June 3, 1925: Eddie Collins joins the 3,000-hit club

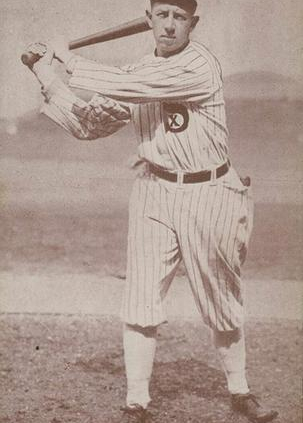

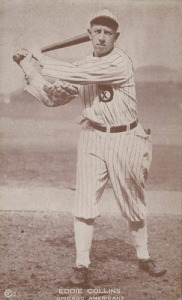

Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939, Eddie Collins is considered one of the best second basemen of all time. Renowned manager John McGraw, whose New York Giants clubs were defeated by Collins’s teams in three World Series, said, “Eddie Collins is the best ballplayer I have seen during my career on the diamond.”1

Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1939, Eddie Collins is considered one of the best second basemen of all time. Renowned manager John McGraw, whose New York Giants clubs were defeated by Collins’s teams in three World Series, said, “Eddie Collins is the best ballplayer I have seen during my career on the diamond.”1

Collins maintained that level of play over a career that spanned from 1906—when he made his major-league debut under an assumed name while still a student at Columbia University—to 1930.2 In 1914, during the Deadball Era, he received the Chalmers Award as American League MVP. Nine seasons later, in 1923, with scoring and home runs up, Collins finished second in the MVP voting to Babe Ruth, then came in second again to Walter Johnson a year later.

“Collins sustained a remarkable level of performance for a remarkably long time. He was past thirty when the lively ball era began, yet he adapted to it and continued to be one of the best players in baseball every year. … [H]is was the most valuable career that any second baseman ever had,” wrote baseball historian Bill James.3

Collins was especially adept at stealing bases. He studied pitchers carefully, especially their feet and hips, and was able to take large leads and get a good jump when trying to swipe a bag.4 He retired with 741 career steals, eighth best all-time as of 2022.

In addition to being a prolific basestealer, Collins was a consistent hitter. In 1920 he batted .372 with 224 hits and finished his career with a .333 batting average. He averaged 178 hits per season for 16 years (1909-1924).

Collins reached the 1,000-hit plateau on August 26, 1913, at 26 years old, in his 832nd career game. It took him another 895 games to get to 2,000 hits, a milestone he attained on his 33rd birthday, May 2, 1920.

By then Collins had moved from the Philadelphia Athletics to the Chicago White Sox. After four American League pennants and three World Series championships in Philadelphia, Connie Mack sold his star second baseman’s contract in 1915 for financial reasons.

Collins won another championship with the White Sox in 1917 and captained the infamous 1919 Black Sox team that threw the World Series. Collins was not in on the fix; his career continued after eight Chicago teammates were banned for life.

The White Sox finished seventh or eighth in the American League three times from 1921 through 1924, but Collins continued to hit. In 1925 he took on a player-manager role and was batting .327 after a three-hit game in a 16-15 loss to the Detroit Tigers on June 2.

Collins’s hits in that slugfest gave him 2,999 for his career, setting him up to reach the 3,000-hit plateau during the final game of the series the next day. The White Sox were in third place, seven games behind the Philadelphia Athletics, with a 23-20 record.

The sixth-place Tigers had a 20-26 mark but had won 11 of their last 14 games, including five of six against Chicago. With a high-powered offense that led the AL in 1925 with 903 runs, Detroit had racked up 70 runs on 112 hits in its last seven games.

Leading the Tigers was baseball’s all-time hit king, 38-year-old manager and center fielder Ty Cobb. Six months older than Collins, Cobb had been a member of the 3,000-Hit Club since August 1921. Like Collins, he also had three hits on June 2, including a walk-off homer in the bottom of the ninth.

The White Sox starter on June 3 was future Hall of Famer Ted Lyons. The 24-year-old right-hander was in his third year with Chicago and possessed a 5-2 record with an excellent 1.93 earned-run average. The Tigers countered with six-year-veteran righty Rip Collins, who had lost his first five decisions in 1925 and had a 2-7 record and a 4.35 ERA.5

Chicago’s Johnny Mostil opened the game with a double. One out later, Eddie Collins came to the plate for his second opportunity at the milestone. (He had walked in the ninth inning the previous day after reaching 2,999 hits in the seventh.)

Collins hit a single to center to become the sixth man in major-league history to attain the 3,000-hit plateau. Mostil scored, and Chicago had a 1-0 lead.

That score held until the top of the third inning. With men on first and second and one out, Collins slapped another RBI single. Earl Sheely followed with a single that made the score 3-0.

After putting two runners on base in each of the first two innings but not scoring, the Tigers got to Lyons in the bottom of the third. A single by Fred Haney and a double by Frank O’Rourke brought Cobb to the plate with men on second and third and one out. Cobb’s groundout scored Detroit’s first run. A single by Harry Heilmann and a double by Lu Blue tallied two more runs for the Tigers, and tied the score, 3-3.

