to the stable of attractions based in his adopted home of Staten Island.64 In early December 1885, Day and Wiman closed a $25,000 deal that transferred complete ownership of the New York Metropolitans to Wiman.65

Wiman’s plan to relocate the ballclub to Staten Island encountered immediate resistance in American Association ranks. To prevent that from happening, circuit magnates voted to expel the Mets from their organization and substitute a club from Washington, DC, in its place. Injunctive relief obtained by Wiman attorneys temporarily stymied that stratagem, while the neophyte club owner blasted the now-stayed AA action. 66 “In all my experience, I have never heard of proceedings so unjustifiable,” an indignant Wiman proclaimed. “Staten Island shall have a baseball club and I already have offers to form a new and stronger association than the one just now guilty of the sharp game reflecting very little credit on baseball ethics.”67 Wiman’s vow to fight was reiterated by recently appointed club secretary George F. Williams, who directly blamed the AA opposition on Brooklyn Grays boss Charles Byrne, fearful of competition from a club situated on nearby Staten Island. Byrne also coveted slugging first baseman Dave Orr and fly hawk Chief Roseman and was reportedly in contract negotiations with both Mets stalwarts.68

Other AA magnates had little appetite for battle with the deep-pocketed Wiman, and the Association soon capitulated. On December 28, 1885, the Wiman-owned New York Metropolitans were recognized as a member club of the American Association.69 And pursuant to the reconciliation process, Byrne was obliged to relinquish any claim that Brooklyn might have had on the services of Orr and Roseman.70

Once his franchise rights were secure, Wiman set about getting his St. George Grounds ready for baseball. The small army of masons, carpenters, and workmen loosed on the site swiftly erected a handsome wooden edifice capable of seating about 4,100 in a two-tiered covered grandstand stationed behind home plate.71 Seated there, spectators were afforded expansive views of New York Bay, the Narrows separating Staten Island and Brooklyn, Sandy Hook, and the cities of New York, Brooklyn, and Jersey City.72 But oddly, the new ballpark contained no seating along the foul lines or beyond the outfield. As an incentive to entice distant customers to St. George Grounds, admission to Mets games included round-trip ferryboat fare to and from Battery Park in Lower Manhattan or Jewell’s Wharf in Brooklyn.73

Given that lightly populated Staten Island was then outside the borders of New York City (and Brooklyn), the Mets were largely ignored by large-circulation metropolitan dailies, prompting one out-of-town journal to observe: “Erastus Wiman ought to buy a [news]paper in his Staten Island resort, so that the club would receive mention when they are at home. The New York papers are inclined to ignore the Mets.”74 It is uncertain, however, how actively club President Wiman involved himself in day-to-day operation of the franchise. His time was mostly devoted to myriad other business interests, particularly an ambitious project to transform sleepy Staten Island into a major commercial port and railroad terminus.75 Administration of routine club affairs was therefore likely the responsibility of managing club director Walter Watrous and/or club secretary Williams. Nevertheless, making the grand gesture that he was fond of, Wiman donated an expensive solid silver trophy to be awarded to the American Association champion at season’s end.76

On April 22, 1886, the New York Metropolitans inaugurated play in their new Staten Island home by dropping a 7-6 decision to the Philadelphia Athletics. “Fully five thousand were in attendance,” noted the New York Herald, but “judging from the inconvenience that they were put to, it is not likely that the crowd will be so large every day.”77 Getting to Staten Island took some effort and only 1,500 showed up at St. George Grounds the next day to see the A’s drub the Mets, 14-6. By late May, Wiman had had enough of his club’s poor play. He discharged holdover field leader Jim Gifford for being “too easy on the boys,” replacing him with crusty veteran Bob Ferguson.78 The managerial change made little difference. The Mets’ 53-82-2 (.393) seventh-place finish duplicated the previous season’s result, while the 67,000 attendance figure at St. George Grounds was about the same as the year before at the Polo Grounds, but spread over 11 more home playing dates.79

Endgame

The Mets got off poorly again in 1887, losing their first 10 games. By late May, the club was solidly ensconced in the American Association cellar. At midseason, Wiman was confirming reports that he might “give up baseball at Staten Island. The ‘Mets’ certainly are not a success,” he lamented.80 Nor did the situation improve thereafter. By the campaign’s end, New York’s dismal 44-89-5 (.331) record fueled its third consecutive seventh-place finish, some 50 games behind the AA champion St. Louis Browns. Shortly thereafter, Wiman divested himself of the New York Metropolitans, selling the ballclub for the same $25,000 that he had paid for it two years earlier.81 Deducting his investment in player salaries and ballpark construction, Wiman’s dalliance with the game reportedly cost him $30,000, if not more.82

The new owners of the New York Mets were Brooklyn club boss Charles Byrne and his partners in the Grays franchise. Brooklyn co-owner Gus Abell assumed the presidency of the Mets while Byrne appointed himself club treasurer.83 Byrne further announced that “the Mets will next season play upon Manhattan Island, and the strongest team the Mets ever placed in the field will represent it next season.”84 But this was all pretense; New York Giants boss John B. Day was never going to consent to a return of the Mets to New York City.85 Nor did Byrne intend to operate a nearby competitor to his Brooklyn club. Rather, the Mets had been acquired so that its playing talent could be absorbed by the Grays. In short order, slugger Dave Orr, pitcher Al Mays, and outfielders Paul Radford and Darby O’Brien were transferred to the Brooklyn roster. The remaining Mets players were released. Byrne then relinquished the playerless New York franchise to the American Association.86 The franchise hulk was subsequently assigned to Kansas City, thereby ending Staten Island’s brief run as a major-league baseball venue and bringing to a close the history of the New York Metropolitans.87

Epilogue: During its five-season stint in the American Association, the New York Metropolitans posted a cumulative 270-309-13 (.464) regular-season record, highlighted by the capture of the 1884 AA pennant. At various times during those years, the club contingent included Hall of Fame pitcher Tim Keefe, formidable batsman Dave Orr, everyday worthies Jack Lynch, Candy Nelson, Paul Radford, and Chief Roseman, and astute field leader Jim Mutrie. The Mets, of course, were hardly the only major-league club not to survive the nineteenth century. But the causes of the franchise’s demise were somewhat unique.

First and foremost, the Mets fell victim to internal decision-making, becoming secondary in the plans of its ownership, the Metropolitan Exhibition Company. Although he had founded and financed the Mets, dominant MEC shareholder John B. Day – whether for reasons of prestige, profit, survivability, or whatever – chose to prefer the National League New York Giants over the Mets when it came to franchise investment, acquisition of playing talent, use of the Polo Grounds, or other advantage. Even the winning of the 1884 American Association crown could not dissuade the MEC from focusing on the Giants. Indeed, immediately thereafter, the Mets were crippled (via the transfer of Mutrie, Keefe, and Esterbrook) to improve the NL club.

This is not to say that Day and his cohorts were wrong. As their respective attendance figures attest, New York baseball fans preferred the Giants over the Mets. Perhaps more important, concentrating MEC attention on just one club proved shrewd business. When the Mets went belly up in 1887, the Giants were on the cusp of back-to-back world championships (in 1888 and 1889) and shattered National League attendance records in the process.88 The Giants were also a cash cow, with one report placing the profits earned by the MEC over the first decade of its existence at $750,000.89 While this figure seems inflated – no MEC club is known to have ever reported a single-season profit in excess of $50,000 – ballclub ownership provided Day and the others with a handsome and reliable income stream, almost all of which flowed from operation of the Giants, not the Mets.