In the top of the fourth inning, shortstop Jackie Tavener’s throwing error allowed Chicago’s leadoff batter, Willie Kamm, to get on. A double by Ray Schalk and a single by Mostil drove in two runs, putting the White Sox back ahead, 5-3. Collins’s third hit of the day gave the White Sox men on the corners, and Mostil stole home on a double steal. Two more hits drove in another couple of runs before Rip Collins could get out of the inning, but the White Sox had scored five times to increase their lead to 8-3.

Lyons had control problems in the bottom of the fifth. He walked the bases loaded, and all three runners scored on a double by Heilmann and a sacrifice fly by Blue. The Tigers now trailed by two.

The Chicago hurler settled down after that inning, allowing the Tigers just one more run, in the bottom of the seventh. The White Sox added four more runs off Rip Collins and the Detroit relief corps to make the final score 12-7 in Chicago’s favor.

The teams combined for 29 hits, which made for a lengthy contest by the standards of the day. The Chicago Tribune reported, “[T]he game dragged so badly that fans were late for supper and lots of others missed the boat to Windsor [Ontario, Canada, across the Detroit River]. The game took 2 hours and 32 minutes.6

Collins played with the White Sox through 1926. His final four seasons returned him to the Athletics. There, his teammates in 1928 included two other members of the 3,000-Hit Club: Tris Speaker (who had reached 3,000 the month before Collins did in 1925) and Cobb, in the final year of each of their careers. The team won 98 games and finished 2½ games behind the New York Yankees.

Author’s Note

As noted, Eddie Collins was the sixth member of baseball’s 3,000-Hit Club, following Cap Anson, Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie, Cobb, and Speaker.

When some of Collins’s predecessors reached the 3,000-hit milestone—or were believed to have reached it—in-game commemorations and newspaper coverage celebrated their accomplishment. This was the case for Wagner and Lajoie in 1914.

Newspaper coverage of Cobb’s 3,000th hit in 1921, however, did not reference the milestone. Instead, no date for Cobb’s entry into the 3,000-Hit Club was recognized until 1958. At that time, Stan Musial was approaching 3,000 hits, and a Detroit newspaper realized that it did not have a record of Cobb’s 3,000th. The newspaper searched Cobb’s career records and identified a date for the milestone.

Similar to Cobb, there is no coverage from 1925 of Collins reaching 3,000 hits, in the June 3 game or any other. Moreover, research for this article did not identify an origin story—as happened with Cobb—for this game eventually being recognized as the occasion of Collins’s milestone.

A search through the Newspapers.com database in October 2022 revealed that the first mention of a date for Collins’s 3,000th hit was in 1974, as Al Kaline approached his 3,000th.7 The given date for Collins’s milestone was June 5, 1925.8 Eighteen years later, when Robin Yount joined the 3,000-Hit Club, coverage identified June 3, 1925, as the date when Collins attained his 3,000th hit.

“It’s certainly possible that not even Eddie was aware of it,” indicated SABR member Rick Huhn in an October 2022 email. Huhn is the author of Eddie Collins: A Baseball Biography, published in 2008. “He was the antithesis of a self-promoter. Thus, even if he was aware that he had reached the milestone it’s unlikely he would have mentioned it to anyone.”

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to John Fredland for his review and input on the first draft of this article. The article was fact-checked by Kevin Larkin and copy-edited by Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, I used Baseball-Reference.com for team, season, and player pages and logs and the box scores and play-by-plays for this game.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/DET/DET192506030.shtml

https://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1925/B06030DET1925.htm

Notes

1 National Baseball Hall of Fame, “Eddie Collins,” https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/collins-eddie (last accessed April 18, 2022).

2 The day before Collins joined the 3,000-Hit Club another Columbia product made a famous appearance. Lou Gehrig replaced Wally Pipp in the Yankees lineup on June 2, 1925. Gehrig did not miss a game until April 30, 1939.

3 Baseball Almanac, “Eddie Collins Quotes,” https://www.baseball-almanac.com/quotes/quoclls.shtml (last accessed April 18, 2022).

4 Paul Mittermeyer, “Eddie Collins,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/eddie-collins/ (last accessed April 18, 2022).

5 Baseball Reference has 4.35 as the ERA while Retrosheet has 4.48.

6 Almost a century later, games of this length are considered short. The quote is from James Crusinberry, “Swatfest Gives Sox 12 to 7 Win Over Ty Cobbs,” Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1925: 20.

7 Jim Hawkins, “Al’s Endurance, Ability Key to 3,000 Hits,” Detroit Free Press, September 19, 1974: 1-D.

8 Hawkins, “Al’s Endurance, Ability Key to 3,000 Hits.”

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 12

Detroit Tigers 7

Navin Field

Detroit, MI

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.