In retrospect, however, the event that sealed the doom of the New York Metropolitans was the club’s acquisition by Erastus Wiman. Like Day and Mets club President Joe Gordon, both one-time amateur players themselves and hard-core baseball enthusiasts, Wiman claimed a pedigree in the game. According to nineteenth-century baseball historian Preston D. Orem, Wiman “was a former baseball catcher and proudly displayed his broken fingers and gnarled hands to prove it.”90 But even if true, Wiman’s stewardship of the Mets strongly suggests that he viewed ownership of a professional baseball club and its relocation as merely a means of extension of his Staten Island amusement empire. Acquisition of the Mets also promised (but did not deliver) increased traffic on Wiman-owned ferryboat and rail lines. But Staten Island, sparsely populated and inconveniently located, was a graveyard for a major-league baseball club. Once the club did not generate the revenues that the commerce-minded Wiman anticipated, he gave up the venture, leaving the Mets’ fate to Brooklyn club boss Charles Byrne. And once he had title to the Mets, Byrne predictably reduced the unwanted rival to nothing but the franchise carcass, which the American Association then assigned to faraway Kansas City.

For the 1896 season, tempestuous Andrew Freedman, a successor to Day as New York Giants club owner, revived the New York Metropolitans name, bestowing it on a short-lived Giants farm club that he placed in the minor Atlantic League.91 Thereafter, the name remained forgotten for well over a half-century, only to be resurrected when the National League decided to place an expansion franchise in New York for the 1962 season. The official names of the two ballclubs – New York Metropolitans vs. New York Mets – are not identical. But that technicality aside, the 1883-1887 American Association club can fairly lay claim to being the original New York Mets.

BILL LAMB spent more than 30 years as a state/county prosecutor in New Jersey. He was the longtime editor of “The Inside Game,” the newsletter of SABR’s Deadball Era Committee, and the author of “Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial and Civil Litigation” (McFarland, 2013).

Acknowledgments

This club history is derived from an essay published in David Krell, ed., The New York Mets in Popular Culture (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2020). Excerpts republished by permission; all rights reserved.

Notes

1 Dick Young, “Our NL Club Christened ‘Mets,’” New York Daily News, May 9, 1961: 42. See also Louis Effrat, “New National League Team Here Approves Mets as Its Official Nickname,” New York Times, May 9, 1961: 48.

2 “Champagne Baptism: N.Y. Names Ball Club ‘Mets,’” San Francisco Examiner, May 9, 1961: 55; “‘Mets’ Is Now Official Name for New York Club,” Harlingen (Texas) Morning Star, May 9, 1961: 5.

3 “‘Mets’ Nickname for NY’s Team,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 9, 1961: 35; “They’ll Call ’Em Mets,” Miami Herald, May 9, 1961: 39.

4 The modern-day five-borough New York City (Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island) did not come into existence until January 1, 1898. During the 1880s, the city consisted only of Manhattan and parts of the West Bronx.

5 Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds: The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 22.

6 Brooklyn Eagle, December 26, 1886: 6. Yet another version had the Day-Mutrie introductions made by a local semipro pitcher named Jimmie Clinton. See “To-Day and Yesterday,” Brooklyn Daily Times, October 20, 1911: 6.

7 “Base Ball,” New York Sun, September 16, 1880: 2, which reported that the “Metropolitans appeared in new uniforms of blue stockings, and white suits trimmed with blue, and they presented a very neat appearance.” See also “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Times, September 16, 1880: 3.

8 Hynd, 23.

9 The Mets added four runs in the top of the sixth, but the score reverted to 4-2 when darkness prevented the Nationals from completing their sixth-inning turn at bat.

10 “Base-Ball on the Polo Grounds,” New York Times, September 30, 1880: 8. The game’s attendance was adjudged “by far the largest assemblage that has gathered on a ball field in this vicinity in three years.”

11 “John B. Day Tells of a Bitter Hour,” New York Times, February 6, 1916: S3.

12 “Metropolitan vs. College Nine,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, October 4, 1880: 2. Also, “Base Ball,” Brooklyn Daily Times, October 4, 1880: 4, which gives the final score as 13-3.

13 Appleton and Dillingham had been acquainted for years but it is unknown whether either man knew Day beforehand. In any event, Mets second baseman-turned-sportswriter Sam Crane later asserted that Appleton and Dillingham had been induced to invest in the MEC by Mets manager Mutrie, rather than by Day. See “A Bit of History,” Sporting Life, February 11, 1893: 3.

14 Richard Hershberger, “Memorable Games: Metropolitans 4, Nationals 2, September 29, 1880” in Stew Thornley, ed., The Polo Grounds: Essays and Memories of New York City’s Historic Ballpark, 1880-1963 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2019): 177.

15 “Base Ball on the Polo Grounds and Elsewhere,” New York Sun, October 10, 1880: 7. The National League had just expelled its Cincinnati club and was in need of a replacement franchise for the 1881 season.

16 The League Alliance was an association of independent professional baseball organizations established by the National League in 1877. By the 1881 season, the League Alliance was mostly dormant, supplanted by the Eastern Championship Association, a similar organization consisting of independent pro clubs from the New York, Philadelphia, and Washington areas.

17 Robert D. Warrington, “Philadelphia in the 1881 Eastern Championship Association,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 48, No. 1, Spring 2019: 83.

18 Woody Eckard, “Henry Chadwick and the National League’s Performance Against ‘Outsiders’: 1876- 1881,” Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 52, No. 2, Fall 2023: 73.

19 David Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League: The Illustrated History of the American Association – Baseball’s Renegade Major League (New York: Lyons & Burford, 1994): 21.

20 “Sporting Events,” Chicago Tribune, November 6, 1881: 7; “Adheres to the Old League,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 7, 1881: 7. Hulbert had ample reason for concern about American Association overtures toward the Mets. New York and Philadelphia, the nation’s two largest cities, had been bereft of a National League team since 1876 when Hulbert orchestrated the expulsion of the New York Mutuals and Philadelphia Athletics from the National League for failure to complete their playing schedules. Placement of an American Association club in either venue would greatly enhance the new circuit’s prestige as well as its chances for survival against the NL.

21 “Baseball Notes,” New York Clipper, December 10, 1881: 615. Day was said to be put off by the National League’s 50-cent general admission mandate.

22 Brooklyn Eagle, December 26, 1886: 6. The Mets posted a 19-45 log against National League opponents and won all but one of six games played against American Association teams in 1882. Another source puts the Mets’ overall record at 101-57-3 (.639). See Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3rd. ed, 2007), 137.

23 Per Cliff Blau’s New York Mets chronology for the American Association project, accessible online via the SABR research collection website. Appleton is also identified as a member of the American Association board of directors in “Miller Reinstated,” Sporting Life, August 13, 1883: 3.

24 In a talent evaluation blunder, future Hall of Fame pitcher Tim Keefe, another Troy refugee, was deemed unworthy of a berth with the MEC’s National League team and consigned to the Mets.

25 In the beginning, the MEC’s NL team was sometimes called the Gothams or Maroons but more often simply as the New-Yorks. The nickname Giants did not gain currency until 1885. For purposes of clarity, however, the club will be called the New York Giants throughout this essay.

26 “Baseball: The New-Yorks Win Seven of Eight Games,” New York Herald, May 1, 1883: 4.

27 “Opened with a Victory,” Baltimore Sun, May 2, 1883: 1.

28 The attendance estimate was published in “Baseball,” New York Truth, May 13, 1883: 6.

29 As calculated from 1883 game-day logs compiled by Retrosheet. The Mets posted an aggregate 4-8-1 (.333) record playing on the southwest Polo Grounds diamond on dates when the Giants were in action on the adjacent southeast field.

30 Robert L. Tiemann, “Major League Attendance,” Total Baseball (Kingston, New York: Total Sports Publishing, 7th ed., 2001), 74. Spread over 46 home playing dates (including doubleheaders), the Mets drew an average of less than 1,100 fans per game date.

31 “The ‘Mets’ All Right,” Sporting Life, August 6, 1883: 3.

32 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, October 1, 1883: 3.

33 Preston D. Orem, Baseball from the Newspaper Accounts, 1882-1891 (Altadena, California: Self-published, 1966-1967): 75, accessed via the SABR research collection website.

34 Blau, Mets chronology. Appleton’s removal coincided with a downsizing of the AA board membership.

35 More on Metropolitan Park can be accessed via http://sabr.org/bioproj/park/metropolitan-park-new-york. The ballpark featured a covered 3,500-seat grandstand and 6,500 bleacher-type seats.

36 Orem, 104. See also, “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 20, 1884: 11; “Gotham Gleanings,” Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1884: 3.

37 “The Base Ball Muddle,” Sporting Life, December 16, 1885: 4.

38 Once Rhoner was installed, former Mets club President Walter Appleton assumed the title of New York Giants vice president and took a seat on the NL club’s board of directors.

39 Orem, 104.

40 “A Base Ball Muddle,” 4.

41 “Metropolitan Park,” Sporting Life, May 21, 1884: 5; “Three Championship Games,” New York Herald, May 14, 1884: 5. The attendance figures included the guested NYC Board of Aldermen and about 1,000 other freeloaders.

42 Nemec, 62.

43 Use of the playing field in the southwest quadrant of the Polo Grounds was discontinued after the 1883 season. Home date conflicts resulted in seven July-August 1884 Mets home games being played at Metropolitan Park.

44 In the season finale, Buck Becannon notched a six-inning complete-game victory for the Mets. This was the only game in which someone other than Keefe or Lynch pitched for New York in 1884.

45 Providence outscored the Mets by an aggregate run count of 21 to 3, including a 12-2 match closer viewed by only 300 Polo Grounds spectators.

46 Orem, 125. The loss included the one-time cost of construction and maintenance of now-abandoned Metropolitan Park. The MEC was also on the hook for the remainder of the five-year real property lease granted by the city.

47 Tiemann, Total Baseball, 74.

48 Orem, 138.

49 “The Annual Meeting,” New York Clipper, December 20, 1884: 634.

50 Blau, Mets chronology.

51 “Base Ball,” Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1885: 5; “Baseball,” New York Herald, April 13, 1885: 6; “Base Ball,” Cleveland Leader, April 10, 1885: 3; and elsewhere.

52 “Diamond Dust,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 4, 1885: 7.

53 “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, April 22, 1885: 6.

54 “The American Association,” Trenton Evening Times, April 30, 1885: 1; “The American Association Meeting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 28, 1885: 8.

55 “Base Ball,” Boston Evening Transcript, April 28, 1885: 2; “The Reserve Rule Dead,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, April 28, 1885: 4. A previous motion to expel the Mets from the AA was considered too drastic and withdrawn.

56 “Sporting Affairs: Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1885: 2.

57 “Still Rampant,” Sporting Life, May 20, 1885: 6.

58 “Harlem Echoes,” Sporting Life, May 27, 1885: 6.

59 “Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 12, 1885: 2. New York Times, May 12, 1885: 3.

60 Among other things, Gordon located the site in far north Manhattan where Day erected the New Polo Grounds in 1889. Gordon would serve as first club president of the American League New York Highlanders in 1903. Some 20 years later, he tried to broker a deal for the sale of the New York Giants to one-time club boss Harry Hempstead.

61 As per the Chicago Tribune and New York Times, May 12, 1885. See also “Notes and Comments,” Sporting Life, May 20, 1885: 7.

62 Orem, 172. What became of third Mets board member W.H. Kipp is unknown.

63 In 1885 the Giants drew 185,000 fans to home games at the Polo Grounds. The Mets attracted only 64,000 to the same ballpark. Tiemann, Total Baseball, 74.

64 In addition to outdoor opera, Wild West shows, theatricals, and other amusements staged at his newly built St. George Grounds, Wiman also owned Staten Island ferryboat and rail lines.

65 “The Metropolitan Club Deal,” New York Clipper, December 12, 1885: 616; “Mr. Wiman’s Baseball Club,” New York Times, December 5, 1885: 8.

66 “Sporting Notes,” Dallas Morning News; “The American Association Restrained,” New Haven (Connecticut) Morning Journal and Courier; “Erastus Wiman’s Baseball Club,” New York Tribune, all published December 11, 1885.

67 “Erastus Wiman Indignant,” New York Times, December 5, 1885: 2.

68 “To Stand by Mr. Wiman,” New York Times, December 13, 1885: 10.

69 “The Association: The Mets Again in Full Membership,” Sporting Life, January 6, 1886: 1; “Mr. Wiman’s Final Victory,” New York Times, December 28, 1885: 1; and elsewhere.

70 “The Mets and Brooklyn,” New York Times, December 30, 1885: 2; “The American Association,” Hartford Daily Courant, December 29, 1885: 3.

71 A thorough treatment of St. George Grounds can be accessed at https://sabr.org/bioproj/park/st-george-grounds.

72 “Hard by the Bay,” New York Times, March 14, 1886: 14.

73 Phillip J. Lowry, Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks (New York: Walker & Company, 2006), 149.

74 “What the Players Are Doing,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, April 11, 1886: 3.

75 For more detail see the Wiman BioProject profile, above. The collapse of the venture would eventually lead to financial ruin for Wiman.

76 The glass-encased trophy was cast in the form of a 26-inch-high batter standing at the plate and valued at between $1,000 and $2,000. For more, see Robert H. Schaefer, “The Wiman Trophy and the Man for Whom It Is Named,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Fall 2007): 44-54.

77 “Batting for Championships,” New York Herald, April 23, 1886: 8.

78 David Nemec and David Ball, “James H. Gifford,” in David Nemec, ed., Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 2 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 123-124.

79 As calculated from Retrosheet data. The 135 games the Mets played in 1886 were 25 more than the previous season but did not include any home doubleheaders.

80 “Mr. Wiman and the Mets,” New York Herald, July 22, 1887: 9.

81 “Byrne Buys the Mets,” Louisville Courier-Journal, October 9, 1887: 4; “The Metropolitans Sold,” New York Times, October 9, 1887: 3; “The Sale of the Mets,” St. Paul Globe, October 9, 1887: 5.

82 Schaefer, above, puts the total Wiman losses at $30,000. But other sources pegged the Mets’ deficit for the 1887 season alone at $26,000. See e.g., “Byrne Buys the Mets.”

83 “Byrne and the Mets,” Chicago Inter Ocean, October 9, 1887: 2; “The Mets Sold,” Leavenworth (Kansas) Times, October 9, 1887: 1.

84 “Byrne Buys the Mets.”

85 Two years earlier, Byrne had been cajoled into waiving enforcement of the National Agreement rule that prohibited the placement of a major-league club within five miles of another club when the Mets moved from north Manhattan to Brooklyn’s doorstep on Staten Island.

86 Nemec, The Beer and Whisky League, 146-147.

87 Early in the 1889 season, the New York Giants, displaced from the original Polo Grounds, played 23 games at St. George Grounds before settling in at the New Polo Grounds in far north Manhattan.

88 The 1889 New York Giants attracted a NL record 305,000 fans to the Polo Grounds. Tiemann, Total Baseball, 74. Interestingly, the AA Brooklyn Bridegrooms (née Grays) drew even better: 353,690.

89 “An Offer for the Giants,” New York Times, September 6, 1889: 3, reporting MEC rejection of a $200,000 bid for the Giants made by Polo Grounds landlord James J. Coogan.

90 Orem, 217.

91 By July, fellow Atlantic League club owners had grown tired of Freedman’s antics and expelled the Mets. Presiding over the expulsion gathering was Atlantic League President Sam Crane, a second baseman for the 1882-1883 New York Metropolitans.